She passed through Fort Worth at least four times during her dozen years on the national stage. And although she kept her hatchet holstered while in Cowtown, her tongue could chop down a drunkard at his knees.

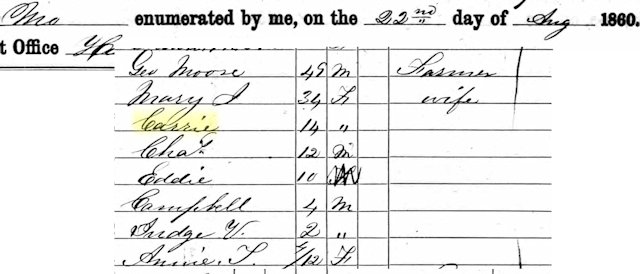

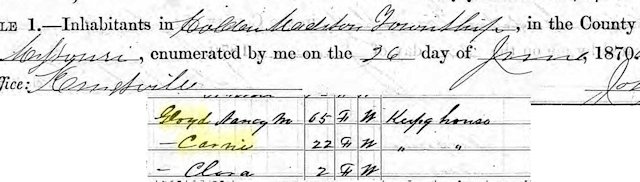

Caroline Amelia Moore was born in Kentucky in 1846. In 1854 her family moved to Belton, Missouri. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Caroline Amelia Moore was born in Kentucky in 1846. In 1854 her family moved to Belton, Missouri. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

In 1867 Caroline married Charles Gloyd, a physician. Their marriage was short but would set the trajectory for Caroline’s life. Gloyd was an alcoholic. Caroline, then known as “Carrie,” became a vehement opponent of alcohol.

In 1867 Caroline married Charles Gloyd, a physician. Their marriage was short but would set the trajectory for Caroline’s life. Gloyd was an alcoholic. Caroline, then known as “Carrie,” became a vehement opponent of alcohol.

In 1874 she married David A. Nation, a newspaperman, attorney, and minister. Nation was nineteen years older than Carrie. They moved to Texas, where David practiced law and Carrie operated a hotel. In 1889 they moved to Medicine Lodge, Kansas, where Carrie founded a branch of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and campaigned for enforcement of Kansas’s law banning the sale of liquor.

In the beginning Carrie’s demonstrations against strong drink were subdued: She would enter a saloon and pray and sing hymns as men drank. But soon she was scolding saloonkeepers with barbed greetings such as “Good morning, destroyer of men’s souls.”

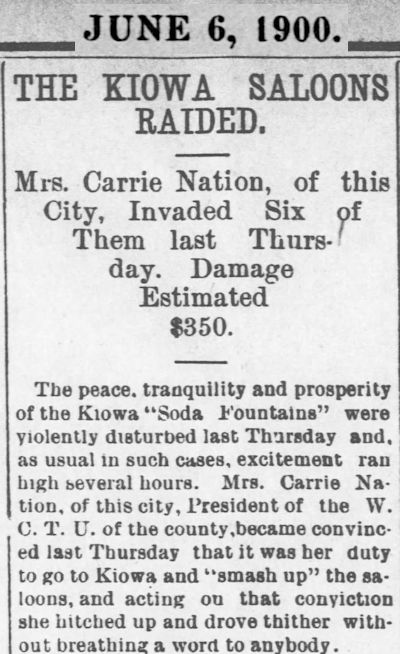

Not satisfied with her results, Carrie prayed for divine direction. On June 5, 1900 she felt she received her answer in the form of a heavenly vision. As Nation later described it:

“. . . I was awakened by a voice which seemed to me speaking in my heart, these words, ‘Go to Kiowa [Kansas],’ and my hands were lifted and thrown down and the words, ‘I’ll stand by you.’ The words ‘Go to Kiowa’ were spoken in a murmuring, musical tone, low and soft, but ‘I’ll stand by you,’ was very clear, positive, and emphatic. I was impressed with a great inspiration, the interpretation was very plain, it was this: ‘Take something in your hands and throw at these places in Kiowa and smash them.’”

Heeding the divine command, Nation gathered up an arsenal of brick bats and rocks—she called them “smashers.”

Heeding the divine command, Nation gathered up an arsenal of brick bats and rocks—she called them “smashers.”

Later that day the customers—all men—in Jasper Dobson’s speakeasy in Kiowa were startled to see a woman walk through the door. She was a large woman, almost six feet tall, weighing 170 pounds. She was dressed somberly. She could have been a church deaconess.

“Men, I have come to save you from a drunkard’s fate.”

With that she took aim and began to throw, breaking bottles, glassware, windows.

She wrecked two more saloons in Kiowa that day.

Soon after, a tornado swept eastern Kansas. Nation interpreted the tornado as divine approval of her raids.

That day in Kiowa and the days that followed put Carrie Nation in the headlines—at first only in Kansas but soon across the country and even in other countries. And she stayed in the headlines for the next twelve years.

Nation’s radicalism had found its inspired MO: Sometimes alone, sometimes accompanied by other female temperance crusaders, she would march into a saloon and sing and pray while smashing anything that would smash. She would be arrested, released on bond, and raid her next saloon. Lather, rinse, repeat.

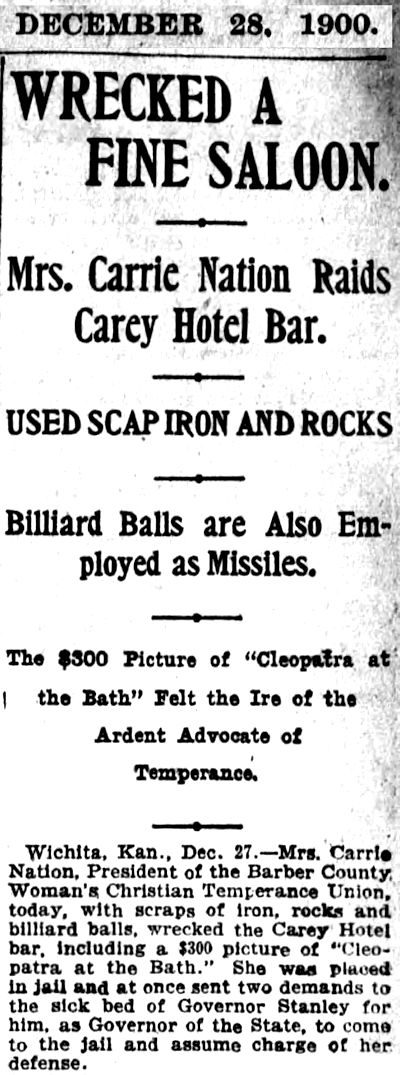

For example, in the bar of the Carey Hotel in Wichita in December 1900 she used scrap iron, rocks, and billiard balls to break glass. She also attacked an immodest depiction of Cleopatra. After Nation was thrown in jail she demanded that the governor get out of his sick bed and come to her legal defense.

