When he was born, and the doctor held him upside down and spanked him on the backside, he probably cried, “I object!”

William Pinckney McLean Jr. was born with a law book in his cradle. The son of an attorney, he would become an attorney himself and the father of two more attorneys.

William Pinckney McLean Jr. was born with a law book in his cradle. The son of an attorney, he would become an attorney himself and the father of two more attorneys.

McLean was born in 1872 in Mount Pleasant in east Texas. His father, William Pinckney McLean Sr., was a state legislator, Confederate army major, U.S. congressman, a member of the convention that adopted the Texas Constitution in 1876, a member of the Texas Railroad Commission, and a judge of the Fifth Judicial District. Judge McLean died in Fort Worth in 1925. A junior high school was named for him in 1936.

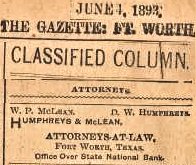

W. P. McLean Sr. was practicing law in Fort Worth in 1893.

W. P. McLean Sr. was practicing law in Fort Worth in 1893.

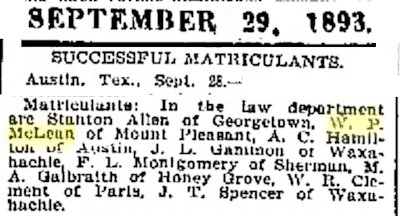

Son W. P. McLean Jr. attended high school in Austin and college at Southwestern Presbyterian University in Clarksville, Tennessee. In 1893 he was back in Austin, enrolling in the University of Texas law school. According to the Star-Telegram, McLean was captain and quarterback of the first football team at the University of Texas.

Son W. P. McLean Jr. attended high school in Austin and college at Southwestern Presbyterian University in Clarksville, Tennessee. In 1893 he was back in Austin, enrolling in the University of Texas law school. According to the Star-Telegram, McLean was captain and quarterback of the first football team at the University of Texas.

After graduation McLean returned to east Texas and opened his law practice in Titus County. In 1898 he was elected county attorney. He was re-elected in 1900 but resigned to move to Fort Worth.

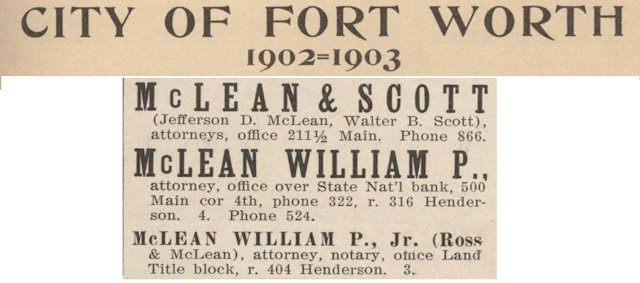

By 1902 W. P. McLean Jr., brother Jefferson Davis McLean, and father W. P. McLean Sr. were practicing law in Fort Worth. In 1904 W. P. Jr. joined the law firm of McLean and Scott, which had been formed by brother Jefferson Davis McLean and Walter B. Scott. Jefferson Davis McLean was shot to death while he was county attorney in 1907, and W. P. McLean Jr. continued the partnership with Scott. W. P. McLean Sr. joined the firm about 1912.

By 1902 W. P. McLean Jr., brother Jefferson Davis McLean, and father W. P. McLean Sr. were practicing law in Fort Worth. In 1904 W. P. Jr. joined the law firm of McLean and Scott, which had been formed by brother Jefferson Davis McLean and Walter B. Scott. Jefferson Davis McLean was shot to death while he was county attorney in 1907, and W. P. McLean Jr. continued the partnership with Scott. W. P. McLean Sr. joined the firm about 1912.

W. P. McLean Jr. soon developed a reputation as an able attorney. In fact, historians Dr. Richard Selcer and Kevin Foster write in Written in Blood that McLean was “considered by many to be the finest criminal lawyer in the Southwest, and certainly the most colorful.”

McLean was known as “Wild Bill” because of his booming voice and dramatic demeanor in the courtroom.

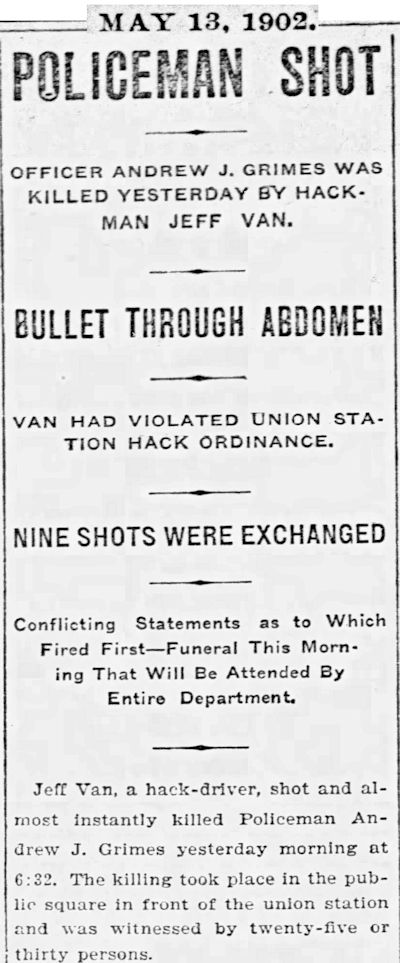

One of Wild Bill’s first high-profile criminal cases came in 1902.

As the twentieth century began, traffic around Fort Worth’s Texas & Pacific passenger terminal was congested: Streetcars, horse-drawn vehicles, and even a few automobiles clanged, neighed, and chugged as they clogged the adjacent streets and dodged each other and scurrying pedestrians. A major contributor to the problem was hacks (horse-drawn taxis), whose drivers competed for passengers at the station. In response the city passed an ordinance requiring hack drivers to park across the street from the station and to not cross to the station side of the street until summoned by a passenger.

Predictably, hack drivers did not like the ordinance. One driver in particular, Jeff Vann, had violated the ordinance several times.

About 6:30 on the morning of May 12, 1902 Vann pulled his hack up to the curb at the station while police officer Andrew Grimes was standing nearby.

Grimes told Vann to move his hack to the other side of the street. Vann refused and told Grimes that he intended to continue to violate the ordinance. Grimes wrote out a citation and told Vann to sign it. Vann refused.

Grimes said, “Then you’d better prepare to go along with me [to jail].”

Vann lifted the seat of his hack and pulled out a pistol.

“This is the way I go,” Vann said as he began firing down at Grimes. Horses reared, people screamed. Grimes held his nightstick in one hand and his ticketbook in the other hand. Before he could draw his pistol, he had been shot once. As he staggered he fired back at Vann, but his aim was wild.

The two men fired a total of nine shots.

Ten minutes later officer Andrew Grimes, wearing badge number 13, was dead.

The Register wrote that it was “almost miraculous” that no one else at the crowded station was killed, especially by the wild shots fired by officer Grimes as he collapsed. One hack horse and one man were grazed.

Vann was disarmed by police Captain Joe Witcher and station master J. J. Fulford.

Vann was charged with murder. At his trial he was defended by the law firm of Wynne, McCart, and Bowlin.

Vann was charged with murder. At his trial he was defended by the law firm of Wynne, McCart, and Bowlin.

When Vann went on trial his defense attorneys argued (1) that the hack ordinance was unconstitutional and thus officer Grimes had no right to enforce it against Vann and (2) that officer Grimes fired the first shot and that Vann acted in self-defense when he returned fire.

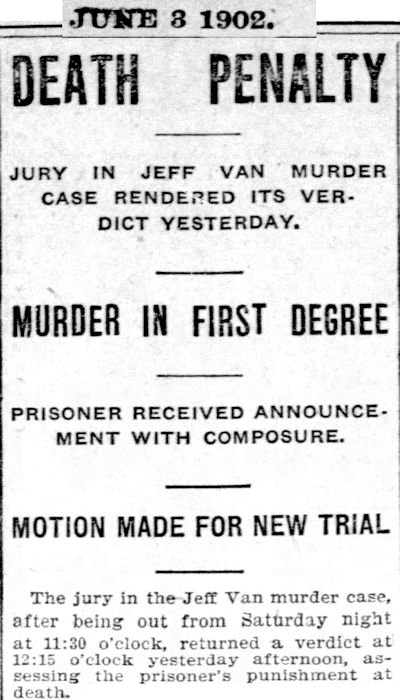

Vann was found guilty and sentenced to hang.

