When the “Open” sign was hung on the front of Joseph K. Turner’s grocery store for the first time, the population of Fort Worth was about 6,000. R. E. Beckham was mayor. Rutherford B. Hayes was president. In major league baseball Paul Hines of the Providence Grays won the home run title with four.

A horse and buggy cost about $125. A vacant lot on the near South Side, $75-$800.

In Turner’s store, bacon was 12 1/2 cents a pound; ham, 11 cents a pound; sugar, 11 cents a pound; coffee, 25 cents a pound.

When the “Closed” sign was hung on the front of Lloyd Hallaran’s grocery store for the last time, Fort Worth’s population was about 400,000. Bob Bolen was mayor. Ronald Reagan was president. In major league baseball Jesse Barfield of the Toronto Blue Jays won the home run title with forty.

A new Ford Mustang cost about $7,000. A vacant lot on the near South Side, $5,000-$20,000.

In Hallaran’s store, bacon was $2.99 a pound; ham, $3.99 a pound; sugar, 35 cents a pound; coffee, $1.99 a pound.

In between Turner’s opening and Hallaran’s closing were twenty presidents, two world wars, thirty-seven mayors, four major floods, 108 years of a Fort Worth institution.

And uncounted cans of rattlesnake meat.

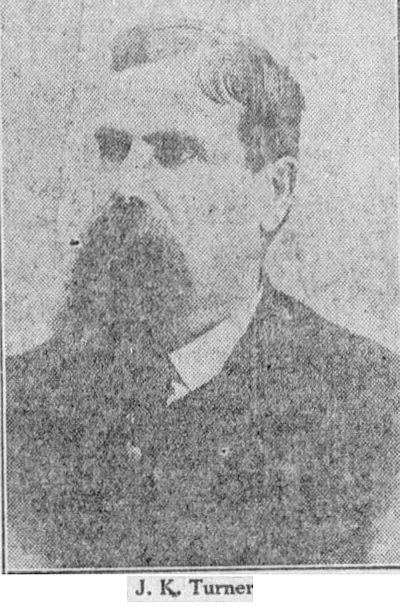

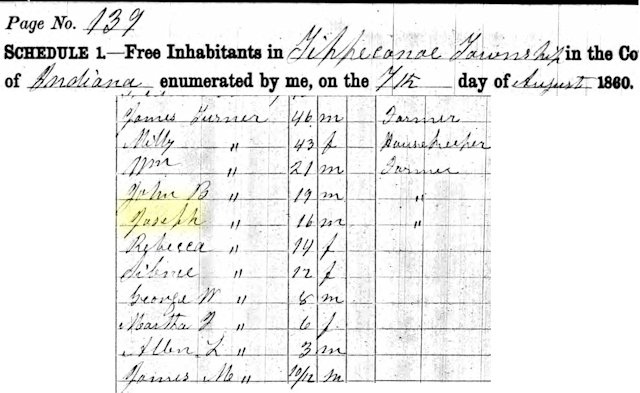

Joseph K. Turner was born in Indiana in 1844. He enlisted in the Union army at age eighteen, fought in the battles of Chickamauga and Mission Ridge.

By 1877 he was in Fort Worth, one of the hundreds—and eventually thousands—of people who moved to Fort Worth during the boom triggered by arrival of the Texas & Pacific railroad in 1876. After the railroad arrived, Fort Worth suddenly needed more everything, including grocery stores.

Turner’s early experience here shows how the boom built Fort Worth:

When Joseph H. Brown had opened a grocery store here in 1872, Fort Worth had fewer than a dozen grocers. After the railroad arrived, and the boom began, one of Brown’s employees, S. P. Tucker, left Brown to open his own store.

Soon after, two of Tucker’s employees left him to open their own store.

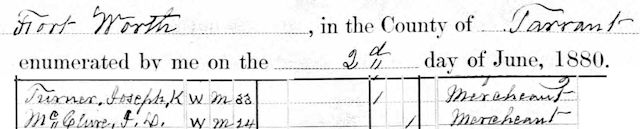

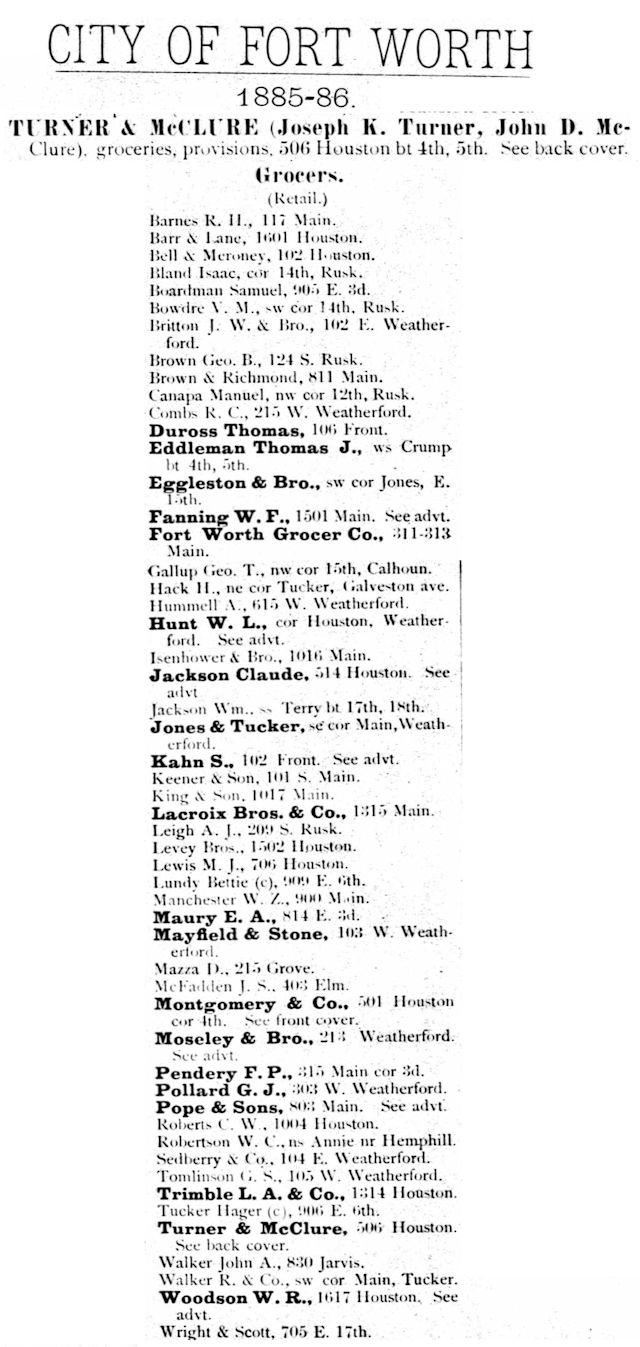

Those two employees were Joseph K. Turner and John D. McClure. In 1878 they opened a grocery store on Houston Street between 6th and 7th streets.