For example, in the bar of the Carey Hotel in Wichita in December 1900 she used scrap iron, rocks, and billiard balls to break glass. She also attacked an immodest depiction of Cleopatra. After Nation was thrown in jail she demanded that the governor get out of his sick bed and come to her legal defense.

After the Carey Hotel raid her husband David suggested—in jest—that she should use a hatchet next time for maximum damage.

“That,” Carrie replied, “is the most sensible thing you have said since I married you.”

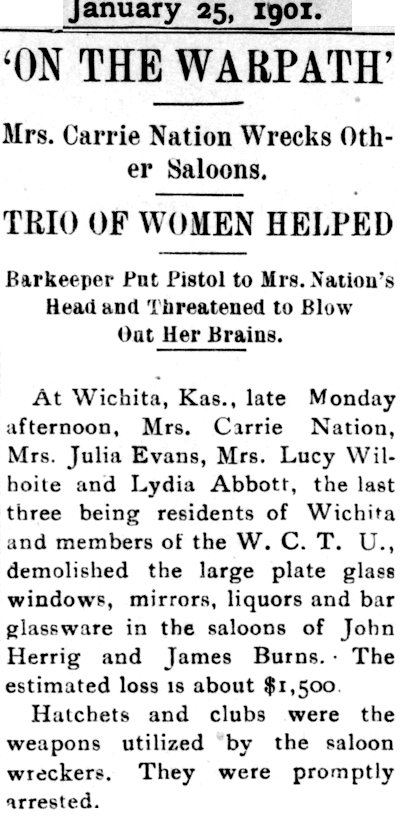

And so it was that on January 22, 1901 Carrie and three disciples did take up their hatchets and make smashy-smashy—windows, bottles, glassware—in two more saloons in Wichita. One saloonkeeper cut his hand on broken glass. Another drew a pistol and threatened to shoot Nation. She was arrested and released on bond. But at the train station the sheriff arrested Carrie before she left town. The sheriff had no warrant. With Carrie was her lawyer: husband David. Carrie asked David if the sheriff had the authority to arrest her without a warrant. David said he thought not.

And so it was that on January 22, 1901 Carrie and three disciples did take up their hatchets and make smashy-smashy—windows, bottles, glassware—in two more saloons in Wichita. One saloonkeeper cut his hand on broken glass. Another drew a pistol and threatened to shoot Nation. She was arrested and released on bond. But at the train station the sheriff arrested Carrie before she left town. The sheriff had no warrant. With Carrie was her lawyer: husband David. Carrie asked David if the sheriff had the authority to arrest her without a warrant. David said he thought not.

So, Carrie slapped the sheriff in the face.

The sheriff turned the other cheek and enlisted bystanders to help him load Carrie into a jail-bound buggy.

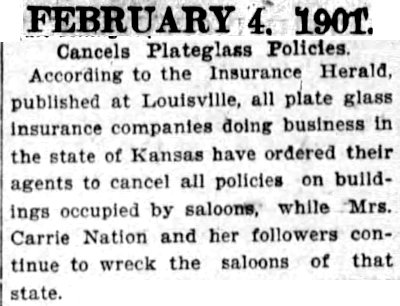

Insurance companies began to cancel policies covering plateglass in saloons as long as Carrie Nation was on a rampage.

Insurance companies began to cancel policies covering plateglass in saloons as long as Carrie Nation was on a rampage.

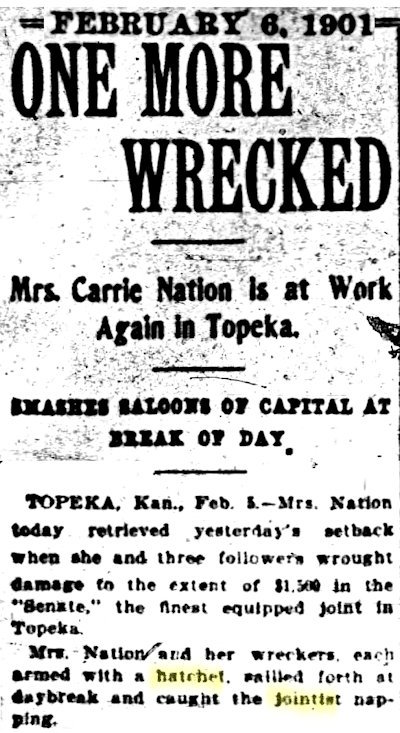

On February 5 Carrie and company, hatchets in hand, raided the Senate Saloon in Topeka at daybreak, catching the “jointist” asleep. (Saloons and speakeasies were called “joints” and their operators “jointists.”)

On February 5 Carrie and company, hatchets in hand, raided the Senate Saloon in Topeka at daybreak, catching the “jointist” asleep. (Saloons and speakeasies were called “joints” and their operators “jointists.”)

Nation began to refer to her saloon raids as “hatchetations.”

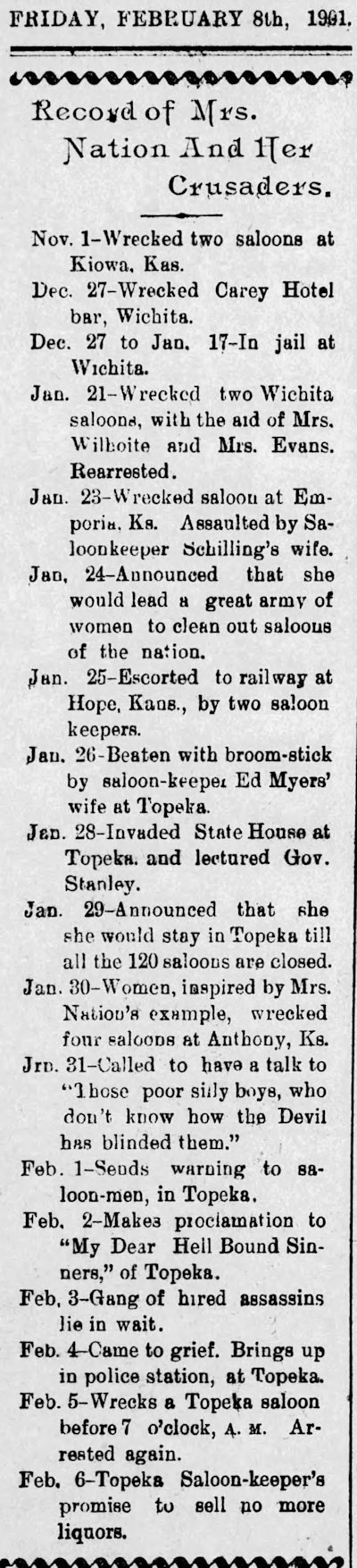

For Carrie Nation the end of 1900 and beginning of 1901 were a whirlwind of raids and arrests and retaliations.