Vann was found guilty and sentenced to hang.

Unperturbed, Vann lit a cigar as defense attorney McCart immediately filed a motion for a new trial on the basis of errors in the first trial. A second trial was granted.

Unperturbed, Vann lit a cigar as defense attorney McCart immediately filed a motion for a new trial on the basis of errors in the first trial. A second trial was granted.

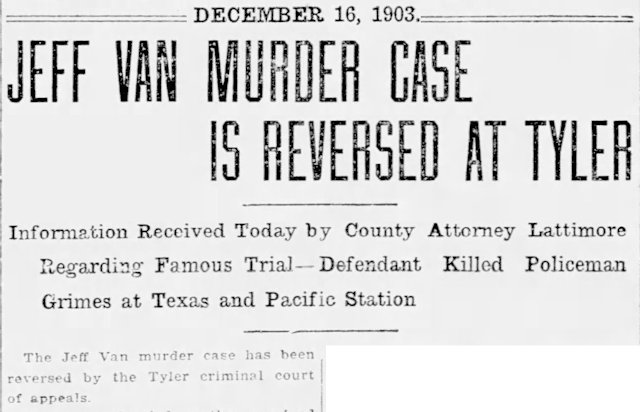

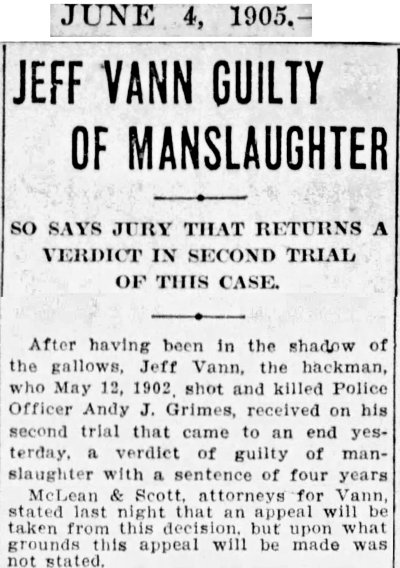

W. P. McLean Jr. took over Vann’s defense for the second trial. At the second trial McLean, too, argued that Vann had shot Grimes in self-defense. But this time McLean persuaded the jury to convict Vann of the lesser crime of manslaughter, not murder.

W. P. McLean Jr. took over Vann’s defense for the second trial. At the second trial McLean, too, argued that Vann had shot Grimes in self-defense. But this time McLean persuaded the jury to convict Vann of the lesser crime of manslaughter, not murder.

Thus, Jeff Vann escaped the gallows and served only four years in prison. He was released in 1909.

Fast-forward to 1911 and the genesis of one of the most audacious crime stories in Fort Worth history. In Amarillo on October 13 Mrs. Lena Sneed told her husband, cattleman John Beal Sneed, that after eleven years of marriage she no longer loved him and instead was in love with cattleman Albert Gallatin Boyce Jr. She told her husband that she and Boyce planned to run away to South America, taking the Sneeds’ two children with them.

Sneed, declaring his wife to be temporarily insane, on October 17 (their anniversary) had her committed to Arlington Heights Sanitarium in Fort Worth. (Lena’s parents insisted that she was sane and that Sneed had her cloistered to keep Lena and Boyce apart.)

Lena was miserable in the sanitarium. She wrote to paramour Boyce: “For God’s sake, get me away from here.”

Boyce withdrew $101,000 ($2.5 million today) from his bank in Amarillo and came to Fort Worth.

Lena was under guard at the sanitarium but was allowed to leave the premises in the custody of her nurse. So, on November 10 Lena arranged to rendezvous with Boyce at the train station, and they snuck off to Canada.

The next day Sneed arrived in Fort Worth to search for his AWOL wife. He swore out complaints accusing Boyce of abduction and kidnapping.

Subsequently Lena and Boyce were arrested in Winnipeg.

Four days later Mr. and Mrs. A. G. Boyce Sr. arrived in Fort Worth. Boyce Sr. began working to get the charges against his son dropped and to fight extradition of his son from Canada.

On December 30 Boyce Jr. was indicted for abduction and kidnapping.

On January 1, 1912 Sneed arrived in Winnipeg to reclaim his wife, but Lena told him that she would remain with Boyce Jr.

But the next day Lena relented and left with her husband for the States.

On January 7 Boyce Jr. announced that he was going to remain in Canada. Two days later Boyce, facing extradition, disappeared from the immigration hall where he was being held.

On January 13 Sneed returned his wife to the Arlington Heights Sanitarium. Meanwhile, the state dropped charges of abduction and kidnapping against Boyce Jr.

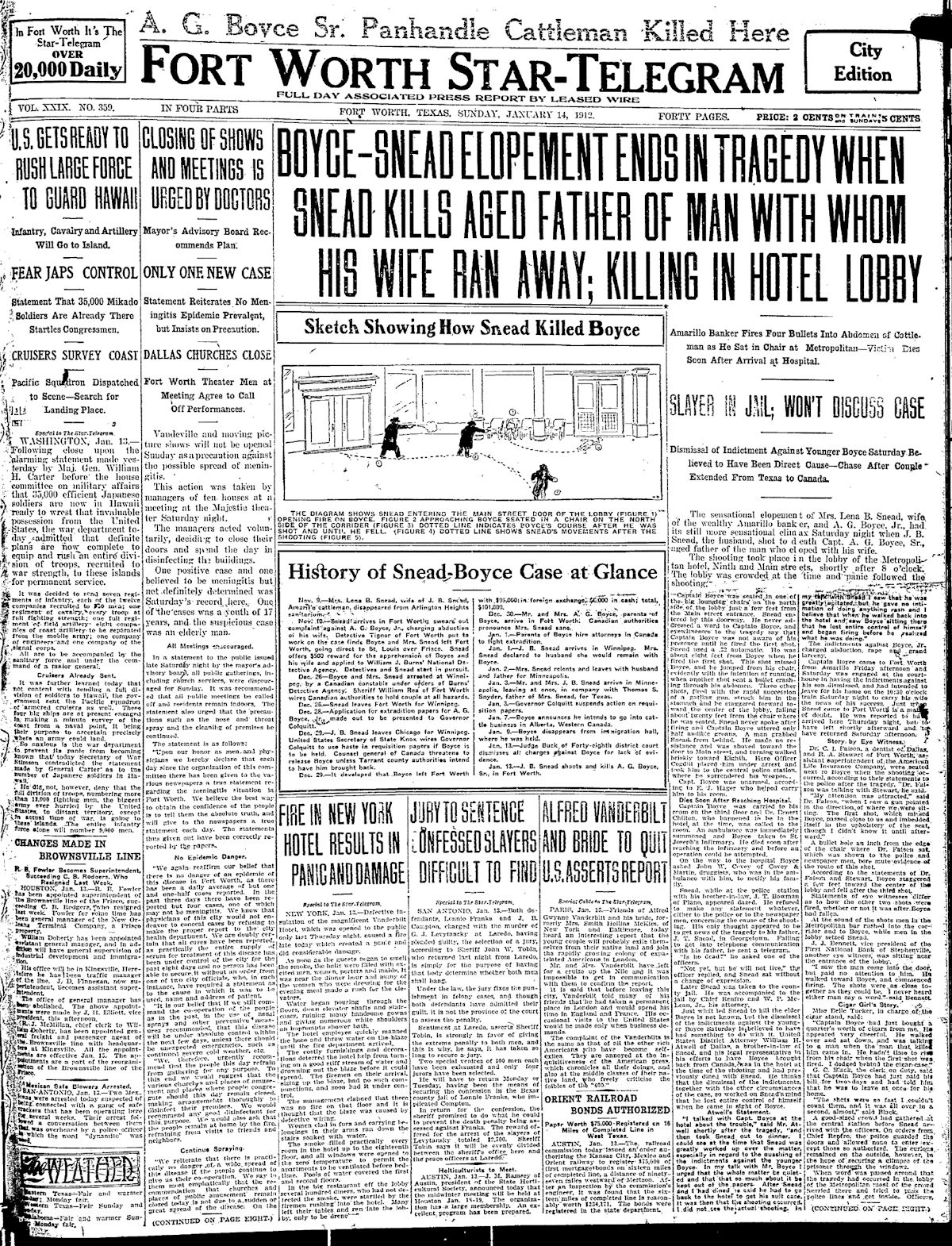

And that’s when John Beal Sneed burst into the lobby of Fort Worth’s Metropolitan Hotel and shot to death Albert Gallatin Boyce Sr. as Boyce sat in a chair. Boyce, seventy, was a prominent Amarillo banker and cattleman. Sneed blamed Boyce Sr. for getting the charges against Boyce Jr. dropped and for helping Boyce Jr. break up Sneed’s marriage by helping Lena to escape from the sanitarium.

