Back in the 1870s and 1880s, if you wanted to find Asa N. Fitzgerald, you would look in three places. You might find him in a church—preaching. If he wasn’t in a church preaching, you might find him in some mine or well—prospecting. If he wasn’t down some mine or well prospecting, you might find him in a courtroom—suing or being sued.

But today Asa N. Fitzgerald is best remembered for his role in making Fort Worth “Panther City.”

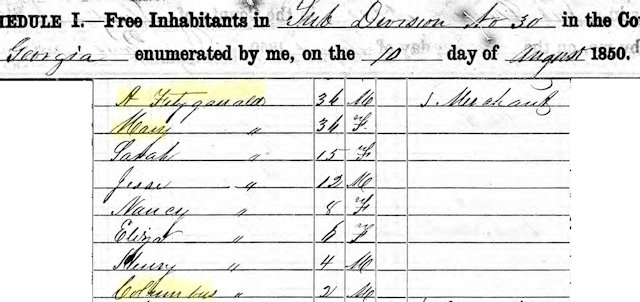

Asa N. Fitzgerald and wife Mary moved their family to Tarrant County from Georgia about 1864. Among Asa and Mary’s children was son Christopher Columbus Fitzgerald.

Reverend Fitzgerald in 1867 was co-founder of Fort Worth’s First Baptist Church and was its first pastor. The church reorganized in 1873.

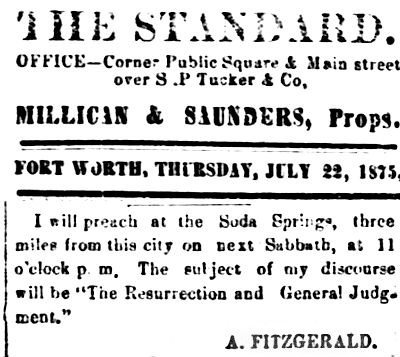

He also preached at the soda springs.

He also preached at the soda springs.

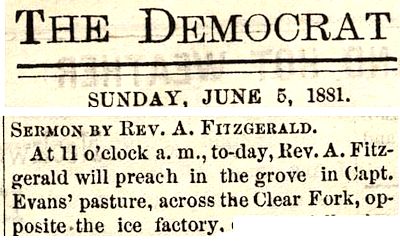

He preached in a grove of Sam Evans’s pasture across the river from the ice factory.

He preached in a grove of Sam Evans’s pasture across the river from the ice factory.

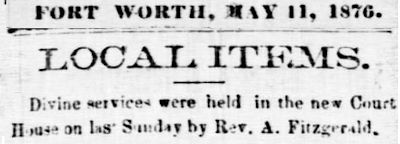

And after the courthouse burned in 1876 he preached at the dedication of the new courthouse.

And after the courthouse burned in 1876 he preached at the dedication of the new courthouse.

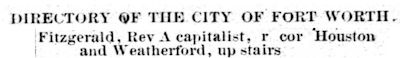

But in the 1877 city directory he listed himself as a “capitalist.” More specifically, the Fort Worth Democrat described Fitzgerald as “a mineral man from the feet up.”

But in the 1877 city directory he listed himself as a “capitalist.” More specifically, the Fort Worth Democrat described Fitzgerald as “a mineral man from the feet up.”

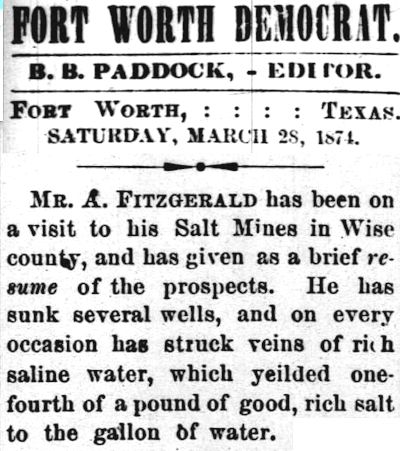

In 1874 he had salt mines in Wise County.

In 1874 he had salt mines in Wise County.

