This is a grave in Laurel Land Cemetery. Vincent Harold McClure was eleven years old.

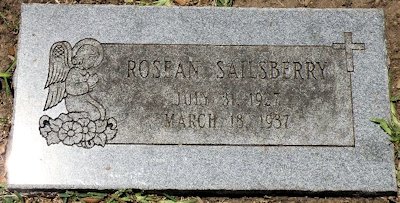

This is a grave in Greenwood Cemetery. Rosean Sailsberry was twelve years old.

This is a grave in Greenwood Cemetery. Rosean Sailsberry was twelve years old.

Note that both children died on the same date: March 18, 1937.

Coincidence?

No.

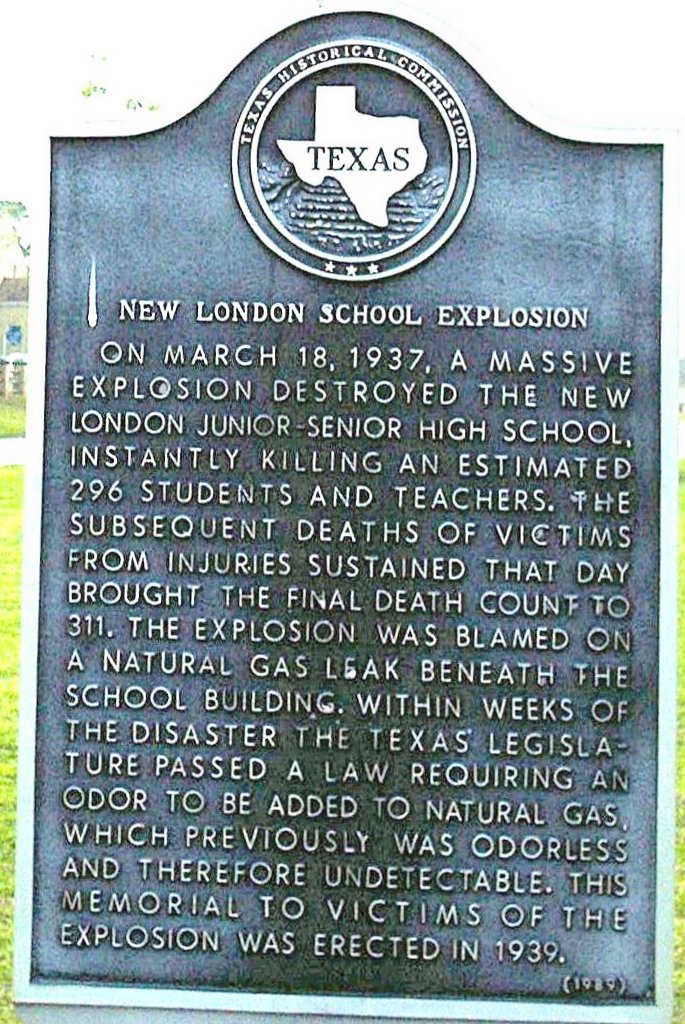

Vincent and Rosean were two of an estimated 311 people who died in the New London school explosion—the deadliest school disaster in American history.

The Setting

The town of New London is located in Rusk County 150 miles southeast of Fort Worth and nine miles northwest of the county seat of Henderson.

The town of New London is located in Rusk County 150 miles southeast of Fort Worth and nine miles northwest of the county seat of Henderson.

In the 1930s Rusk County was oil country.

In the 1930s Rusk County was oil country.

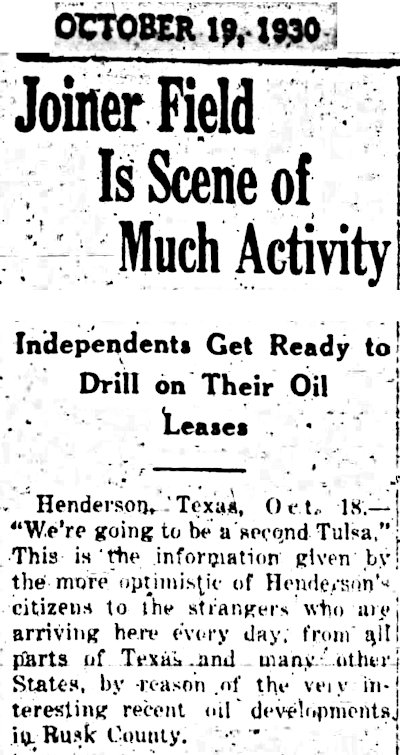

At 8 p.m. on October 3, 1930 seventy-year-old wildcatter Columbus Marion Joiner brought in a gusher on the farm of Daisy Bradford.

And that changed everything.

Soon residents of Henderson were predicting that their town would become the “second Tulsa.” (Tulsa was known as the “oil capital of the world.”)

With Joiner’s discovery, suddenly east Texas boomed just as west Texas had boomed in 1917 after William Knox Gordon brought in a gusher on the McCleskey farm near Ranger.

With Joiner’s discovery, suddenly east Texas boomed just as west Texas had boomed in 1917 after William Knox Gordon brought in a gusher on the McCleskey farm near Ranger.

Oil derricks soon became the skyline of Rusk County.

People got rich. Towns boomed. The town of New London was located just three miles north of the Joiner well. In less than three years the town population grew from two hundred to three thousand.

People got rich. Towns boomed. The town of New London was located just three miles north of the Joiner well. In less than three years the town population grew from two hundred to three thousand.

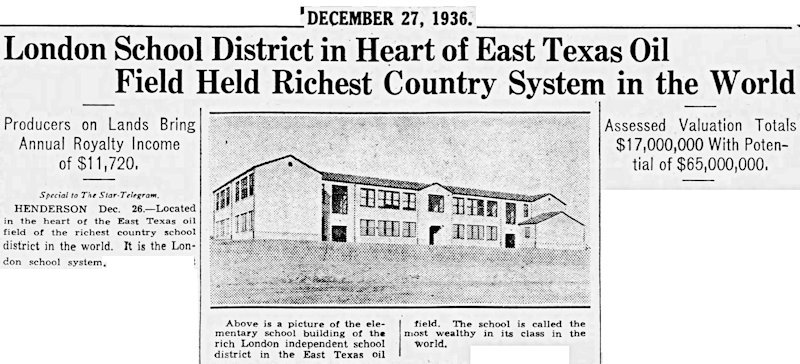

School districts also got rich. But none got richer than the London school district. The Joiner well was located in the school district, which covered thirty square miles of oil country. The London school district was soon known as the richest rural district in America. The taxable property in the district was valued at $17 million ($322 million today). There were fifteen producing oil wells on the district’s own land, bringing in $12,000 ($200,000 today) a year.