And that’s when John Beal Sneed burst into the lobby of Fort Worth’s Metropolitan Hotel and shot to death Albert Gallatin Boyce Sr. as Boyce sat in a chair. Boyce, seventy, was a prominent Amarillo banker and cattleman. Sneed blamed Boyce Sr. for getting the charges against Boyce Jr. dropped and for helping Boyce Jr. break up Sneed’s marriage by helping Lena to escape from the sanitarium.

Sneed was charged with murder. He hired Wild Bill McLean as defense attorney.

During Sneed’s trial for killing Boyce Sr. McLean argued that Sneed was not guilty of murder because Sneed had killed the senior Boyce because Boyce Sr. had aided Boyce Jr. in the son’s attempt to win Mrs. Sneed away from Mr. Sneed.

In other words, McLean and Sneed were invoking the “unwritten law” as a self-defense against a charge of murder.

What was the unwritten law?

According to the Buffalo Law Review, the unwritten law was an uncodified constraint that protected “those who killed to defend the honor of women. . . . a husband, brother, or father could justifiably kill any man who had a sexual relationship outside of marriage with the killer’s wife, daughter, sister, or mother.”

The Review adds: “Criminal defendants who could convince a jury that they killed in defense of the sanctity of their home, and the virtue of their women, were almost certain to be acquitted.”

Indeed, in the twentieth century a defense of the unwritten law was successful for at least three other local men charged with murder: Dee Estes, Reverend C. C. Reneau, and William A. Jobe.

At Sneed’s trial McLean in his closing argument to the jury praised Sneed as a reluctant killer who had killed Boyce Sr. to protect Sneed’s home. McLean also vilified victim Boyce Sr. for slandering Mrs. Sneed and for helping Boyce Jr. break up the Sneed home:

“God Almighty never intended that the jail doors or the doors of the penitentiary should ever open to receive Beal Sneed, for he is one of the noblest protectors of home and womanhood that I have ever seen. Was the penitentiary made for such as him? I say no! The penitentiary was intended for the punishment of criminals. Do you want to deter men from protecting their homes? I say that whenever a home is broken up there should be a killing, and a killing of every one connected with it.

“‘Why,’ they say, ‘he [Sneed] killed the wrong man.’ They say, ‘Why didn’t he kill Al Boyce Jr.?’ Old man Boyce was just as guilty as was his son, for he had been assisting and encouraging him in keeping this defendant’s wife out of his reach.”

To the jury McLean painted a dire picture of the fate of the Sneed children if Sneed were convicted and his children were fated to live with Al Boyce Jr. and Mrs. Sneed: “If Beal Sneed goes to the penitentiary, I hope that you men may not pick up a newspaper next winter and read that his children are roaming the forests of Canada, freezing and starving. And that’s what may happen if they are ever placed under his [Boyce’s] control. . . . I can see Beal Sneed’s little children crouched down in a corner when Al Boyce comes home because they are afraid of him. Think of your own children—will you place [them] in [the] charge of this drunkard and this practically insane mother? That’s what you will do if you don’t send this protector [Sneed] back to protect her.

“I know that Beal Sneed never had murder in his heart. I know they speak of that bullet-riddled body [of Boyce Sr.], but look at this defendant’s bleeding heart. Again I think of his little children—I see them in their little snow-white nighties, saying their

“‘Now I lay me down to sleep,

‘I pray Thee, Lord, my soul to keep

‘If I should die before I wake

‘I pray You won’t let Al Boyce my soul take.’”

The trial went to the jury on February 24.

The trial went to the jury on February 24.

The case had been news from coast to coast.

The case had been news from coast to coast.

Sneed’s trial ended with a hung jury.

Sneed’s trial ended with a hung jury.

By September 1912 Sneed was free on bond awaiting his second trial for killing A. G. Boyce Sr. Also by September A. G. Boyce Jr. had returned from Canada and was living with his mother in Amarillo. On September 14 John Beal Sneed, disguised and lying in wait with a shotgun, shot and killed Boyce Jr. as Boyce walked down a street in Amarillo. After shooting Boyce Jr., Sneed walked to the courthouse and surrendered.

John Beal Sneed now faced charges of murdering two A. G. Boyces.

John Beal Sneed now faced charges of murdering two A. G. Boyces.

Meanwhile, during Sneed’s second trial for killing Boyce Sr. (are you keeping this straight?), Wild Bill’s invocation of the unwritten law was apparent as he cross-examined the widow of Boyce Sr.

Present in the courtroom at the time was Lynn Boyce, another son of Boyce Sr.

The Star-Telegram wrote: “From the beginning of the cross-examination of his [Lynn Boyce’s] mother, whom he had tenderly assisted to the witness stand a half hour before, the big Westerner [Lynn Boyce] had showed restlessness, moving about in his chair and whittling nervously with a pearl-handled, long-bladed knife [in a courtroom!], a habit he has displayed through the whole trial. He sat in the corner of the courtroom, back of the jury, and only twelve feet from the attorney [McLean].

“McLean had asked Mrs. Boyce why they [Mr. and Mrs. Boyce Sr.] didn’t put Albert, her son, in a sanitarium, and she had replied that he was not a fit subject for a sanitarium.

“‘Don’t you think,’ the attorney [McLean] asked, ‘that a man who has run over and disgraced his father and mother, and is stealing another man’s wife, and killing his little children is a fit subject for a sanitarium or the penitentiary!’”

At this point Lynn Boyce overturned his chair as he sprang at McLean. Boyce was restrained by two men, ejected from the courtroom, and fined $100 and an hour in jail by the judge.

At this point Lynn Boyce overturned his chair as he sprang at McLean. Boyce was restrained by two men, ejected from the courtroom, and fined $100 and an hour in jail by the judge.

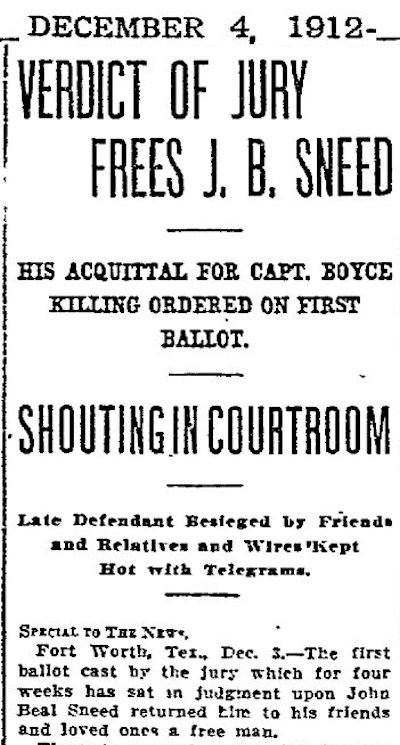

John Beal Sneed was acquitted of murdering A. G. Boyce Sr.

John Beal Sneed was acquitted of murdering A. G. Boyce Sr.