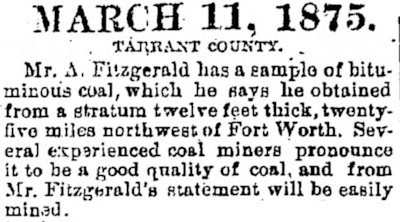

In 1875 he found a vein of coal twenty-five miles northwest of Fort Worth.

In 1875 he found a vein of coal twenty-five miles northwest of Fort Worth.

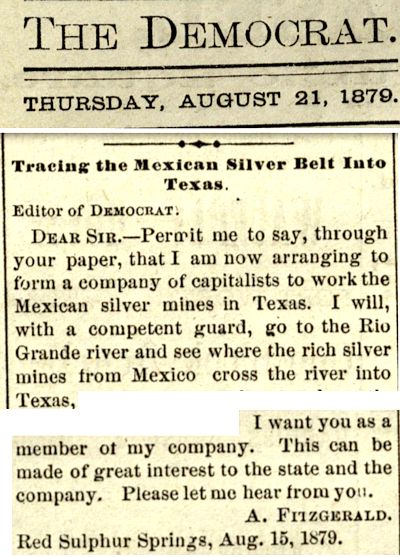

In 1879 he advertised for investors to finance his prospecting for the “Mexican silver belt” in Texas. Note that Fitzgerald wrote from Red Sulphur Springs.

In 1879 he advertised for investors to finance his prospecting for the “Mexican silver belt” in Texas. Note that Fitzgerald wrote from Red Sulphur Springs.

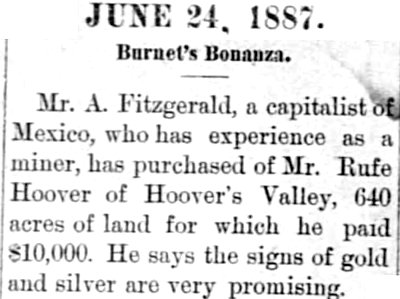

And for a while he apparently lived in Mexico. In 1887 he found “signs of gold and silver” in Hoover’s Valley in Burnet County.

And for a while he apparently lived in Mexico. In 1887 he found “signs of gold and silver” in Hoover’s Valley in Burnet County.

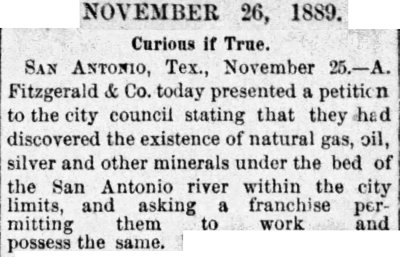

He also asked the city of San Antonio for a franchise to extract “natural gas, oil, silver, and other minerals” from under the San Antonio River. The city declined.

He also asked the city of San Antonio for a franchise to extract “natural gas, oil, silver, and other minerals” from under the San Antonio River. The city declined.

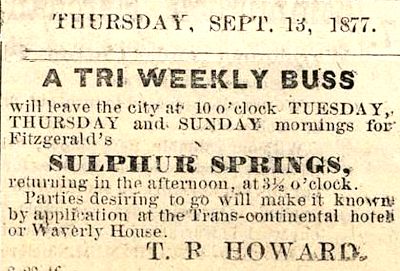

Closer to home, in 1877 he commercialized a sulphur spring ten miles east of town. Three days a week a “buss” (for “omnibus,” a horse-drawn public coach) carried people to and from the springs. One omnibus depot was the Trans-Continental Hotel.

Closer to home, in 1877 he commercialized a sulphur spring ten miles east of town. Three days a week a “buss” (for “omnibus,” a horse-drawn public coach) carried people to and from the springs. One omnibus depot was the Trans-Continental Hotel.

The area became known as “Red Sulphur Springs” or just “Sulphur Springs.”