For Carrie Nation the end of 1900 and beginning of 1901 were a whirlwind of raids and arrests and retaliations.

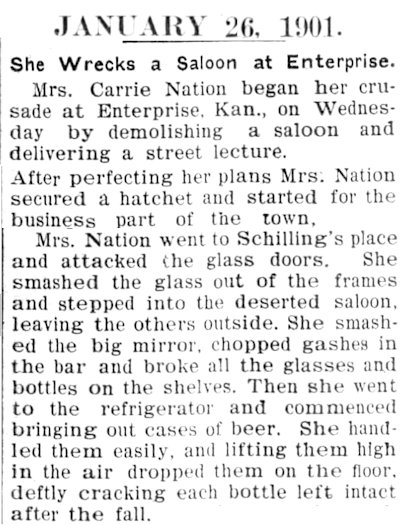

For example, on January 23 she delivered a hatchetation—and a lecture—in Enterprise, Kansas.

For example, on January 23 she delivered a hatchetation—and a lecture—in Enterprise, Kansas.

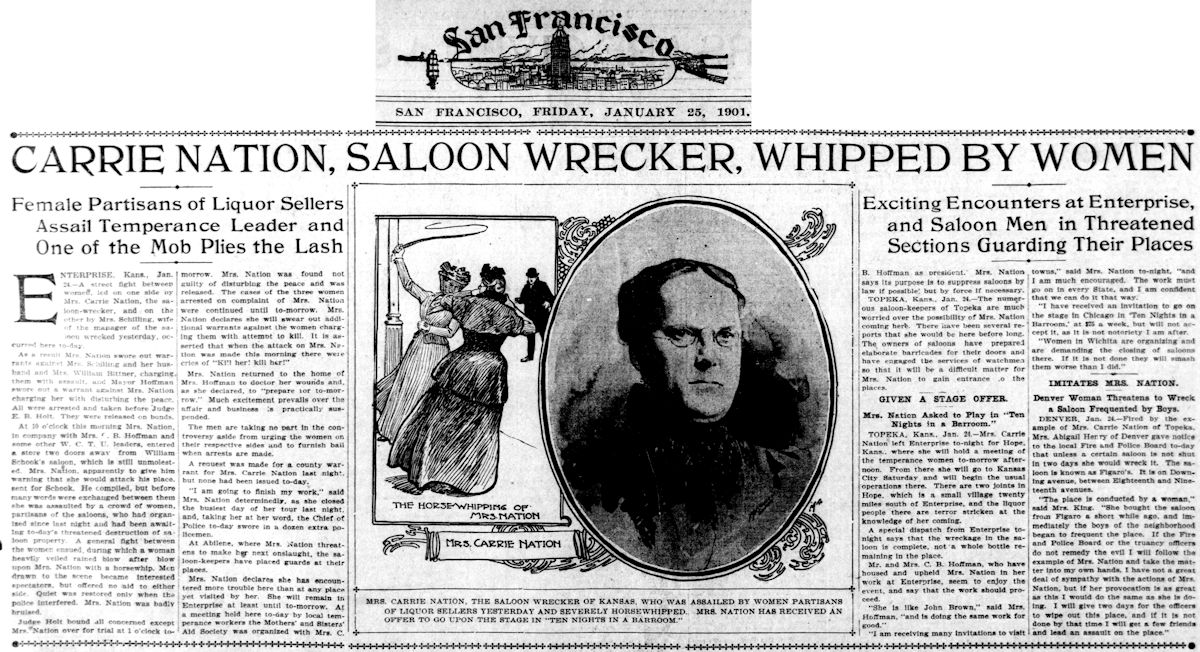

After the Enterprise hatchetation, Nation was attacked by “female partisans of liquor sellers.” One female partisan lashed Nation with a whip.

After the Enterprise hatchetation, Nation was attacked by “female partisans of liquor sellers.” One female partisan lashed Nation with a whip.

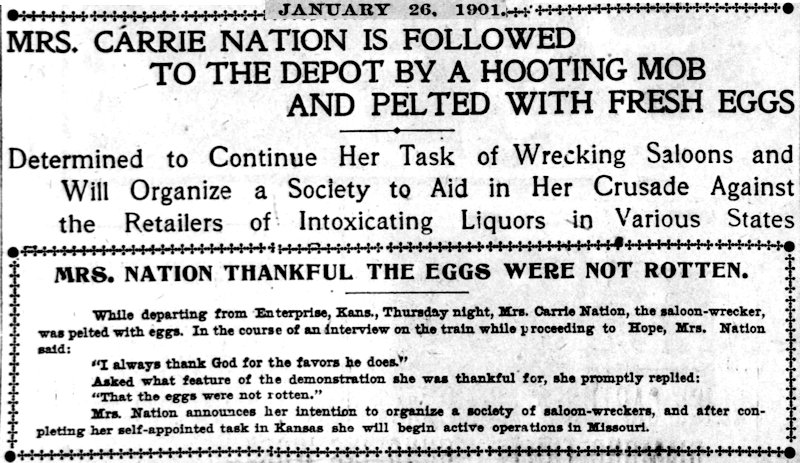

As Nation retreated to the train station in Enterprise she was pelted by eggs. She was grateful that the eggs were not rotten.

As Nation retreated to the train station in Enterprise she was pelted by eggs. She was grateful that the eggs were not rotten.

This cartoon appeared in the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune on March 6, 1901. As each new saloon went to smash, Nation’s notoriety spread. Now from the moment she arrived in a city her every step was followed by men and boys, many of them hoping that she would whip out her hatchet and raise a ruckus.

This cartoon appeared in the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune on March 6, 1901. As each new saloon went to smash, Nation’s notoriety spread. Now from the moment she arrived in a city her every step was followed by men and boys, many of them hoping that she would whip out her hatchet and raise a ruckus.

Carrie began to publish a newsletter—Smasher’s Mail—in 1901. Profits from the newsletter helped her pay her fines.

Carrie began to publish a newsletter—Smasher’s Mail—in 1901. Profits from the newsletter helped her pay her fines.

Although Carrie’s husband David approved of Carrie’s principles, he did not approve of her radicalism. In 1901 David divorced Carrie. Indeed Carrie Nation had become a polarizing figure. Some would canonize her; others would cannonize her. Preachers lauded her good works; saloonkeepers threatened her life. She was the object of caricatures and parodies. But she also inspired copy-cat attacks on saloons by women acting independently.