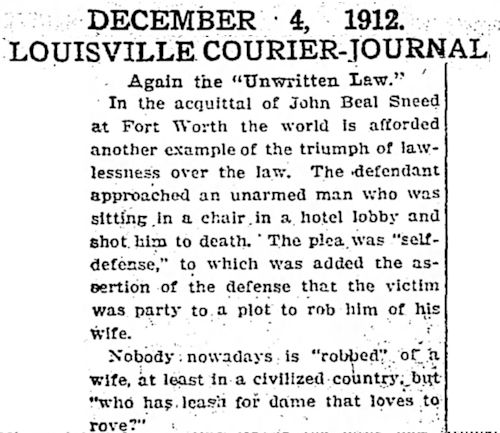

The verdict drew reactions around the country. The Louisville Courier Journal called the acquittal “the triumph of lawlessness over the law.”

The verdict drew reactions around the country. The Louisville Courier Journal called the acquittal “the triumph of lawlessness over the law.”

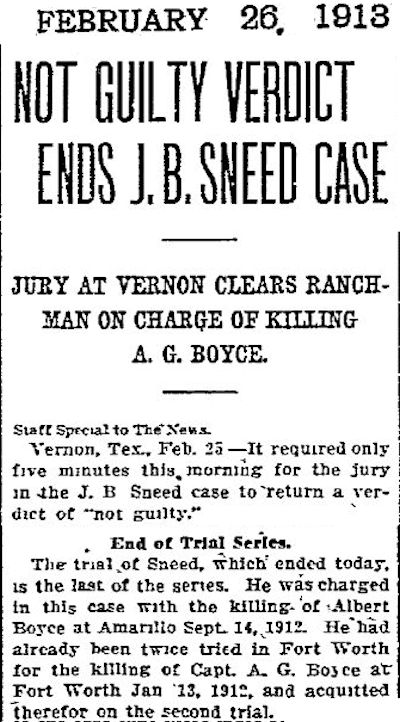

Fast-forward to January 1913. In Sneed’s trial for killing Boyce Jr., Wild Bill McLean again invoked the unwritten law, arguing that Sneed had been justified in killing Boyce Jr. because Sneed had feared that Boyce would elope with Lena Sneed again.

Associated Press wrote: “William P. McLean Jr. of the defense justified Sneed’s killing of Boyce without giving warning because, he [McLean] said, ‘he [Sneed] wouldn’t have had a chance in the open, and he could not bear to think of his two little children after he was dead living under the same roof with a man like Al Boyce, the despoiler of his home.’”

McLean told the jury: “Sneed is on trial for killing the man who crept into his home, debauched his wife, disgraced his children, and has more than murdered him. Let’s count the arrows that have been shot into the heart and the brain of Beal Sneed. . . . Mrs. Boyce [Al Boyce Jr.’s mother] herself said on the witness stand that she and Captain Boyce, Al’s own parents, could not keep Al away from Beal Sneed’s wife. There was but one thing to do, and that was to kill him. Were the penitentiaries made for such men as Beal? If they were, then I want to go to this penitentiary and associate with home protectors. Whenever a home is despoiled, gentlemen, I say there ought to be a killing.”

Wild Bill McLean and the unwritten law won again: John Beal Sneed was acquitted a second time.

Wild Bill McLean and the unwritten law won again: John Beal Sneed was acquitted a second time.

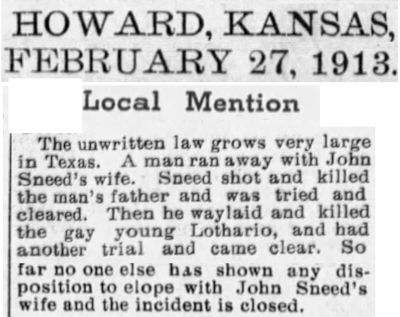

The newspaper in Howard, Kansas wrote: “The unwritten law grows very large in Texas.”

The newspaper in Howard, Kansas wrote: “The unwritten law grows very large in Texas.”