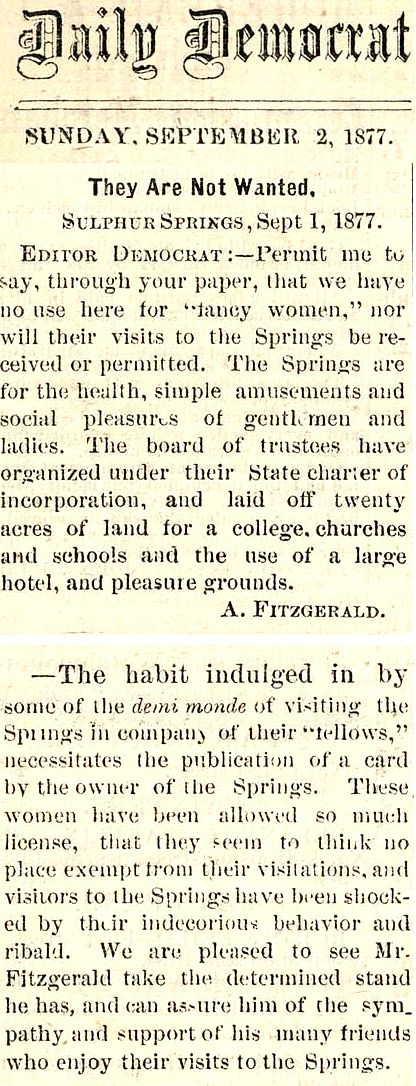

Fitzgerald complained in the Democrat that Cowtown’s “fancy women” (prostitutes) were going out to the sulphur springs. Fitzgerald said he had plans for a church, college, school, hotel, and “pleasure grounds” at the springs, similar to Ederville. The Democrat bemoaned Fort Worth’s “demi monde” (prostitutes) going to the springs with their “fellows.”

Fitzgerald complained in the Democrat that Cowtown’s “fancy women” (prostitutes) were going out to the sulphur springs. Fitzgerald said he had plans for a church, college, school, hotel, and “pleasure grounds” at the springs, similar to Ederville. The Democrat bemoaned Fort Worth’s “demi monde” (prostitutes) going to the springs with their “fellows.”

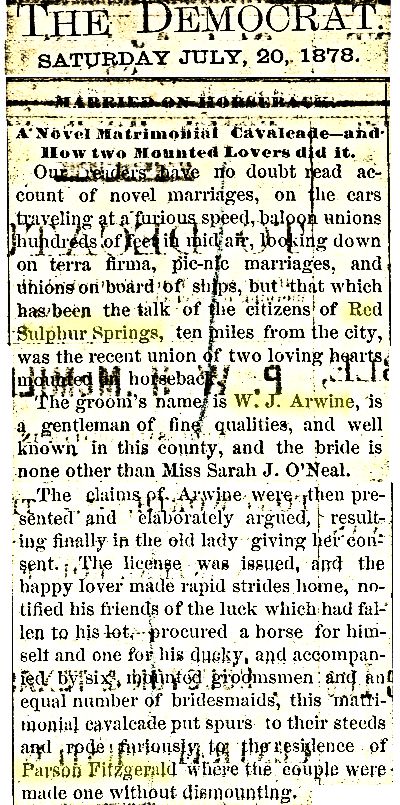

The Red Sulphur Springs area also was known as “Arwine” after a family who settled there. In fact, in 1878 Fitzgerald, who by then lived at the springs, conducted the marriage ceremony of W. J. Arwine and his bride—both on horseback The Red Sulphur Springs/Arwine area is now part of Hurst.

The Red Sulphur Springs area also was known as “Arwine” after a family who settled there. In fact, in 1878 Fitzgerald, who by then lived at the springs, conducted the marriage ceremony of W. J. Arwine and his bride—both on horseback The Red Sulphur Springs/Arwine area is now part of Hurst.

This 1895 map shows an Arwine School and the homes of an Arwine, a Fitzgerald, and a Hurst in the area.

This 1895 map shows an Arwine School and the homes of an Arwine, a Fitzgerald, and a Hurst in the area.

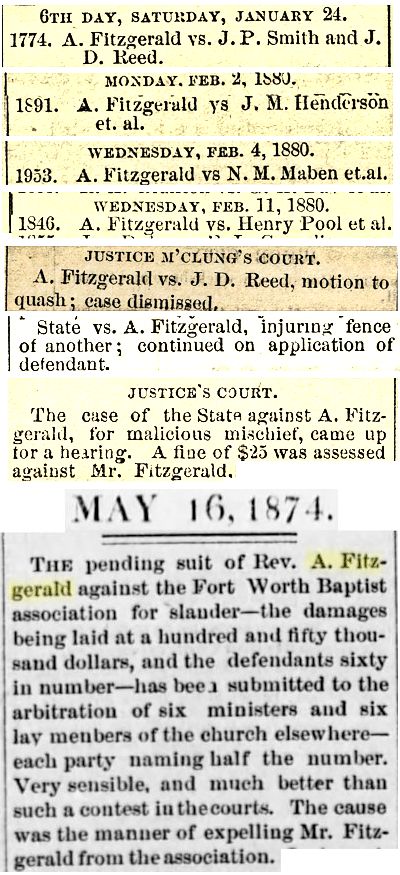

When Fitzgerald was not in a church or in a mine, he was in a courtroom, suing or being sued. He sued even his own religious organization after the Fort Worth Baptist Association expelled him. He sued sixty members for slander to the tune of $150,000 ($3.4 million today).

When Fitzgerald was not in a church or in a mine, he was in a courtroom, suing or being sued. He sued even his own religious organization after the Fort Worth Baptist Association expelled him. He sued sixty members for slander to the tune of $150,000 ($3.4 million today).

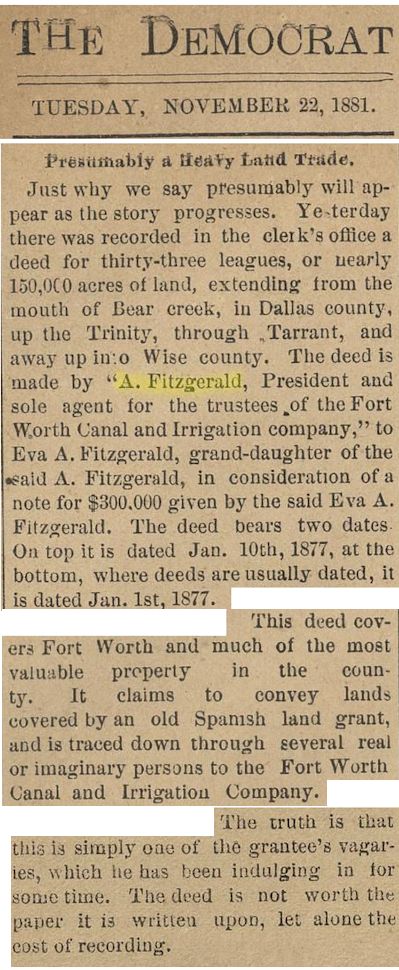

He also found time to claim to have a deed, passed down from a Spanish land grant, that gave his “Fort Worth Canal and Irrigation Company” title to almost 150,000 acres in north Texas, including all of Fort Worth. If his claim was denied, he said, he would make trouble.

He also found time to claim to have a deed, passed down from a Spanish land grant, that gave his “Fort Worth Canal and Irrigation Company” title to almost 150,000 acres in north Texas, including all of Fort Worth. If his claim was denied, he said, he would make trouble.

He never did.

In 1873 Fitzgerald, along with Sam Evans and David (“Tuck”) Boaz, was charged with violating the “ku klux bill,” which probably refers to the Enforcement Act of 1871, known as the “Ku Klux Klan Act,” which made federal offenses of a number of the Klan’s intimidation tactics. The Democrat referred to the act as a “damnable piece of tyranny.”

In 1873 Fitzgerald, along with Sam Evans and David (“Tuck”) Boaz, was charged with violating the “ku klux bill,” which probably refers to the Enforcement Act of 1871, known as the “Ku Klux Klan Act,” which made federal offenses of a number of the Klan’s intimidation tactics. The Democrat referred to the act as a “damnable piece of tyranny.”

Fort Worth historian Dr. Richard F. Selcer and retired police sergeant and historian Kevin Foster in their Written in Blood: The History of Fort Worth’s Fallen Lawmen call Reverend Fitzgerald a “confirmed bigot” who as a father passed his bigotry on to his son, City Marshal Christopher Columbus Fitzgerald.

