Late on a hot summer night in 1961 four men raced down East Lancaster Avenue toward a metaphorical crossroads.

One crossroads, four men, four possible directions.

One crossroads, four men, four possible directions.

Arriving at that crossroads, one man went in a direction that led to a long and uninterrupted life.

Two men went in directions that led to prison.

The fourth man went in a direction that led to his grave.

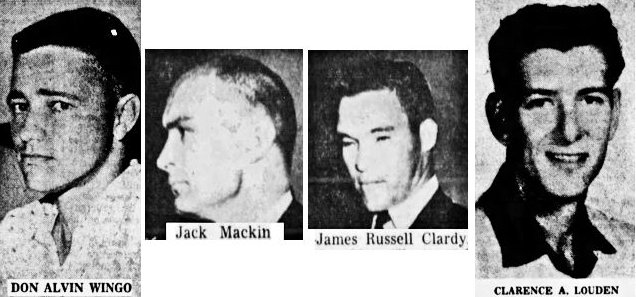

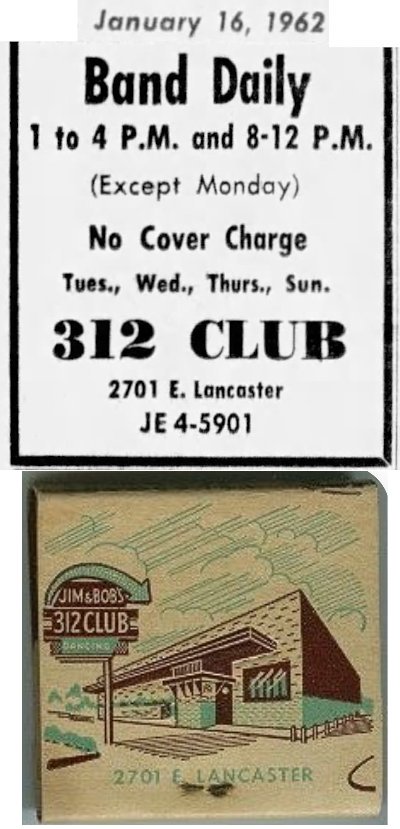

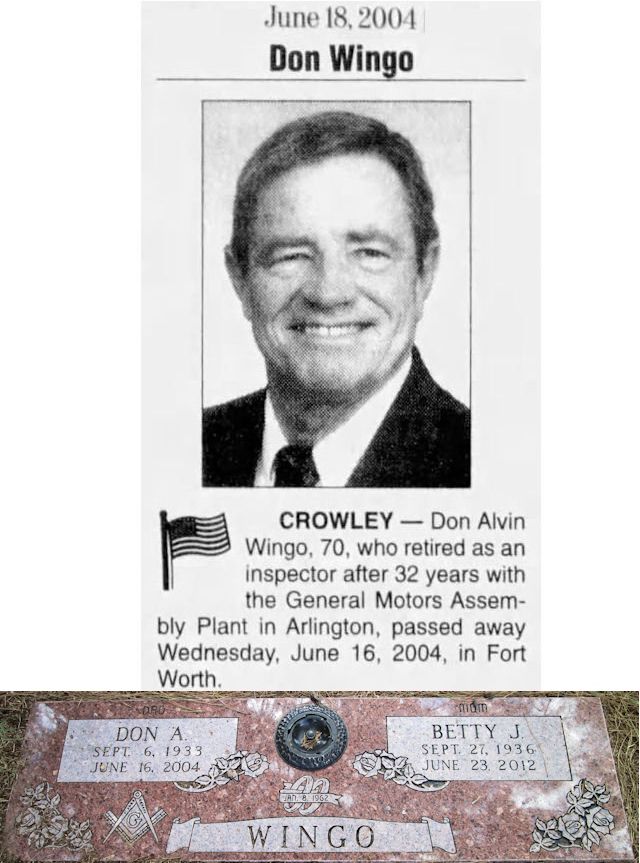

1. Don Alvin Wingo was born in Fort Worth, attended Paschal High School. He served on the Navy carrier USS Oriskany in the Korean War. In 1955 he married. His bride Janice was young: sixteen at most. By the time she divorced him in November 1960 they had two children. By August 1961 Wingo was $1,000 behind in his child support payments. A warrant for his arrest had been issued.

1. Don Alvin Wingo was born in Fort Worth, attended Paschal High School. He served on the Navy carrier USS Oriskany in the Korean War. In 1955 he married. His bride Janice was young: sixteen at most. By the time she divorced him in November 1960 they had two children. By August 1961 Wingo was $1,000 behind in his child support payments. A warrant for his arrest had been issued.

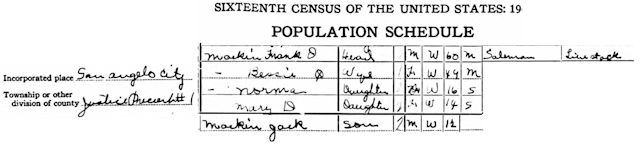

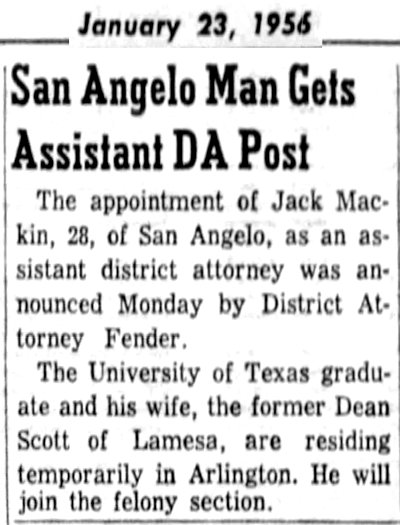

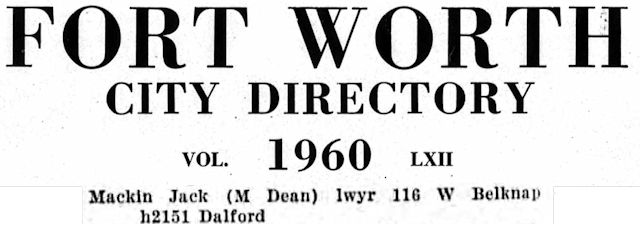

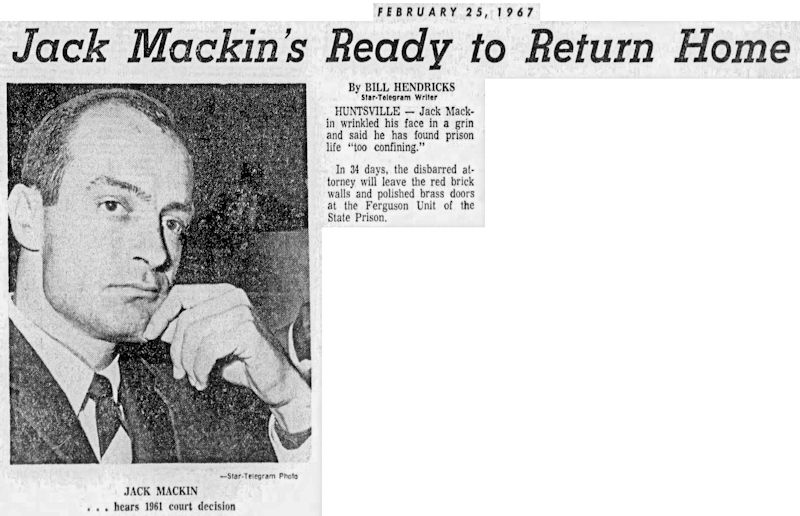

2. Jack Mackin was born in San Angelo. His father died young, and Jack dropped out of school to work. After one year of high school and three years in the Army Air Forces, Mackin talked his way into San Angelo Junior College and then transferred to the University of Texas, where he pushed himself, taking as many as twenty-four semester hours at a time. In 1949 he married Melva Dean Scott.