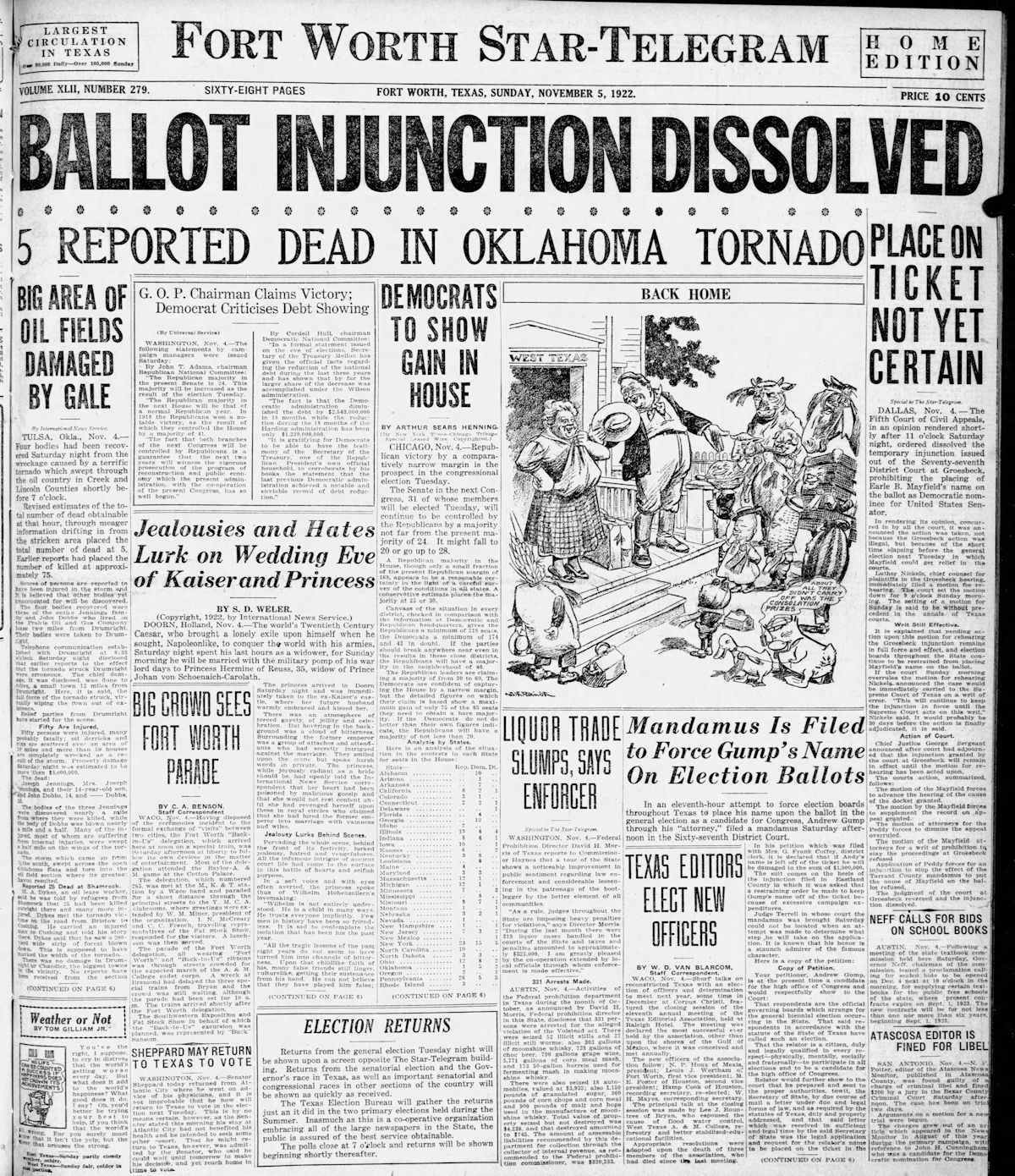

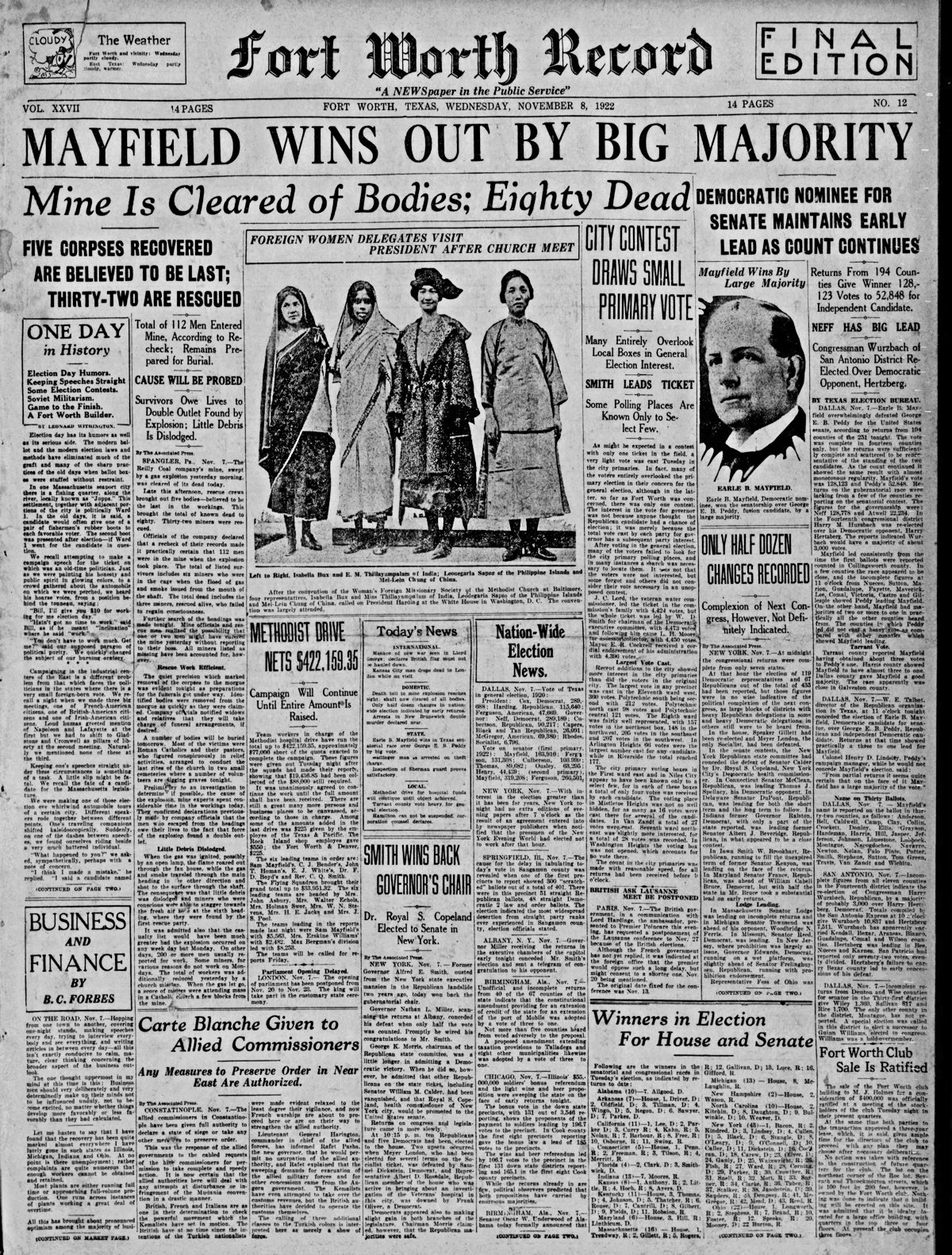

Fast-forward to 1922. When U.S. Senator Charles Allen Culberson of Texas ran for reelection, he was too ill to return to Texas to campaign. The Ku Klux Klan in Texas sensed that Culberson was vulnerable. The Klan was at its peak of influence in Texas in the early 1920s. In March 1922 four of the KKK’s most powerful men, including Brown Harwood of Fort Worth, met in Waco and decided to field three Klan-friendly candidates in the Democratic primary against Culberson. The Klan would endorse the candidate who made the best showing.

That candidate was Earle B. Mayfield, who was state railroad commissioner and a former state senator. Mayfield claimed publically that he had relinquished his Klan membership just before he entered the primary race against Culberson. But Mayfield admitted that he continued to attend Klan meetings and was backed by the Klan.

Some Democrats in Texas—many of them anti-Klan—challenged Mayfield’s right to be on the ballot because of alleged irregularities in his campaign finances. These Democrats went to court and got an injunction forbidding Mayfield’s name from being placed on ballots. Mayfield hired Wild Bill McLean to challenge the injunction.

McLean was successful, Mayfield’s name appeared on the ballot, and a Klandidate went to Washington.

McLean was successful, Mayfield’s name appeared on the ballot, and a Klandidate went to Washington.

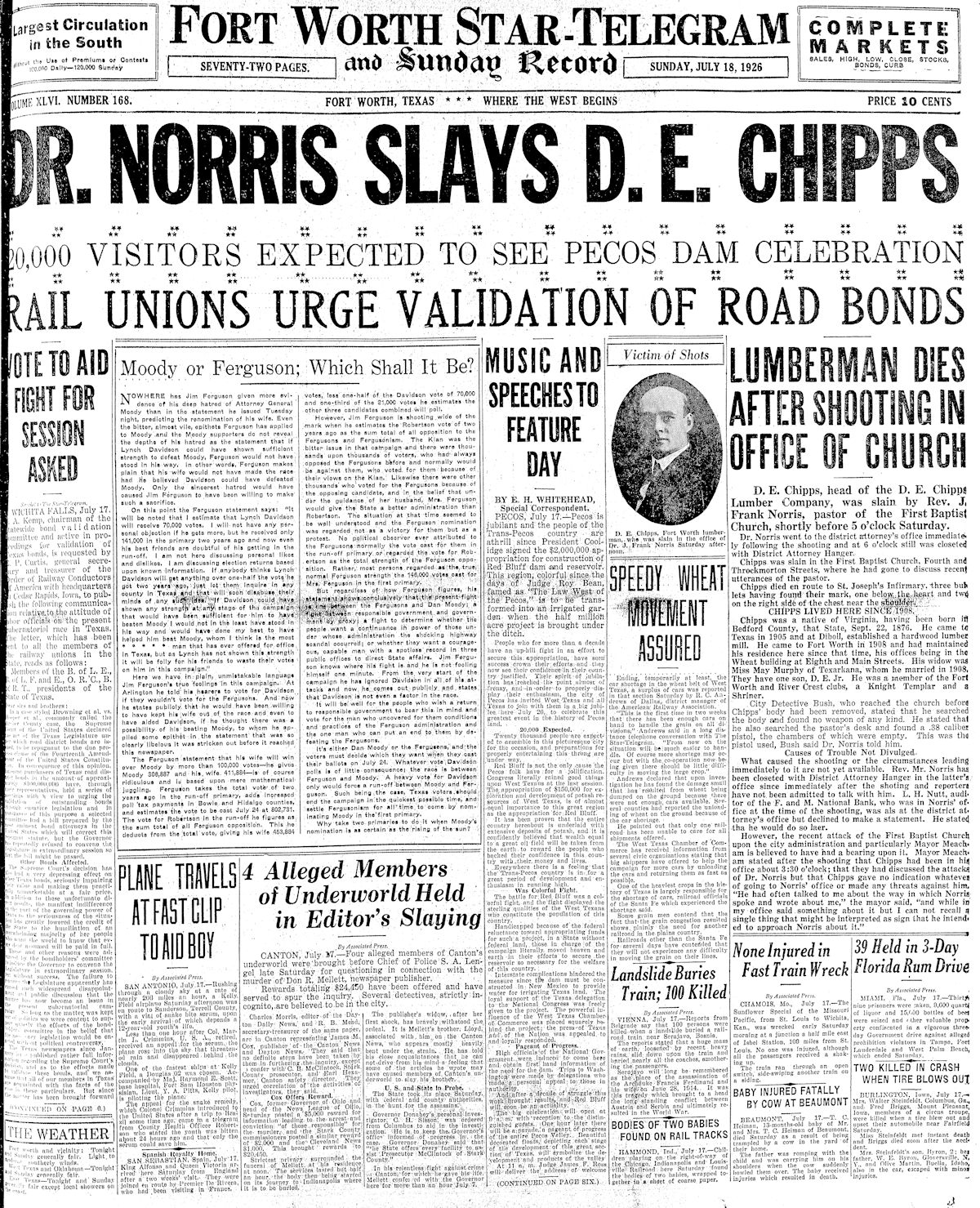

Fast-forward to 1926 and another sensational murder case. But this time Wild Bill McLean the criminal defense attorney was Wild Bill McLean the special prosecutor.