In 1930 the London school was a wooden structure housing one hundred students. After oil was discovered, in 1932 the London school district paid cash for a new school building for elementary through high school students. The new school had an enrollment of twelve hundred, many of them the children of oil workers who had moved into the area during the boom.

The school’s ten-acre campus had seven producing oil wells.

The flush London school district paid $1 million ($19 million today) for the new school.

And indeed the school was state-of-the-art. The main building, which housed grades five through eleven, was 253 feet long. Its walls were made of brick and hollow tile blocks, its frame of steel. The main building had twenty classrooms, two laboratories, two study halls and libraries, an auditorium seating 650, offices for the principal and superintendent, book rooms, supply rooms, and music studios.

The home economics building was equipped with food and clothing laboratories, living room, dining room, and a bedroom.

The gymnasium had a seating capacity of 750 and housed basketball, volleyball, and tennis courts.

The school’s commercial department featured the latest in business machines: comptometers, ediphones (sound recording devices), calculating machines, adding machines, a mimeograph machine, and type pacers (pacers for typing students).

There were laboratories for chemistry, biology, general science, and physics.

The school band had sixty-five instruments.

For the youngest students there were playhouses, including a simulated log cabin.

The athletic field was one of the first in the state to be lighted.

The school had nine buses.

But, the Star-Telegram wrote, “The pride of the school is the manual training department, which includes a workshop equipped with all sorts of mechanical devices.”

One of those mechanical devices was an electric sander.

The school district was well aware of where its wealth came from. The London school’s mascot was the Wildcat (a play on the term wildcatter, meaning “oil prospector”).

Yes, the London school district had plenty of money, but perhaps because the school board was so accustomed to being poor and cutting corners, in early 1937 the school board, to save a $300 ($5,500 today) monthly natural gas bill, canceled its natural gas contract and had plumbers tap into Parade Gasoline Company’s residue gas pipe.

Such tapping was not an uncommon practice. The process of extracting oil also extracted natural gas as a residue. This residue gas was considered to be a waste product and normally was burned off by flares. Because oil companies did not value residue gas, they did not complain when it was tapped by entities such as the London school district.

Likewise, to heat the school’s main building the school board had rejected the architect’s plans for a boiler-and-steam system, instead installing seventy-two natural gas heaters. Each heater burned natural gas to heat water to produce steam in a radiator.

The Prelude

Then came March 18, 1937. It was a Thursday. There would be no school the next day so that students could attend an interscholastic competition in Henderson.

By 3:17 p.m. the school’s elementary students had been dismissed to begin their three-day weekend.

By 3:17 p.m. some parents were attending a PTA meeting in the gymnasium building, located one hundred feet from the main building. At the same time, some teachers were attending a faculty meeting in the gymnasium building.

By 3:17 p.m. only thirteen minutes remained until dismissal time. About six hundred people were in the main building at the time.

Many of the students and teachers were attending an assembly in the auditorium.

The Explosion

At 3:17 p.m. shop teacher L. R. (“Lemmie”) Butler, twenty-nine, was in his classroom with his students.

W. G. (“Bud”) Watson was an eighth-grader in that class. Years later Watson recalled: “I was in shop class, which was on the first floor, with about thirty other boys. It was getting close to quitting time, and I was doing some welding in the front of the room when our teacher, Lemmie Butler, must have pulled an electrical switch to get a machine to work. Next thing I knew, I was picking myself up outside of the building. I don’t remember flying out the window, but the building was still coming down.”

The New London school building had exploded.