2. Jack Mackin was born in San Angelo. His father died young, and Jack dropped out of school to work. After one year of high school and three years in the Army Air Forces, Mackin talked his way into San Angelo Junior College and then transferred to the University of Texas, where he pushed himself, taking as many as twenty-four semester hours at a time. In 1949 he married Melva Dean Scott.

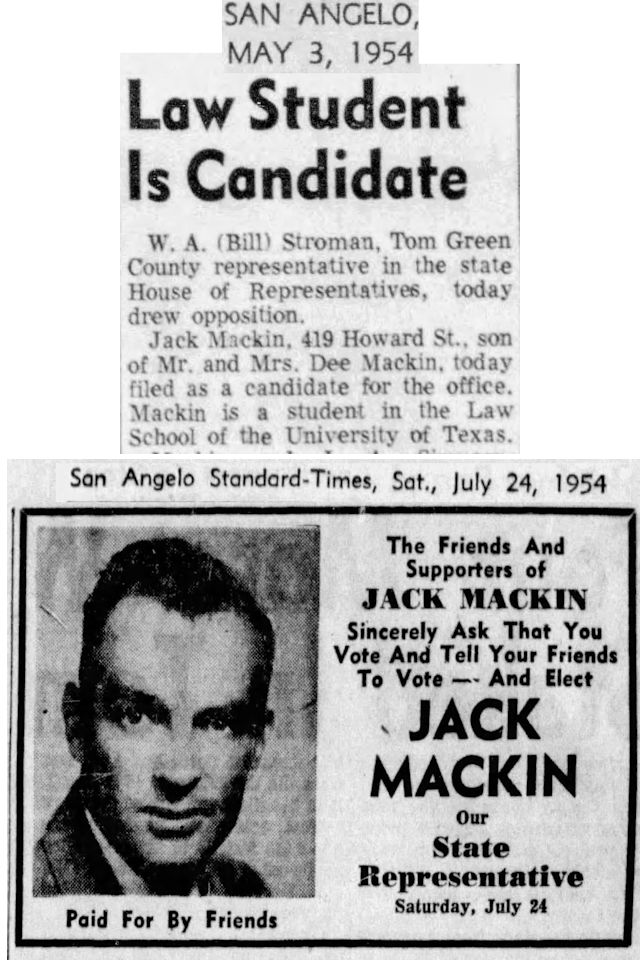

Mackin went on to law school and while a student ran—unsuccessfully—for the state legislature.

Mackin went on to law school and while a student ran—unsuccessfully—for the state legislature.

Just out of law school at age twenty-eight Mackin was hired as a Tarrant County assistant district attorney.

Just out of law school at age twenty-eight Mackin was hired as a Tarrant County assistant district attorney.

But after six months Mackin resigned to practice as a criminal defense attorney.

But after six months Mackin resigned to practice as a criminal defense attorney.

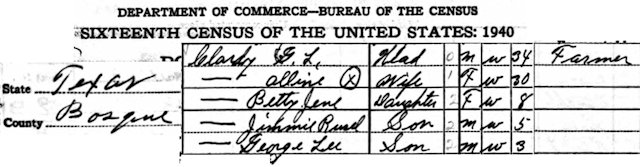

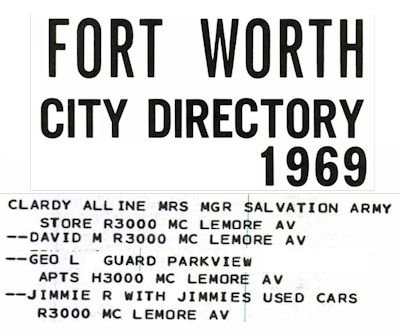

3. James Russell (“Jimmy”) Clardy was born on his father’s farm in Bosque County.

3. James Russell (“Jimmy”) Clardy was born on his father’s farm in Bosque County.

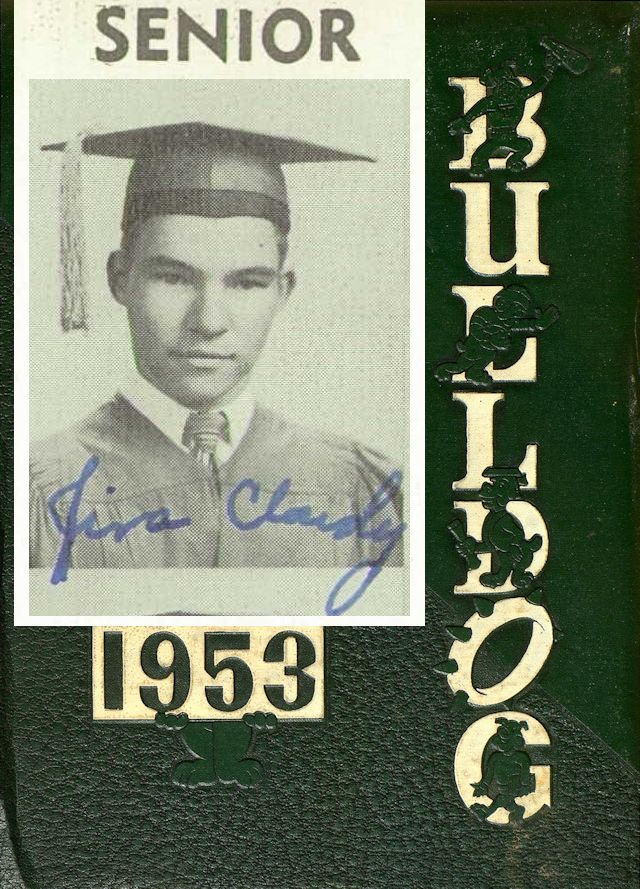

Clardy graduated from Fort Worth’s Technical High School in 1953.

Clardy graduated from Fort Worth’s Technical High School in 1953.

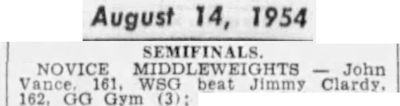

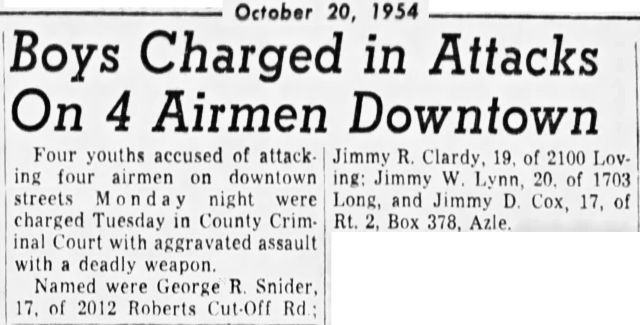

He boxed in the Golden Gloves program in the 1950s, got into a few scrapes with the law but also worked as a police officer in Mansfield, Kennedale, and Sansom Park. In 1955 he married. He and wife Nanola had two children.

He boxed in the Golden Gloves program in the 1950s, got into a few scrapes with the law but also worked as a police officer in Mansfield, Kennedale, and Sansom Park. In 1955 he married. He and wife Nanola had two children.

By 1961 Clardy operated a used car lot at 2505 East Belknap Street.

By 1961 Clardy operated a used car lot at 2505 East Belknap Street.