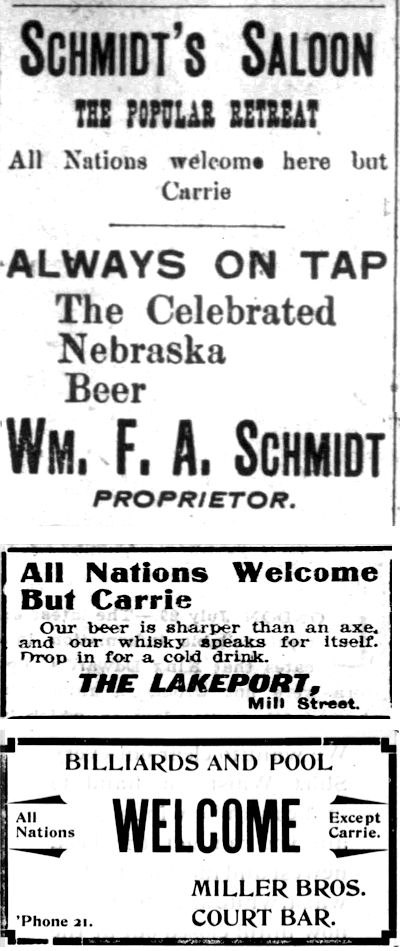

Saloons proclaimed “All Nations Welcome but Carrie” on banners and in newspaper ads.

Saloons proclaimed “All Nations Welcome but Carrie” on banners and in newspaper ads.

In 1903 Carrie Nation legally changed the spelling of her first name to “Carry” because she believed that her crusade would “Carry A Nation for prohibition.”

Carry Nation may have founded a WCTU branch, but the WCTU was more political than physical. The WCTU distanced itself from Carry’s hatchetry. Likewise, Carry came to distance herself from the temperance movement, defining herself more strictly as a prohibitionist.

In 1903 she said: “Temperance is a moderate use of whisky. Prohibition means abstaining from the awful habit. Hell is for the temperate or licensed criminals, and heaven is for prohibitionists.”

She described herself as “a bulldog running along at the feet of Jesus, barking at what He doesn’t like.”

But even as she raised her sights from temperance to prohibition, she began to temper her protests.

After a blitz of newspaper coverage of her hatchetations of 1901 she sheathed her hatchet for the most part.

Instead she and her disciples now entered saloons peacefully and merely preached and sang hymns. When asked to leave, they left.

By 1903 Carry Nation was fifty-seven years old. In 1903 the average life span of an American woman was fifty-two.

By 1903 Carry Nation was fifty-seven years old. In 1903 the average life span of an American woman was fifty-two.

Asked if she had more hatchetations planned, Carry told a reporter:

“I don’t do that kind of work anymore. I have realized that the saloon men are not to blame. It is the government. The saloon men are simply government agents.”

“And what has become of your famous hatchet?” she was asked

“Here’s my hatchet,” she said, taking a Bible from her satchel. “You know, I am simply following the word of God. He told me to go forth on this mission, and I obeyed. . . . The saloon men, the brewers, and the distillers, with the party politicians, have made this covenant with death, an agreement with hell.”

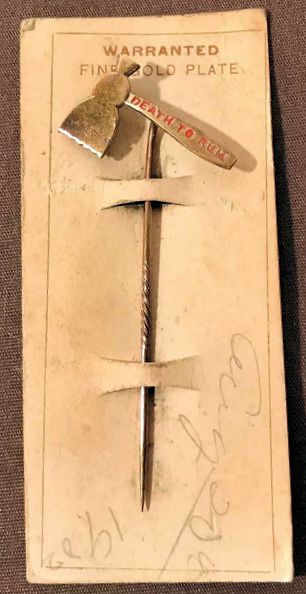

Now the “new” Carry Nation was jailed less often. When she was jailed, she paid her jail fines with profits of the sale of stickpins and brooches in the shape of hatchets. Engraved on the handle of the hatchets were the words “Death to Rum” or “Carry A Nation.”

Now the “new” Carry Nation was jailed less often. When she was jailed, she paid her jail fines with profits of the sale of stickpins and brooches in the shape of hatchets. Engraved on the handle of the hatchets were the words “Death to Rum” or “Carry A Nation.”

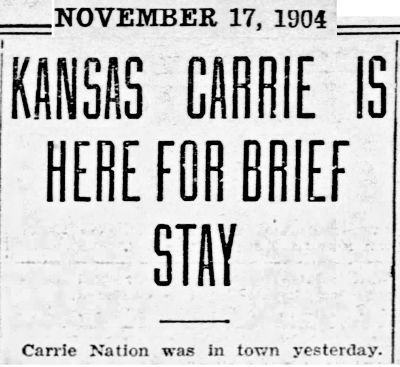

Carry Nation came to Cowtown in 1904. In fact, she was here twice in November. She may have put away her hatchet, but she remained “good copy” for newspapers.

Carry Nation came to Cowtown in 1904. In fact, she was here twice in November. She may have put away her hatchet, but she remained “good copy” for newspapers.

The Telegram wrote of her November 16 visit:

“She went to the Richelieu Hotel, registered, left her luggage, and started up the street. It was not many minutes until a large crowd of men and boys were following her. She visited several saloons and told the men behind the bar, ‘You are selling hell broth and ruining the homes.’ In several places the men replied that she had better attend to her own business and get out, and others she was permitted to argue the matter from her standpoint.

“The crowd following her kept getting larger and larger in evident anticipation that she would break a saloon or two, but she failed to perform.

“Mrs. Nation . . . did not hesitate to tell those present of the crimes they were permitting by allowing the liquor and cigarette habits to prevail . . . She blames 75 percent of the criminals of the country for their downfall to these two curses.

“. . . At the close of the speech she sold all the books and [stickpin] hatchets that she had with her. The demand was far greater than the supply, and all could not be taken care of.”

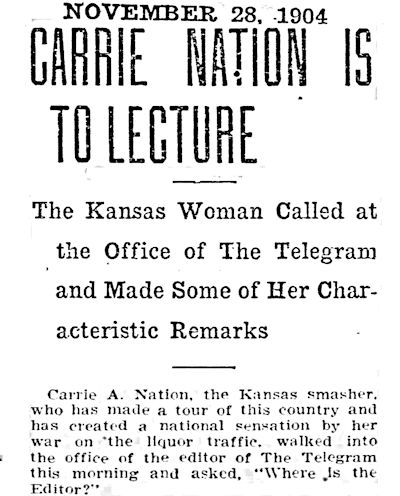

Carry came back to Cowtown on November 28.