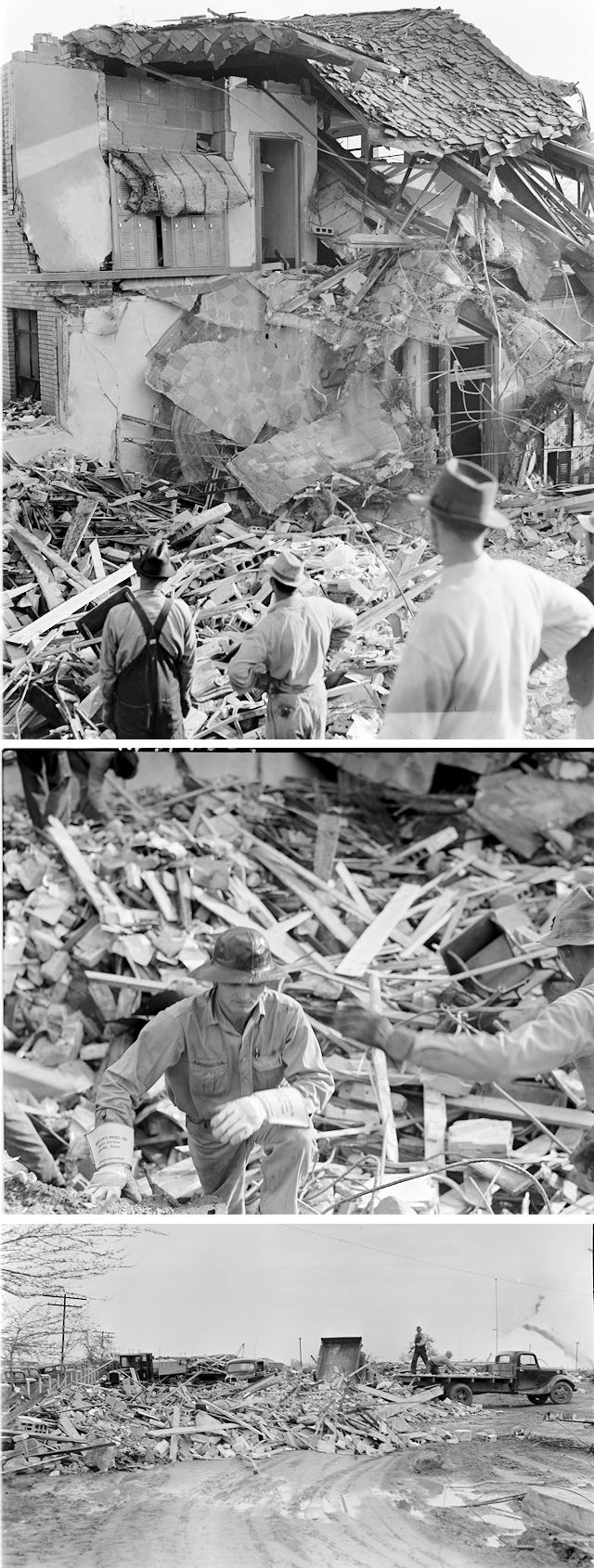

With a deafening roar, the earth shook, the exterior walls of the school bulged outward and collapsed, and the concrete floors and the roof were propelled upward and then fell, pancaking onto the occupants of the building. Students and teachers were crushed by falling rubble, hit by flying debris, hurled across rooms and even hurled free of the building by the explosion.

Pulverized brick and hollow tile blocks and concrete and plaster created a fog of dust that was rendered into hot mud as steam from ruptured radiators swept over the building, scalding people who were already injured.

Only one corner of the building remained standing.

Four measures of the force of the explosion:

A two-ton chunk of concrete was thrown clear of the building and crushed a car parked two hundred feet away.

School lockers were thrown a half-mile.

A man standing a half-mile from the school saw bricks fly by.

Residents who lived four miles away heard the explosion, although they were not alarmed at first because such booms often were heard from the oil fields, where explosives were used.

In the rubble of the school building the dead and injured lay scattered about, some in plain sight, some covered in rubble. Amid the cynical hiss of ruptured radiators came the cries and moans of the injured.

“Greatest Mineral Blessings”

The first people to reach the rubble were parents and teachers who had been attending meetings in the gymnasium building. As the gymnasium shook, parents and teachers—mostly women—rushed outside from a tranquil world of treasurer’s reports and parliamentarians to a horrific world of death and suffering. Those parents whose children were students in the main building screamed their children’s names as they surveyed mutilated bodies strewn across the rubble and, fearing the worst, ran from bloody face to bloody face. Some parents became sick but fought back their shock and revulsion and ran to tend the fallen bodies, to any movement or human sound in the rubble, and began digging with their bare hands to free the buried. Others ran to telephones to call for help.

The PTA members and teachers were quickly joined by nearby residents.

The few victims of the explosion who were uninjured rose from the dust and staggered to join in the rescue effort, digging to uncover classmates and teachers.

News of the disaster spread by word-of-mouth and telephone and radio.

In northwest Rusk County in 1937 almost every family had a student at the school, knew a student at the school, or knew a parent of a student. March 18 made everyone a neighbor as people rushed to the scene to help.

Rusk County in 1937, remember, was oil country. Major oil companies, such as Humble and Gulf, dispatched roughnecks (oil field workers), trucks, motorized cranes, and tractors to clear the rubble and acetylene torches to cut away the building’s twisted steel skeleton.

Oil field work was dangerous. Fatal injuries were not uncommon, but on March 18 hardened roughnecks looked upon the wholesale slaughter of the innocent by the very resource that had made the London school district the richest rural district in America.

R. K. Carr, an oil company worker, was one of the first rescuers to reach the scene. The first body he found was that of his daughter.

For some of the men, veterans of World War I, it was the horror of combat all over.

An oil roustabout from England said, “I went through four years of war. This is the first time I saw anything that was worse.”

Reverend C. W. Holmes, pastor of First Baptist Church in the nearby town of Overton, said, “I have never seen anything like it since I came out of the trenches of France.”

George M. Davidson, another oil field worker, two days earlier had dreamed about tragedy. The next morning he told his crew members about the dream. He was reminded that it is unlucky to tell of bad dreams before breakfast.

After the explosion he found the bodies of his three children in a makeshift morgue.

At the state level, Governor James Allred declared martial law in New London and dispatched National Guard troops, Texas Rangers, and Department of Public Safety highway patrolmen to assist local law enforcement personnel.

At the national level, President Roosevelt ordered the Red Cross and government agencies to “render every assistance in their power to the community to which this shocking tragedy has come.”

The Star-Telegram and Fort Worth Chamber of Commerce chartered a Braniff airliner to fly medical supplies to the scene.

Among the Fort Worth physicians who went to New London to help was Val D. Scroggie.

Amateur radio operators and the Kilgore radio station broadcast messages for anxious relatives.

Airmen were dispatched from Barksdale Field in Louisiana.

Within hours fifteen hundred rescue workers—roughnecks, nuns, nurses, doctors, Red Cross and Salvation Army workers, firemen, police officers, residents—were on the scene as ten-ton tractors dragged away chunks of concrete and crews cut away the steel frame with acetylene torches.

Rescue workers covered dead bodies with sheets and lined them up—one hundred here, forty there—to be taken to makeshift morgues. Anxious relatives moved along the lines of bodies, lifting sheets, crying out in inconsolable grief.

The school campus resembled a battlefield. Buildings on the campus that had been spared became a temporary infirmary, a morgue, and the headquarters for the National Guard. In ambulances, school buses, private vehicles, fire engines, and delivery trucks victims were rushed to churches and stores and even a skating rink that served as temporary triage and first aid stations, hospitals, and morgues. National Guard troops, accompanied by local Eagle Scouts, patrolled the area.

In Overton the pews of the First Baptist Church were pushed back to the walls, and cots and mattresses were spread on the floor for the wounded.

Residents stripped their beds of mattresses, sheets, and blankets for the makeshift hospital.

Members of the American Legion formed a human wall to keep distraught parents outside the church as doctors inside worked to save lives.

Residents of the New London area opened their homes to weary rescue workers, health-care workers, and people from out of town who had come to look for relatives.

Rescuers worked through the night. The disaster scene was illuminated by floodlights brought in from Beaumont, lights of the nearby athletic field, and natural-gas flare pipes.