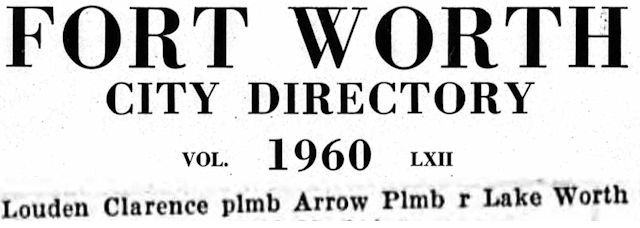

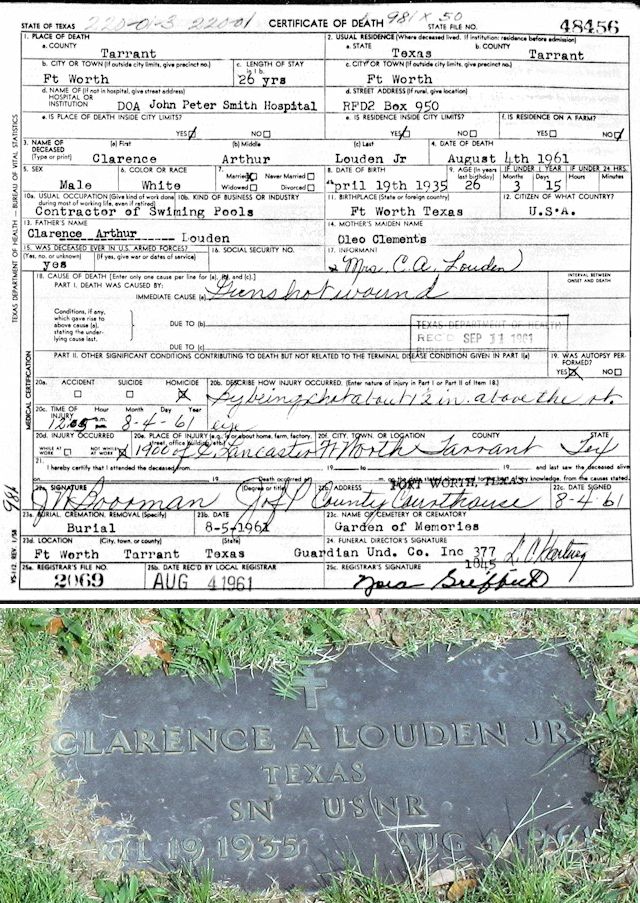

4. Clarence Arthur (“Buddy”) Louden Jr. served on the USS Hancock in the Navy in the 1950s. By 1960 he was married with two children. He worked for a plumbing company and lived at Lake Worth. By 1961 he had gone out on his own: He was a swimming pool contractor. One of his employees was Don Alvin Wingo.

4. Clarence Arthur (“Buddy”) Louden Jr. served on the USS Hancock in the Navy in the 1950s. By 1960 he was married with two children. He worked for a plumbing company and lived at Lake Worth. By 1961 he had gone out on his own: He was a swimming pool contractor. One of his employees was Don Alvin Wingo.

These are the four men who met at a crossroads on the night of August 3, 1961.

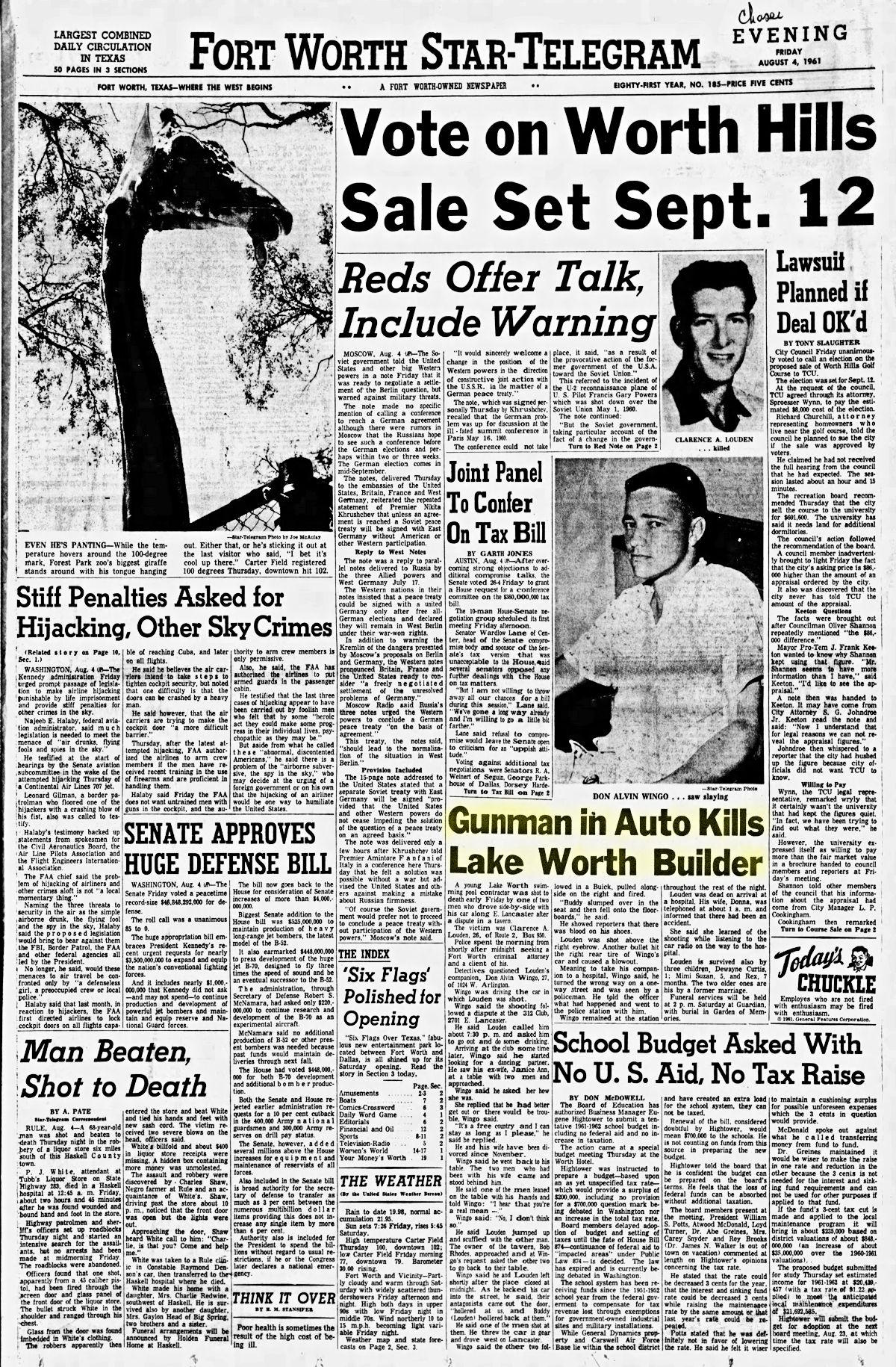

The facts: In a nightclub at 2701 East Lancaster Avenue, Don Wingo and Buddy Louden exchanged heated words with Jimmy Clardy and Jack Mackin. Just after midnight Wingo and Louden left the nightclub together and traveled west on East Lancaster. Clardy and Mackin, pursuing in another car, pulled alongside the Wingo-Louden car.

The four men speeding down East Lancaster Avenue that night were not hot-headed teenagers. Louden was twenty-six. His companion, Wingo, was twenty-seven. Clardy and Mackin were twenty-six and thirty-three.

The four men speeding down East Lancaster Avenue that night were not hot-headed teenagers. Louden was twenty-six. His companion, Wingo, was twenty-seven. Clardy and Mackin were twenty-six and thirty-three.

When Jimmy Clardy pulled alongside Don Wingo’s car in the 1900 block of East Lancaster at the intersection of East Lancaster and Windham Street, that intersection became a crossroads for the four men.

Irrevocable decisions were made.

Two gunshots were fired.

Buddy Louden slumped and fell to the floorboard.

Louden had been shot once above the right eyebrow. Another bullet punctured a tire of Wingo’s car.

Minutes later a police officer stopped Wingo, who was driving the wrong way on a one-way street with a flat tire on a rear wheel and a dead body on the floorboard.

Buddy Louden did not live to give his account of the events of that night, so here are the accounts of the other three men who stood at the crossroads.

Buddy Louden did not live to give his account of the events of that night, so here are the accounts of the other three men who stood at the crossroads.

Don Wingo told authorities that about 7:30 p.m. August 3 his employer, Buddy Louden, telephoned to ask Wingo to go out drinking with him. The next day, Friday, was a workday, but Wingo consented.

After 11 p.m. the two men were at the 312 Club at 2701 East Lancaster Avenue.