Carry came back to Cowtown on November 28.

The Telegram wrote:

“Carrie A. Nation, the Kansas smasher, who has made a tour of this country and has created a national sensation by her war on the liquor traffic, walked into the office of the editor of the Telegram this morning and asked, ‘Where is the editor?’

“The presiding genius of the editorial department pleaded guilty to the soft impeachment, and the Kansas woman at once bluntly introduced herself, saying, ‘This is Carrie Nation.’ Looking about the room her eyes fell at once upon the handsome life-size picture of President Theodore Roosevelt, which graces the wall of the editor’s office.

“‘What are you doing with Roosevelt’s picture in here?’ she asked.

“‘Why, that is the picture of the president—our president—the president of the people of this country,’ explained the editor.

“‘No, he is not,’ she shouted. ‘He is the president of the brewers, the distillers, and the trusts. The brewers and the distillers and the trusts are opposed to the interests of the people. They have endorsed Mr. Roosevelt. Carrie Nation, the Home Defender, is against a man who is endorsed by the brewers, the distillers, and the trusts. Mr. Roosevelt talks about race suicide, yet he is endorsing a traffic which is killing off thousands of the race every year.’

“Mrs. Nation at this juncture espied a sack of tobacco on the desk. She emptied it upon the floor, saying tobacco is hurtful and should not be used. She saw a cigarette on the desk, and this she cast away, saying it is degrading to smoke cigarettes. . . .

“‘The position that Texas has taken in driving the saloons from her soil has been an inspiration to other states and a great credit to her own. I am not only in favor of prohibiting liquor, but the sale of cigarettes as well, as I believe that cigarettes are doing more to injure the young men of the country than all the liquor put together. It educates the appetite and prepares for other vices.’”

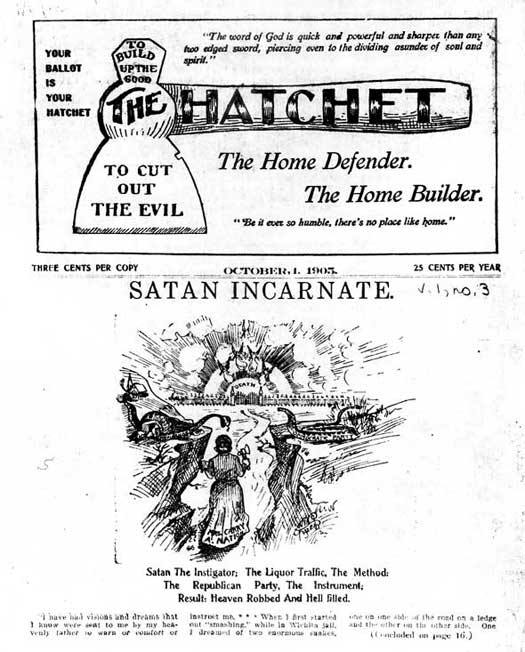

By 1905 Carry’s newsletter was The Hatchet.

By 1905 Carry’s newsletter was The Hatchet.

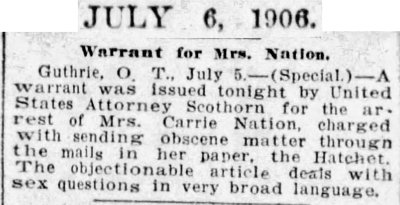

In 1906 a warrant for Carry Nation’s arrest for issued in Guthrie, Oklahoma. (Nation had moved to Guthrie to campaign for Oklahoma to be admitted to the Union as a dry state.) Authorities charged her with sending obscene matter through the mail via The Hatchet. The article in question was entitled “A Private Talk with Boys,” which “dealt with sex questions.”

In 1906 a warrant for Carry Nation’s arrest for issued in Guthrie, Oklahoma. (Nation had moved to Guthrie to campaign for Oklahoma to be admitted to the Union as a dry state.) Authorities charged her with sending obscene matter through the mail via The Hatchet. The article in question was entitled “A Private Talk with Boys,” which “dealt with sex questions.”

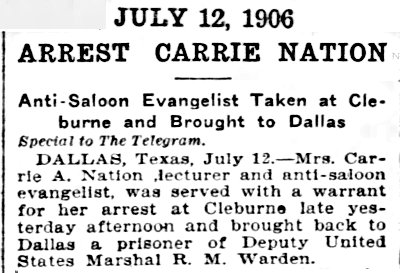

Nation was arrested in Cleburne while she was on a lecture tour. The obscenity charge was soon dropped.

Nation was arrested in Cleburne while she was on a lecture tour. The obscenity charge was soon dropped.

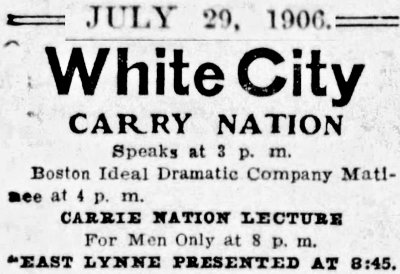

Free to continue her tour, on July 29 she lectured—twice—at Sam Rosen’s White City trolley park on the North Side. One lecture was “for men only.”

Free to continue her tour, on July 29 she lectured—twice—at Sam Rosen’s White City trolley park on the North Side. One lecture was “for men only.”

Nation used her lecture fees, like the sales of her newsletters and stickpins, to pay her fines and finance her crusade.

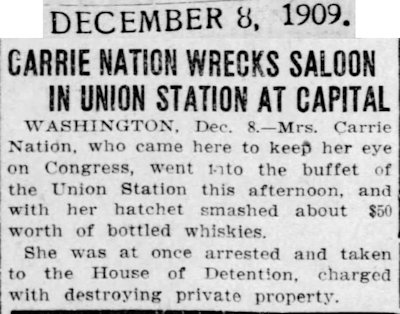

In 1909, perhaps overcome by nostalgia for the good ol’ days, Carry Nation got out her trusty hatchet one more time and broke some liquor bottles in the buffet of Union Station in Washington, DC.

In 1909, perhaps overcome by nostalgia for the good ol’ days, Carry Nation got out her trusty hatchet one more time and broke some liquor bottles in the buffet of Union Station in Washington, DC.

The next year she was back in Cowtown on May 19—the day the Earth passed through the tail of Halley’s Comet. By 1910 she had been arrested more than thirty times.

The next year she was back in Cowtown on May 19—the day the Earth passed through the tail of Halley’s Comet. By 1910 she had been arrested more than thirty times.

As always when she arrived in a town, people followed her every step. Two of those people on May 19 were reporters for the Star-Telegram and Record.