Early in the morning of March 19 a cold rain began to fall, turning the rubble dust to mud. Rescuers, stripped to the waist, worked on with winches, tractors, cutting torches, shovels, bloody bare hands.

Found in the rubble was a classroom blackboard. Written on the blackboard was this reminder: “Oil and natural gas are East Texas’ greatest mineral blessings. Without them this school would not be here and none of us would be here learning our lessons.”

News reporters covered the disaster as they would a battle. Among the reporters dispatched to New London was a twenty-year-old United Press reporter covering his first national story: Walter Cronkite.

Cronkite later wrote, “I did nothing in my studies nor in my life to prepare me for a story of the magnitude of that New London tragedy, nor has any story since that awful day equaled it.”

Future White House correspondent Sarah McClendon was a reporter for the Tyler Courier-Times. She was one of the first reporters on the scene.

“I’ll never forget seeing the bones of a little girl, picked as clean as a whistle, clean as if they had been boiled,” McClendon recalled. “She was probably never identified. The blast literally tore the flesh from her bones.”

Scenes of the rubble. (Photos from Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.)

Scenes of the rubble. (Photos from Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.)

A soup line for rescue workers. (Photo from Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.)

A soup line for rescue workers. (Photo from Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.)

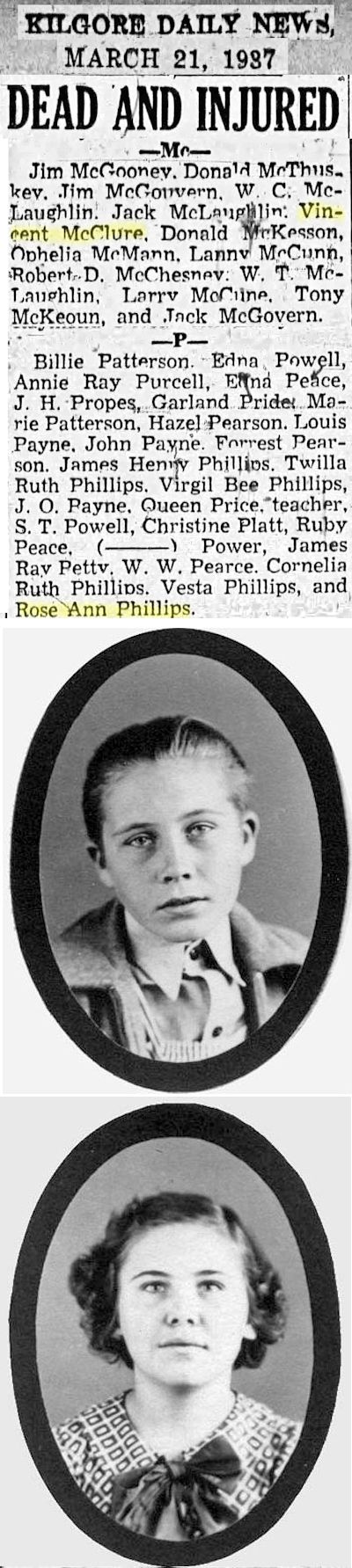

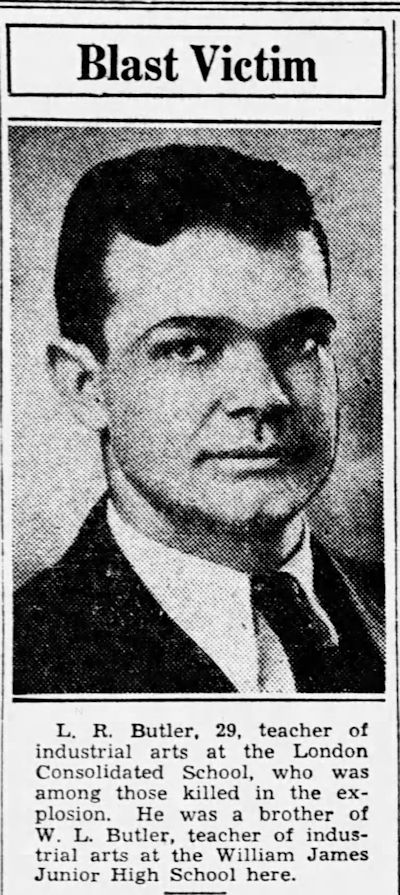

Newspapers printed lists of the dead and injured. Vincent Harold McClure and Rosean Sailsberry had lived in Fort Worth before their families moved to Rusk County. Rosean Sailsberry was listed in the Kilgore newspaper by her stepfather’s surname (Phillips). Her older sisters Isabell and Ernestine survived the explosion. (Photos from Find a Grave.)

Newspapers printed lists of the dead and injured. Vincent Harold McClure and Rosean Sailsberry had lived in Fort Worth before their families moved to Rusk County. Rosean Sailsberry was listed in the Kilgore newspaper by her stepfather’s surname (Phillips). Her older sisters Isabell and Ernestine survived the explosion. (Photos from Find a Grave.)