J. Frank Norris, pastor of First Baptist Church, and Henry Clay Meacham, mayor and department store owner, were two of the most prominent men in town.

And two of the most publically at odds.

Norris, a Baptist, was anti-Catholic and said the Meacham city administration was “morally corrupt” because Meacham had “known Roman Catholic associations.”

In 1926 Norris preached a sermon against Meacham, accusing the mayor of misappropriating city funds for Catholic causes. Norris drafted a small army of boys to surround Meacham’s department store and hand out to shoppers copies of Norris’s Searchlight newsletter containing the text of the anti-Meacham sermon.

On July 17 wholesale lumberman Dexter Elliott Chipps, a friend of Meacham, left the Westbrook Hotel and walked eight blocks to First Baptist Church.

People who saw Chipps at the hotel and in the church building said later he appeared to be drunk. At the church Chipps asked where he could find Reverend Norris.

In the pastor’s study, Chipps was told.

A few minutes later Dexter Elliott Chipps was dead, shot three times by Norris.

Norris later made a statement to police: “I had a telephone call today. It was fifteen or twenty minutes before the trouble [shooting]. The first words that were spoken when I said ‘hello’ were ‘We are coming up there and settle with you.’ I asked, ‘Who is this,’ and the voice on the phone came back with ‘Don’t matter, you G— — — —.’ I asked for his name. He told me. I first thought he said Litts or Hitts and then he said Chipps.

Norris later made a statement to police: “I had a telephone call today. It was fifteen or twenty minutes before the trouble [shooting]. The first words that were spoken when I said ‘hello’ were ‘We are coming up there and settle with you.’ I asked, ‘Who is this,’ and the voice on the phone came back with ‘Don’t matter, you G— — — —.’ I asked for his name. He told me. I first thought he said Litts or Hitts and then he said Chipps.

“I told him that surely he did not mean what he had just said. But he answered back, ‘Well, I’m coming up there.’ I insisted that he not come. I didn’t want any trouble with him. But he again threatened me and said he was corning to my office, declaring that he ‘wouldn’t stand it any longer.’

“I walked to my stenographer’s office after hanging up the telephone. I got some sermon notes and came back to get matters ready for the Sunday school superintendent’s work for Sunday.

“Soon Mr. Chipps came into my office. He did not knock. He came busting in. He was very angry. He talked that way, and I could see he was mad.”

Norris quoted Chipps: “I am going to kill you for what you said in your sermons, damn you.”

Norris said that Chipps was referring to statements about Meacham that Norris had made in his recent sermons and in his Searchlight newsletter.

L. H. Nutt, a deacon of the church, was in the study with Norris when Chipps entered. Nutt later confirmed that Chipps threatened Norris.

Norris told police: “I remonstrated with him and told him I did not want to have any trouble. I walked to the door of my office and invited him to leave, and as I turned and walked back to the desk he followed me and continued to threaten to kill me.”

Norris told police: “‘I mean every word I have told you,’ he [Chipps] said as he threw his hand behind him. There was a gun in the desk which the night watchman used. I reached in and got it. I saw nothing else for me to do but defend myself. He repeated his statement to me again, continuing to threaten me. I’m sorry I had it to do. I thought my life was in danger, and I shot him.”

Police searched Chipps’s body and Norris’s study.

Police detective C. D. Bush said, “I could not find any pistol or any weapon on his [Chipps’s] person. He had not been moved before I searched him. I found no pistol in the room except the one used in the shooting, and it was empty. Someone had removed the empty shells.”

Norris was charged with murder.

Meacham paid $15,000 ($215,000 today) to Will Bill McLean’s law firm to act as special prosecutors at Norris’s murder trial because, Meacham said, “Elliott Chipps would have done as much for me if the circumstances would have been reversed.”

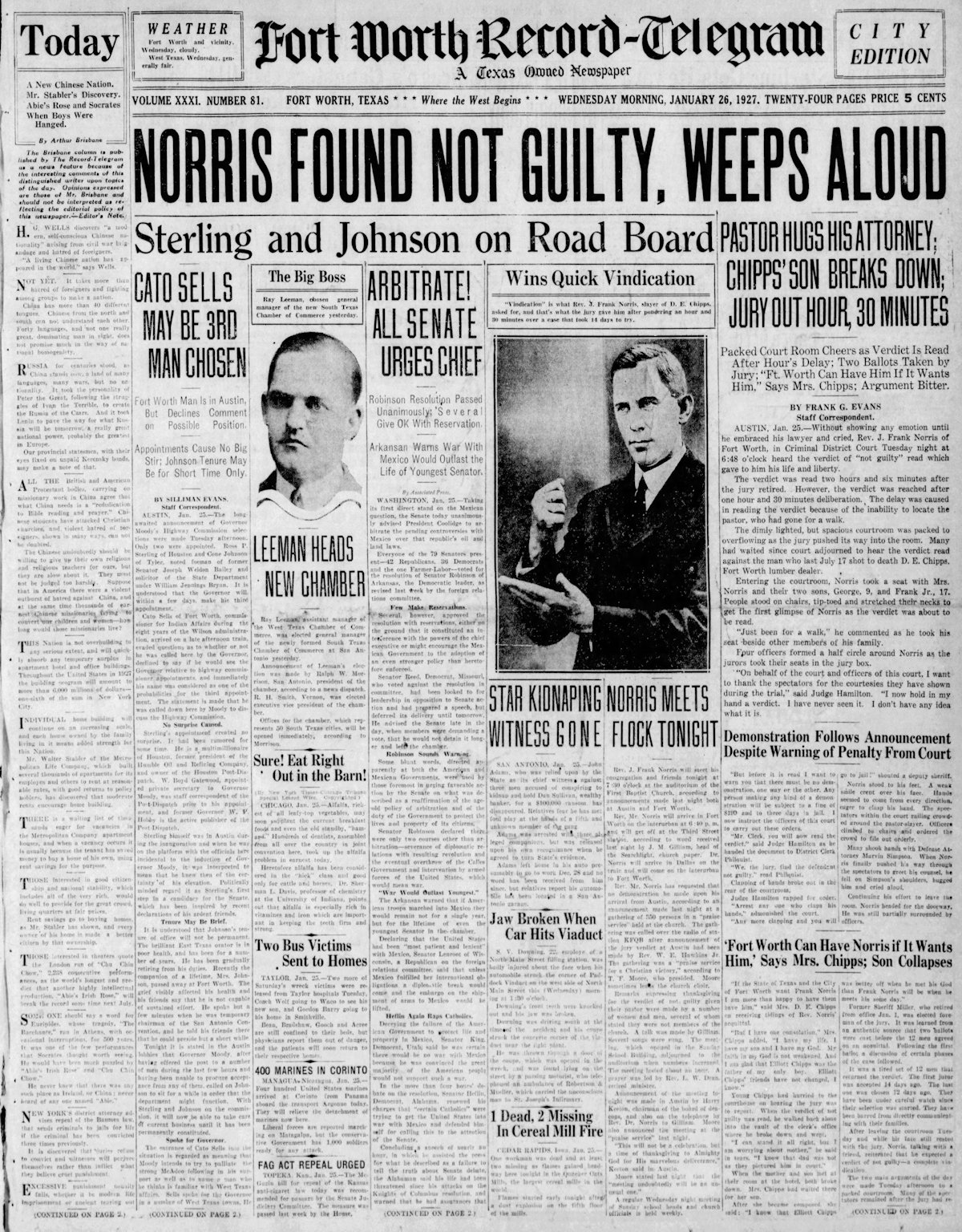

Testimony in the murder trial of J. Frank Norris began in Austin on January 14, 1927. In the front page photo, Norris is circled in red, the widow Chipps in yellow, and McLean in blue.