The Star-Telegram wrote:

“Like Halley’s comet, Carry Nation came and went. And she was just about as effective. No saloon licenses have been revoked. No bartenders have resigned their jobs. Cocktails are still concocted, and fizzes are still fizzing.

“Mrs. Nation spent two and a half hours in Fort Worth Thursday afternoon. She ‘bawled out’ a bartender at Thirteenth and Main streets [in Hell’s Half Acre]. She drew the attention of cigarette fiends to their ‘criminal vice.’ But that’s all. The hatchet remained unhatched, and the saloons continued to pass drinks across the bar.

“Mrs. Nation is 64 years old. Differing from the average woman, she doesn’t hesitate to tell her age. She has been in jail many times. But she doesn’t enjoy the confinement of a cell. That’s why she has stopped saloon smashing. To attack saloons with her little hatchet would only mean going to jail. And she thinks that she could do more good outside of jail than in it.

“‘Look at that cigarette fiend,’ she said as she walked up Main Street from the Union Depot. ‘The vile villain is puffing out tobacco smoke, and the smoke is blown back here. Do you realize that that is an insult? It is.’

“A saloon was passed just then.

“‘Just see that vile stuff,’ said Mrs. Nation. ‘My heart cries to me to go in and smash it. The saloon is the bar to heaven and the door to hell. Fort Worth is a great city. There are lots of good people here, but it is the worst cigarette smoking town in the country. . . . Don’t you know, young man, that the cigarette is the instrument of the devil? There’s one now. I’m going to put my heel on it. I crush the things just as I would crush the head of a snake.’

“And suiting her action to her words, Mrs. Nation stamped upon the stub of a cigarette that some smoker had thrown upon the sidewalk. The Union Station was approached just then, and Mrs. Nation invited the Star-Telegram man who had accompanied her in her walk through the central portion of town to enter the station with her.

“‘I want to present you with one of my little hatchets,’ she said. ‘It is inscribed with my name,’ and the reporter held his breath while Carry pinned the little golden hatchet on his coat lapel.

“‘I want to present you with one of my little hatchets,’ she said. ‘It is inscribed with my name,’ and the reporter held his breath while Carry pinned the little golden hatchet on his coat lapel.

“‘Do you smoke?’ she asked. And then he had to let his breath go and take chances on the little smasher detecting the odor of a recent highball.

“‘Yes,’ he replied, ‘but not cigarettes.’

“‘Well, that’s better, but don’t use tobacco at all. It is a stepping stone to hell.’”

The Record, too, noted Nation’s observations as she walked downtown:

“‘Look at that, a pool hall: the devil’s setting hen, hatching out vagrants, gamblers, and vice.’ She stopped and hurled this through the open door of a Main Street billiard hall. A pile of champagne bottles caught her eye as they nestled against the glass in the show window of a wholesale liquor house.

“‘Ugh,’ she shuddered, ‘it makes me want to smash things.’ Then calling into the door of the place she yelled: ‘Den of murderers, murderers of home and peace,’ and hurried on.”

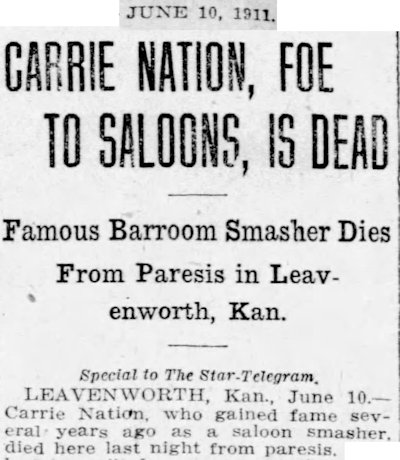

In 1911 Carry Nation died where it all had begun in 1900—Kansas. She was sixty-four.

In 1911 Carry Nation died where it all had begun in 1900—Kansas. She was sixty-four.

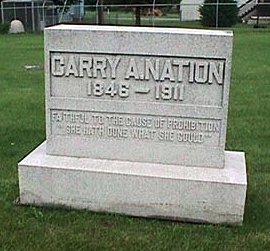

She is buried in Belton, Missouri. Her tombstone—erected by the WCTU—reads “Faithful to the cause of prohibition. She hath done what she could.”

She is buried in Belton, Missouri. Her tombstone—erected by the WCTU—reads “Faithful to the cause of prohibition. She hath done what she could.”

When “The Eyes of Texas” Were Upon Carry Nation

Carry Nation in her 1904 autobiography The Use and Need of the Life of Carrie A. Nation wrote of an incident: “I spoke in Austin, Texas . . . I went up to the state university with students who tried to get a hall for me to speak to them, but they could not. I spoke from the steps. In the midst of the speech and the cheers from the boys I heard a voice at my side. I looked, and there stood the Principal, Prexley Prather. He was white with excitement, saying: ‘Madam, we do not allow such.’ I said: ‘I am speaking for the good of these boys.’ ‘We do not allow speaking on the campus.’ I said: ‘I have spoken to the students at Ann Arbor, at Harvard, at Yale, and I will speak to the boys of Texas.’ The boys gave a yell.”