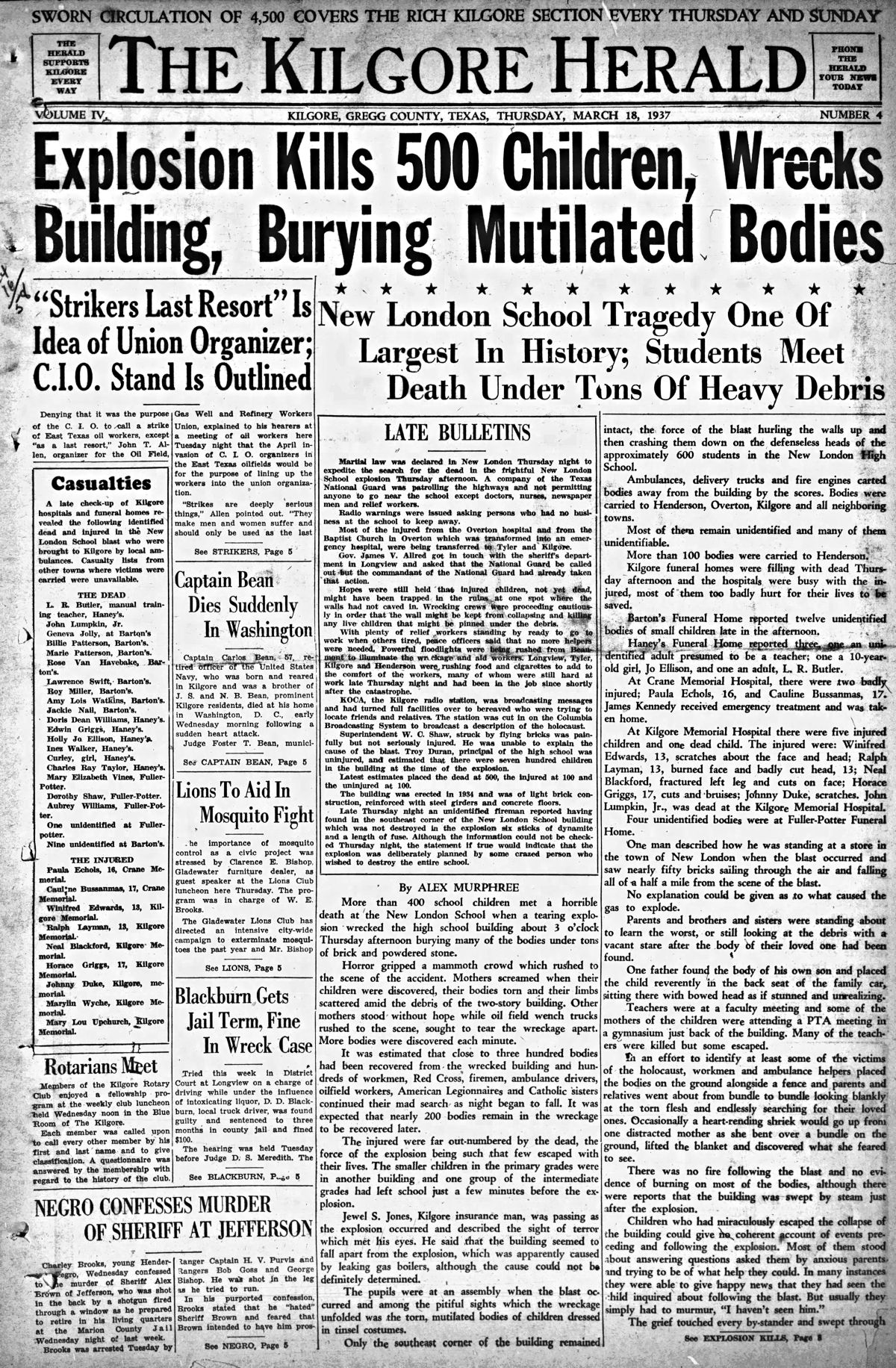

Among the fatalities was shop teacher Lemmie Butler. His brother William Ligon Butler taught shop at William James Junior High School and later was principal of Forest Oak Junior High. Another brother, Clyde Udell Butler, taught shop at Poly High School.

Among the fatalities was shop teacher Lemmie Butler. His brother William Ligon Butler taught shop at William James Junior High School and later was principal of Forest Oak Junior High. Another brother, Clyde Udell Butler, taught shop at Poly High School.

The loss for some families was threefold: three sisters in the Houser family of Overton; three siblings in the Rainwater family of Brachfield, Rusk County; three in the Phillips family of New London; three in the Davidson family of Brazoria, Brazoria County; three in the Williamson family of Vivian, Louisiana.

Identification

Identification of the dead was difficult because many bodies had been blown to pieces. In some cases parts of a body were taken to different morgues for identification.

Many victims were so dismembered that they could be identified only by a birthmark, by clothing, by the contents of their pockets (a whistle, a slingshot, a pocketknife), or by jewelry (a ring, a necklace).

At a temporary morgue in the Overton American Legion hall, a father stood by a sheet-draped figure as a legionnaire showed him his son’s clothing—the only means of identification. The legionnaire brought out a pair of worn half-soled shoes.

“That’s my boy,” the father said softly. “I soled the shoes myself.”

Dallas embalmer Jerome Crane said: “They were the most horribly mangled remains of human beings [I have] ever seen. With the more badly dismembered remains all we could do was to saturate them in embalming fluid and wrap them in cloths for final disposition.”

In the end, rescue workers picked up body parts in tubs and peach baskets.

Some remains were never identified; some missing people were never accounted for.

Horrific as the explosion was, it could have been worse: The school janitor had placed twelve sticks of dynamite, with caps and fuses, under the front steps of the building after working on excavation of the athletic field.

The dynamite was not detonated by the explosion.

Collateral Losses

The fatalities of March 18, 1937 were not confined to the explosion.

A mother, Mrs. Alma Stroud, forty, of Kilgore, spent the night going to temporary morgues looking for the body of her daughter Helen, sixteen. When Mrs. Stroud found Helen’s body she died of a heart attack.

Jesse Couch, thirty, of Wills Point, was killed in a car accident as he rushed to the scene of the disaster.

At Bellville near Houston, Wesley H. Pitkin, an oil field worker, was listening to news of the disaster on the radio when he became mentally unbalanced and began stalking about with a loaded double-barreled shotgun, threatening to kill his wife and four children. Pitkin’s brother Cleaburn called the sheriff’s department. Deputy Sheriff E. F. Reinecker tried in vain to control Wesley Pitkin and shot him to death.

Cleaburn Pitkin said: “Reinecker had to shoot my brother, or my brother would have killed both Reinecker and me.”