With the railroad, ice-cooled rail cars brought Turner & McClure and other grocers perishable foods—from oysters to ice cream, from asparagus to zucchini—that preboom grocers could only have dreamed of.

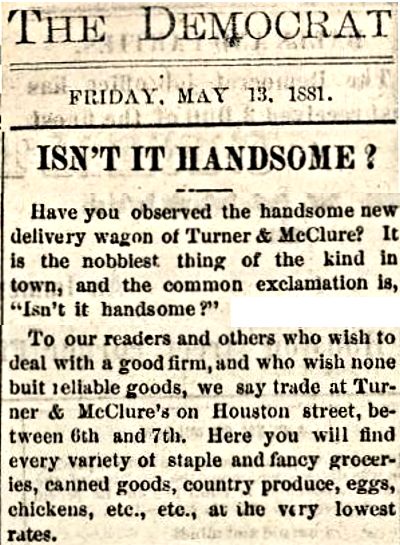

When Turner and McClure opened their store, Fort Worth was compact enough that Turner and McClure made deliveries using wheelbarrows and handcarts. But soon the town had grown enough that Turner and McClure bought a horse and wagon for deliveries. The new ride was, the Daily Democrat decreed, “the nobbiest thing of its kind.”

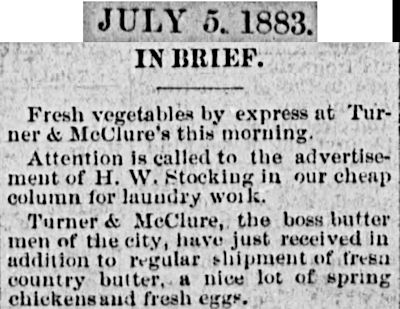

And in 1883 the Daily Democrat proclaimed Turner and McClure to be the “boss butter men of the city.”

By 1885 Turner & McClure had moved two blocks north on Houston Street. Fort Worth continued to boom, now with four railroads. And fifty-four grocery stores.

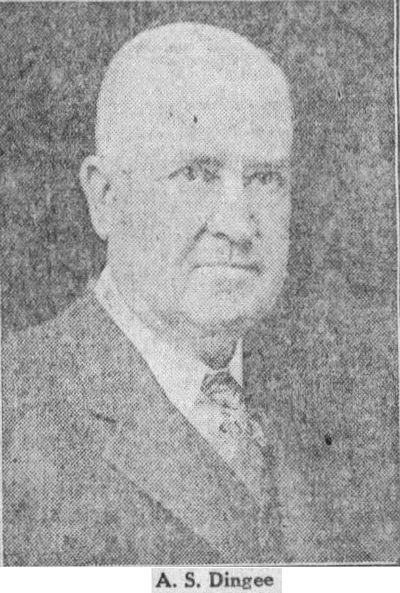

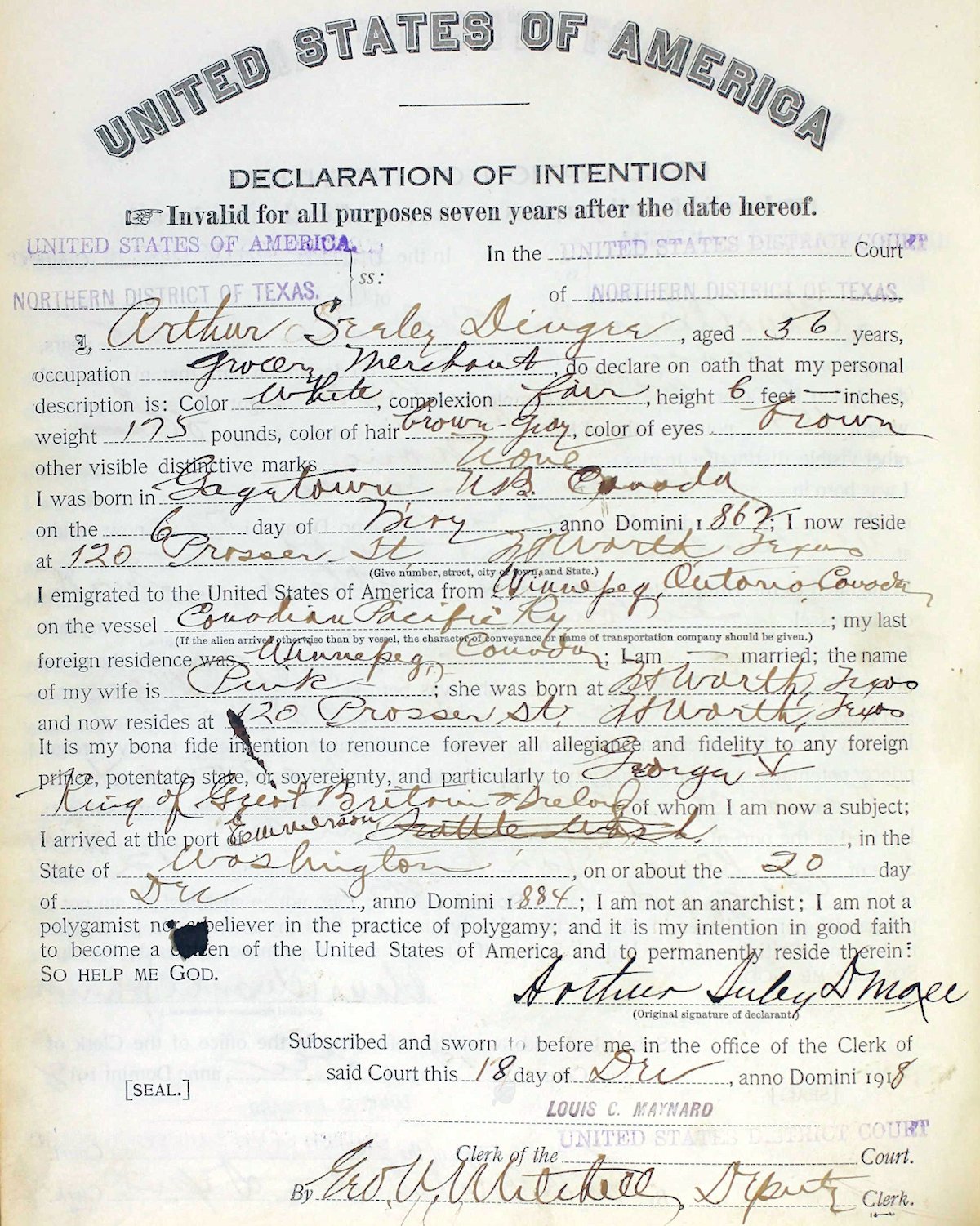

Arthur Seeley Dingee was born in Canada in 1862. As a young man he had worked as a land surveyor in the vastness of Canada’s Northwest Territories. He immigrated to America in 1884, by 1886 was in Fort Worth, where he traded the chain and tape for the cash register and scales.