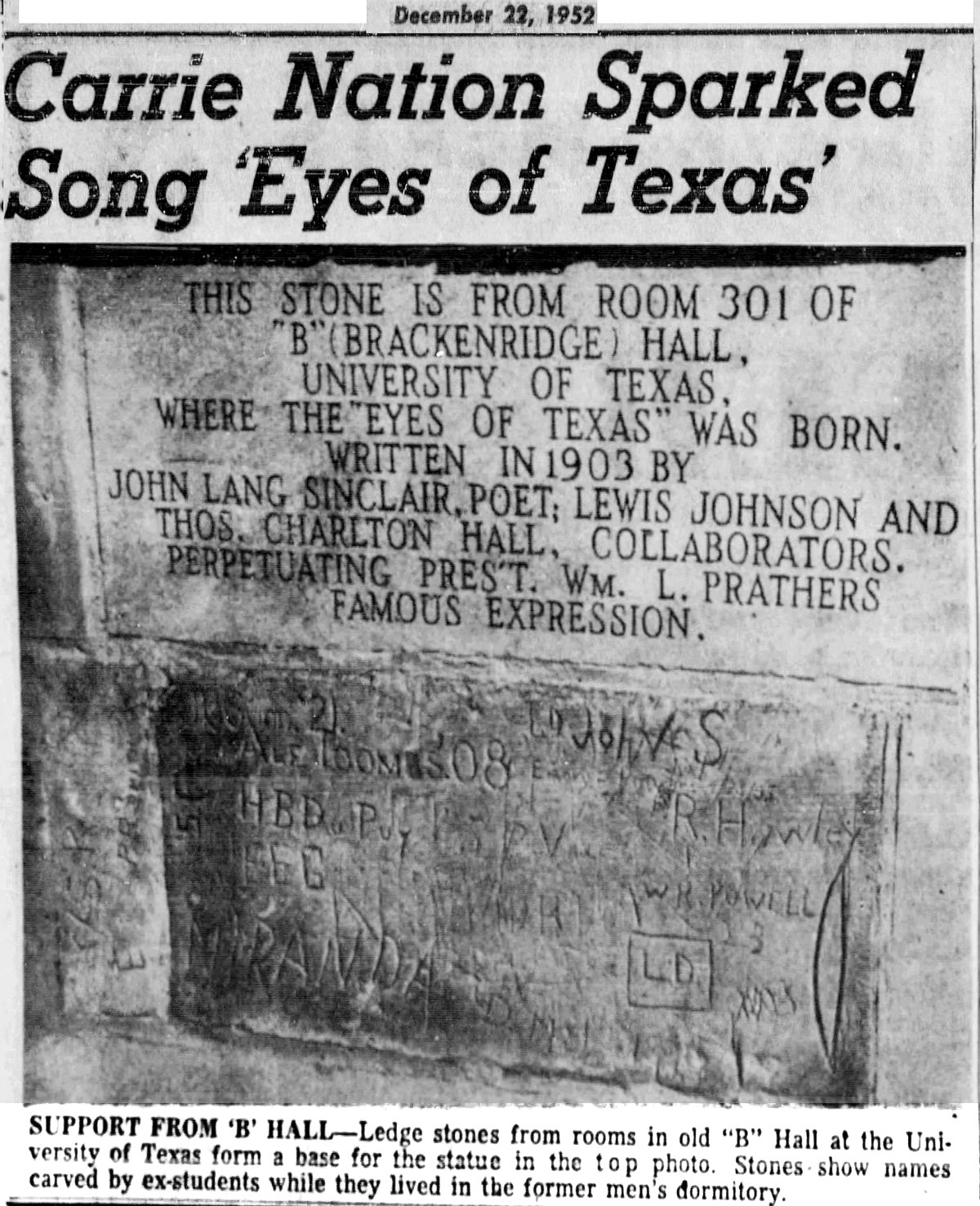

But there is more to that incident, according to Thomas Charlton Hall. In 1903 Hall was one of the co-writers of “The Eyes of Texas,” the school song of the University of Texas. In 1952 Hall recalled how the Carry Nation incident contributed—obliquely—to the song’s title:

But there is more to that incident, according to Thomas Charlton Hall. In 1903 Hall was one of the co-writers of “The Eyes of Texas,” the school song of the University of Texas. In 1952 Hall recalled how the Carry Nation incident contributed—obliquely—to the song’s title:

“[I] was a student in the Law Department of the University of Texas in the spring of 1903. Lewis Johnson of Jacksboro was in my class. We were members of the Southern Kappa Alpha Fraternity. Lewis was manager of the glee club, and I was his assistant in arranging a University Glee Club [minstrel] show at the Hancock Opera House in Austin in April 1903. We had three scenes and many numbers sung by the glee club. The song ‘I’ve Been Working on the Railroad,’ when sung, was encored at least four times, and the tune captivated the crowd. . . . Lewis and I went to his room in old ‘B’ Hall to discuss a change of program for the second performance, and it was here ‘The Eyes of Texas’ was born. . . . One bright spring morning as I approached the campus and passed Pat McCabe’s saloon I heard a commotion inside and heard Pat pleading, ‘Lady, don’t do that.’ Curiosity got the better of me because of hearing a woman in a beer parlor. I went in the back door. There stood a little old lady in a gray bonnet and gray dress, holding a hatchet in her hand, threatening to break the mirror in Pat’s bar, and he was walking in front of her to prevent it. I eventually persuaded her to accompany me to the campus and promised that she could talk to the student body . . . and help ‘save them.’ We waited on the south steps of the old Main Building until classes changed. Word was passed that Carrie Nation was waiting to speak to the student body on the south steps. . . . As she continued her talk, the cheers grew to such an extent as to be heard by that very genial proctor and secretary of the faculty, Judge James B. Clark, who came out of his office and listened for a few minutes. When he saw me he pointed his finger and said, ‘You are responsible for this disgraceful incident,’ . . . and he immediately went after President William Lambdin Prather, who in his stately manner stopped Carrie Nation in the middle of her speech and exhorted her for her conduct. Carrie was not to be outdone and argued with the president. The student body roared, ‘Stay with him, Carrie.’

