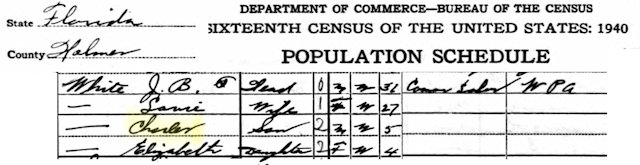

Charles William (“Bill”) White was born in 1934 in the Florida Panhandle to James B. and Lovie White.

Charles William (“Bill”) White was born in 1934 in the Florida Panhandle to James B. and Lovie White.

Father James B. White in 1940 was a common laborer with the federal Works Progress Administration.

Father James B. White in 1940 was a common laborer with the federal Works Progress Administration.

There would be nothing common about his son’s labor.

Bill was injured at age nine when a blasting cap exploded in his hand. Several surgeries were necessary to save his eyesight. After that Bill seemed to live like there was no tomorrow: He wrestled alligators for tourist dollars. He performed airplane wing walking, trick parachuting, and trick motorcycle riding. He ran moonshine.

In 1964 White met Herbert (“Digger”) O’Dell Smith, who was a “professional endurance man” who had begun his career as a flagpole sitter and then had gone in the other direction: being buried in a plywood coffin, usually as a publicity stunt for a car dealership or other business.

Smith had just finished spending forty-eight days buried in a plywood coffin in Alabama.

When White met Smith, the following exchange occurred (I am paraphrasing):

White: Hah! I could stay buried in a coffin longer than forty-eight days.

Smith: No way, Mac.

White: Hold my shroud.

And so the man who had lived like there was no tomorrow began to die like there was no tomorrow.

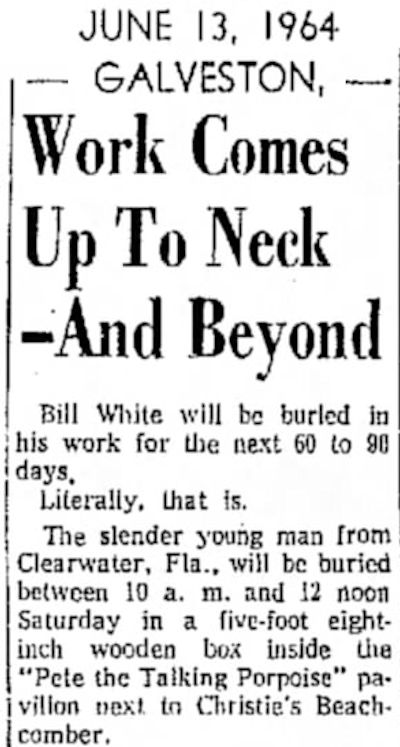

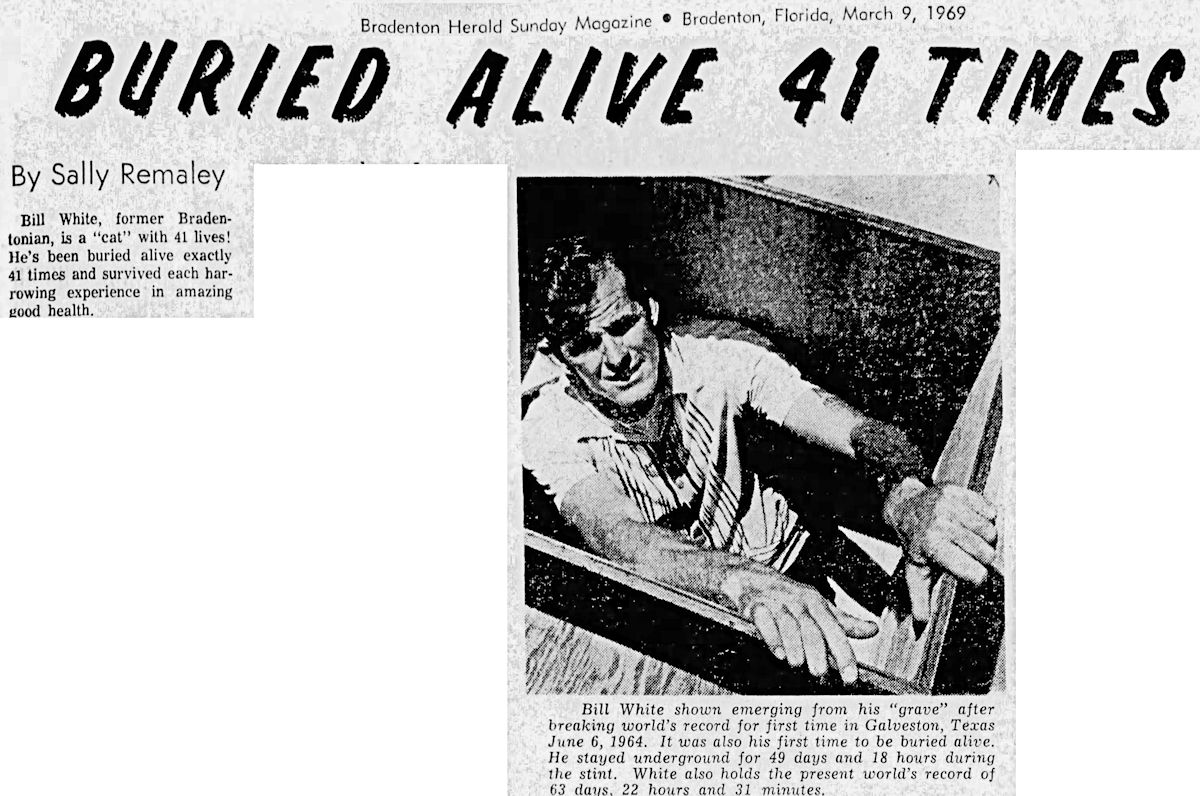

Bill White procured a sponsor—Christie’s Beachcomber restaurant in Galveston—and had himself buried in the sand on the beach. His next-door-neighbor was Pete the talking porpoise.