In 1886 Turner and McClure needed an extra hand in their store. Turner offered Dingee a generous $50 ($1,600 today) a month on the condition that Dingee would promise to be a permanent employee.

Arthur Seeley Dingee promised.

And, boy, did he keep his promise!

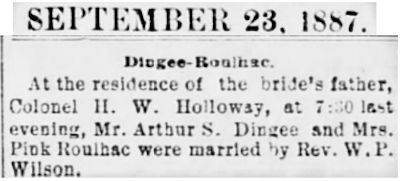

In 1887 Dingee married Pink Roulhac, daughter of Confederate Colonel Henry Clay Holloway. The Holloways were among Fort Worth’s first families. Pink had been born in 1862 on the Holloway homestead in the Samuels Avenue “peninsula.” On that land in 1849 Major Ripley Arnold and his soldiers had camped before moving up onto the bluff to build a fort. On the Holloway land also were located Traders Oak and a cold spring. Newlyweds Arthur and Pink lived on her father’s homestead (see below).

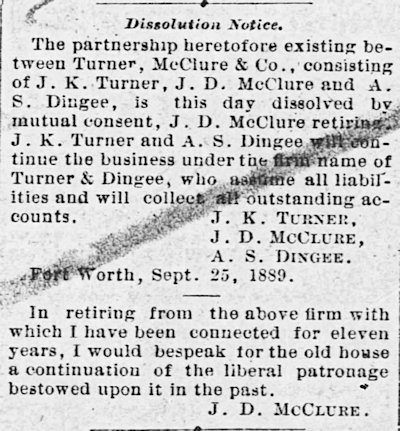

By 1889 Arthur Dingee had become a third partner in Turner & McClure. Later that year, with the financial aid of Colonel Holloway, Dingee bought John D. McClure’s interest in Turner & McClure, creating Turner & Dingee.

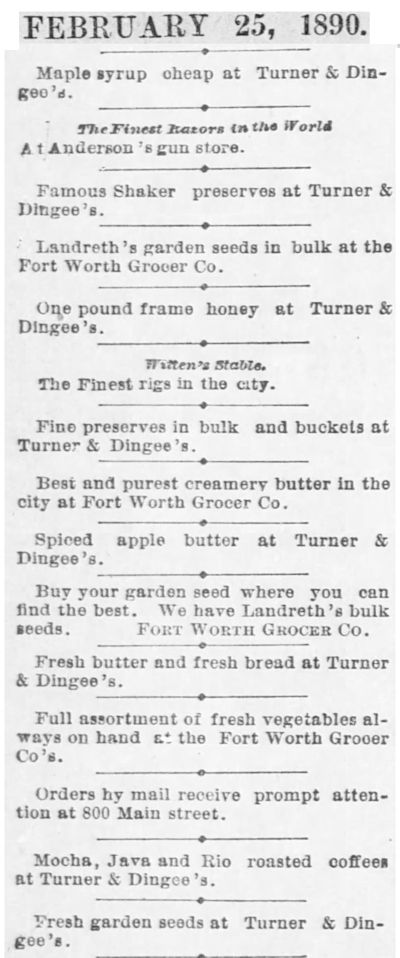

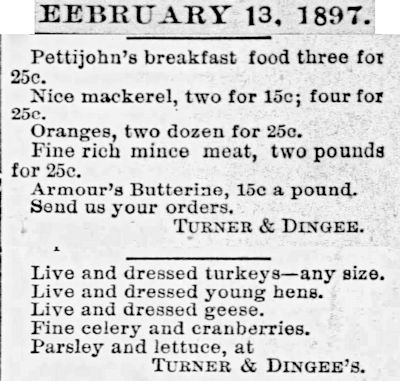

These one-line Turner & Dingee ads are from 1890.

The store bought fresh produce and live fowl from farmers who lined their wagons up at the open-air market along 4th Street.

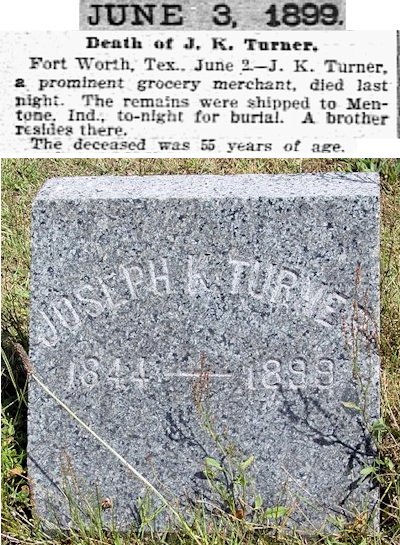

Joseph K. Turner died June 1, 1899 at age fifty-five, leaving Arthur Dingee as the sole owner of the company. According to one story, Dingee was so grateful to Turner for that generous salary given in 1886 that Dingee retained the name of his late partner in the store’s name.

(Of course, Dingee also no doubt appreciated the fact that “Turner & Dingee” after ten years had a lot of name recognition.)