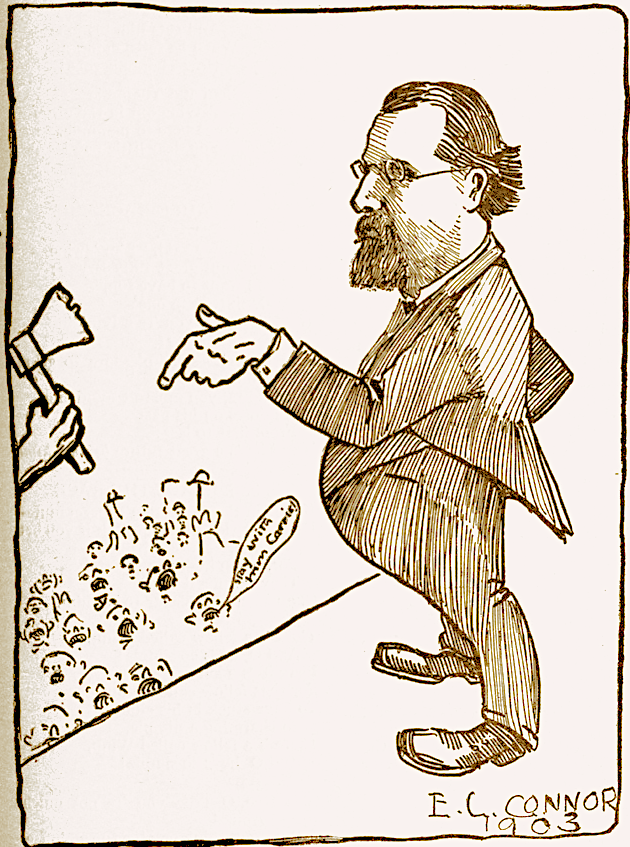

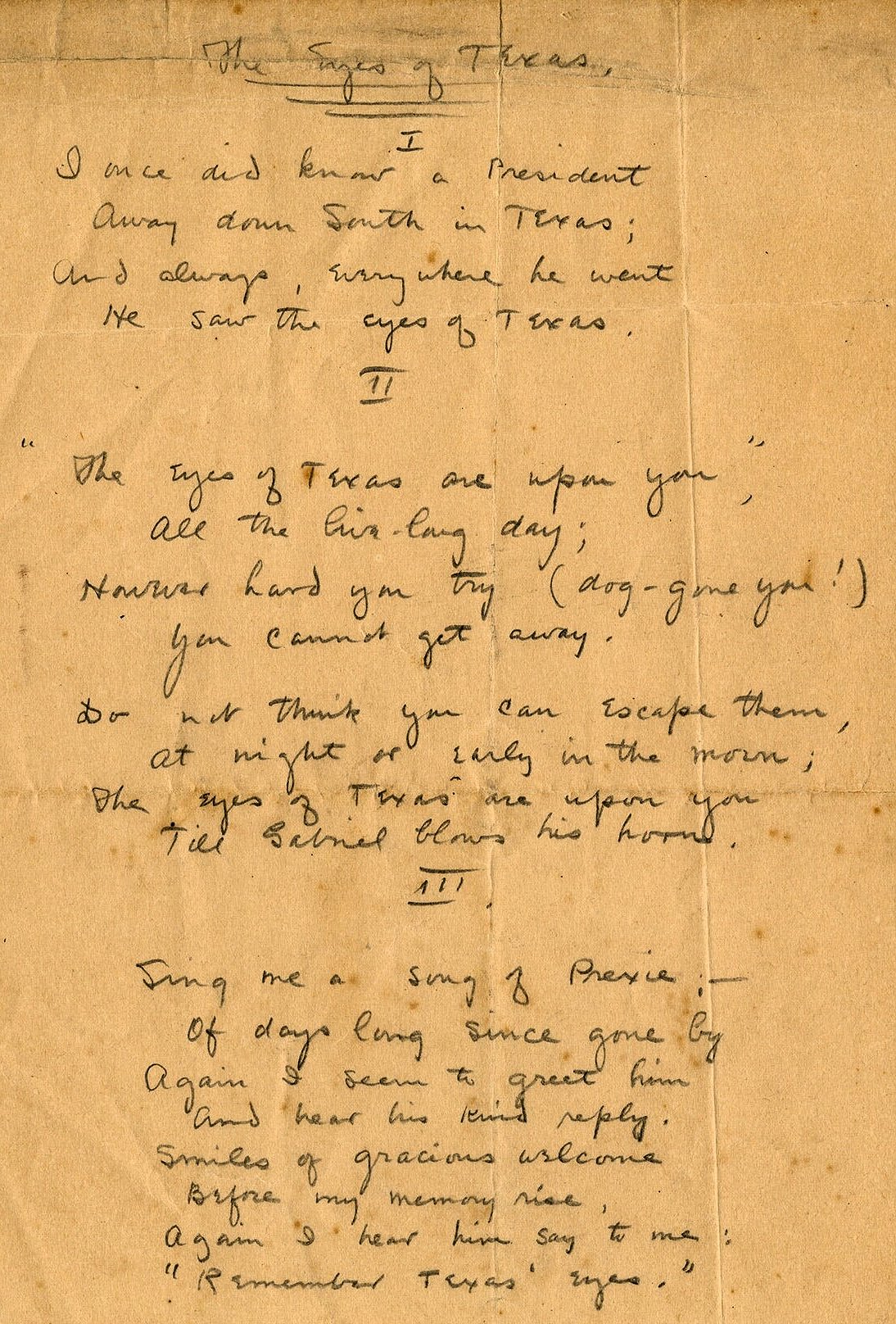

“A caricature of President Prather and the crowd yelling at Carrie was published in the 1903 Cactus [yearbook], page 253. The president in all his dignity raised his hands, stopped the cheering of the student body, and repeated several times, ‘Remember, young men, wherever you are and wherever you may be, the eyes of Texas are upon you. You are expected to uphold her tradition and not act as hoodlums and cheer this poor deluded woman’ . . . and really here it was that the phrase, ‘the eyes of Texas,’ was born. As we sat in Johnson’s room in old ‘B’ Hall, Johnson suggested that we write a parody to the tune ‘I’ve Been Working on the Railroad,’ and use ‘the eyes of Texas are upon you.’ We wrote and talked of the wording and called out the window to John Lang Sinclair, at the time considered the poet laureate of the university, to come over. We explained to him what we wanted. He pulled the brown wrapping paper off a Boche’s Laundry package and with a pencil, and our help, wrote the song ‘The Eyes of Texas.’”

“A caricature of President Prather and the crowd yelling at Carrie was published in the 1903 Cactus [yearbook], page 253. The president in all his dignity raised his hands, stopped the cheering of the student body, and repeated several times, ‘Remember, young men, wherever you are and wherever you may be, the eyes of Texas are upon you. You are expected to uphold her tradition and not act as hoodlums and cheer this poor deluded woman’ . . . and really here it was that the phrase, ‘the eyes of Texas,’ was born. As we sat in Johnson’s room in old ‘B’ Hall, Johnson suggested that we write a parody to the tune ‘I’ve Been Working on the Railroad,’ and use ‘the eyes of Texas are upon you.’ We wrote and talked of the wording and called out the window to John Lang Sinclair, at the time considered the poet laureate of the university, to come over. We explained to him what we wanted. He pulled the brown wrapping paper off a Boche’s Laundry package and with a pencil, and our help, wrote the song ‘The Eyes of Texas.’”

John Lang Sinclair’s handwritten first draft. (Photo from the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin.)

John Lang Sinclair’s handwritten first draft. (Photo from the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin.)

(There are differing accounts of the origin of the song.)

… Thanks again Mike…

… I will share this at my noon meeting, pretty sure everyone there will find something of interest in it…

… I know I have read this post before, apparently I am now seeing it with a new set of eyes, I love everything you post and cry every time I try to link only discover it has been deleted to free up space, please tell me how I can help financially support your endeavor that I find so valuable…

… Scott Pearce…

Thanks, Scott. I never delete a post. I may rewrite one and post it under a different URL. Also, some posts that have not yet been published have a URL that is not yet valid. Try keyword search next time you can’t find a post. And let me know if you come across a bad link.

Wow!!

Here’s another info! Carrie Nation gave her last lecture in Basin Park in Eureka Springs, Arkansas! I think there’s a plaque that says that. She had her stroke in the middle of lecture and so they eventually took her to Leavenworth, Kansas where she dies.

I used to go and hang out at Basin Springs Park and sell my pine needle baskets with other artists..when I lived in Arkansas. That’s how I know.