Bill White procured a sponsor—Christie’s Beachcomber restaurant in Galveston—and had himself buried in the sand on the beach. His next-door-neighbor was Pete the talking porpoise.

White, who was five-foot-eleven, was buried in a coffin that was five feet eight inches long.

As he began his burial he said that only cramps could cause him to emerge before he broke Smith’s record.

“If they get so bad I can’t stand it, then I will have to come up. Remember, I can’t stretch out to my full length.”

White was connected to the outside world by a shaft that provided him with air, a microphone, and a telephone. He answered phone calls from his followers. The lid of his coffin had a clear viewing panel so that people could look down the shaft and see White.

White stayed in his coffin for forty-nine days, breaking Digger O’Dell’s record.

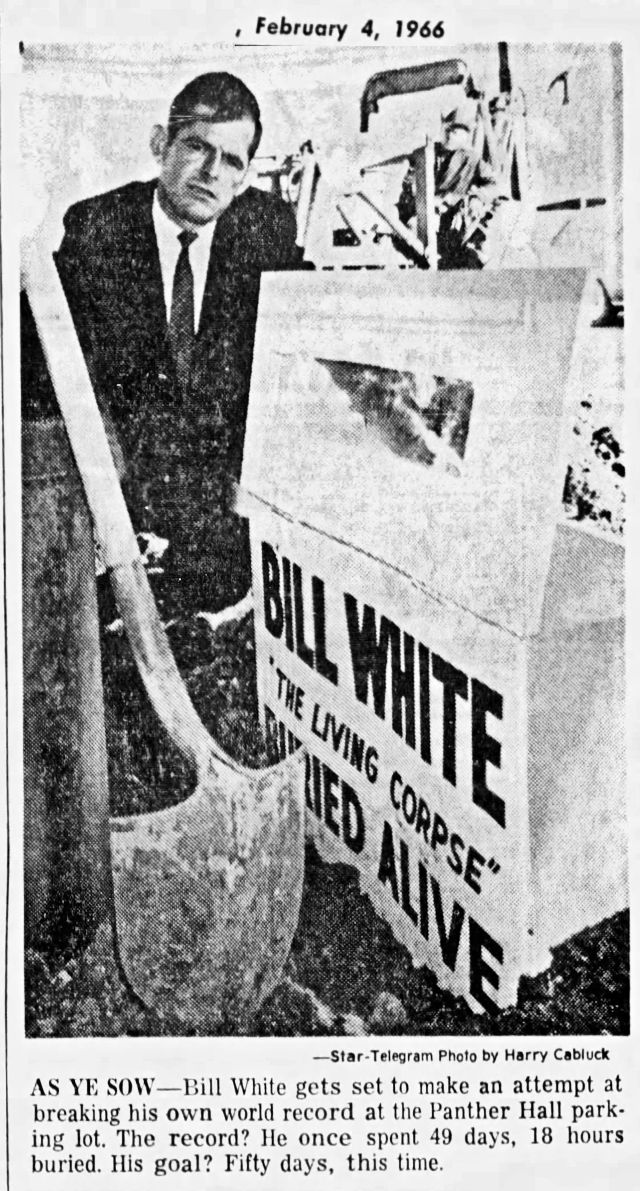

Fast-forward to 1966. White was now a resident of Fort Worth. After the success of his Galveston burial, he had turned dying into a living. He had burials scheduled in major cities across the state in the coming months.

White had refined his act: He now billed himself as “the Living Corpse.” Atop his grave at each burial was a simulated tombstone with flowers. His plywood coffin was a bit roomier now (thirty-two inches high and wide, six feet long). Food could be delivered to him via his airshaft. He followed a diet recommended by a physician. He did isometric exercises to stay fit.

On February 2, 1966 White was buried in the parking lot of Panther Hall on East Lancaster Avenue.

On February 2, 1966 White was buried in the parking lot of Panther Hall on East Lancaster Avenue.

His goal: To stay down fifty days and break his own record.

The first couple of days would be the hardest, he said, because as the dirt settles over the coffin, the coffin “creaks and pops and . . . makes you nervous.”

“I’ll only sleep a couple of hours a day and eat about two meals.”

Dear reader, I know that just about now you have a question: “How about . . . well, you know . . . plumbing?”

For which White had a non-answer: “Not even my daddy knows about that. That’s the secret. If that ever gets out, anyone could set the record.”

To pass the time, White had with him a transistor radio. But most of his time underground was spent talking on the telephone. In fact, two telephones: One was reserved for giving interviews to the news media. On the other phone he talked with people from all over the country (his phone number was included in ads promoting his burial). The average interval between calls, he estimated, was seven seconds. White answered each call with a cheery “the Living Corpse.”

“You meet some interesting people over the telephone,” he said. Most of his callers were merely curious, but some were lonely and wanted someone to talk with.

Most of his callers were women.

And that was Cupid’s cue.

As White lay six feet below the Panther Hall parking lot, he was about to begin a romance the likes of which had never been sung about by any balladeer on any country-western stage.

One woman in particular began to telephone White. First she called during the day. Then she began to call at night.

Her voice was pleasing to White.

He found himself looking forward to her calls.

White recalled: “The girl told me her name was ‘Lottie Howard.’ More and more keenly I anticipated her phone calls. And though I couldn’t see her, I soon knew I was in love.”

That love was reciprocated by the young Fort Worth secretary he had never seen.

One night, still in his Panther Hall grave, White proposed marriage—his third—to the voice on the phone.

The voice accepted, and Lottie Howard was waiting for White when, after twenty-four days underground, White cut short his burial and surfaced in the name of love.

When he met Lottie, he liked what he saw as well as what he had heard.

Yes, love was in the air, but Bill White had places to go and coffins to fill.