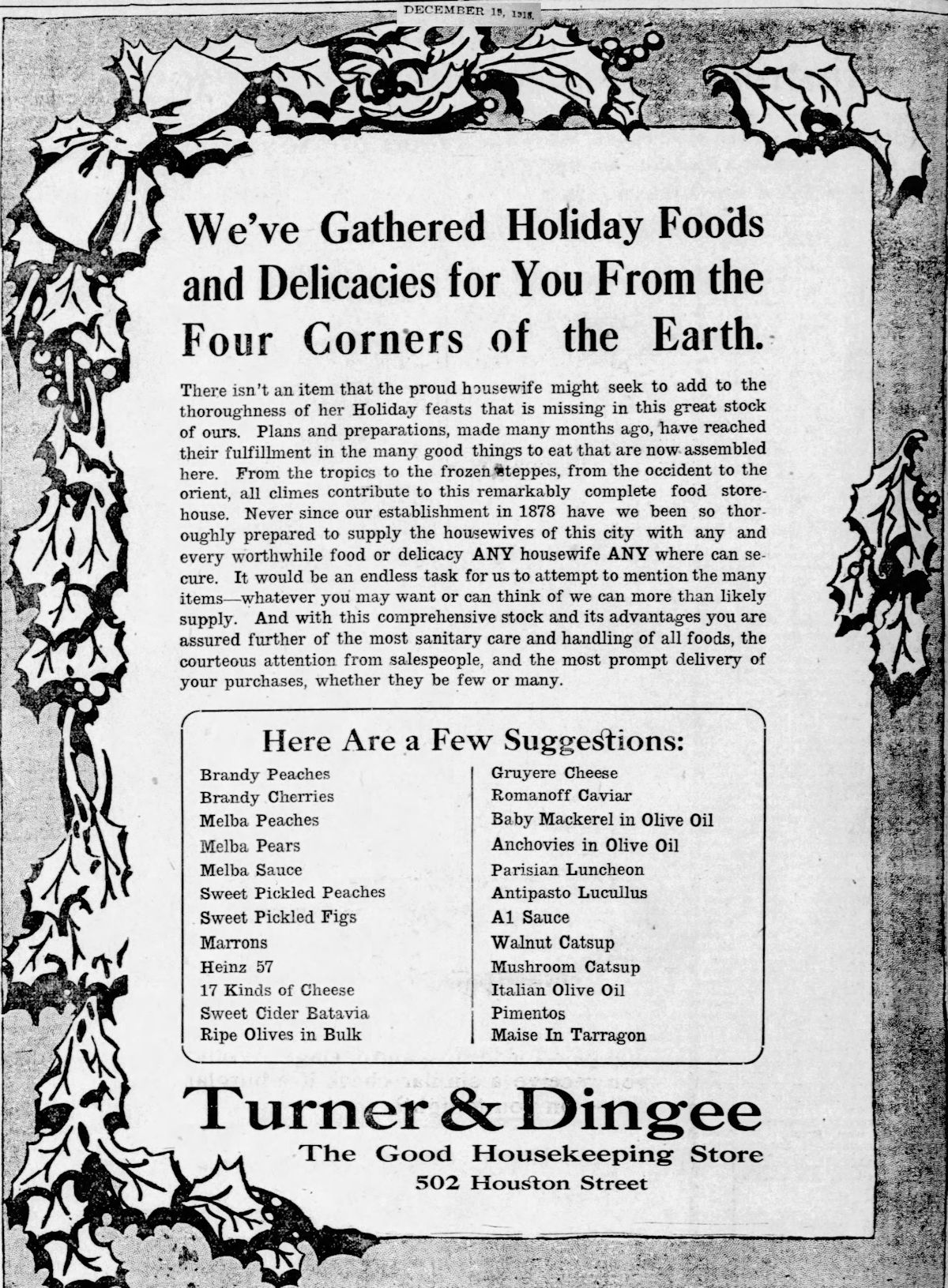

At Christmas 1915 Dingee stressed “prompt delivery” and “sanitary care and handling of all foods” and offered enough cheeses to outfit a Monty Python skit.

“From the tropics to the frozen Steppes, from the occident to the orient, all climes contribute to this remarkably complete food storehouse.”

In addition to sweet cider and brandied fruits, there was eye candy at Turner & Dingee in those early days: A streetcar track ran down Houston Street past the store. At the clang of each streetcar bell, men in the store, with Pavlovian predictability, would hurry to the front window of the store to watch women hike the hem of their skirt above their ankles as the women boarded the car.

Mercy!

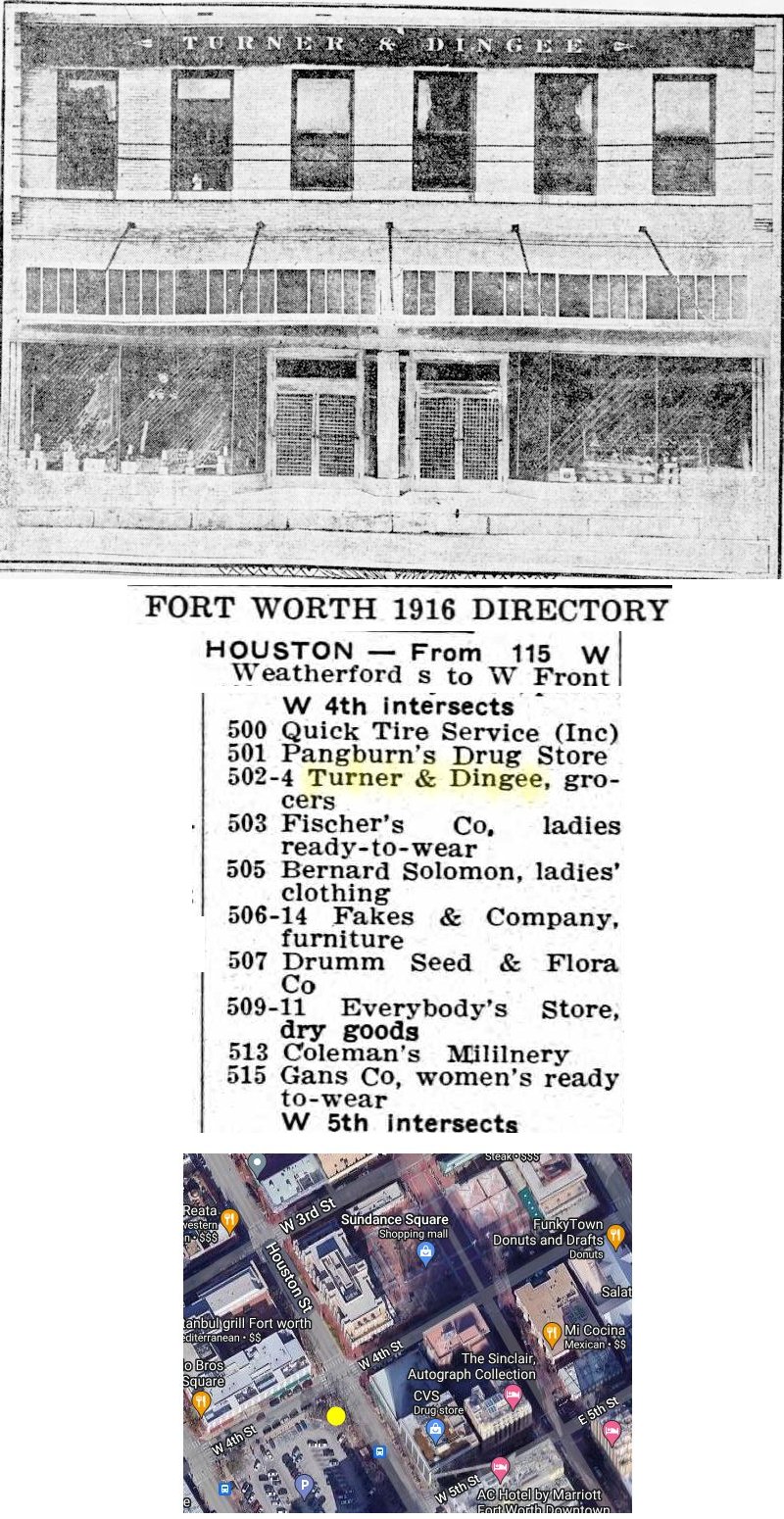

In 1916 Turner & Dingee was located between a tire service company and a Fakes in one of that department store’s several downtown incarnations.

