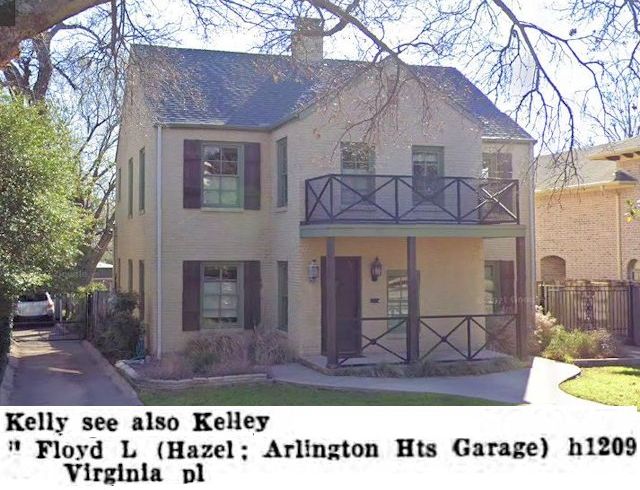

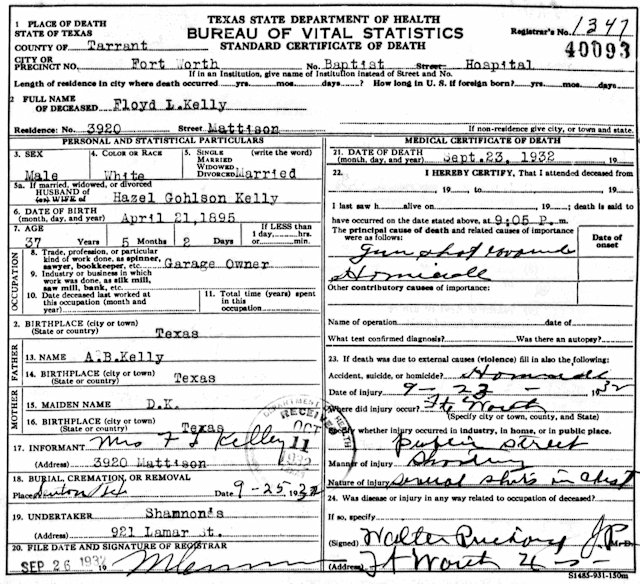

Floyd Lynn Kelly was born in 1895 in the Parker County community of Lakota (later called “Bennett,” home of George Bennett’s Acme brick plant). In 1932 Kelly and wife Hazel lived on Virginia Place in Hi Mount in Arlington Heights. Kelly owned a gas station on West 7th Street.

Floyd Lynn Kelly was born in 1895 in the Parker County community of Lakota (later called “Bennett,” home of George Bennett’s Acme brick plant). In 1932 Kelly and wife Hazel lived on Virginia Place in Hi Mount in Arlington Heights. Kelly owned a gas station on West 7th Street.

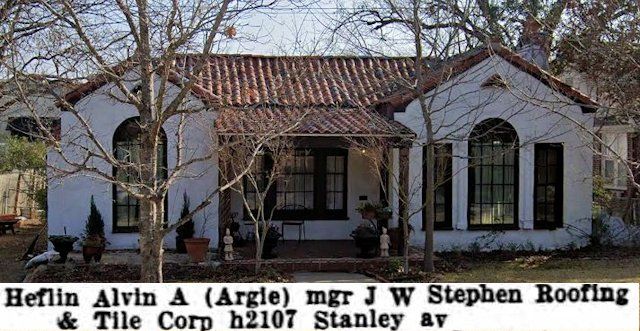

Alvin Arthur Heflin was born in 1892 in Valley Mills. In 1932 he and wife Argie lived on Stanley Avenue in Berkley. Alvin Heflin managed a roofing and tile company.

Alvin Arthur Heflin was born in 1892 in Valley Mills. In 1932 he and wife Argie lived on Stanley Avenue in Berkley. Alvin Heflin managed a roofing and tile company.

Our story so far: a gas station owner and a roofing company manager—two prosaic enough occupations, right?

But Floyd Kelly had a night job: bootlegger.