Testimony in the murder trial of J. Frank Norris began in Austin on January 14, 1927. In the front page photo, Norris is circled in red, the widow Chipps in yellow, and McLean in blue.

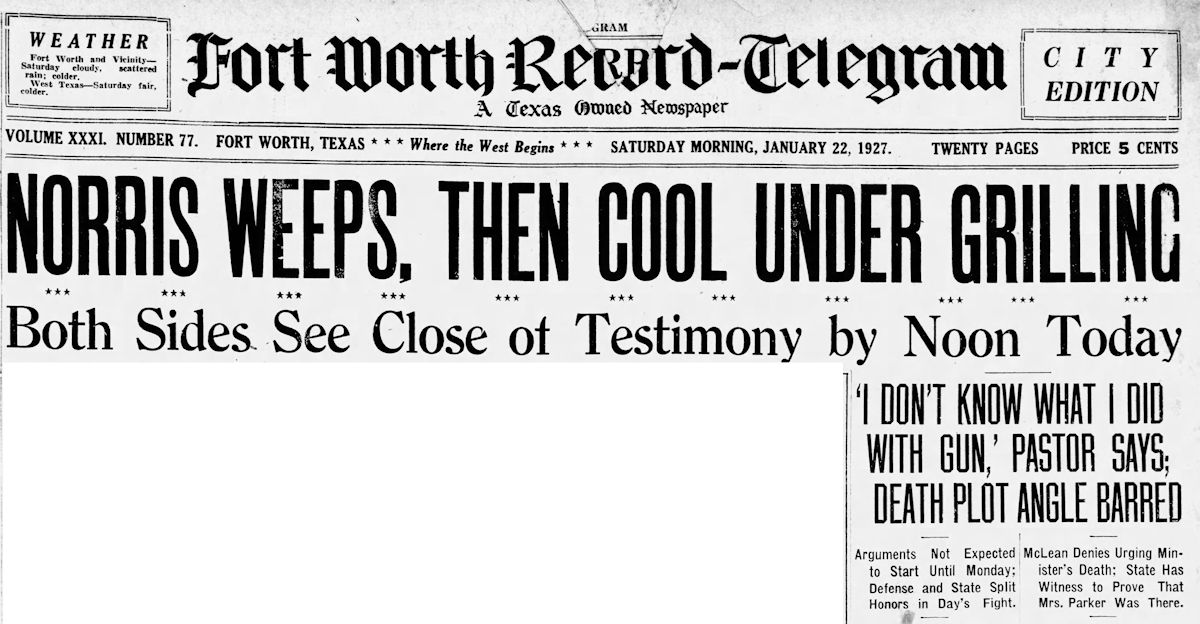

On January 21 special prosecutor McLean found himself on the defensive. Norris’s defense attorneys claimed that Henry Clay Meacham and Chipps had conspired to kill Norris. Away from the jury, attorneys for Norris and the state discussed the admissibility of testimony alleging such a conspiracy. Defense attorney Dayton Moses brought up the rumor that Wild Bill McLean himself had once told Meacham that Meacham should kill Norris for saying the things he had said about Meacham.

McLean responded to Moses: “I want to say here right now before Norris murders me that he can not plead that I had threatened to kill him or advised that he be killed. If any witness does swear to it, it will be telling an infamous lie.”

Also on January 21 Norris took the witness stand, where he wept as he recalled the shooting of Chipps. Later Norris was cross-examined by McLean.

Also on January 21 Norris took the witness stand, where he wept as he recalled the shooting of Chipps. Later Norris was cross-examined by McLean.

The Star-Telegram wrote: “Rev. Mr. Norris went through the ordeal of a merciless cross-examination at the hands of McLean. Question after question was relentlessly plied at the defendant by McLean. The pastor kept his eyes fixed upon the prosecutor and answered every question in a slow, deliberate voice.

“McLean’s voice twanged with the sting of a trained prosecutor at every moment of the grilling.

“‘Where did you unload that six-shooter with which you shot Chipps?’ McLean asked him [Norris] as he [McLean] kept shifting suddenly from one angle of the case to another.

“‘I don’t know,’ the pastor replied. Rev. Mr. Norris was leaning back in the witness chair with arms folded. His eyes were red from the tears shed at the morning session.

“‘What was your purpose in unloading that pistol?’ McLean asked with a voice that rang like the bite of sharp steel.

“‘I have never known why,’ Rev. Mr. Norris answered. His tone had never changed up to this point.”

McLean: What kind of pistol did you shoot him with?

Norris: Just an ordinary pistol, I suppose you would say.

McLean: Later you found the shells in your pocket?

Norris: Yes, four empty shells and one loaded. They were .38 calibers.

McLean: What did you do with them?

Norris: Threw them away.

McLean: When did you find them in your coat pocket?

Norris: About three or four weeks later.

McLean: Where were you when you threw away the empty shells?

Norris: Sitting on my back porch.

“McLean suddenly shifted his line of questions again,” the Star-Telegram wrote.

“‘After the telephone conversation with Chipps, you did not call for officers either at the police station or at the sheriff’s office?’ he asked.

“‘No,’ Rev. Mr. Norris replied.

“‘Isn’t it a fact,’ McLean began, ‘that when you shot Chipps that he exclaimed, “Oh, you oughn’t have done it”?’

“‘No, sir,’ replied Rev. Mr. Norris.”

Norris also denied a claim made by a witness for the state that just after the shooting Norris said, “I have killed me a man.”

On January 25 Wild Bill McLean presented the closing argument for the prosecution. Many Texas newspapers, including the Waco News-Tribune, printed his words verbatim. Some excerpts:

On January 25 Wild Bill McLean presented the closing argument for the prosecution. Many Texas newspapers, including the Waco News-Tribune, printed his words verbatim. Some excerpts:

“Thank God that our forefathers, the Constitution of the United States, and the Constitution of Texas, which my father helped write, that no man should be tried without being tried before a court and before twelve jurors. That is correct. No man wants that law taken away from us, sir.”

“Chipps threatened Norris’s life, . . . so Norris said. How was Chipps tried? Norris was the judge, Norris was the jury and Norris was the executioner. That is the trial that poor old Chipps got.”

McLean scoffed at the theory that Mayor Meacham had sent Dexter Chipps to kill Norris: “The city fathers elected him mayor to run our town. Now, if he was going to harm Norris, or anybody else, would he have gotten him a drunken man to have done it? That is absurd and ridiculous.”

McLean reminded the jury that Chipps, in addition to threatening Norris directly by phone on the day of the shooting, on the day before the shooting had told a police officer that he was going to kill Norris. Norris was warned of that previous threat but, McLean pointed out, did not notify police even after the telephone threat because, McLean said, Norris wanted Chipps to come to the church so that Norris could kill him and be able to use Chipps’s threats to claim self-defense.

McLean ended his speech to the jury by expressing skepticism of Norris’s tears as Norris had testified that he had not wanted to kill Chipps. McLean’s final words to the jury were an ominous prediction:

“If I don’t do your [Norris’s] bidding, by the lash of your tongue, by the wires of your radio or by the circulation of your newspaper, you can destroy my character, and I know if I go to talk to you you will take my life.

“That is the man you are trying, and in conclusion I want to say that if a man had come into my office or if a man had gone into your office or into your home, after threatening your life, calling you that lowdown name and gone in there and cursed you out and you believed he was there, going to kill you, and you had shot him down, you never would shed a tear in there, neither would I.

“Talk about your actors, gentlemen of the jury. Oh, these movie picture stars never equaled Norris. Perfect control; then he commences crying and sobbing before this jury, the sighs of hypocrisy, begging men to acquit him and when you shall have done it, and when he goes back to his infamous slandering of good people, and when you pick up the paper and see this time he didn’t kill a poor unfortunate drunk, but that he snuffed the life out of a better man, [pointing a finger at the jury] he is your criminal, not mine.”

But Wild Bill McLean’s fiery rhetoric and J. Frank Norris’s smoking gun were not enough to convince the jury. Norris was acquitted. The next day he attended a “praise service for a Christian victory” at his church.

But Wild Bill McLean’s fiery rhetoric and J. Frank Norris’s smoking gun were not enough to convince the jury. Norris was acquitted. The next day he attended a “praise service for a Christian victory” at his church.