By 1916 the wheelbarrow and handcart of the early days of the store’s grocery delivery had been replaced by twelve wagons and three automobiles.

(Everybody’s Store was a women’s store, not the Everybody’s department store of the Leonard brothers.)

About 1917 Arthur Dingee made three business decisions, the seemingly least significant of which would have lasting impact on the history of his store.

- Dingee hired Lloyd Francis Hallaran. Hallaran, nineteen, had built a small business raising pigeons and selling squab to, among others, residents of Quality Hill, the Metropolitan Hotel, Joseph’s Café, and Turner & Dingee.

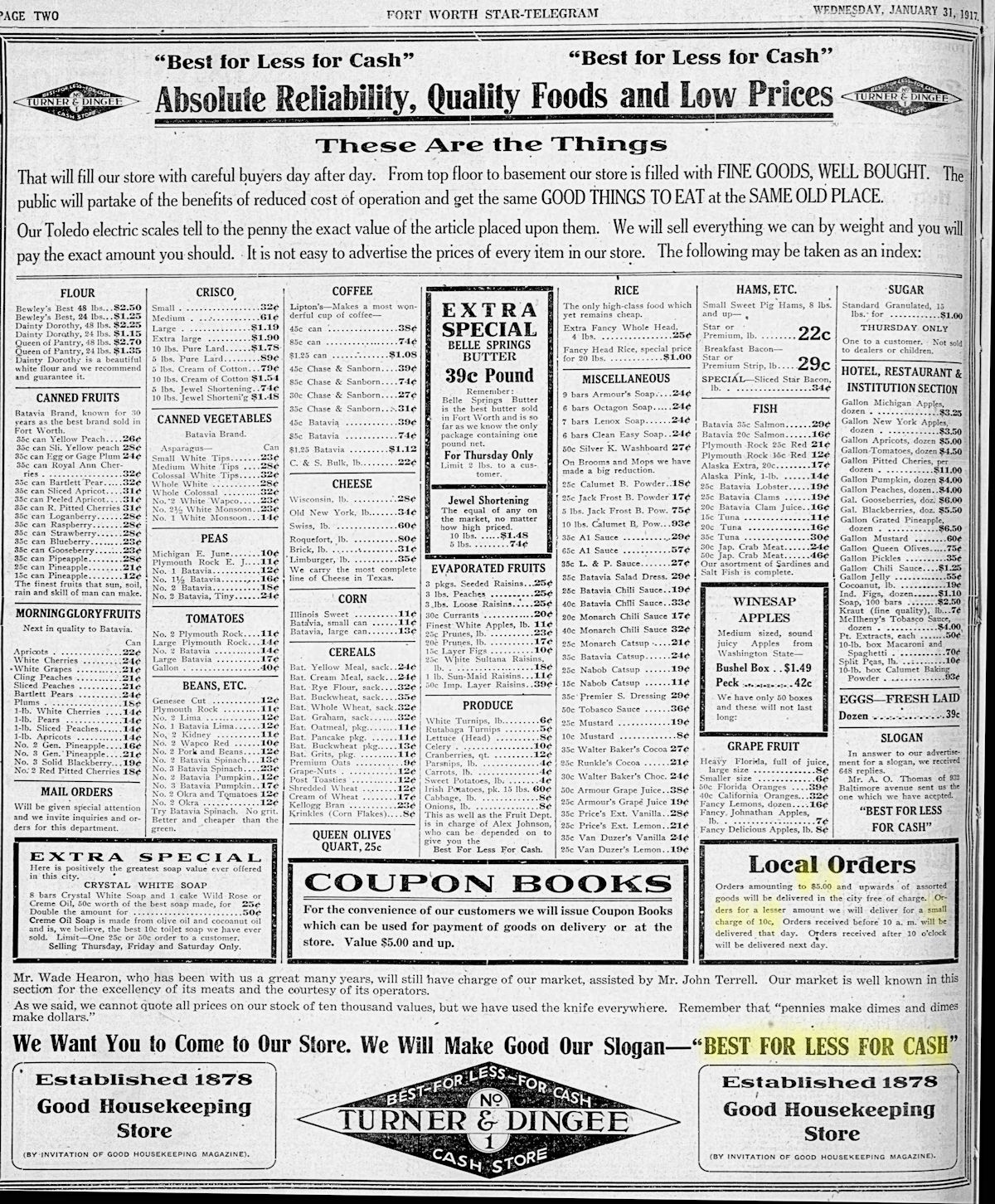

- Dingee adapted a policy of “cash-and-carry” for his store. Turner & Dingee had long offered credit and free home delivery. Now the store restricted credit, expected customers to pay cash for their purchases in the store and carry those purchases back home themselves. The store began to offer a discount for cash. The store’s new slogan was “Best for Less for Cash.”

Further, now only orders of at least $5 ($110 today) would be delivered free. The store would levy a “small charge of 10c” ($2 today) for lesser orders. Expecting a sharp decrease in home deliveries, Dingee sacked most of his delivery boys.

The job of delivery boy might seem menial to us now, but delivery boys were important a century ago. They were the Fedex/Amazon/Instacart drivers of their day. Delivery boys were a liaison between store and customer, the “face” of a store in the neighborhoods it served.

A delivery boy might service more than two hundred customers and make his rounds three times a day.