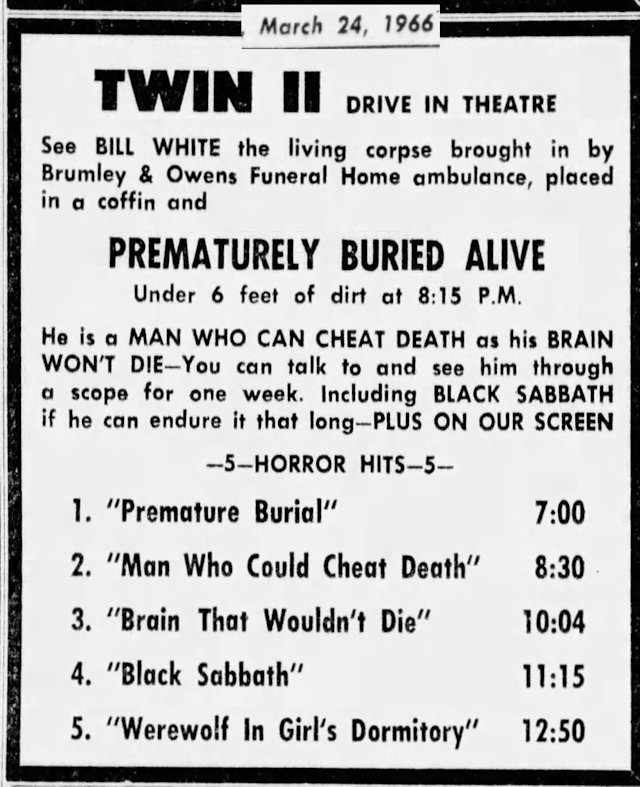

On March 24 an Owens & Brumley ambulance delivered White and his coffin to the Twin drive-in theater to begin his next burial.

On March 24 an Owens & Brumley ambulance delivered White and his coffin to the Twin drive-in theater to begin his next burial.

After four days below ground White told Star-Telegram entertainment columnist Elston Brooks that he had smoked four packs of cigarettes and missed several of his favorite television programs.

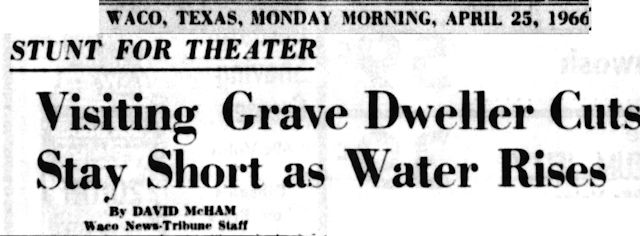

From Fort Worth White went to Waco to begin his twelfth burial—at another drive-in theater. But his premature burial was ended prematurely when heavy rain seeped into his coffin, and an emergency exhumation was necessary lest the living corpse become the for-real corpse.

From Fort Worth White went to Waco to begin his twelfth burial—at another drive-in theater. But his premature burial was ended prematurely when heavy rain seeped into his coffin, and an emergency exhumation was necessary lest the living corpse become the for-real corpse.

This was not the first time White had encountered an occupational hazard. During one burial his coffin lid had caved in from the weight of the dirt on it. During another burial he had run out of air, and rescue workers lowered an oxygen mask to him as they dug to free him.

“That was the nearest I ever came to panic,” White recalled.

His coffin was not entirely verminproof.

“Every once in a while the bugs and lizards get in. I find deodorant spray works. A little Right Guard drives ’em right out.”

And his coffin was not serpentproof. Once a woman dropped her pet snake—a six-foot boa constrictor—down White’s airshaft. That encounter did not end well.

For the snake.

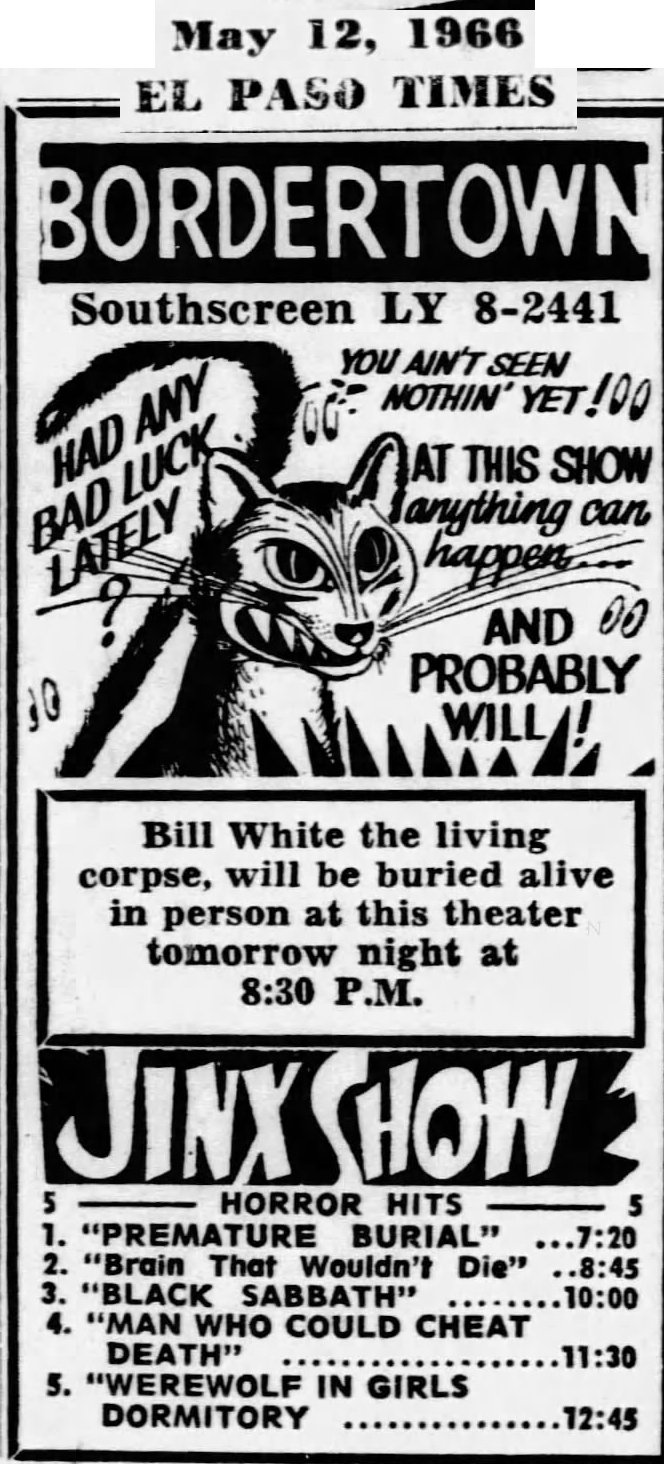

After the Waco washout, White was off to El Paso. On Friday, May 13 he arrived by ambulance at the Bordertown drive-in theater. The public was invited to help fill in the grave over his coffin. The theater presented horror movies on Friday 13 and teen dances on Saturday and Sunday. White selected the records, acting as DJ (death jockey).

After the Waco washout, White was off to El Paso. On Friday, May 13 he arrived by ambulance at the Bordertown drive-in theater. The public was invited to help fill in the grave over his coffin. The theater presented horror movies on Friday 13 and teen dances on Saturday and Sunday. White selected the records, acting as DJ (death jockey).

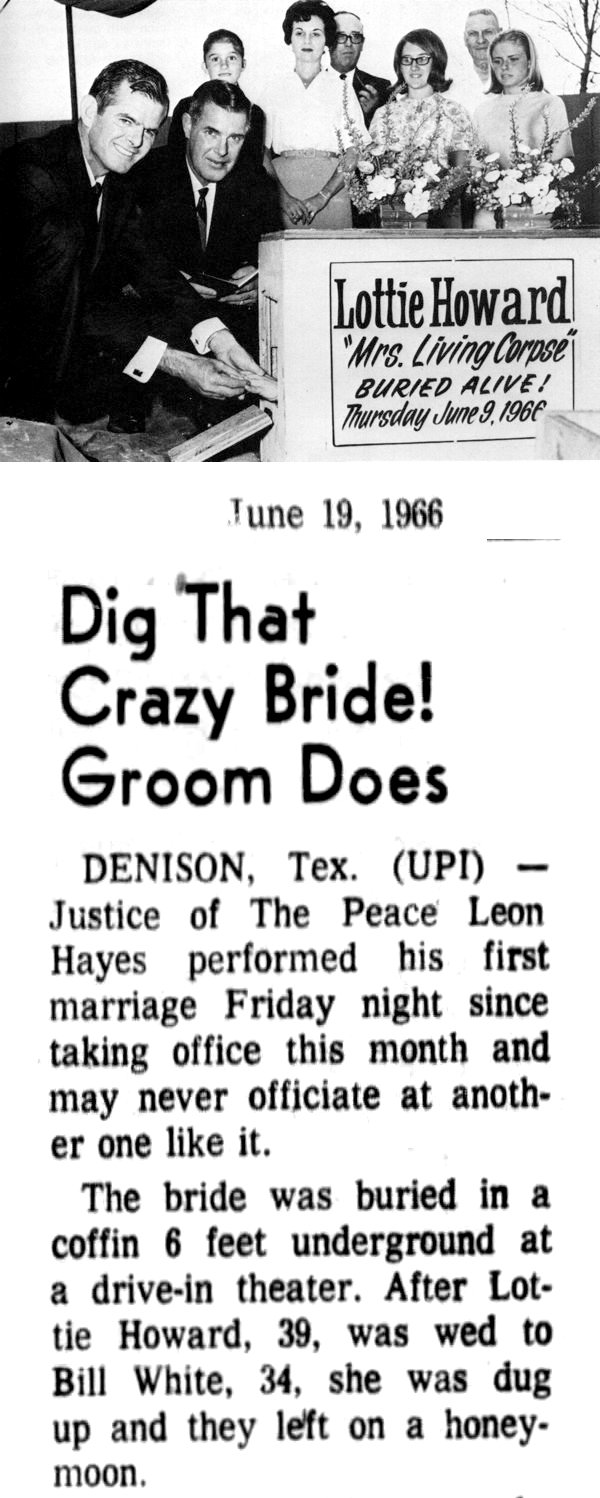

By June 1966 Bill White finally had enough free time above ground to turn his thoughts to marriage. But his betrothed felt it only fair that first she experience something of her fiance’s deathly livelihood.

By June 1966 Bill White finally had enough free time above ground to turn his thoughts to marriage. But his betrothed felt it only fair that first she experience something of her fiance’s deathly livelihood.

So, Lottie Howard had herself buried at a drive-in theater in Denison. After a week underground, she stuck her hand through a slot above her coffin, Bill White slipped a ring on her finger, and a justice of the peace—conducting his first marriage ceremony—declared Bill and Lottie to be “Mr. and Mrs. Living Corpse.”

Lottie was then dug up, the newlyweds had a two-week honeymoon, and Bill went on to San Antonio to begin life as a married buried man.

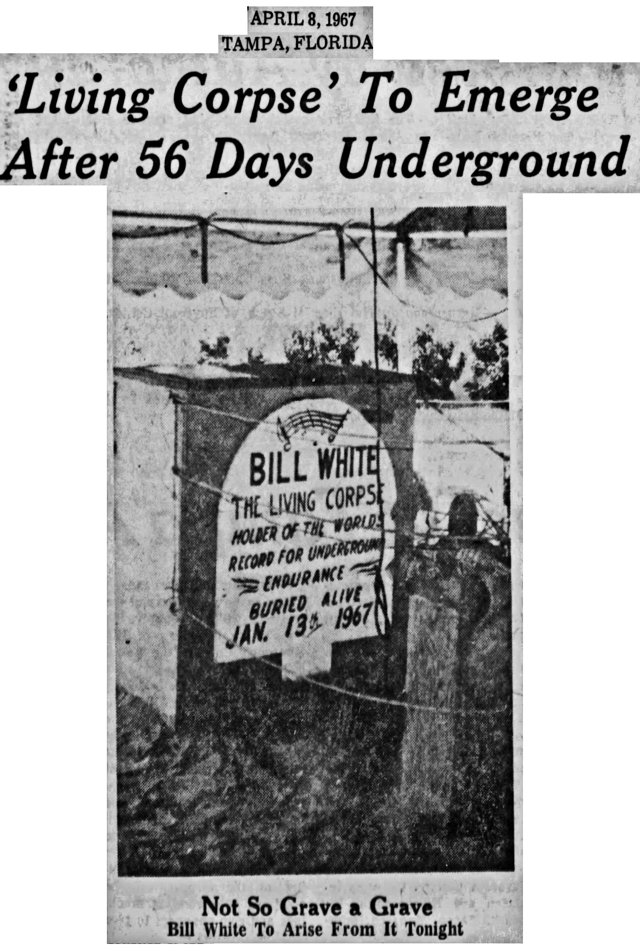

In Largo, Florida in 1967 Bill broke his own record, staying down fifty-six days. Wife Lottie lived in a trailer parked nearby and kept him supplied with food via his airshaft.

In Largo, Florida in 1967 Bill broke his own record, staying down fifty-six days. Wife Lottie lived in a trailer parked nearby and kept him supplied with food via his airshaft.

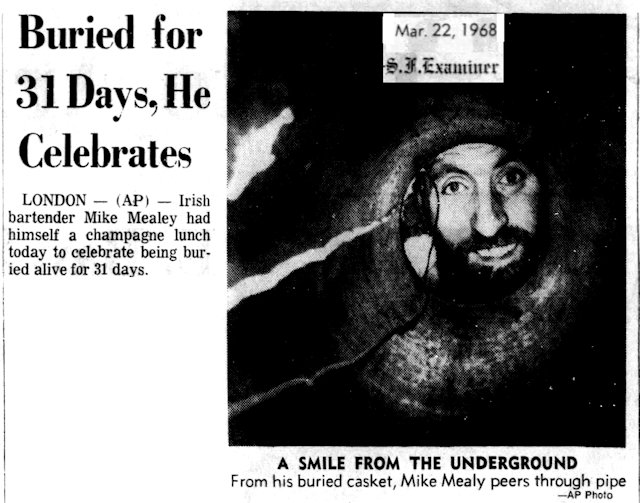

In 1968 America’s “Living Corpse” got some international competition. In London bartender Mike Mealey went eight feet under in an attempt to break White’s record of fifty-six days.

In 1968 America’s “Living Corpse” got some international competition. In London bartender Mike Mealey went eight feet under in an attempt to break White’s record of fifty-six days.

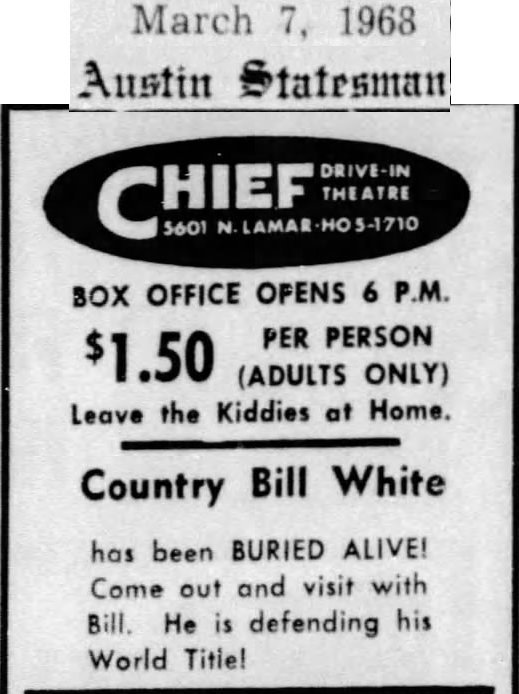

Meanwhile, White was buried at a drive-in-theater in Austin. He vowed to outlast Mealey.

Meanwhile, White was buried at a drive-in-theater in Austin. He vowed to outlast Mealey.

Dueling cadavers.

Note that White was now billing himself as “Country Bill.” Man cannot live by death alone. Between burials Bill White was a country music performer. For White, art imitated death as he combined his two vocations, writing and recording such songs as “Ain’t It Weird?” and “This Is My Box—Go Build Your Own” and, of course, “The Living Corpse” (see link below).

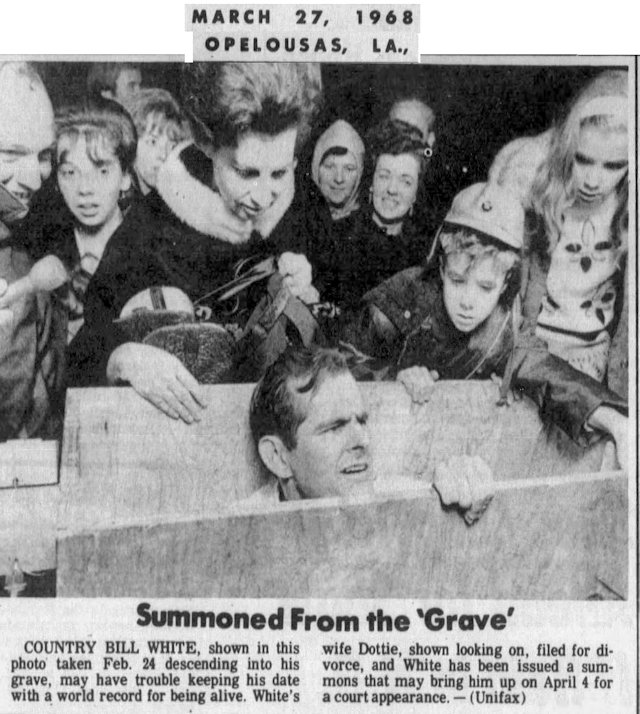

While White was buried in Austin, on March 26, 1968 a Travis County deputy sheriff shoved something besides food down White’s airshaft: a summons ordering White to appear in district court on April 4 for a divorce hearing.

While White was buried in Austin, on March 26, 1968 a Travis County deputy sheriff shoved something besides food down White’s airshaft: a summons ordering White to appear in district court on April 4 for a divorce hearing.

Yes, wife Lottie was suing White for divorce, accusing him of “acts of cruelty.”

The court granted White a delay, and he stayed down sixty-three days and broke his own record.

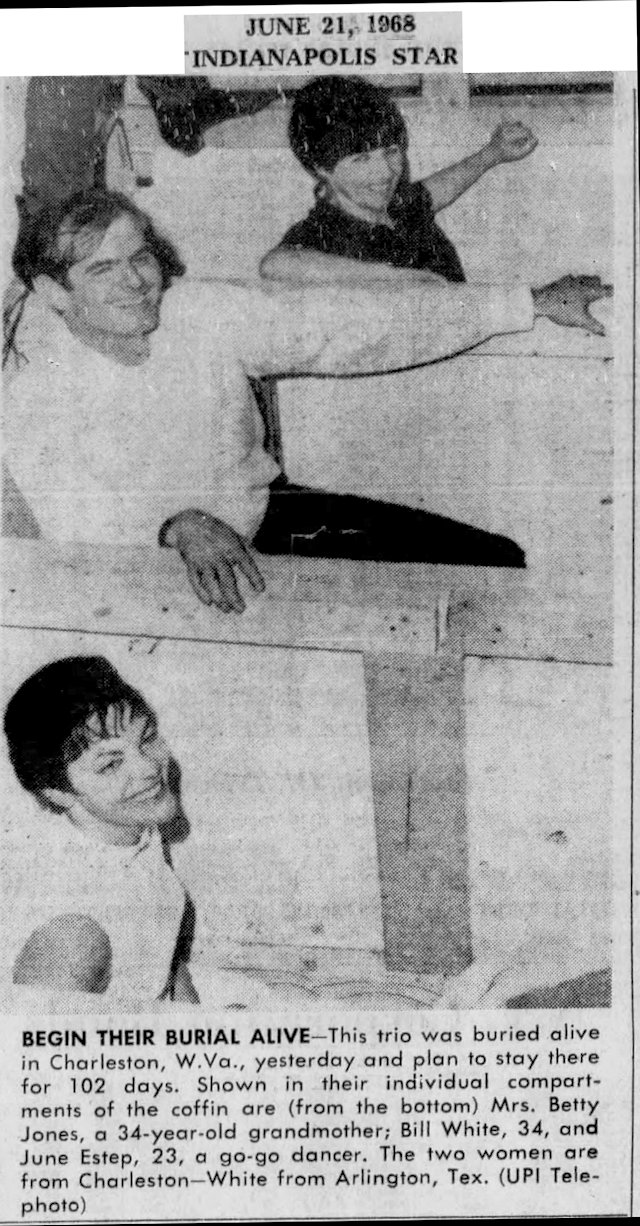

Fast-forward to June 1968 and Charleston, West Virginia. Suddenly single again, Bill took a woman into his grave with him. In fact, two women! But this was not some subterranean swingin’ sixties menage. Buried in the same grave but separate coffins were White, a go-go dancer, and a grandmother. The two women were Charleston residents and no doubt were buried to add a local angle to the publicity stunt.

Fast-forward to June 1968 and Charleston, West Virginia. Suddenly single again, Bill took a woman into his grave with him. In fact, two women! But this was not some subterranean swingin’ sixties menage. Buried in the same grave but separate coffins were White, a go-go dancer, and a grandmother. The two women were Charleston residents and no doubt were buried to add a local angle to the publicity stunt.

By February 1969 Bill had remarried and was living in Arlington. He had met his new wife, Dianne, just as he had met his ex-wife Lottie: Dianne had telephoned him while he was buried.

On February 17 Bill was buried at a strip club in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Topless women danced on his grave.

“This sure beats being buried in a used car lot,” Bill said.

His wife had no comment.

Fast-forward eight years. On January 7, 1977 Bill White married for the sixth time. He again had met his wife-to-be via the telephone, but this time Bill was above ground.

Bride Kay recalled: “The way we met was Bill called a wrong number and got me by accident and—you know Bill—he started talking anyway, tellin’ jokes and all. That night he brought over some flowers and wine and told me he was a living corpse. I didn’t believe it, but then he showed me his scrapbook. I tell you, he throwed me for a loop . . .”

Kay admitted that her husband’s line of work was not conducive to marital togetherness, but she conceded: “At least I know where he is.”

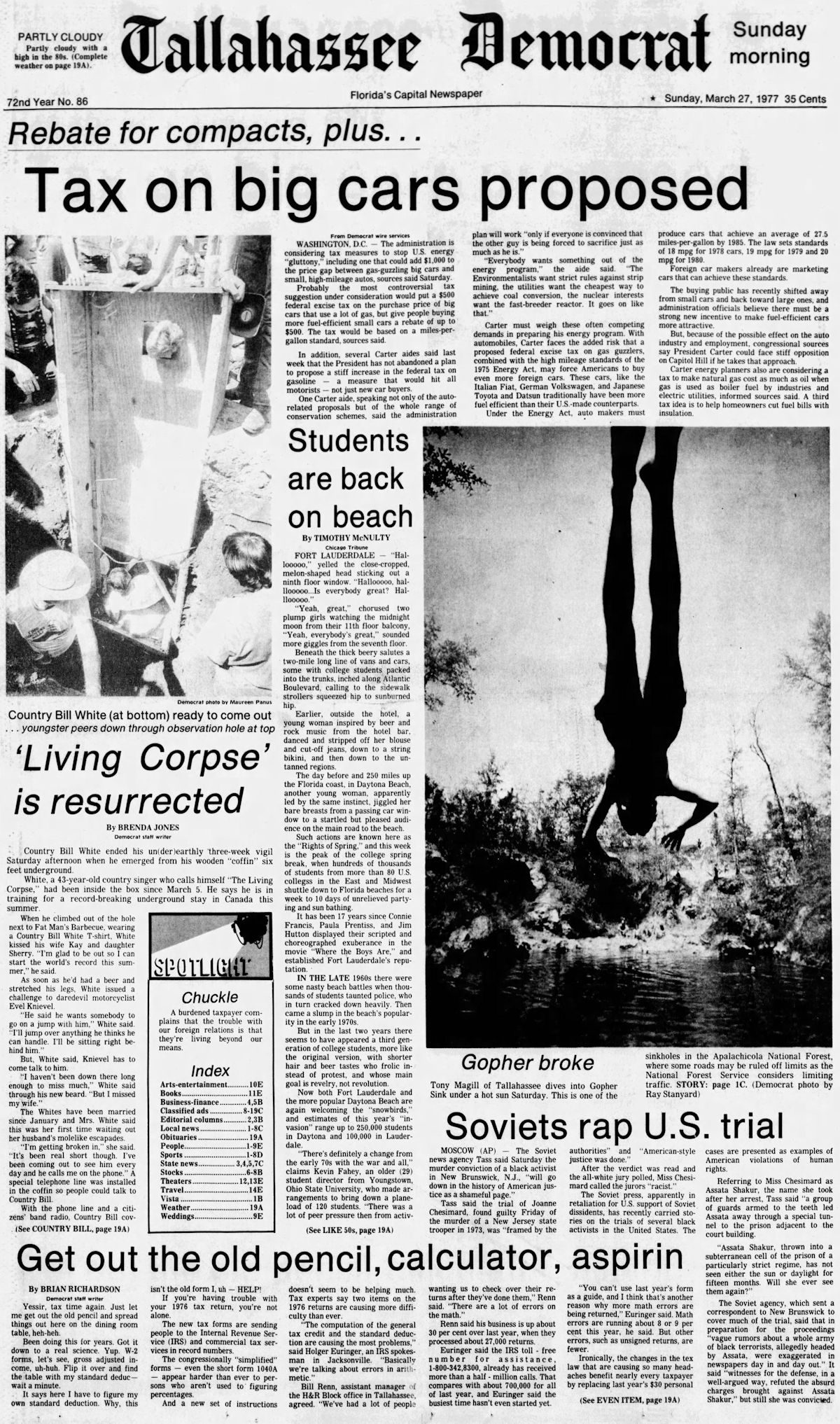

And come March 5, 1977 she knew where he was: buried ’neath the sod at Fat Man’s Bar-B-Que in Tallahassee, Florida.

And come March 5, 1977 she knew where he was: buried ’neath the sod at Fat Man’s Bar-B-Que in Tallahassee, Florida.

This time there was another twist: Before Bill was lowered into the ground, the county sheriff handcuffed him.

This was Bill’s forty-ninth burial. But this burial was not a run for another record. This time Bill planned to stay down for only twenty-three days.

Just to stay in shape.

See, by 1977 the world record for endurance burial was 101 days, set by a Belgian.

Bill White was in training to retake the crown as King Cadaver.

In May 1977 Bill White set out to break the Belgian’s record of 101 days. White was buried in the lot of a mobile home dealership in Dover, Delaware.

This burial was a golden milestone of sorts for White: his fiftieth burial. And he did it in style.

He was laid to rest in a custom, all-electric coffin built by a mobile home manufacturer. It had color TV, three telephones, CB and AM/FM radio, heater, air-conditioner.

And it measured eight by four feet.

“I could raise a family in that size box,” Bill said.

But, alas, as some of Bill’s fans were standing on his grave looking down the airshaft at him, the coffin lid began to cave in from their weight.

But, alas, as some of Bill’s fans were standing on his grave looking down the airshaft at him, the coffin lid began to cave in from their weight.

White again had to be prematurely exhumed.

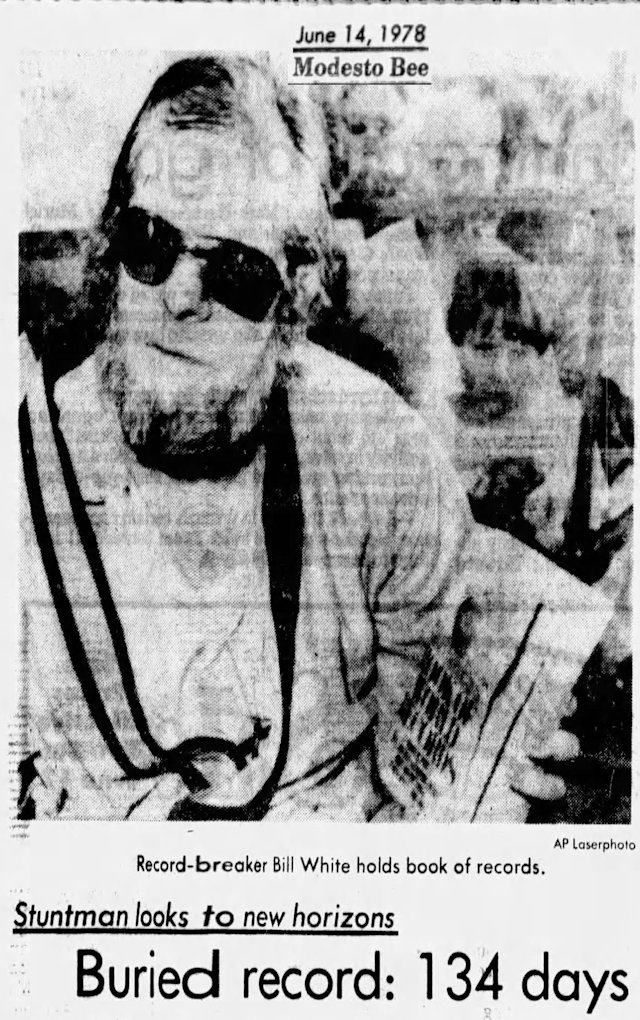

Ever say die: another year, another burial, another world record: On January 9, 1978 White was buried in New Bedford, Massachusetts. This, his fifty-first burial, was sponsored by a local radio station.

As usual, fans could telephone White in his coffin. Or, for fifty cents, they could stand on his grave and look down his airshaft.

No cave-ins this time, and White set a new record of 134 days.

No cave-ins this time, and White set a new record of 134 days.

In 1981 White again broke his own record, staying underground for 140 days (July 31 to December 19) at National Hall country-western nightclub in Killeen.

In 1981 White again broke his own record, staying underground for 140 days (July 31 to December 19) at National Hall country-western nightclub in Killeen.

White said he undertook the Killeen burial after someone had bet him that he was, at age forty-seven, “too old to do a world record again.”

Hold my shroud.

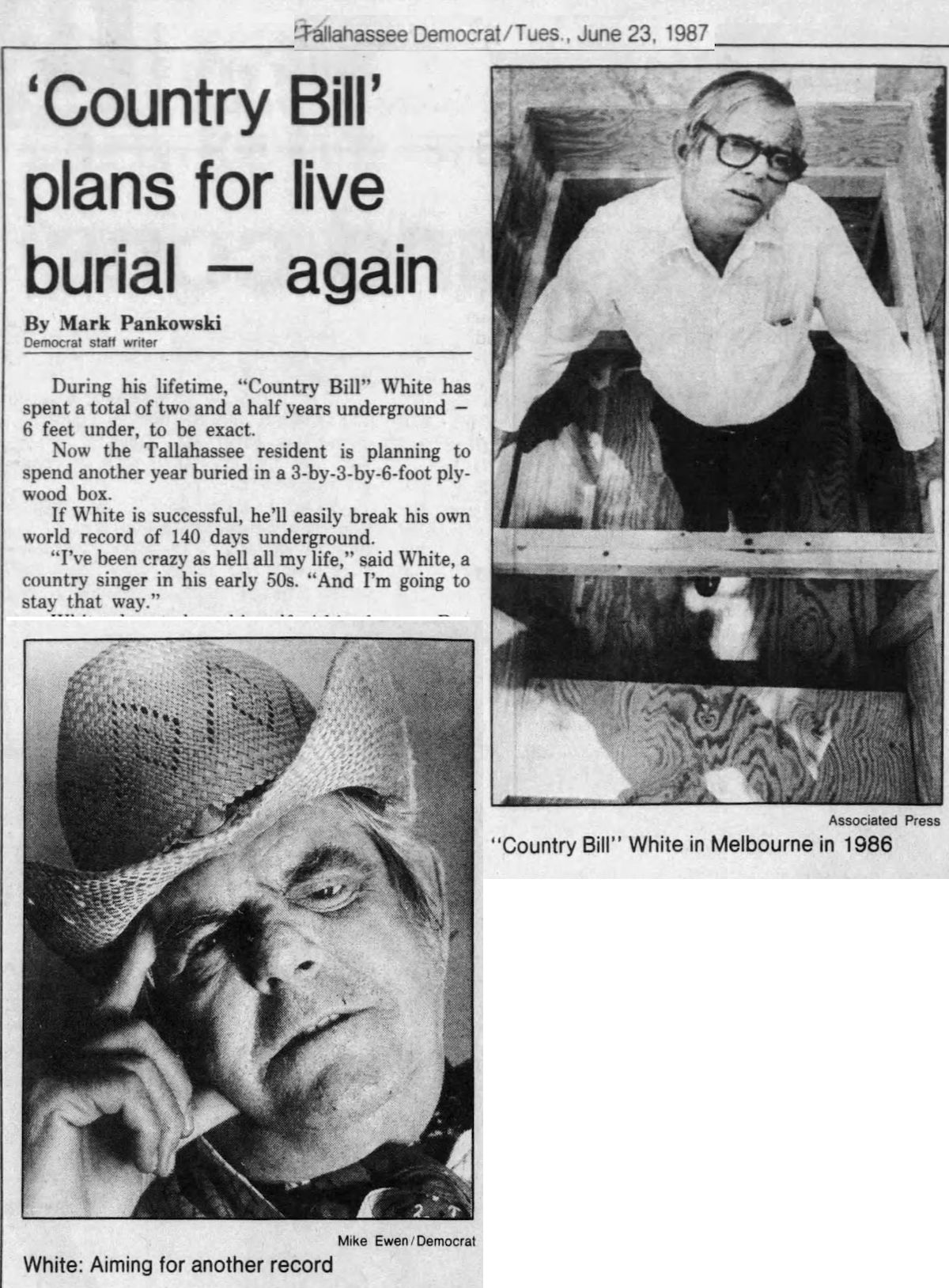

In 1987 Bill White’s record of 140 hours, set in 1981, still stood.

In 1987 Bill White’s record of 140 hours, set in 1981, still stood.

Nonetheless, Bill was talking about trying to break his own record. But his next burial, he vowed, would be his last.

But as far as I can determine, the Living Corpse did not attempt another burial.

By 1987 Bill White was fifty-three years old. He had been buried sixty-one times. He had spent two and a half years of the last twenty-three underground in a box with nightcrawlers for neighbors.

Perhaps just as a gunfighter knows when to hang up the holster, just as a matador knows when to hang up the cape, a living corpse knows when to hang up the shroud.

Bill White’s records were listed in the Guinness Book of World Records until the book stopped awarding a record for “endurance burial” because Guinness deemed the stunt to be dangerous.

On December 21, 2006 “Country Bill” White died. He was buried in his home county in the Florida Panhandle.

On December 21, 2006 “Country Bill” White died. He was buried in his home county in the Florida Panhandle.

“The Living Corpse” has now been buried for fifteen years, ten months, and nine days.

That’s a new record for him.

Hear Bill White’s 1969 recording of “The Living Corpse” on YouTube.