After 11 p.m. the two men were at the 312 Club at 2701 East Lancaster Avenue.

If the name of the club confuses you, the 312 Club originally was located at 312 Henderson Street, then relocated to 506 West Magnolia Avenue and then to 2701 East Lancaster Avenue.

If the name of the club confuses you, the 312 Club originally was located at 312 Henderson Street, then relocated to 506 West Magnolia Avenue and then to 2701 East Lancaster Avenue.

At the 312 Club, Wingo later told authorities, he was sitting at a table with Louden when Wingo saw his ex-wife, Janice Ann, sitting at a table with Jimmy Clardy and Jack Mackin. Wingo approached his ex-wife and asked her how she was doing. Wingo recalled that Mrs. Wingo warned him that he had better leave the club or else there would be trouble.

At the 312 Club, Wingo later told authorities, he was sitting at a table with Louden when Wingo saw his ex-wife, Janice Ann, sitting at a table with Jimmy Clardy and Jack Mackin. Wingo approached his ex-wife and asked her how she was doing. Wingo recalled that Mrs. Wingo warned him that he had better leave the club or else there would be trouble.

Wingo said to her, “It’s a free country, and I can stay as long as I please.”

Wingo rejoined Louden at their table.

Clardy and Mackin walked over to the Wingo-Louden table and stood behind Wingo. Wingo told authorities that Mackin leaned on the table with his hands and said to Wingo: “I hear that you’re a real mean —.”

Wingo replied: “No, I don’t think so.”

Wingo recalled that Louden jumped up and scuffled with Clardy. The owner of the nightclub, Bob Rhodes, approached the table and at Wingo’s request asked Mackin and Clardy to return to their table.

Wingo said he and Louden left the nightclub shortly after it closed at midnight. Wingo and Louden got into Wingo’s Mercury sedan. As Wingo backed his car into the street, Wingo recalled, Clardy and Mackin came out the door of the nightclub and “hollered at us, and Buddy [Louden] hollered back at them.”

Wingo told authorities that Clardy or Mackin fired a pistol in the parking lot. As Wingo drove west on East Lancaster Avenue, Clardy and Mackin gave chase in Clardy’s 1955 Buick. After eight blocks Clardy and Mackin pulled alongside Wingo and Louden. Wingo told authorities that two gunshots came from the Clardy-Mackin car and that “Buddy slumped over in the seat and then fell onto the floorboards.”

Don Alvin Wingo was not charged with any crime.

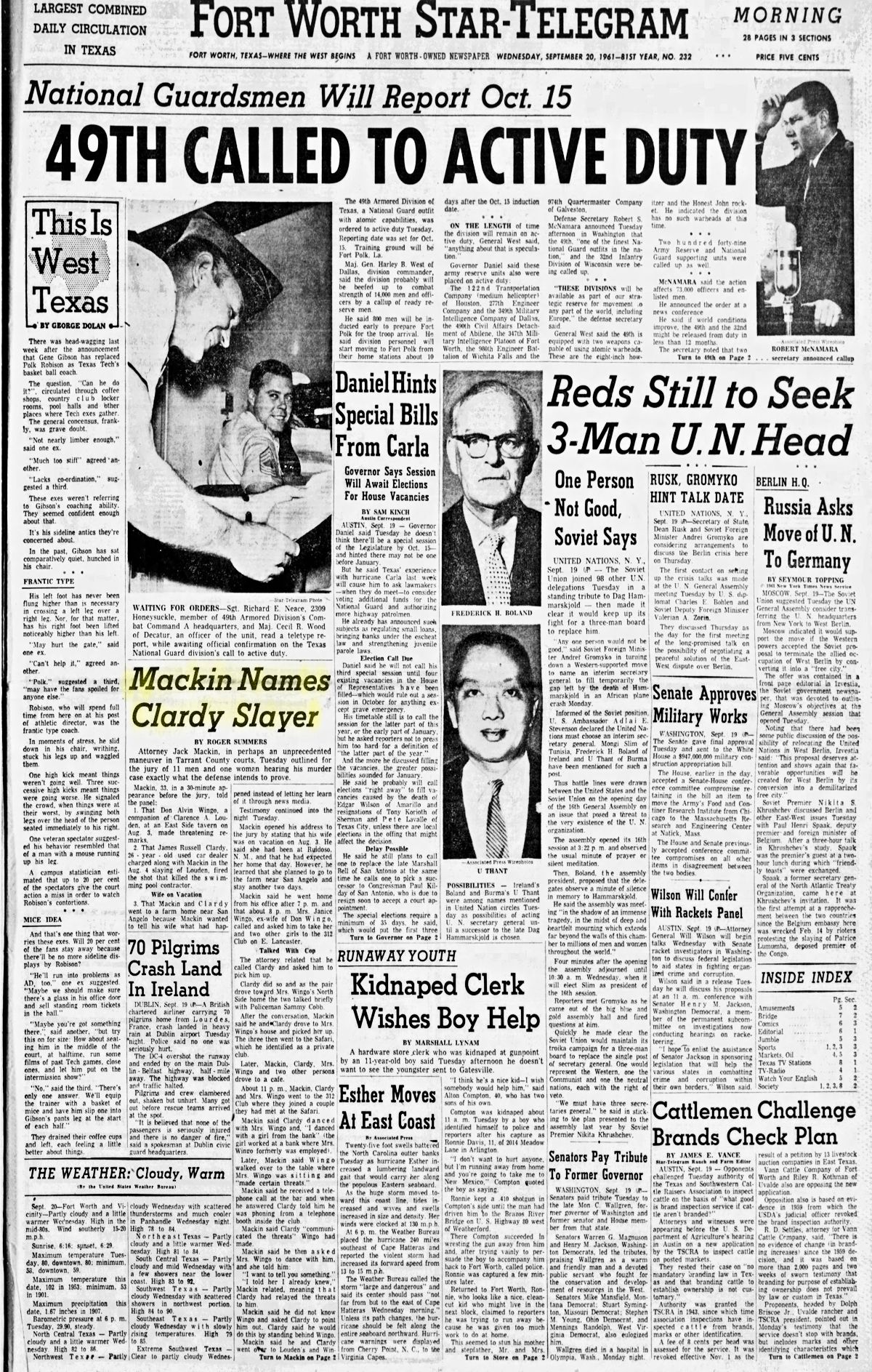

Jimmy Clardy admitted that he had fired the fatal gunshot. But under Texas law Jack Mackin was an accomplice and himself liable to a murder charge. Both men were charged with murder. District Attorney Doug Crouch said he would seek the death penalty in both cases.

When Jack Mackin went on trial for murder with malice in September 1961, he was represented by Clyde Mays, a prominent criminal defense attorney. But Mackin played an active role in his own defense. Mackin pleaded not guilty.

Mackin’s trial began with a hiccup during jury selection when Richard Abbott, a prospective juror who had known Jimmy Clardy since high school, reported that Clardy had asked him to claim during jury-selection questioning (1) that Abbott did not know Clardy and (2) that Abbott favored capital punishment if Mackin were convicted.

Clardy was charged with subornation of perjury.

During testimony Mackin took the witness stand and said that on the night of August 3 Mrs. Janice Wingo, ex-wife of Don Wingo, telephoned Mackin and asked him to escort her to a nightclub to meet other friends.

Mackin testified that his wife was out of town in their car, so he telephoned Jimmy Clardy and asked him to pick up Mackin and Mrs. Wingo. Mackin earlier had successfully defended Clardy in court on a minor charge.

Clardy picked up Mackin and Mrs. Wingo, and after drinking in two other nightclubs, the three went to the 312 Club after 11 p.m.

August 3 was a typical Texas blacktop-bubbler: The high temperature at Amon Carter Field was one hundred degrees. After 11 p.m. the temperature was still in the eighties.

Mackin testified that in the 312 Club, Wingo and his ex-wife talked while Mackin and Clardy were elsewhere in the club: Wingo asked his ex-wife if Mackin was the attorney who had advised her to have Wingo jailed for being behind in his child support payments.

Wingo said to Mrs. Wingo: “I’m going to get that bald-headed —- [Mackin] and the guy [Clardy] that’s with him.”

When the prosecution suggested to Mackin that he had a romantic relationship with Mrs. Wingo, Mackin admitted having visited Mrs. Wingo at her apartment several times but denied romantic involvement.

Mackin testified that in the 312 Club he and Clardy walked over to the Louden-Wingo table to confront Wingo about his “going to get” threat. Louden jumped to his feet, Mackin testified, and Clardy pinned Louden’s arms. Bob Rhodes, owner of the 312 Club, came over to see what the trouble was.

Mackin testified: “We [he and Clardy] didn’t want trouble, so we went back to our table.”

But, Mackin testified, he had feared that Louden or Wingo had a knife and asked Rhodes for a gun. Rhodes gave Mackin a .38-caliber pistol.

When the club closed at midnight, Wingo and Louden went outside. Soon after, Mackin and Clardy also went outside.

Across the street, gambler Tiffin Hall’s Mexican Inn Café was dark. Two miles to the west the revolving digital clock atop Continental National Bank read a few minutes past midnight.

On the parking lot Clardy and Louden again confronted each other. Louden asked Clardy if he wanted to “finish it now.”

Mackin testified that Louden hit Clardy on the face with a beer bottle and that when Louden reached as if to pick up another beer bottle, Mackin fired the pistol to warn Louden.

Wingo and Louden drove away, Mackin testified, and Mackin and Clardy followed. Clardy was driving. Mackin testified that he placed the pistol on the front seat between himself and Clardy.

Clardy and Mackin followed Wingo and Louden west on East Lancaster Avenue for eight blocks.

Mackin testified that as the two cars raced side by side, “Clardy made a statement to Mr. Louden” and Louden threw a beer bottle at Clardy’s car.

Mackin testified that Louden shouted, “You —-, I’ve got something that will stop you.”

Mackin continued: “The deceased [Louden] reached down and came up. Jim [Clardy] picked the gun up off the seat. I never picked it up. Jim came over with the gun and shot. When the shot was fired, he [Louden] went over. That’s the last I saw of him. As soon as the gun went off, Jim said, ‘God, I didn’t mean to shoot that man.’”

Mackin continued: “The deceased [Louden] reached down and came up. Jim [Clardy] picked the gun up off the seat. I never picked it up. Jim came over with the gun and shot. When the shot was fired, he [Louden] went over. That’s the last I saw of him. As soon as the gun went off, Jim said, ‘God, I didn’t mean to shoot that man.’”

On the witness stand Mackin was questioned by Assistant District Attorney J. Elwood (“Dutch”) Winters. Winters had prosecuted many murder defendants who faced life in prison or worse because of a single bad decision.

Winters asked Jack Mackin a crossroads question: “Why, when those boys [Wingo and Louden] left [the 312 Club], didn’t you take that gun back to Bob Rhodes?”

Mackin: “I wish to God a thousand times I had.”

Mackin’s trial ended in a hung jury.

Mackin’s trial ended in a hung jury.

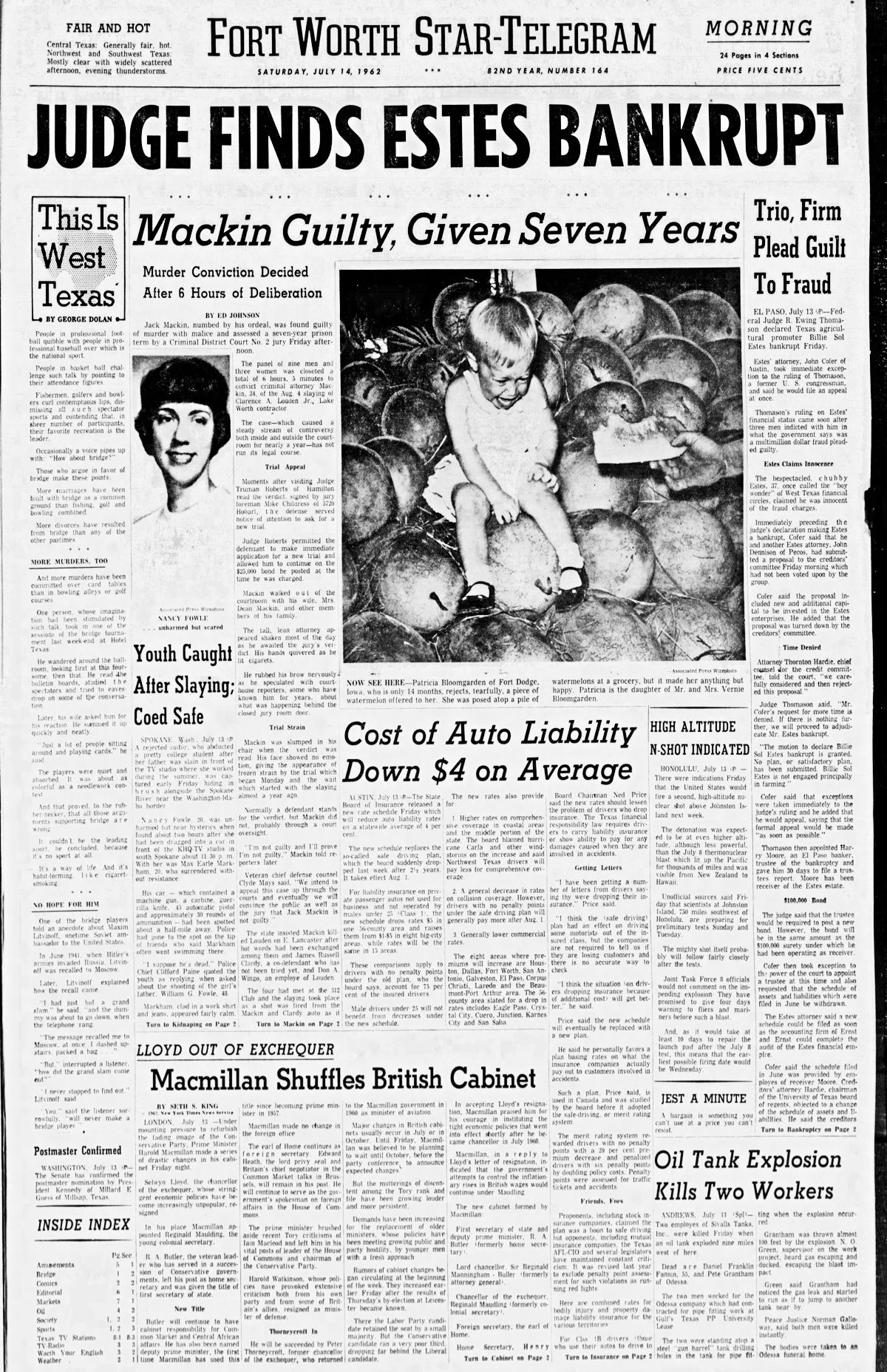

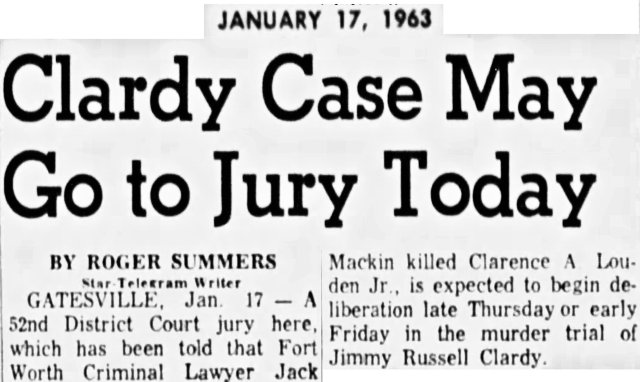

Jack Mackin was retried in July 1962. As testimony drew to a close, Mackin asked the judge for a fifteen-minute delay so Mackin could consider whether to rest his case or to testify in his own defense.

Mackin agonized over the decision, asking the advice of his defense attorneys, his law firm partners, his wife, even reporters.

Mackin rested his case without testifying.

Perhaps he made the right decision: Mackin faced a maximum penalty of death. After six hours of deliberation the jury found him guilty of murder with malice but sentenced him to only seven years in prison.

Perhaps he made the right decision: Mackin faced a maximum penalty of death. After six hours of deliberation the jury found him guilty of murder with malice but sentenced him to only seven years in prison.

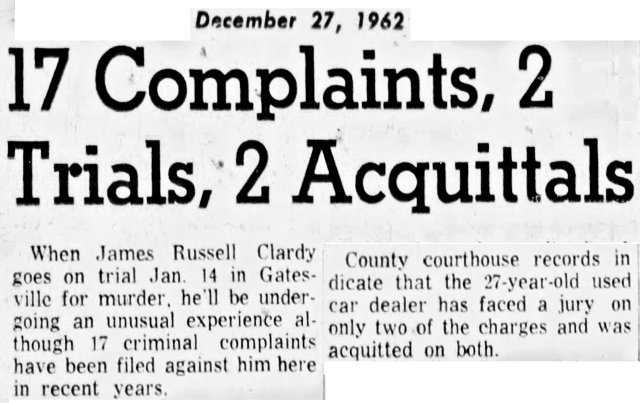

By the time James Russell Clardy went on trial for murder in 1963 he was well known to police. He was facing seventeen other charges ranging from violation of the Sunday closing law to destruction of private property after he was accused of driving a tank truck into a barber shop in 1960 during Fort Worth’s “barber shop war,” when members of the Texas Barber Association were accused of using strong-arm tactics—beatings, intimidation—to bring independent barbers into line with the hours and prices of TBA members.

By the time James Russell Clardy went on trial for murder in 1963 he was well known to police. He was facing seventeen other charges ranging from violation of the Sunday closing law to destruction of private property after he was accused of driving a tank truck into a barber shop in 1960 during Fort Worth’s “barber shop war,” when members of the Texas Barber Association were accused of using strong-arm tactics—beatings, intimidation—to bring independent barbers into line with the hours and prices of TBA members.

Jimmy Clardy had never been convicted.

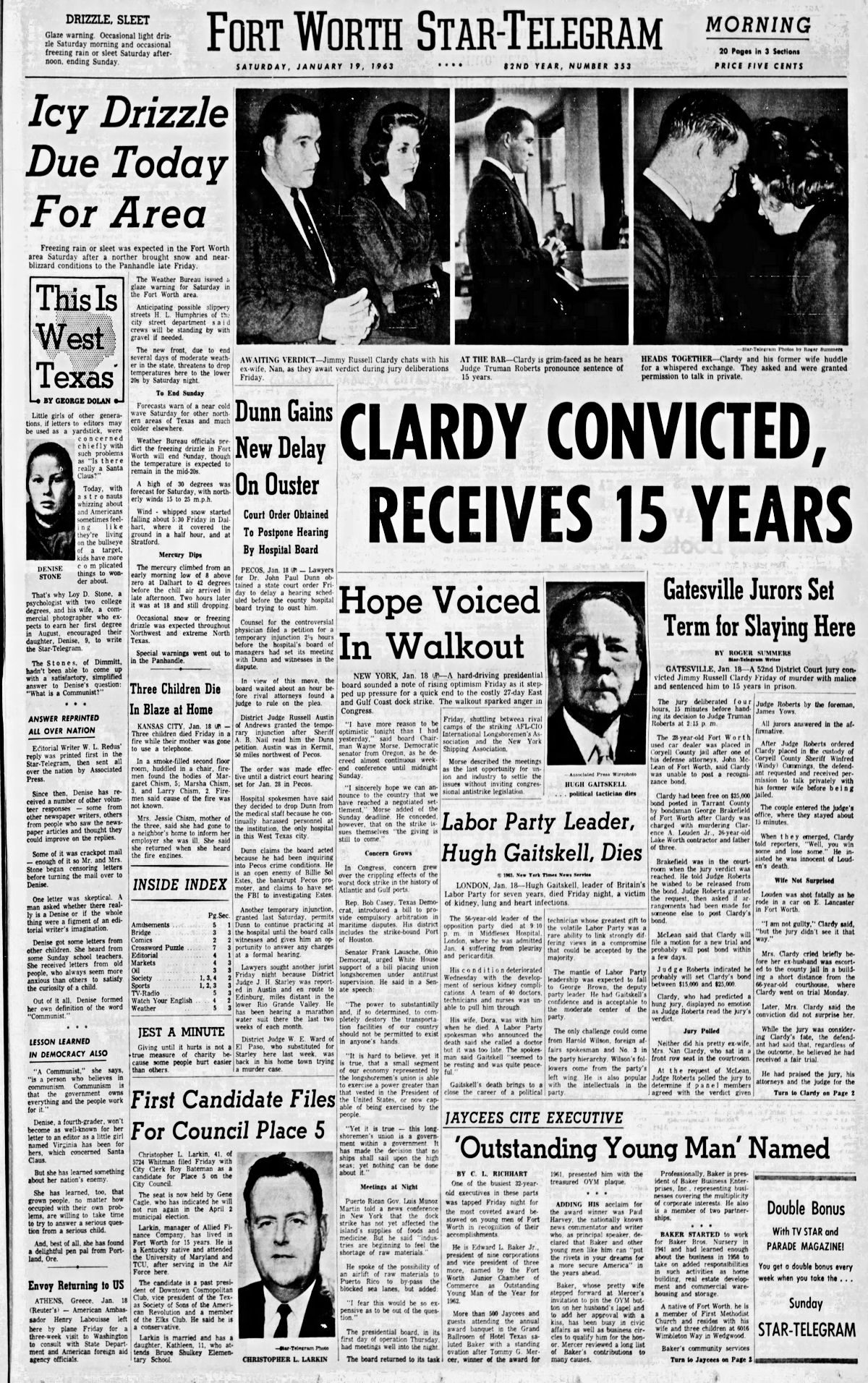

In January Clardy, pleading not guilty, took the witness stand to give his account of what happened on the night of August 3, 1961.

In January Clardy, pleading not guilty, took the witness stand to give his account of what happened on the night of August 3, 1961.

Clardy had filed for divorce from wife Nanola on August 2. He testified that the next day after 11 p.m. he and Jack Mackin had a tense confrontation with Don Wingo and Buddy Louden in the 312 Club. Later on the parking lot after midnight Louden hit Clardy on the face with a beer bottle. Louden and Wingo then drove away on East Lancaster Avenue. Clardy and Jack Mackin gave chase in Clardy’s car.

Clardy had filed for divorce from wife Nanola on August 2. He testified that the next day after 11 p.m. he and Jack Mackin had a tense confrontation with Don Wingo and Buddy Louden in the 312 Club. Later on the parking lot after midnight Louden hit Clardy on the face with a beer bottle. Louden and Wingo then drove away on East Lancaster Avenue. Clardy and Jack Mackin gave chase in Clardy’s car.

After Clardy and Mackin pulled alongside the Wingo-Louden car, Clardy testified, he yelled to Louden: “You could have knocked my eye out [with the beer bottle]!”

Clardy testified that Louden replied that he wished he had and asked Clardy if he wanted to pull to the curb and settle the dispute between them. Louden, Clardy testified, then threw a beer bottle at the Clardy-Mackin car.

Then, Clardy testified, he saw Louden reach down to the floorboard, come up, look toward the Clardy-Mackin car, and shout, “I have something that will stop you!”

With that, Clardy testified, Jack Mackin picked up the pistol he had borrowed from 312 Club owner Rhodes and shot Louden. Clardy testified that he had not known that Mackin planned to shoot Louden. Clardy contended that he had intended to stop the car and settle his dispute with Louden with fists.

Clardy admitted to the jury that he originally had confessed that he, not Mackin, had shot Louden. He now testified that he had made the confession on Mackin’s advice.

“He [Mackin] told me that we were in pretty serious trouble—that the only way we both could get out of it was for me to say I did it,” Clardy testified: Mackin had promised to get himself acquitted first, then get Clardy acquitted, Clardy testified.

“I just took him at his word,” Clardy said.

The first part of Mackin’s plan had failed. Now James Russell Clardy was on his own.

As Assistant District Attorney Dutch Winters questioned Clardy, Winters asked Clardy a crossroads question, just as he had asked Jack Mackin earlier: Why had Clardy not simply let his confrontation with Buddy Louden end in the parking lot of the 312 Club instead of chasing Louden and Wingo down Lancaster Avenue?

Clardy’s reply: “I wish I had.”

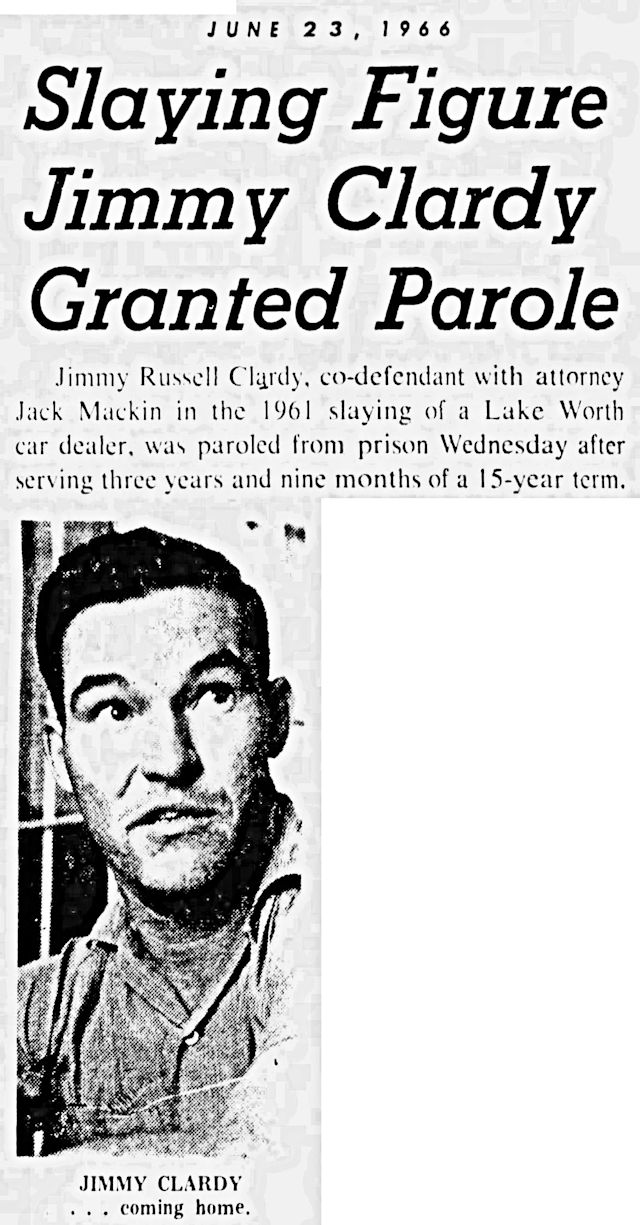

Clardy was found guilty of murder with malice and sentenced to fifteen years in prison.

Clardy was found guilty of murder with malice and sentenced to fifteen years in prison.

End of story, right? One murder, two convictions.

But for James Russell Clardy, the violence did not end with the murder of Buddy Louden.

In June 1963 Clardy was free on bond pending appeal of his conviction. On the afternoon of June 24 a motorist on Ten-Mile Bridge Road south of Eagle Mountain Lake saw a bloody man dragging himself alongside the roadside. The man’s spinal cord had been severed. He was paralyzed from the waist down.

In June 1963 Clardy was free on bond pending appeal of his conviction. On the afternoon of June 24 a motorist on Ten-Mile Bridge Road south of Eagle Mountain Lake saw a bloody man dragging himself alongside the roadside. The man’s spinal cord had been severed. He was paralyzed from the waist down.

Jimmy Clardy later told his story from a hospital bed: Ray Crane, a used car salesman, had offered Clardy money to kill ex-convict George Edward Daltwas. Daltwas was the ex-husband of Crane’s wife and had been giving Crane “considerable trouble.” Clardy declined the job offer. After that, he said, Crane suspected (1) that Clardy had warned Daltwas that Crane wanted him dead and (2) that Clardy and Daltwas planned to retaliate against Crane.

So, Crane, with Gary Martin and Johnny Guerrero, abducted Clardy at gunpoint and drove him to Ten-Mile Bridge Road, where, Crane and Guerrero told Clardy, they were going to “wipe him out.”

Clardy said Crane and Guerrero escorted him into a pasture and shot him three times. A .38-caliber bullet in the back severed his spine. Two Derringer bullets shattered his jaw.

Clardy was left for dead.

District Attorney Crouch and Sheriff Lon Evans were skeptical of Clardy’s story, suspected that the motive of Crane and Guerrero ran “deeper.”

District Attorney Crouch and Sheriff Lon Evans were skeptical of Clardy’s story, suspected that the motive of Crane and Guerrero ran “deeper.”

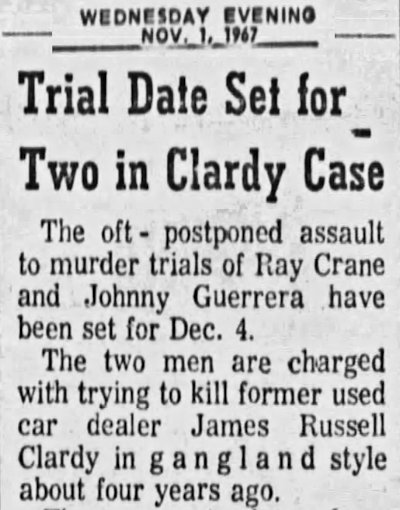

Nonetheless, Crane and Guerrero were indicted for assault to murder.

And what would a story about Fort Worth crime be without a front-page photo of a policeman wearing a gas mask and holding a tear-gas gun and a poodle?

And what would a story about Fort Worth crime be without a front-page photo of a policeman wearing a gas mask and holding a tear-gas gun and a poodle?

On August 15 George Edward Daltwas—whom Jimmy Clardy had declined to kill—was charged with assault with intent to rape. A warrant for his arrest was issued. Three days later two Lake Worth custodians went to his house on the lake. Someone in the house fired a shotgun blast over the two custodians. More than a dozen Fort Worth police officers surrounded the house and fired tear gas into it during a three-hour siege after which the only inhabitants of the house were found to be . . . two poodles.

Police found a recently fired shotgun on the beach behind the Daltwas home. Daltwas said he had been swimming in the lake at the time the shotgun was fired but denied firing it.

He was arrested.

Fast-forward three years. In 1966 Jimmy Clardy was paroled after serving three years and nine months of his fifteen-year sentence for murdering Buddy Louden.

Fast-forward three years. In 1966 Jimmy Clardy was paroled after serving three years and nine months of his fifteen-year sentence for murdering Buddy Louden.

Paralyzed below the waist, Clardy resumed selling used cars. He lived with his mother and two brothers.

Paralyzed below the waist, Clardy resumed selling used cars. He lived with his mother and two brothers.

Meanwhile, Jack Mackin worked as a teacher and trusty in prison. He was proud of having helped seven hundred young prisoners graduate from high school while incarcerated. Mackin continued to contend that Jimmy Clardy had killed Buddy Louden.

Meanwhile, Jack Mackin worked as a teacher and trusty in prison. He was proud of having helped seven hundred young prisoners graduate from high school while incarcerated. Mackin continued to contend that Jimmy Clardy had killed Buddy Louden.

In 1964 Tarrant County District Attorney Doug Crouch had recommended that Mackin’s sentence be commuted to two years after Mackin was given a polygraph test that convinced Crouch that Jimmy Clardy, not Mackin, had killed Louden.

Mackin was paroled in 1967.

In November 1967 the Star-Telegram announced that the long-postponed trial of Ray Crane and Johnny Guerrero was scheduled to begin. But as of late 1968—more than five years after Jimmy Clardy was shot and left for dead—Crane and Guerrero still had not stood trial, perhaps because Clardy would not testify against them. I can find no resolution of the case.

In November 1967 the Star-Telegram announced that the long-postponed trial of Ray Crane and Johnny Guerrero was scheduled to begin. But as of late 1968—more than five years after Jimmy Clardy was shot and left for dead—Crane and Guerrero still had not stood trial, perhaps because Clardy would not testify against them. I can find no resolution of the case.

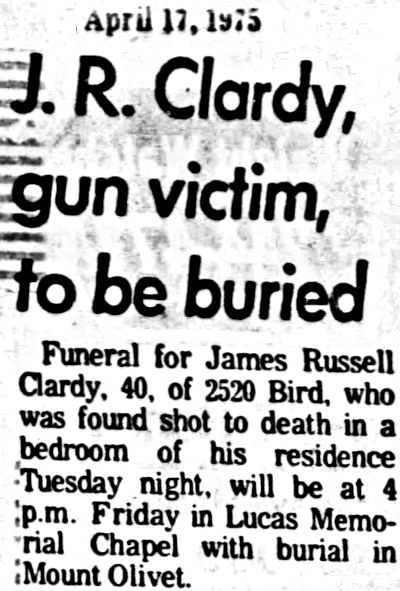

For James Russell Clardy, the violence did not end with the murder of Buddy Louden in 1961 and the attempted murder of Clardy himself in 1963.

For James Russell Clardy, the violence did not end with the murder of Buddy Louden in 1961 and the attempted murder of Clardy himself in 1963.

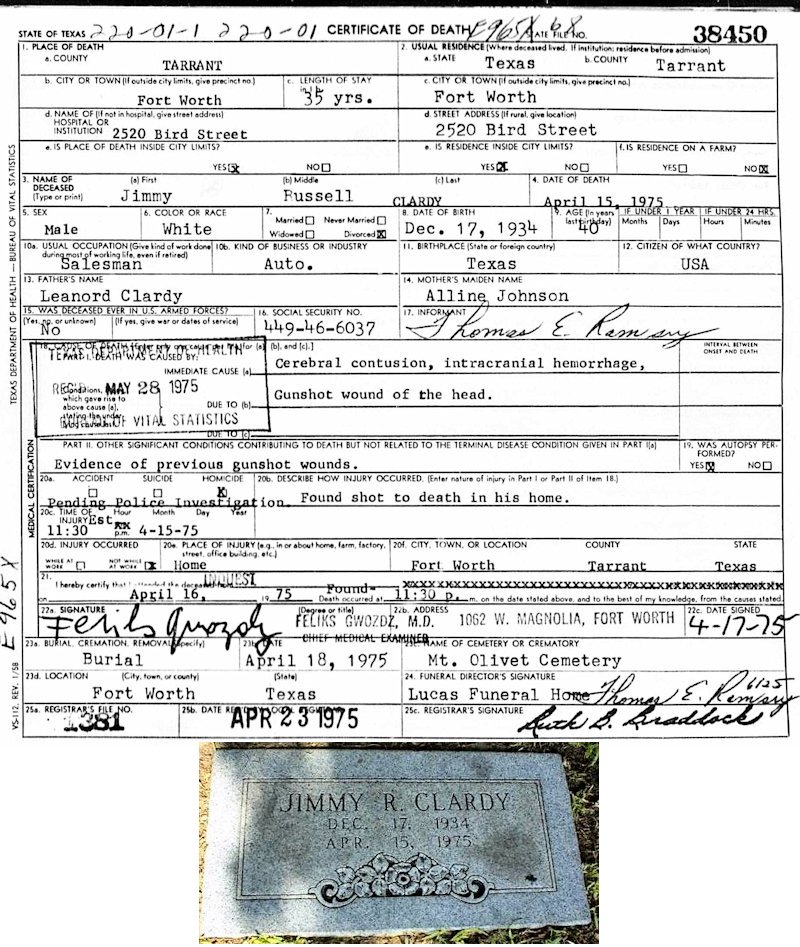

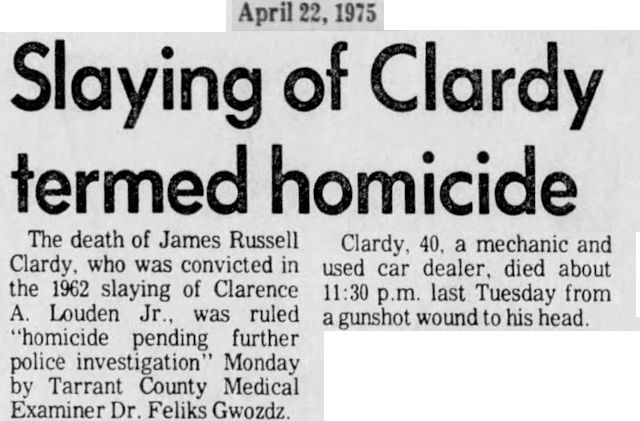

In 1975 Clardy was found shot to death in his bedroom. His son and mother reported hearing what sounded like a gunshot about ten minutes before the son found his father’s body, police said. Police found a recently fired rifle in another room of the house.

James Russell Clardy is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

James Russell Clardy is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

Clardy’s death was ruled a homicide.

Clardy’s death was ruled a homicide.

Clardy’s son Russell was charged with murder. Fort Worth police detective Oliver Ball said “friction” existed between father and son.

Clardy’s son Russell was charged with murder. Fort Worth police detective Oliver Ball said “friction” existed between father and son.

Another loose end: I can find no resolution of the murder of James Russell Clardy.

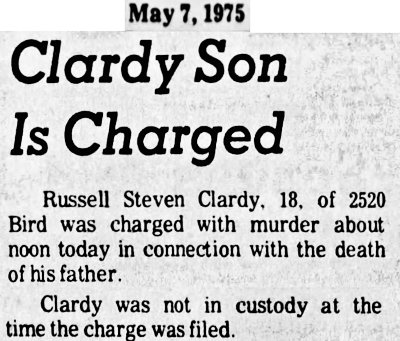

Jack Mackin, paroled but disbarred and dragging a murder conviction like a ball and chain, reinvented himself as a contract administrator for LTV. He died in 1992 in Palo Pinto County.

Jack Mackin, paroled but disbarred and dragging a murder conviction like a ball and chain, reinvented himself as a contract administrator for LTV. He died in 1992 in Palo Pinto County.

And what of the fourth man who stood at the crossroads on a hot summer night in 1961? In January 1962 Don Alvin Wingo put his ex-wife, the 312 Club, and August 3 behind him and married Betty Jo Alexander. He worked for General Motors in Arlington for thirty-two years. Don Alvin and Betty Jo were married until death them did part in 2004.

And what of the fourth man who stood at the crossroads on a hot summer night in 1961? In January 1962 Don Alvin Wingo put his ex-wife, the 312 Club, and August 3 behind him and married Betty Jo Alexander. He worked for General Motors in Arlington for thirty-two years. Don Alvin and Betty Jo were married until death them did part in 2004.

(Thanks to Shirley Enis for the tip.)

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade

Ray Crane is my grandfather and from what I’ve been told, there was no resolution of the case because Ray bribed a judge with a watch. It’s also not at all the story he told my father. We didn’t know the real story until I found this. This is also not the only crime he committed but there’s no proof of the others.

Had no idea he’d been involved in so much crime, but think he did have a good side he displayed around us! Thanks for the article!

Turned into quite a roller-coaster of a story.