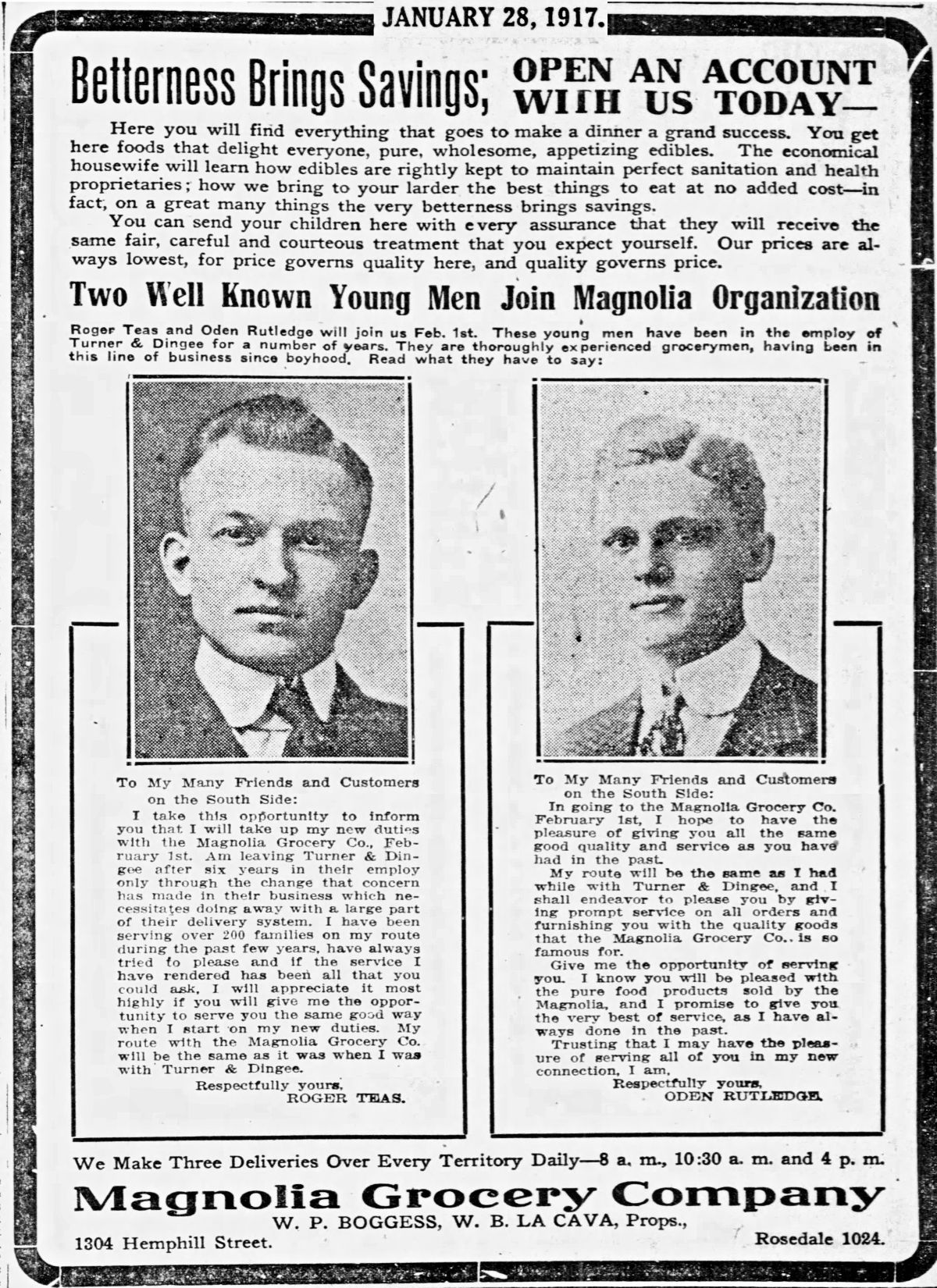

After Arthur Dingee sacked most of his delivery boys, competing grocer William La Cava hired two of them and crowed about his coup in his newspaper ad.

La Cava, a prominent businessman on the near South Side, owned Magnolia Grocery at 1304 Hemphill Street.

La Cava’s ad seemed even to mock Dingee’s new “Best for Less for Cash” slogan with another slogan: “Betterness Brings Savings.”

La Cava’s ad announced that his two new delivery boys would drive the same routes for La Cava that they had driven for Dingee.

Dingee’s attempt to restrict home delivery had unexpected results: The store received so many orders for more than $5 that Dingee had to close the store for a day to catch up on orders and had to rent a flatbed truck to deliver the orders because he had sacked all his delivery boys.

Chastened, Dingee hired more delivery boys and returned his store to its policy of free delivery regardless of the amount of purchase.

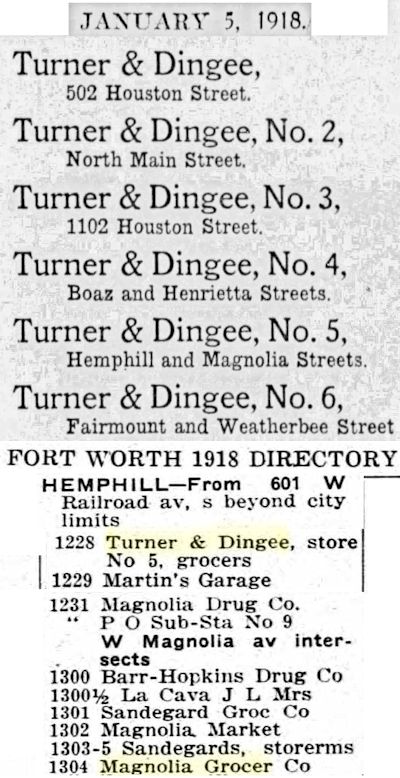

- Dingee began to open branch stores. By 1918 he had six branch stores, including one on William La Cava’s own turf: Turner & Dingee store no. 5 opened just across Magnolia Street from La Cava’s Magnolia Grocery.

Meanwhile, in 1918 Arthur Seeley Dingee, vowing to “renounce forever all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty, and particularly to George V, King of Great Britain and Ireland,” applied for U.S. citizenship.

The year 1921 brought another footnote to the history of the Holloway/Dingee property on Samuels Avenue. Fort Worth’s Hangman’s Tree, used for at least two lynchings, was located on the Holloway/Dingee property. Arthur and Pink Dingee lived on Prosser Street; the tree was three blocks north on Northeast 12th Street (just a mile by car from the Ku Klux Klan lodge hall on North Main Street). After two lynchings at the tree on December 22, 1920 and December 11, 1921, Mrs. Dingee had Hangman’s Tree cut down.

Meanwhile, Lloyd Hallaran had begun his ascent in the Turner & Dingee hierarchy: By 1922 he was manager of the mother store on Houston Street.

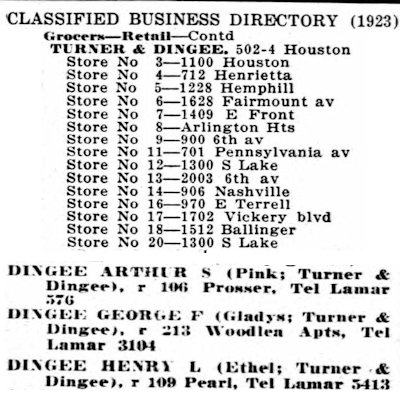

By 1923 there were sixteen Turner & Dingee stores. And Arthur’s two sons had joined the company.