Alvin Heflin also had a night job: federal Prohibition informant.

Although their night jobs put Kelly and Heflin at odds, the two men did have something in common:

Heflin’s wife.

On the night of September 23, 1932 moonshine met matrimony in the lobby of the Hollywood Theater.

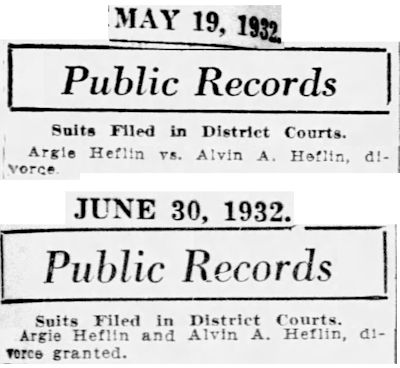

If the story of the Kellys and the Heflins were a movie script, the summer of 1932 created the motivations of the plot’s two antagonists. In May Mrs. Heflin filed for divorce from her husband. In June Mrs. Heflin was granted a divorce. Mr. Heflin was awarded all of the marriage’s property and custody of its two daughters.

If the story of the Kellys and the Heflins were a movie script, the summer of 1932 created the motivations of the plot’s two antagonists. In May Mrs. Heflin filed for divorce from her husband. In June Mrs. Heflin was granted a divorce. Mr. Heflin was awarded all of the marriage’s property and custody of its two daughters.

Mr. Heflin did not contest the divorce, but he did blame Floyd Kelly for breaking up his marriage: Kelly had been stepping out with Heflin’s wife.

So, there is antagonist Alvin Helfin’s motivation for hating Floyd Kelly.

Then Heflin found out—perhaps by spying on his wife and Kelly—that Kelly was pumping more than ethyl at his gas station at 3013 West 7th Street: Kelly was the leader of a bootlegging ring who made and sold illegal beer and liquor in a one hundred-mile radius of Fort Worth. Prohibition had been in effect twelve years in 1932.

The ring had fifteen members, including Kelly, his mechanic Roy Swann, and one woman, Cleo Johnson, whose White Face Café on Exchange Avenue was an outlet for the moonshine.

Informant Heflin passed this information along to federal Prohibition agents, who wiretapped the telephone of Kelly’s gas station from an apartment in the 2800 block of West 7th Street (probably the Ashwood Apartments at 2808). (Burleson Street today is University Drive.)

Informant Heflin passed this information along to federal Prohibition agents, who wiretapped the telephone of Kelly’s gas station from an apartment in the 2800 block of West 7th Street (probably the Ashwood Apartments at 2808). (Burleson Street today is University Drive.)

Agents monitored 350 telephone conversations to and from the station between August 10 and August 21.

A sample of what the agents heard:

August 13

“Hello,” said a woman telephoning from the station. “White Face Cafe? 6-2034? Is Hawk there? [“Hawk” was a nickname of ring member Jim Swenson.] Well, tell him to send sixteen cases of beer over to the old man’s place. He’s raising h— because the beer’s flat.”

“The beer here’s flat, too.”

“Well, snap out of it, or I’ll fire you and him, too.”

August 18

A man, telephoning the gas station, said: “This is [ring member Boyd] Shannon. The sheriff’s office called and said something was in the air. Said anything might happen tonight, that it might happen this evening.”

August 19

“Hello,” answered a man at the station.

A woman caller: “Is [ring member] Shipley there? This is Cleo—did you call me?”

“Yes, deputy marshal Wheeler Smith called.”

“What did he want?”

“I don’t know. He said to come to see him.”

“All right.”

“If there’s any trouble, call me.”

Also on August 19 a person at the station telephoned 2-4291.

“Hello,” answered a woman.

“Is Mr. Smith there?” the caller asked.

“Just a minute.”

The woman’s voice was replaced by a man’s.

“This is Shipley,” the caller said. “Did you talk to Cleo?”

“Yes. I called to tell her the woods were full of ’em [federal Prohibition agents]. There are a lot of search warrants out. You’d better look out.”

“Yes, I know it’s hot.”

“They’ve got a lot of new ones [agents] in town. My name’s ‘Ferguson,’ you know.”

“Thanks, Mr. Ferguson. I’ll call Cleo.”

A few minutes later a telephone call was placed from the station to 6-0185.

“Hello,” answered a woman.

“Cleo?”

“Yes.”

“I just talked to that party.”

“What did he say?”

“He tried to call you to tell you if you had anything you’d better get rid of it. The woods are full of ’em. Lot of search warrants out.”

Also on August 19 a city motorcycle officer telephoned the station and reproached the answerer for failing to deliver a case of beer to his address on 4th Street.

The answerer said, “I had it 5th Street—I’ll bring it this afternoon.”

Also on August 19 Shipley answered a telephone call to the station:

Shipley: “Hello.”

“Say, Shipley, isn’t that place [to deliver liquor] back of that Federal Building? Do you know it’s all right?”

Shipley: “Sure. It’s a law[man]. He’s okay.”

So. Here are three takeaways from these conversations for federal Prohibition agents:

- They confirmed that Kelly’s ring was selling illegal liquor.

- They learned that a U.S. deputy marshal (Smith aka Ferguson) apparently was tipping off the ring about impending raids by law enforcement.

- They learned that among the ring’s customers apparently were members of law enforcement.

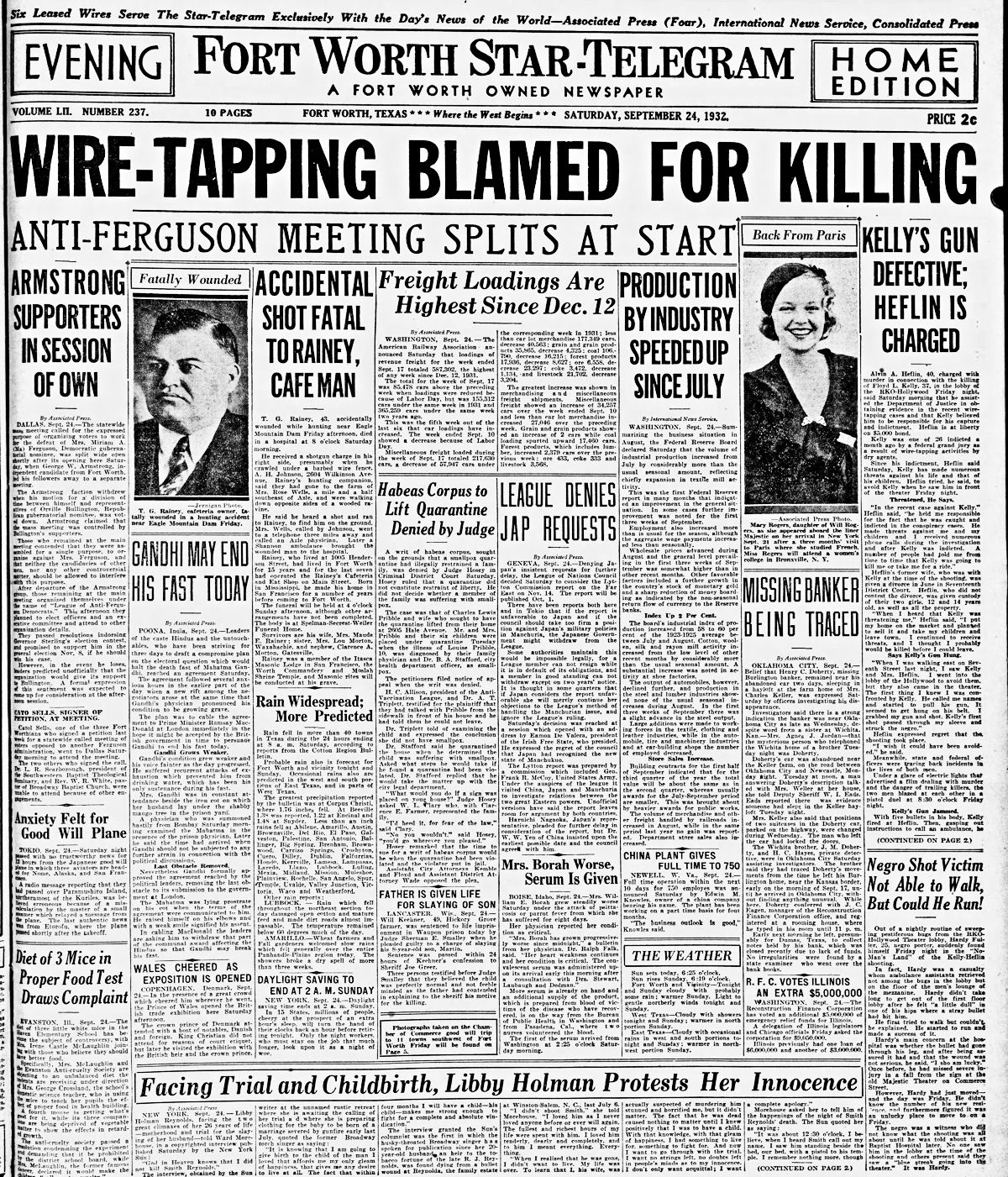

The Star-Telegram reported that the wire-tap operation was jeopardized when a landlady found a wire-tap device in an apartment, and her discovery was publicized. As a result, some bootleggers went underground. Other bootleggers began to shadow the federal agents, who said they were watched “from the time we left our hotel rooms every morning until we returned at night.”

The watchers had become the watched.

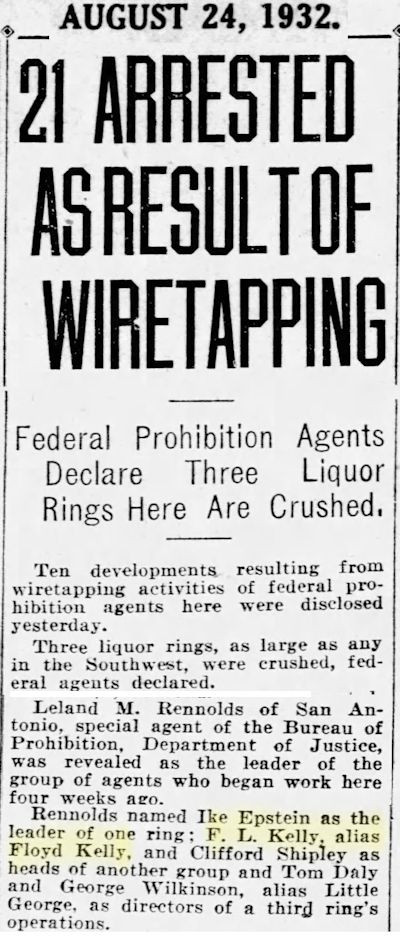

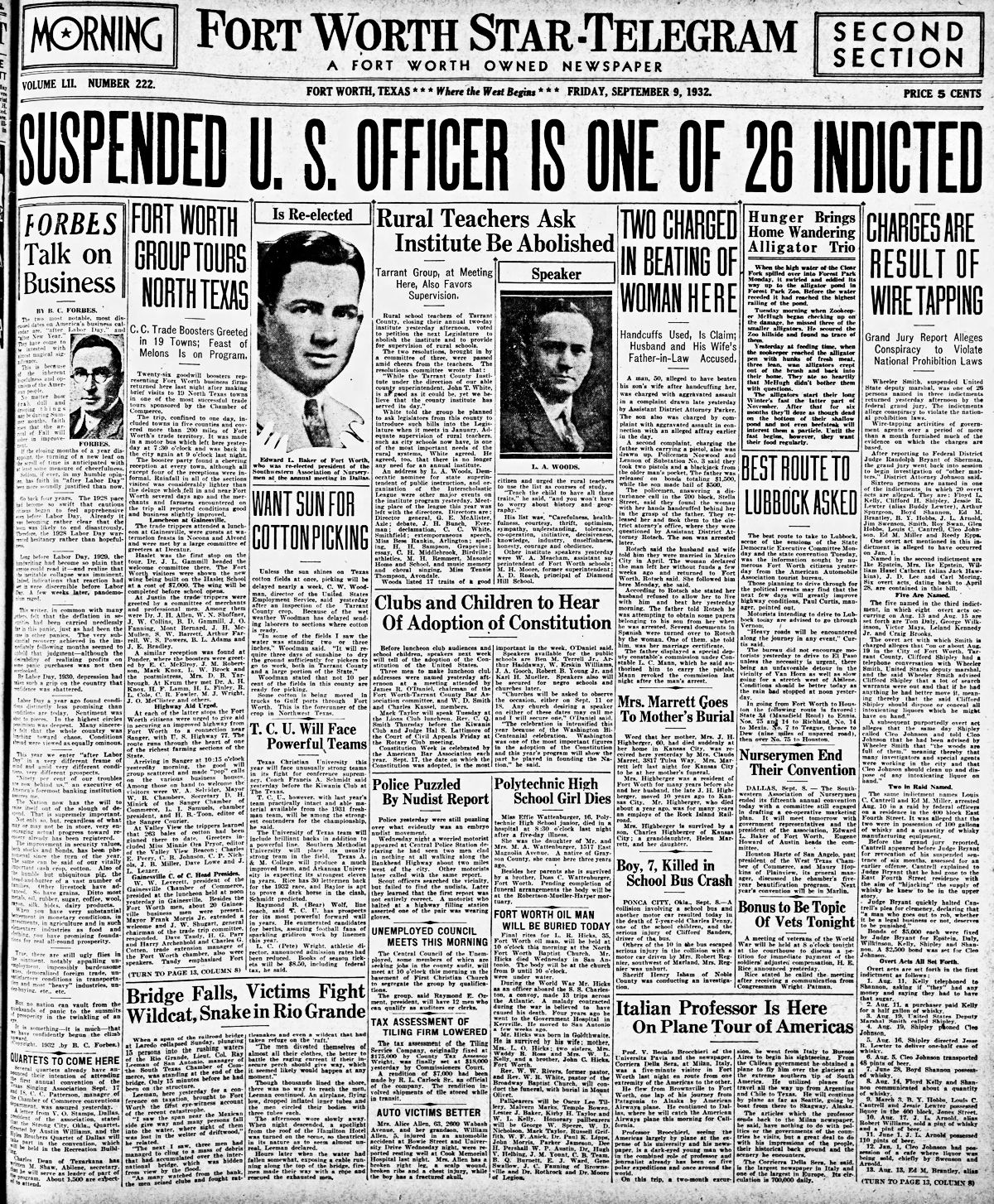

Nonetheless, on August 24 the Star-Telegram announced that federal “dry” agents had arrested twenty-one people as “three liquor rings, as large as any in the Southwest, were crushed.”

Nonetheless, on August 24 the Star-Telegram announced that federal “dry” agents had arrested twenty-one people as “three liquor rings, as large as any in the Southwest, were crushed.”

Among those arrested was Floyd Kelly. Also arrested was U.S. deputy marshal Harris Wheeler Smith, charged with tipping off bootleggers about impending raids.

Among those arrested was Floyd Kelly. Also arrested was U.S. deputy marshal Harris Wheeler Smith, charged with tipping off bootleggers about impending raids.

Kelly and Smith and twenty-four others were indicted on September 8 for violations of federal Prohibition laws.

Kelly and Smith and twenty-four others were indicted on September 8 for violations of federal Prohibition laws.

Kelly was freed on $5,000 ($100,000 today) bond.

Floyd Kelly blamed informant Alvin Heflin for his arrest.

So, there is antagonist Floyd Kelly’s motivation for hating Alvin Heflin.

Now our movie plot has an isometric tension: Each antagonist has a motivation for hating the other.

After Kelly was indicted and freed on bond, Heflin began to receive reports that Kelly was making threats against the life of Heflin and his two children.

Heflin later recalled: “When I heard that Kelly was threatening me, I put my home on the market and planned to sell it and take my children and leave town. I continued to receive threats, and I thought I probably would be killed before I could leave.”

Assistant District Attorney William Parker asked Kelly about a rumor that Kelly was having Heflin “shadowed.”

Kelly denied the rumor.

Heflin carried a gun: He had a permit. Kelly also carried a gun—as much a part of a bootlegger’s equipment as copper tubing and Mason jars.

So, now our movie script has two armed men, each with a grudge against the other.

All that our script lacks now is a climax.

And that is our cue to segue to the 400 block of West 7th Street.

[Sidewalk in front of Hollywood Theater. September 23, 1932.]

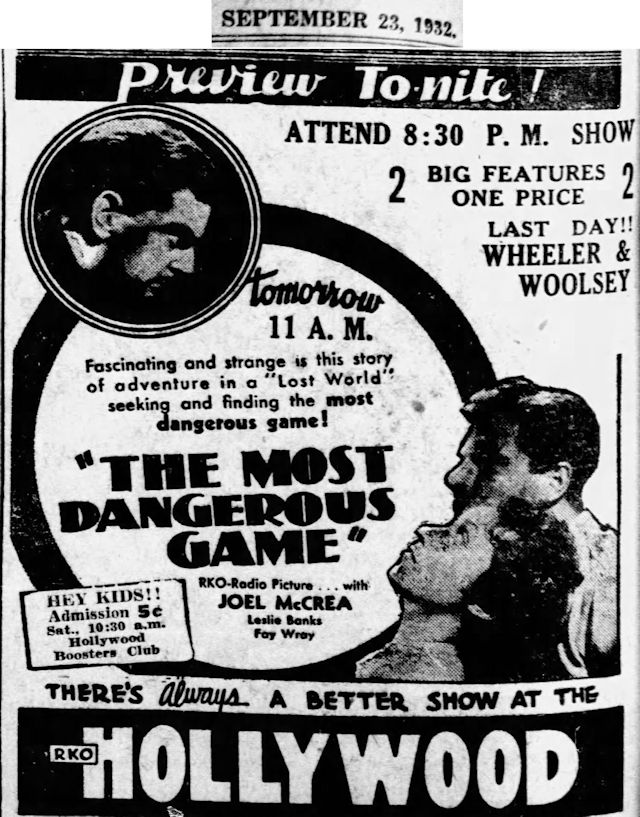

The time was 8:30 p.m. A sneak preview of the movie The Most Dangerous Game (about a man who hunts men for sport) was about to begin. Theatergoers were lining up on the sidewalk in front of the theater.

On September 24 Alvin Heflin recalled the scene that night:

On September 24 Alvin Heflin recalled the scene that night:

“When I was walking east on 7th Street last night, I saw Kelly and Mrs. Heflin. I went into the lobby of the Hollywood to avoid them, but they also came in the theater.”

Had Kelly gone into the lobby merely to see the movie, or had he seen Heflin on the sidewalk and had followed him into the lobby to corner and kill him?

Heflin recalled: “The first thing I knew I was confronted by Kelly. He called me names and started to pull his gun.”

Suddenly the most dangerous game played out in the lobby, not on the screen.

Heflin recalled: “It [Kelly’s pistol] seemed to get hung on his belt. I grabbed my gun and shot. Kelly’s first shot passed through my sleeve and struck the Negro [Hollywood Theater porter Hardy Fuller, who was slightly injured].”

After Kelly fired one shot, his gun jammed.

Heflin’s did not.

As bullets flew, people on the sidewalk and in the theater lobby screamed. Some in the theater ran to the exits; others dropped to the floor.

Someone shouted that a bomb had been thrown.

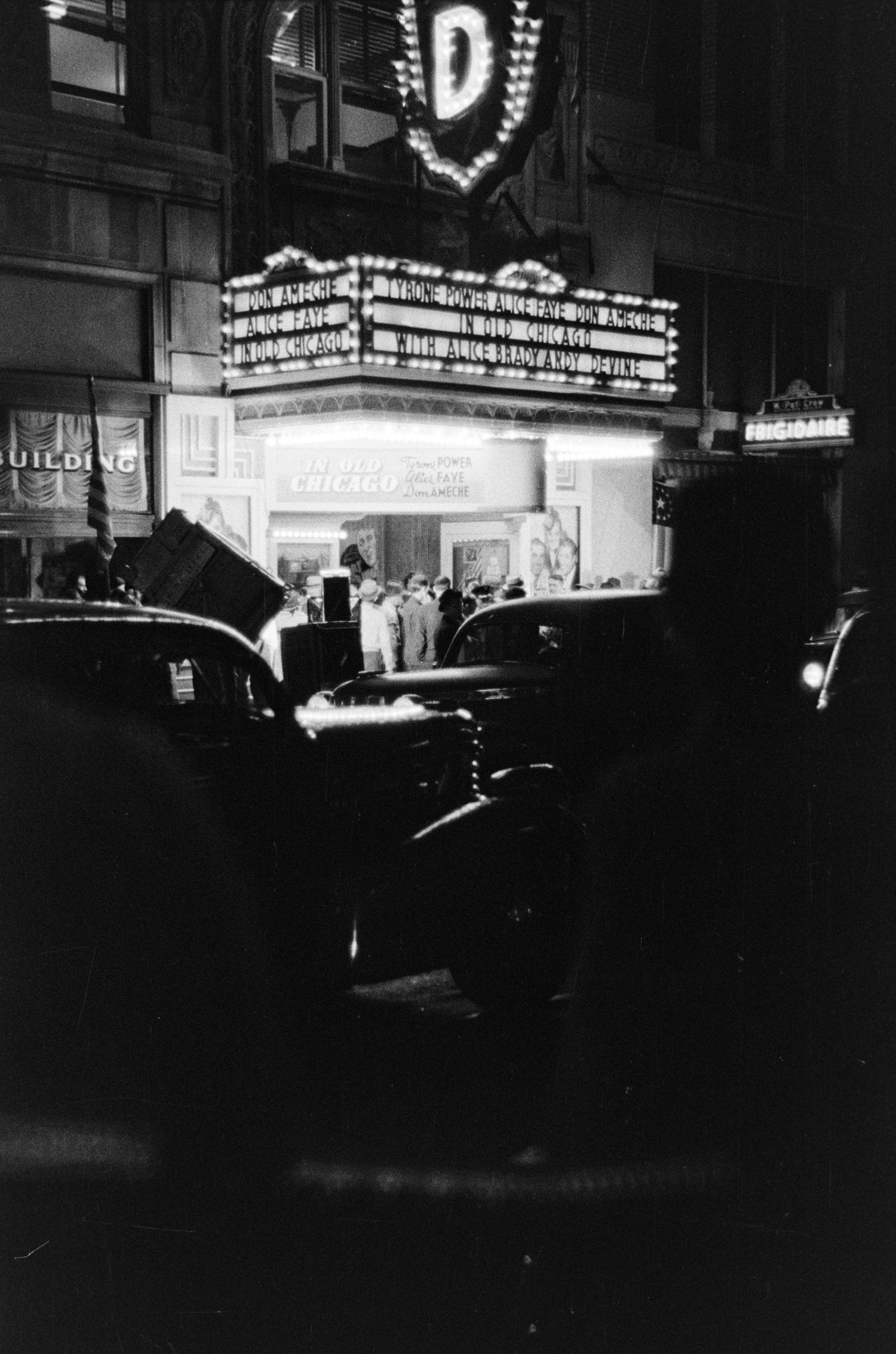

Across the street at the Neil P. Anderson Building, night watchman George McCarroll thought the shootout in the theater was between a police officer and a robber.

McCarroll later said: “Heflin was on the west side of the box office, and Kelly on the east side when I saw them. They seemed to be ducking each other’s bullets by dodging around the box office.”

The entrance of the Hollywood Theater in 1938. (Photo from Byrd Williams Family Photography Collection, University of North Texas Special Collections.)

The entrance of the Hollywood Theater in 1938. (Photo from Byrd Williams Family Photography Collection, University of North Texas Special Collections.)

The Star-Telegram wrote on September 24:

“Heflin fired twice as Kelly sprang behind the ticket booth of the theater. Heflin ran a few steps from the entrance but turned as Kelly followed. Heflin shot three more times. Kelly shot once as the other man [Heflin] ran into the lobby of the Electric Building.

“Harry W. Schlinker, theater manager, narrowly escaped being struck by one of the bullets as he stood at the rear of the lobby. The missile chipped the marble wall behind him.

“Coughing hoarsely, Kelly stepped to the ticket window and asked Mrs. Edith Williams, cashier, to call an ambulance. He slumped to the floor of the lobby with blood streaming from wounds in his chest.”

Mrs. Heflin bent over Kelly and begged him to speak to her.

After the shootout Heflin ran toward his car parked in the 700 block of Lamar Street, but he was stopped by night watchman McCarroll, who threatened to shoot.

In the theater lobby police officer Walter Schertz, who had been attending the movie, took Kelly’s pistol from his limp hand. Schertz then followed McCarroll in the pursuit of Heflin, took Heflin’s revolver from him, and placed him under arrest.

Mrs. Heflin accompanied Kelly to Baptist Hospital, where he died soon after admittance. He had been shot five times.

Mrs. Heflin accompanied Kelly to Baptist Hospital, where he died soon after admittance. He had been shot five times.

After the shooting stopped, theater ushers tried to calm patrons by telling them that some kids had ignited firecrackers.

After the shooting stopped, theater ushers tried to calm patrons by telling them that some kids had ignited firecrackers.

Heflin told police: “He [Kelly] said he would get me. But I got him, all right. I emptied my gun at him not ten feet away. I was shooting at his heart.”

Alvin Heflin was charged with murder and released on $5,000 bond.

Heflin told police: “In the recent case [of bootlegging] against Kelly, he held me responsible for the fact that he was caught and indicted . . . He made threats against me and my children, and I received numerous phone calls during the investigation and after Kelly was indicted. A number of people had told me from time to time that Kelly was going to kill me or take me for a ride.”

Heflin told police: “In the recent case [of bootlegging] against Kelly, he held me responsible for the fact that he was caught and indicted . . . He made threats against me and my children, and I received numerous phone calls during the investigation and after Kelly was indicted. A number of people had told me from time to time that Kelly was going to kill me or take me for a ride.”

Floyd Lynn Kelly is buried in Denton County.

Floyd Lynn Kelly is buried in Denton County.

Plot resolution 1: On September 27 the district attorney’s office announced that a grand jury would be empaneled to investigate the fatal shooting of Floyd Kelly. Meanwhile, Mrs. Kelly couldn’t get her husband back—from Mrs. Heflin or from the Grim Reaper. But maybe she could get her stuff back: Four days after Alvin Heflin killed Floyd Kelly, Kelly’s widow sued Mrs. Heflin to reclaim property—jewelry and a refrigerator—that Floyd Kelly had given to Mrs. Heflin.

Plot resolution 1: On September 27 the district attorney’s office announced that a grand jury would be empaneled to investigate the fatal shooting of Floyd Kelly. Meanwhile, Mrs. Kelly couldn’t get her husband back—from Mrs. Heflin or from the Grim Reaper. But maybe she could get her stuff back: Four days after Alvin Heflin killed Floyd Kelly, Kelly’s widow sued Mrs. Heflin to reclaim property—jewelry and a refrigerator—that Floyd Kelly had given to Mrs. Heflin.

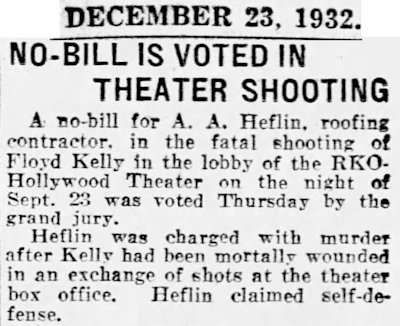

Plot resolution 2: Alvin Arthur Heflin was no-billed by the grand jury.

Plot resolution 2: Alvin Arthur Heflin was no-billed by the grand jury.

[Fade to black.]

The End

Cowtown Goes Hollywood: “Fort Worth’s Newest Movie Cathedral”

Triple Feature: When 7th Street Was Show Row

Posts About Cinema in Cowtown

This shootout At the movies was great.

Thanks, Kathy. Can’t make up stuff like this.