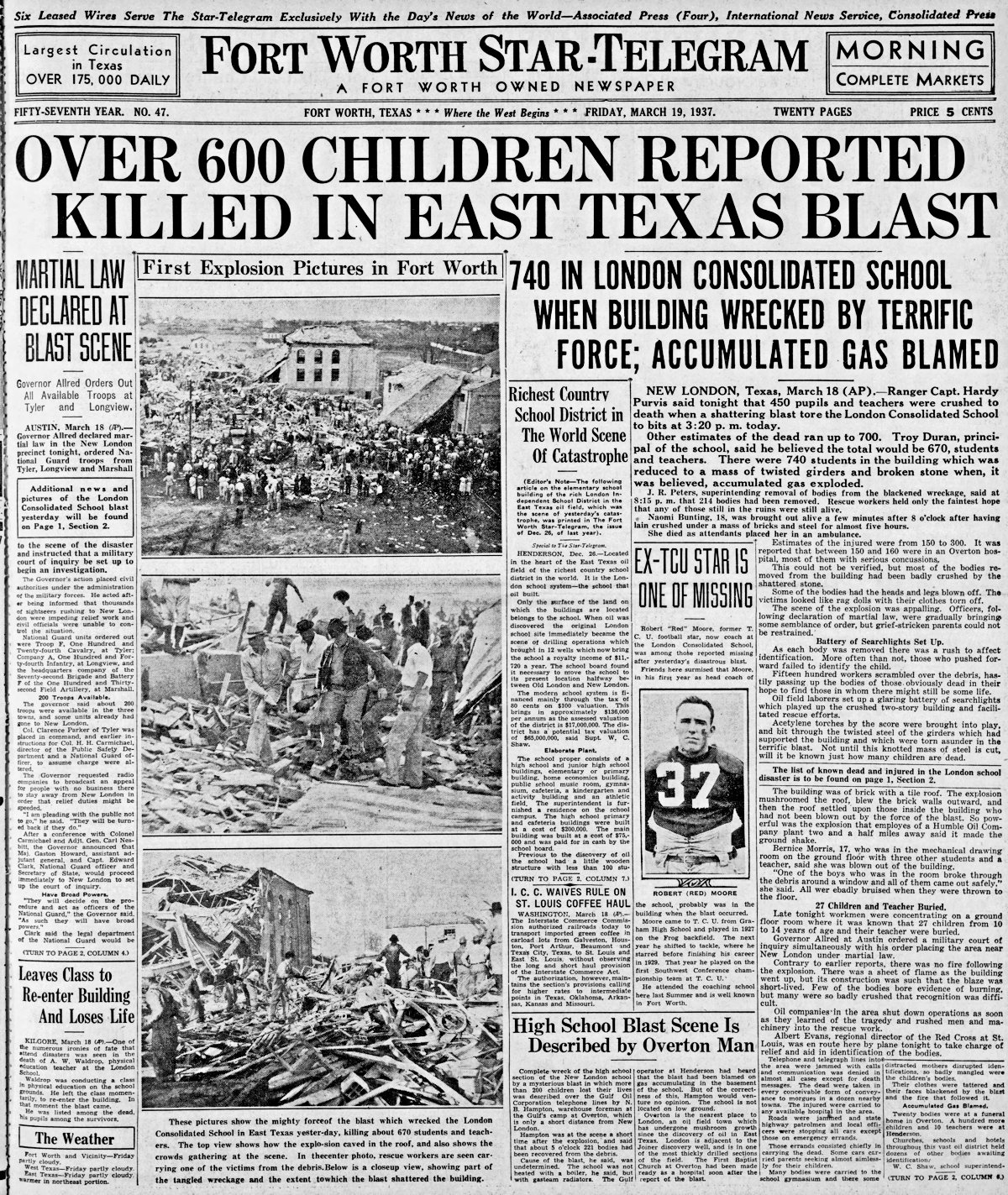

The Kilgore newspaper published an extra edition just hours after the explosion. Predictably, the early estimate of the death toll proved to be inaccurate.

The Kilgore newspaper published an extra edition just hours after the explosion. Predictably, the early estimate of the death toll proved to be inaccurate.

On March 19 the Star-Telegram reported that six hundred were feared dead. Reported to be among the missing was Robert (“Red”) Moore, former TCU football star. Moore was head coach at the New London school. He was later found to be safe.

On March 19 the Star-Telegram reported that six hundred were feared dead. Reported to be among the missing was Robert (“Red”) Moore, former TCU football star. Moore was head coach at the New London school. He was later found to be safe.

Luck

Many had died, but a few had been spared by luck:

Vincent Harold McClure’s older brother Luther, captain of the New London school football team, played hooky to attend the Fort Worth stock show and was spared.

Fifth-grader Bill Thompson traded desks with a classmate so he could flirt with a girl. The boy with whom Thompson traded desks was killed.

Shop teacher Lemmie Butler’s wife also was a teacher at the school. She was absent from school on the day her husband was killed.

A school supply salesman was two minutes late arriving at the school and escaped injury.

Likewise, two minutes before the explosion the school plumber left the building to go to his car for a tool and was spared.

Eighth-grader Nathan Durham had gone to the principal’s office earlier that day to ask to switch his last class to general science. The principal said no. Lucky for Nathan: Every student in that general science class except one was killed. The sole survivor was disabled for life.

Luna Louise Hudson missed school that day because she couldn’t find one of her shoes. Her brother Elisha went to school and died in the explosion.

Seventh-grader Margaret Siler had a headache that day and left the main building to lie down in her uncle’s car. That headache may have saved her life: She was asleep at 3:17 when a chunk of concrete smashed through the front windshield.

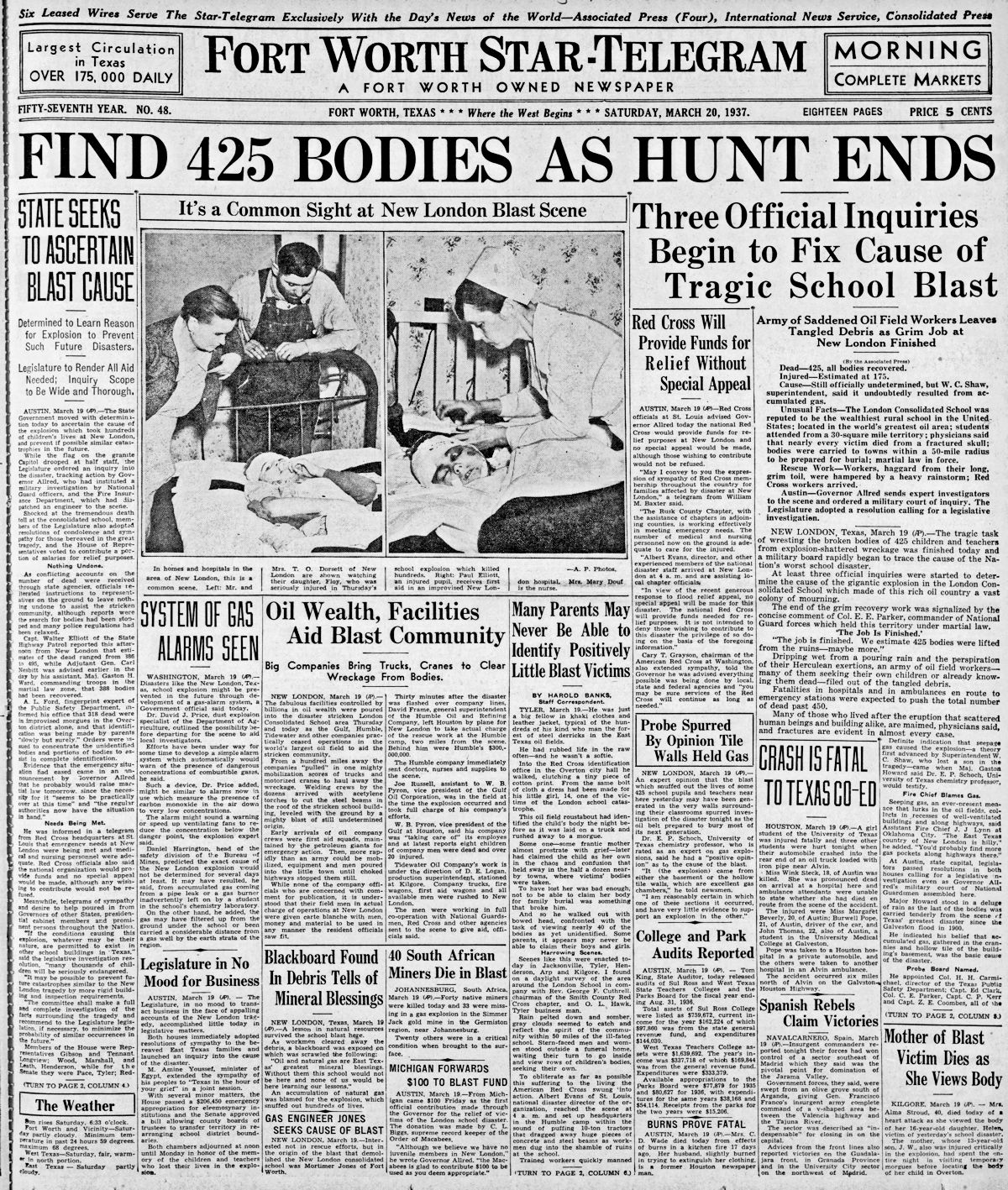

On March 20 the Star-Telegram reported that on March 19 the death toll stood at 425.

On March 20 the Star-Telegram reported that on March 19 the death toll stood at 425.

Also on March 19, after rescuers had worked nonstop for seventeen hours through cold and rain, after workers had removed two thousand tons of rubble and hundreds of victims, National Guard Colonel E. E. Parker, in charge of martial law in New London, declared that the search for the dead and injured was ended.

Burials

And then the funerals began.

The work turned from digging through rubble to digging graves.

Because of the number of fatalities, cremation and mass burial were considered but rejected.

In addition to roughnecks, National Guard troops, airmen, doctors, nurses, and nuns, one other profession was much needed in New London: funeral directors.

Funeral directors came from cities as far away as Fort Worth.

A dozen Fort Worth funeral directors went to New London to help in the grim task, including Morton Ware of Gause-Ware, E. C. Harper of Robertson-Mueller-Harper, Raymond Meissner of Shannon’s, Embry Irwin of Harveson and Cole, and Ray Crowder of Secrest-Crowder.

Fort Worth police traffic officer Theron Brooks, a licensed embalmer, was granted leave to go to New London.

And one other profession was much needed: More than one hundred ministers conducted funerals in a handful of funeral homes and cemeteries in the area.

Each day dozens of funerals were held. A New London druggist listed each day’s scheduled funerals in a front window of his store.

On March 20 three freight cars bearing coffins arrived, with more on the way.

In Overton highway patrolmen halted traffic on a state highway through town so that coffins could be moved from temporary storage in an automobile showroom to a funeral home across the highway.

In cemeteries traffic was gridlocked as hearses and vehicles bearing mourners backed up for a mile in some cases.

Police stood at crossroads and directed funeral traffic.

National Guard troops filled in as pallbearers.

At night burials were held by the light of automobile headlights. Mourners stood by graves past midnight.

Most victims were buried locally, the majority (seventy-plus) in New London’s Pleasant Hill Cemetery, but some victims were buried in small-town and church cemeteries elsewhere in Rusk County: Overton, Henderson, Minden, Pitner Junction, Crims Chapel.

And other victims, including Vincent Harold McClure and Rosean Sailsberry, were buried elsewhere—in counties across Texas: Tarrant, McLennan, Young, Cherokee, Blanco, Hood, Wise, Wilbarger.

In Dallas two police officers watched an old truck rattle slowly along a street. A rough pine box protruded from the rear of the truck. In front of the license plate was a handwritten sign: “Funereal.”

The word was misspelled, but officers Larry Knight and Ed Preston suspected what it meant. They stopped the truck.

“Where to?” the officers asked the two glazed-eyed occupants.

“West Texas.”

“Was it . . . the explosion?”

“Yes. I’m taking her home.”

Knight later said, “I was in France in the Argonne. But this, well, this is different.”

Bodies also were returned to other states: Louisiana, Oklahoma, Mississippi, Arkansas, Alabama.

As the week ended, tombstones joined oil derricks as the new skyline of Rusk County.

Death Toll

The death count has been put at 311, at least 270 of them children. But 311 is only an estimate because some bodies were never identified.

Authorities also suspect that the death toll was higher because some roughnecks moved away, taking the body of their dead child away for burial elsewhere before the death could be recorded.

Likewise, some of the fatalities were the children of Mexican immigrants who had come north to work in the Rusk County oil fields. Some of these families loaded up their dead child and returned home to mourn.