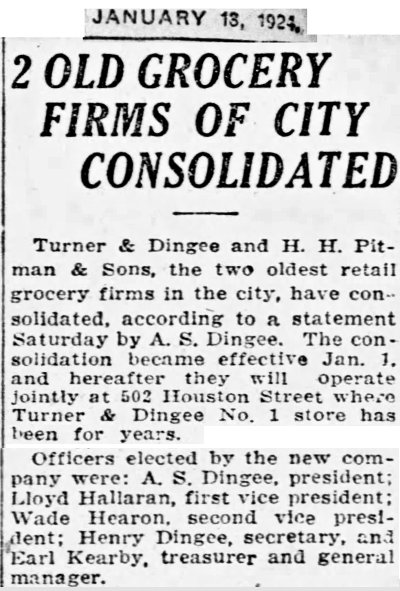

But the next year the city’s oldest grocery business (1878) bought out the city’s second-oldest grocery business (1895). The new company elected officers: Dingee was president; Lloyd Hallaran was first vice president. And the new company sold off all the Turner & Dingee branch stores. Only the mother store on Houston Street remained.

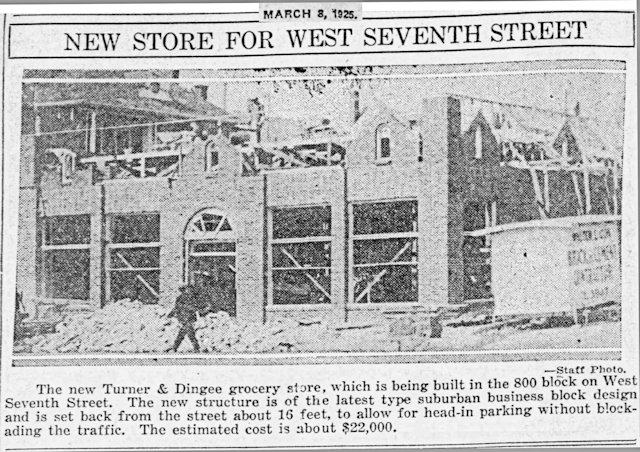

But the next year that, too, changed: Rent on the Houston Street building increased so much that Dingee, Hallaran et al. built a new home at 800 West 7th Street and moved from downtown’s busiest shopping street to the southwest edge of downtown. In 1925 that part of downtown still had many single-family houses. So, Turner & Dingee gained some residential business. But eventually, of course, those houses were pushed out by businesses, putting the West 7th Street store back in the expanding central business district.

In fact, Turner & Dingee became popular with office workers. At lunchtime workers flocked to Turner & Dingee to order a fresh sandwich to eat at the store’s standup counter or to take to a bench in nearby Burnett Park.

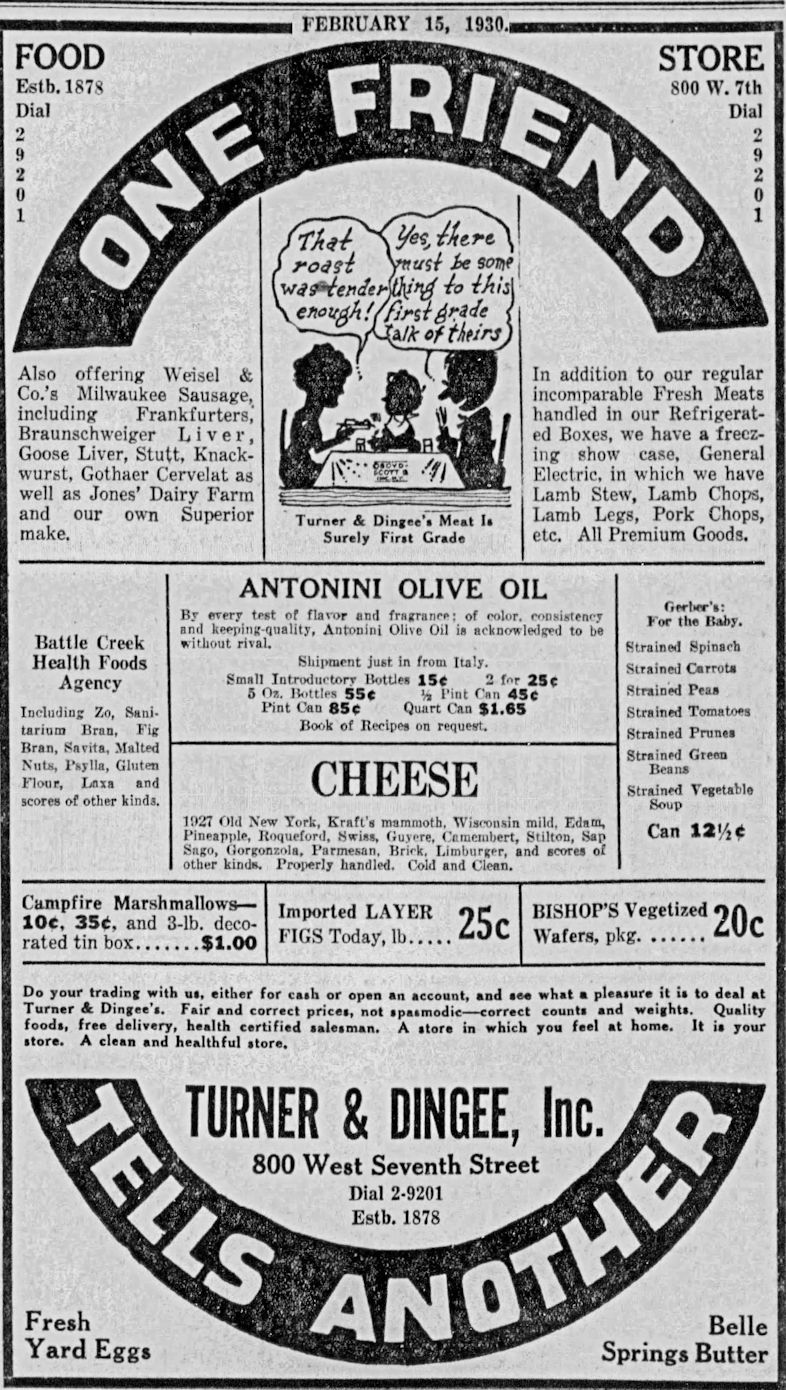

An ad from 1930.