Fast-forward to 1930. The widow of Sam Houston’s son Temple sued Liberty Magazine, claiming that the magazine’s profile of Sam libeled son Temple by claiming that Temple was born of an “aboriginal marriage with an Indian woman” and that Temple was “a wild one” and a “dangerous citizen of Oklahoma.”

Fast-forward to 1930. The widow of Sam Houston’s son Temple sued Liberty Magazine, claiming that the magazine’s profile of Sam libeled son Temple by claiming that Temple was born of an “aboriginal marriage with an Indian woman” and that Temple was “a wild one” and a “dangerous citizen of Oklahoma.”

Arguing the suit for Mrs. Houston were Wild Bill McLean and Leroy A. Smith. Liberty Magazine’s defense attorney was Sidney Samuels of Fort Worth.

Opening arguments by McLean and Smith revealed their strategy to focus on the alleged libel contained in references to Temple Houston’s birth. The two attorneys claimed that the reference to an “aboriginal marriage” implied illegitimacy and thus stained the “grand old name of Houston.”

McLean said: “You could go into any school in Fort Worth or any school in Texas and every child would tell you who was the mother of Temple Houston and the wife of Gen. Sam Houston. The time has come for every Texan who reveres the dead to put a stop to the slander against the state’s heroes. But for Gen. Sam Houston we might have been a part of Mexico today, and but for the efforts of the son, who carried on after the death of his illustrious father, we might also have been a part of Mexico.”

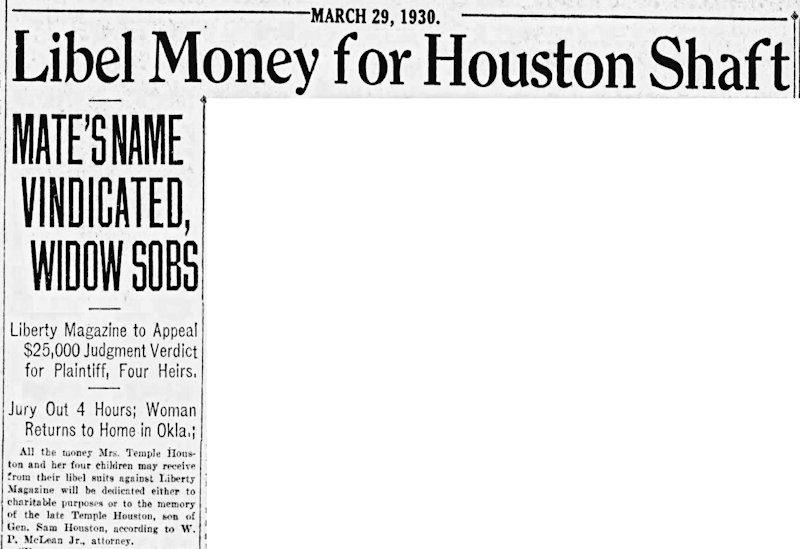

Mrs. Houston was awarded $25,000 ($400,000 today). The Record-Telegram wrote: “All the money Mrs. Temple Houston and her four children may receive from their libel suits against Liberty Magazine will be dedicated either to charitable purposes or to the memory of the late Temple Houston, son of Gen. Sam Houston, according to W. P. McLean Jr., attorney.”

Mrs. Houston was awarded $25,000 ($400,000 today). The Record-Telegram wrote: “All the money Mrs. Temple Houston and her four children may receive from their libel suits against Liberty Magazine will be dedicated either to charitable purposes or to the memory of the late Temple Houston, son of Gen. Sam Houston, according to W. P. McLean Jr., attorney.”

McLean added: “You can say the same thing for all the money McLean, Scott and Sayers receive as fees in representing the plaintiffs.”

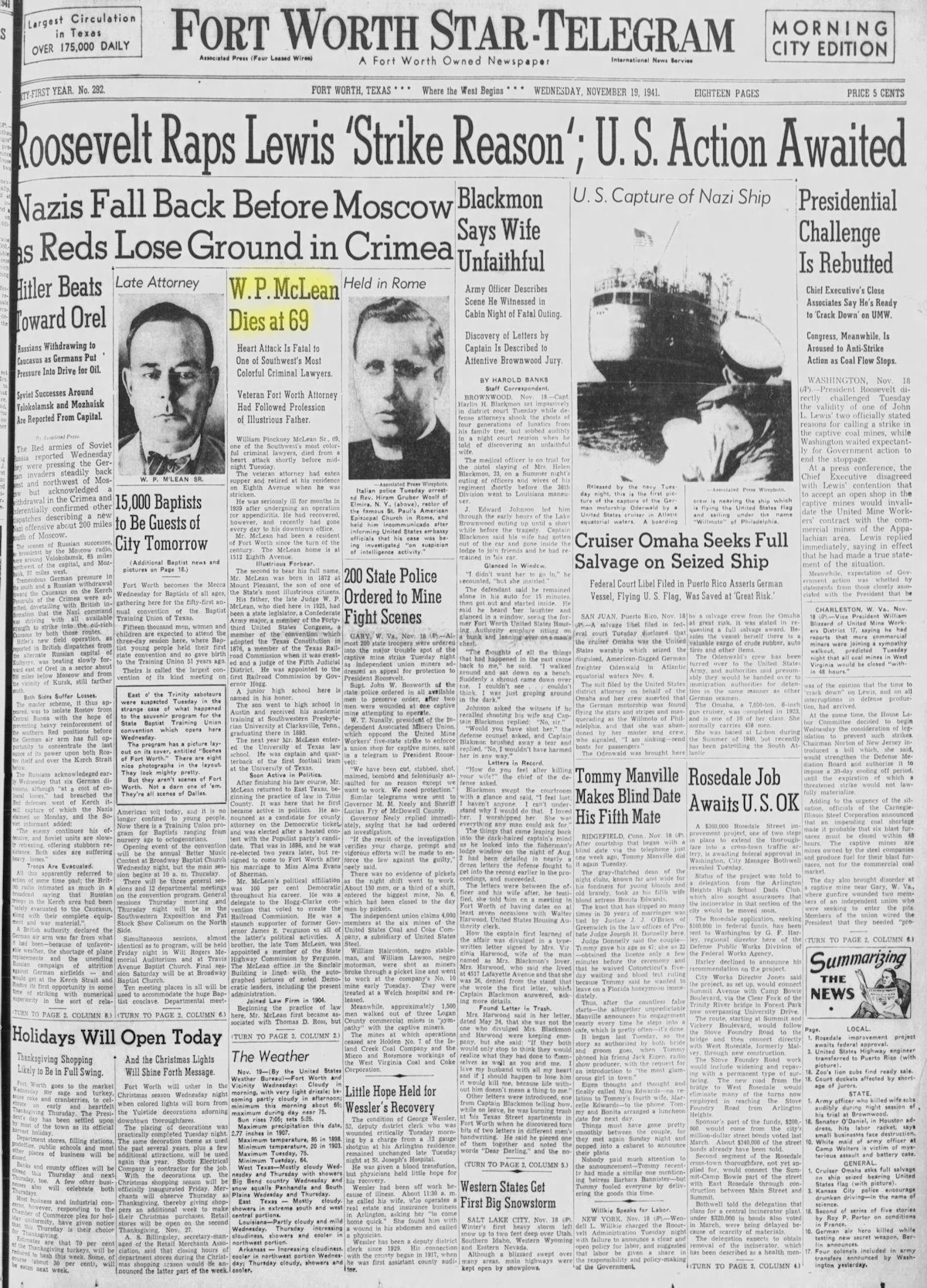

William Pinckney McLean Jr. died on November 18, 1941. He was sixty-nine years old. The Star-Telegram wrote, “Mr. McLean’s firm, during the last thirty-five years, has freed seventy-three defendants charged with murder.”

William Pinckney McLean Jr. died on November 18, 1941. He was sixty-nine years old. The Star-Telegram wrote, “Mr. McLean’s firm, during the last thirty-five years, has freed seventy-three defendants charged with murder.”

Wild Bill McLean is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

Wild Bill McLean is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade