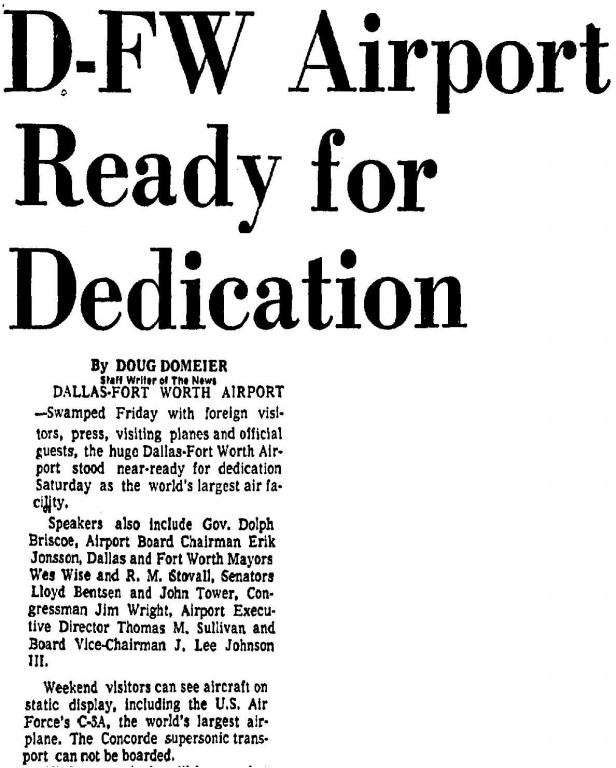

Picture this: The time is 1887. July 3. The scene is the open range of far west Texas. A rancher in that desolate area is driving his buckboard wagon full of supplies toward home. Perhaps he is driving too fast; perhaps he has been drinking. Perhaps the front wagon wheels hit a rut; perhaps the wagon’s load shifts, and the rancher lunges to save a sack of grain from falling and rupturing. Either way, the rancher is thrown from the wagon. He is falling, falling, falling toward the ground directly in the path of the wagon wheels, and . . . freeze frame! Quick: Before the rancher hits the ground, fast-forward eighty-six years. The time is 1973. The scene is the dedication of Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport. What we see hit the ground is not the west Texas rancher but rather the screeching, smoking tires of the Concorde supersonic jet.

What connections could there be between that wagon accident in west Texas in 1887 . . .

What connections could there be between that wagon accident in west Texas in 1887 . . .

and the opening of the airport in 1973? In the years between these two events, a dead west Texas rancher grew into a legend, two little girls grew into social prominence, and Fort Worth grew into a city. The connections tell a story of the old West and the new West, of saloons and salons, of a quarter-century of one man’s violence and a century of one family’s business success and community service.

and the opening of the airport in 1973? In the years between these two events, a dead west Texas rancher grew into a legend, two little girls grew into social prominence, and Fort Worth grew into a city. The connections tell a story of the old West and the new West, of saloons and salons, of a quarter-century of one man’s violence and a century of one family’s business success and community service.

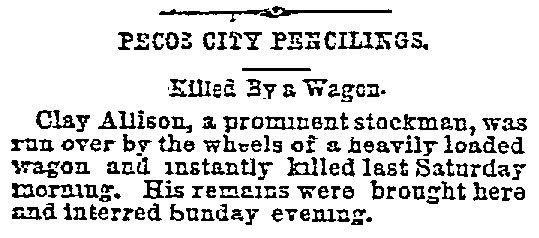

Some background: The 1887 news story above describes Clay Allison as just “a prominent stockman,” but, yes, that prominent stockman was the Clay Allison.

Some background: The 1887 news story above describes Clay Allison as just “a prominent stockman,” but, yes, that prominent stockman was the Clay Allison.

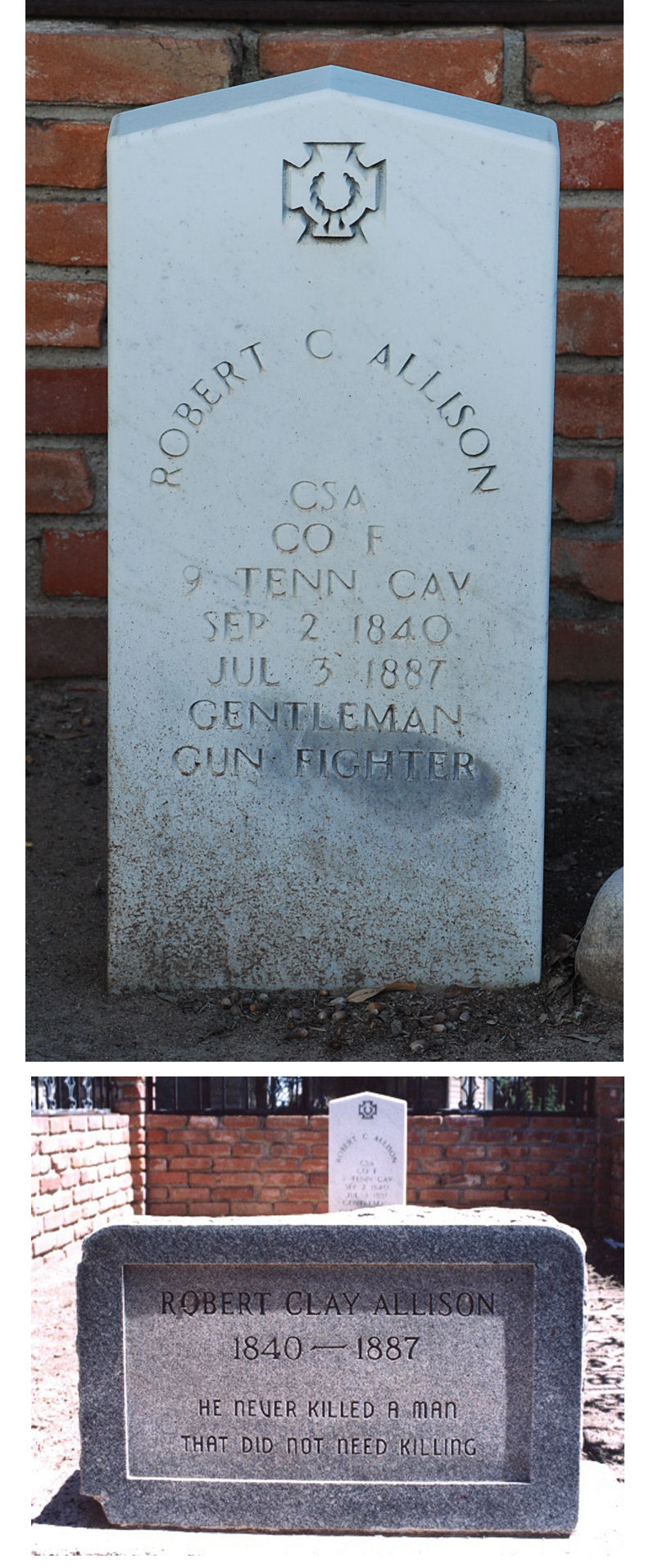

As always with legends, sorting fact and fable is difficult. Many claims have been made about Robert Clay Allison. Did he really refer to himself as a “shootist”? Did he say he “never killed a man that did not need killing”? Did he once ride through the town of Mobeetie, Texas, wearing only a gunbelt while declaring that drinks were on him at the saloon? Did he really shoot out the lights of saloons and insist that his horse be served whiskey at the bar? Did Allison and a neighbor settle an argument by engaging in a knife fight in an open grave? Did Allison yank a tooth out of the mouth of a dentist who had pulled the wrong tooth out of Allison’s mouth? Did Allison once decapitate a man whom Allison had already helped to lynch? Did he once eat a meal with a man before shooting the man because Allison “didn’t want to send a man to Hell on an empty stomach”? Did he blow up a newspaper office in Cimarron, New Mexico, after the paper accused him of inciting violence?

As always with legends, sorting fact and fable is difficult. Many claims have been made about Robert Clay Allison. Did he really refer to himself as a “shootist”? Did he say he “never killed a man that did not need killing”? Did he once ride through the town of Mobeetie, Texas, wearing only a gunbelt while declaring that drinks were on him at the saloon? Did he really shoot out the lights of saloons and insist that his horse be served whiskey at the bar? Did Allison and a neighbor settle an argument by engaging in a knife fight in an open grave? Did Allison yank a tooth out of the mouth of a dentist who had pulled the wrong tooth out of Allison’s mouth? Did Allison once decapitate a man whom Allison had already helped to lynch? Did he once eat a meal with a man before shooting the man because Allison “didn’t want to send a man to Hell on an empty stomach”? Did he blow up a newspaper office in Cimarron, New Mexico, after the paper accused him of inciting violence?

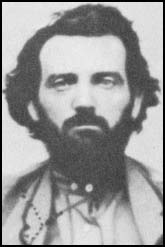

Who knows for sure? This much is known: Robert Clay Allison, the son of a Presbyterian minister, was discharged from the Confederate Army because of a “partly epileptic and partly maniacal” condition. After the Civil War he drifted: New Mexico, Colorado, Missouri, Dodge City. He drove cattle herds for Charles Goodnight and Oliver Loving, belonged to the Ku Klux Klan. And he fought. With pistol and knife. By the time he fell under that wagon wheel at age forty-seven, he had killed six men. Or fifteen. Or twenty. The body count varies among sources. One thing is certain: Allison was democratic. He killed lawmen and lawless men alike. Law enforcement was not stringent in the time and place of Clay Allison. On those occasions when he killed a man and faced charges, a plea of self-defense was successful.

Like Luke Short, Clay Allison is hard to pigeonhole. Both “gentleman” and “gun fighter,” Allison’s tombstone says. He was indeed a “prominent stockman,” eventually a family man, even an anonymous benefactor of those in need, some said. And like Short, Allison claimed to not be the instigator of the violence that shadowed him. But like Short, Allison seldom backed away from violence. One difference between the two men: Short gambled; Allison drank. A decent citizen when sober, when drunk Allison was the devil in a duster.

One man who knew Allison said: “He was a whale of a good fellow and considerate of his fellow men, but throw a drink or two into him, and he was a hellhound turned loose, rearin’ for a chance to shoot—in self-defense.”

Upon Allison’s death the Ford County Globe in Dodge City wrote: “Clay knew no fear. To incur his enmity was equivalent to a death sentence. He contended that he never killed a man willingly, but out of necessity. He was an expert with his revolvers and never failed to come out best in a deadly encounter.”

By 1880 Allison was ranching near Mobeetie in the Texas Panhandle. There we find our first connection:

In 1881 Allison married Medora (“Dora”) McCulloch from Sedalia, Missouri. Dora was twenty-two years younger. By some accounts Dora had a calming effect on Allison. Certainly reports of his violence declined in the 1880s. By 1883 Allison and Dora were ranching near Pecos in far west Texas.

In 1881 Allison married Medora (“Dora”) McCulloch from Sedalia, Missouri. Dora was twenty-two years younger. By some accounts Dora had a calming effect on Allison. Certainly reports of his violence declined in the 1880s. By 1883 Allison and Dora were ranching near Pecos in far west Texas.

In 1885 daughter Patti Dora Allison was born. Patti would know her father only two years. When Clay Allison was killed in 1887, Patti’s mother was pregnant with Patti’s sister-to-be. Clay Allison’s namesake daughter, Clay Pearl Allison, was born seven months after her father died.

While the widowed Dora cared for her two young daughters, the legend of her dead husband grew.

While the widowed Dora cared for her two young daughters, the legend of her dead husband grew.

But even as Clay Allison’s legend grew, this 1889 clip shows the old West already being spoken of in past tense.

But even as Clay Allison’s legend grew, this 1889 clip shows the old West already being spoken of in past tense.

In 1890—the year the western frontier was declared closed—Clay Allison’s widow remarried. Her new husband was our next connection: Jesse Lee Johnson (pictured). Johnson, born in Brenham in 1862, was a sheepherder and then a merchant and lumberman in Pecos, Texas. In 1897 Jesse Lee Johnson moved Dora, stepdaughters Patti and Clay, and their son, Jesse Lee Jr. (born 1891), to Fort Worth to begin a new life far from the grave of the “gentleman gun fighter”:

In 1890—the year the western frontier was declared closed—Clay Allison’s widow remarried. Her new husband was our next connection: Jesse Lee Johnson (pictured). Johnson, born in Brenham in 1862, was a sheepherder and then a merchant and lumberman in Pecos, Texas. In 1897 Jesse Lee Johnson moved Dora, stepdaughters Patti and Clay, and their son, Jesse Lee Jr. (born 1891), to Fort Worth to begin a new life far from the grave of the “gentleman gun fighter”:

Connections: From Buckboard to Concorde (Part 2)

Posts About Fort Worth’s Wild West History

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade

Throw it in reverse to 1984 and you wore your hair just like Mr. Allison. No mullet on Mr. Nichol’s head…No, Sir. Those were your “okeydokey” days.