But Reverend Asa N. Fitzgerald’s redeeming act and lasting claim to fame were his interpretation of an indentation in the dirt. See, after the Texas & Pacific railroad reached Dallas in 1873 but failed to reach Fort Worth, Fort Worth’s population declined while the population of Dallas increased. Fort Worth fretted; Dallas gloated.

One morning in January 1875 Fitzgerald summoned Howard Peak, then nineteen. In the 1920s Peak would write a series of articles about Fort Worth history for the Star-Telegram. In 1922 Peak recalled how Fort Worth’s Panther legend began.

Peak began his reminiscence by saying Fitzgerald was “a very devout and eccentric man.” Peak further recalled: “One spring morning I was called . . . to where he was, to see the place where a panther had laid down the night previous. This was according to the parson. There was the very place, just in the middle of Weatherford Street in the block west of the square. Now it was a question of whether the place was made by a panther or an ordinary calf, but the parson always contended it was made by the former.’”

No one actually saw the panther, mind you. They merely accepted Fitzgerald’s interpretation of an indentation in the dirt.

By February the yarn had reached to Dallas, where it got some embellishment by Robert Cowart, a former Fort Worth resident. Cowart wrote a tongue-in-cheek article in the Dallas Daily Herald in which he claimed that Fort Worth, denied the railroad, had become such a sleepy “suburban village” that one night a panther had come up from the river bottom, had wandered the downtown streets “at his own sweet will,” and had laid down to sleep on a major city thoroughfare.

Cowart wrote of the alleged panther: “His tracks were seen by the terror-stricken natives.”

Fort Worth townspeople, Cowart wrote, called a public meeting (“Fort Worth never does anything without a meeting,” he wrote).

“Parson Fitzgerald,” Cowart wrote, drove a stake into the ground “whar the pant[h]er had laid down.”

Then “Parson Fitzgerald, in a few appropriate remarks, explained the objects of the meeting by stating that it would never do for it to get out that a ‘pant[h]er’ had walked those streets, for the Dallas people and their confounded papers would never let up on Fort Worth, and that it would deter people from investing, and ruin the prospects of their city as a railway center.”

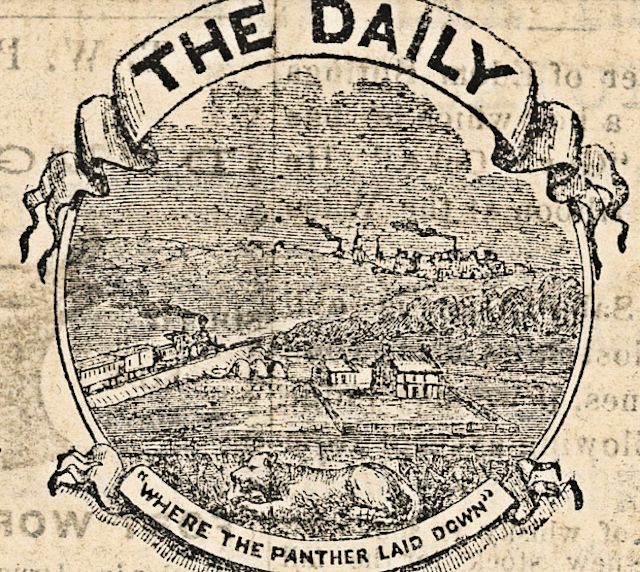

But Fort Worth, not Dallas, would have the last laugh. Rather than be shamed by the teasing, Fort Worth—which heretofore had called itself, rather regally, “Queen City of the Prairies”—embraced the legend of the sleeping panther and began rebranding itself. From the panther featured on the Democrat’s nameplate to the panther emblem on Fort Worth police badges to the panther cub mascot of the fire department, Fort Worth would become “Panther City.”

But Fort Worth, not Dallas, would have the last laugh. Rather than be shamed by the teasing, Fort Worth—which heretofore had called itself, rather regally, “Queen City of the Prairies”—embraced the legend of the sleeping panther and began rebranding itself. From the panther featured on the Democrat’s nameplate to the panther emblem on Fort Worth police badges to the panther cub mascot of the fire department, Fort Worth would become “Panther City.”

And the rest—thank you, Reverend Fitzgerald—is hisstory.