Of the six hundred people in the building when it exploded, only about 130 escaped without being killed or seriously injured.

To honor the New London victims, Governor Allred declared March 21 a day of mourning and ordered state flags to be lowered to half-staff.

Reaction

The New London school disaster was news from coast to coast.

The New London school disaster was news from coast to coast.

And in England and Australia.

And in England and Australia.

German Chancellor Adolph Hitler sent a message to President Roosevelt: “On the occasion of the terrible explosion at the New London, Tex., which took so many young lives, I want to assure your excellency of my and the German people’s sincere sympathy.”

U.S. House of Representatives chaplain James Shera Montgomery opened the House’s session with a prayer that included these words: “Thou who canst fill with comfort broken hearts, broken loves, and broken lives, be Thou the angel of consolation in that sorely stricken district in our southland. In their deepest sorrow and saddest bereavement, unveil Thy face in every home, where tragedy is so deep and overwhelming.”

Life Goes On

Ten days after the disaster, classes at New London school resumed in the school’s surviving buildings. Snow fell as school buses arrived carrying a fraction of their normal number of passengers.

To keep warm in the buildings, students burned wood—not gas—in stoves. The wood was the splintered lumber of the demolished school building.

The Cause

An investigation concluded that the explosion occurred because the school building’s connection to the residue gas pipe had leaked, allowing the building’s basement and possibly the hollow tile blocks of the building’s walls to fill with natural gas. When shop teacher Butler switched on an electric sander at 3:17 p.m., a spark from the switch ignited the accumulated gas.

Natural gas was colorless and, at that time, odorless. Students had been complaining of headaches for sometime, but school officials had paid little attention to those complaints.

After the explosion a lawsuit was brought against the school district and the Parade Gasoline Company, but a court ruled that neither was at fault.

Although no one was found to be at fault, Superintendent W. C. Shaw was forced to resign amid talk of lynching. He had lost a son, niece, and nephew in the explosion.

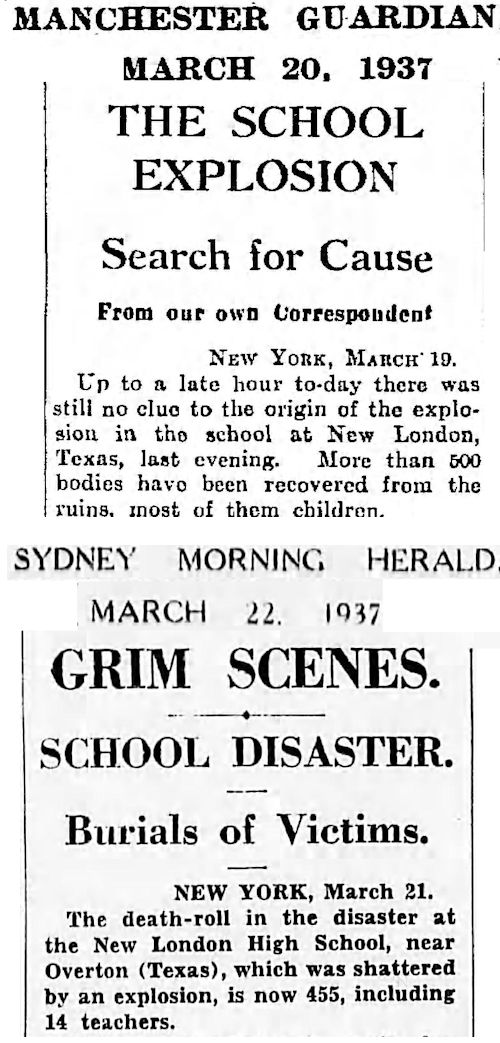

In 1939 the school building was rebuilt behind the site of the demolished building.

In 1939 the school building was rebuilt behind the site of the demolished building.

Legacy

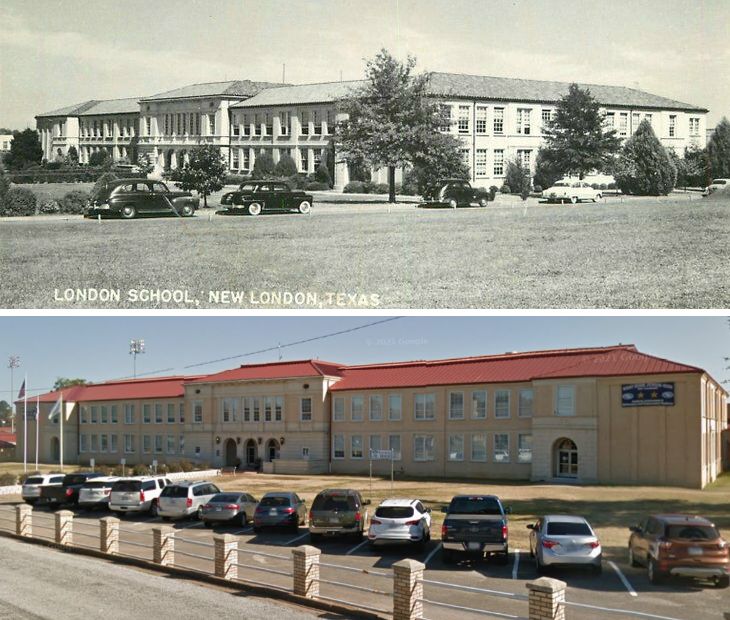

The Texas legislature, in reaction to the New London tragedy, mandated that mercaptan, a harmless chemical, be added to natural gas to give it a detectable odor. The addition of mercaptan is now a standard practice in the industry nationwide.

Lone Star Gas Company began adding mercaptan in June.

Lone Star Gas Company began adding mercaptan in June.

The New London school explosion is the third-deadliest disaster in Texas history, after the 1900 Galveston hurricane (about 8,000 killed) and the 1947 Texas City disaster (at least 581 people killed).

British Pathe newsreel

British Pathe newsreel

Universal newsreel

And the Legislature established the Texas Board of Architectural Examiners.

The book, “Gone at 3:17” is a definite read about this horrible incident. I have for years intended to drive to New London and pay my respects in the cemetery, maybe I will this weekend. Thank you for reminding us all of this tragedy and the amazing people who worked so hard in the aftermath.