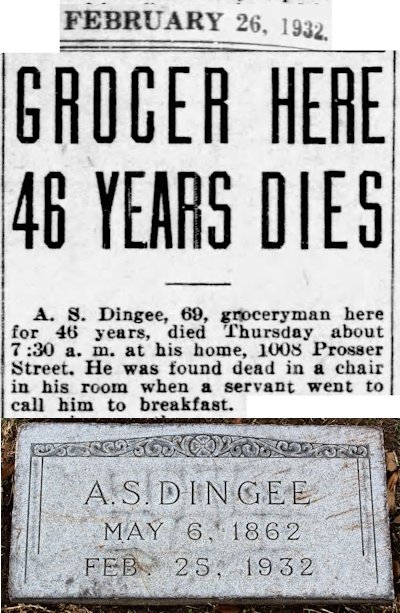

Arthur Seeley Dingee, who had hired on in 1886 with the promise to stay a while, died in 1932 after forty-six years with the company that came to bear his name. Upon Dingee’s death son Henry became president of the company.

Arthur Dingee is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

Soon after the death of Mrs. Dingee in 1939, Lloyd Hallaran became president of the company. There were no Dingees among the company’s officers. These 1941 ads by local businesses congratulated the Interstate theater chain as its Majestic Theater celebrated thirty-five years in Fort Worth.

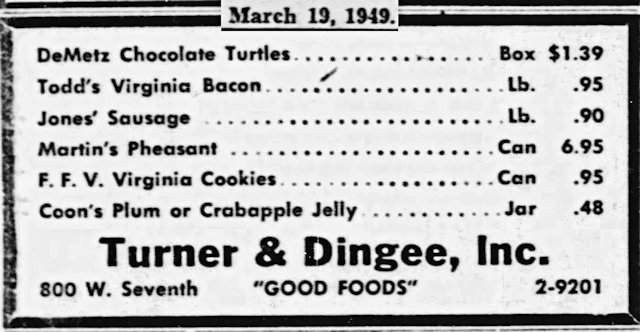

This ad from 1949 is low-key: “Good Foods.”

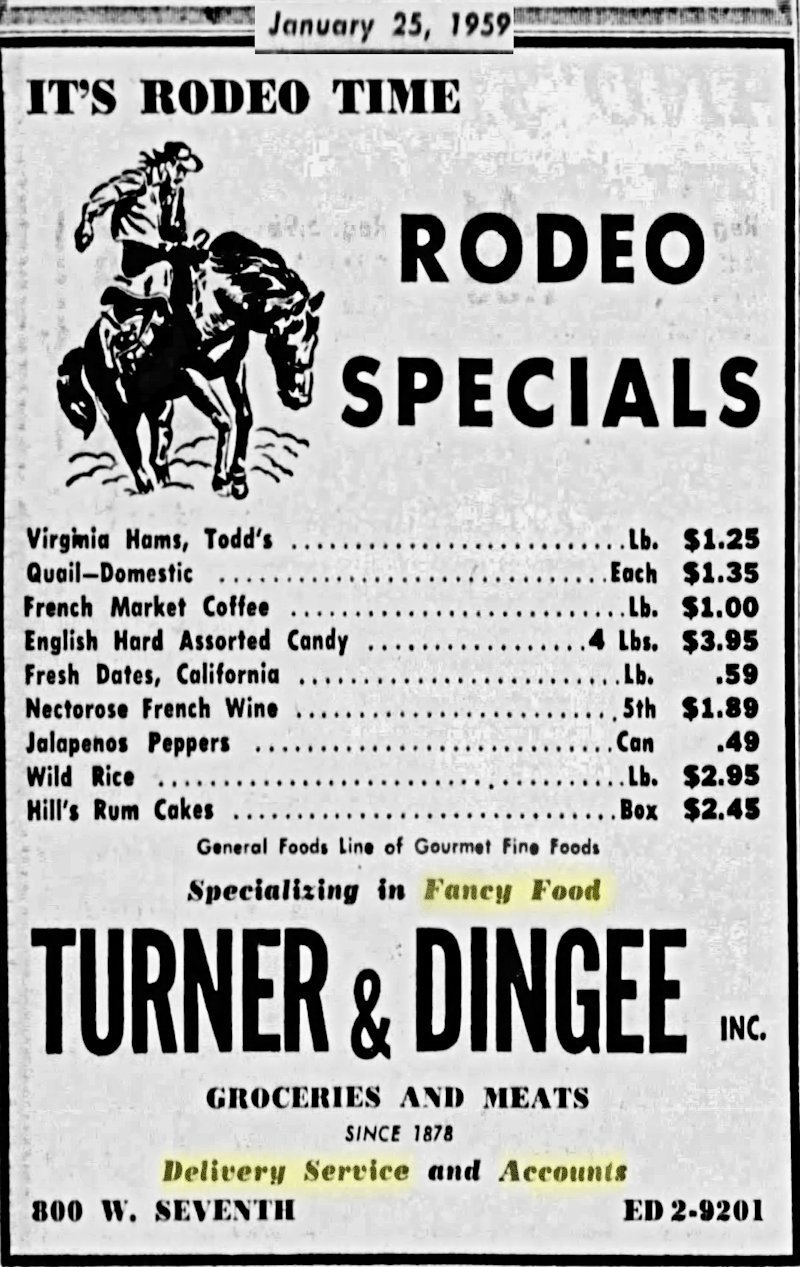

But ten years later this 1959 ad contains the three keystones of Turner & Dingee:

- “Delivery Service”

- “Accounts” (credit)

- “Fancy Food”

Of course, Turner & Dingee stocked national brands and brands made by local businesses: Swift and Armour, Bewley, Mrs Baird’s, King, Waples Platter.

But Turner & Dingee also had developed a reputation for stocking gourmet and hard-to-find foods: chocolate-covered ants, caterpillars, smoked octopus, French truffles, turtle meat, lychees, clam juice, grape leaves.

Hallaran sold jars of Beluga caviar and cans of rattlesnake meat.

And jars of calf’s-foot jelly, which, he explained, invalids and convalescents ate to coagulate their blood.

His store ground its own whole-wheat flour, made its own peanut butter. Customers enjoyed watching the process. No charge.

Hallaran barbecued chickens for Amon Carter when Carter entertained at Shady Oak Ranch.

Turner and Dingee stocked fancy foods, in part, because the store had long catered to the “carriage trade,” even after limousines had replaced carriages. Some affluent residents of Quality Hill, Arlington Heights, and the near South Side had traveled extensively, even abroad, and had been exposed to—and developed a taste for—foods beyond steak ’n’ taters.

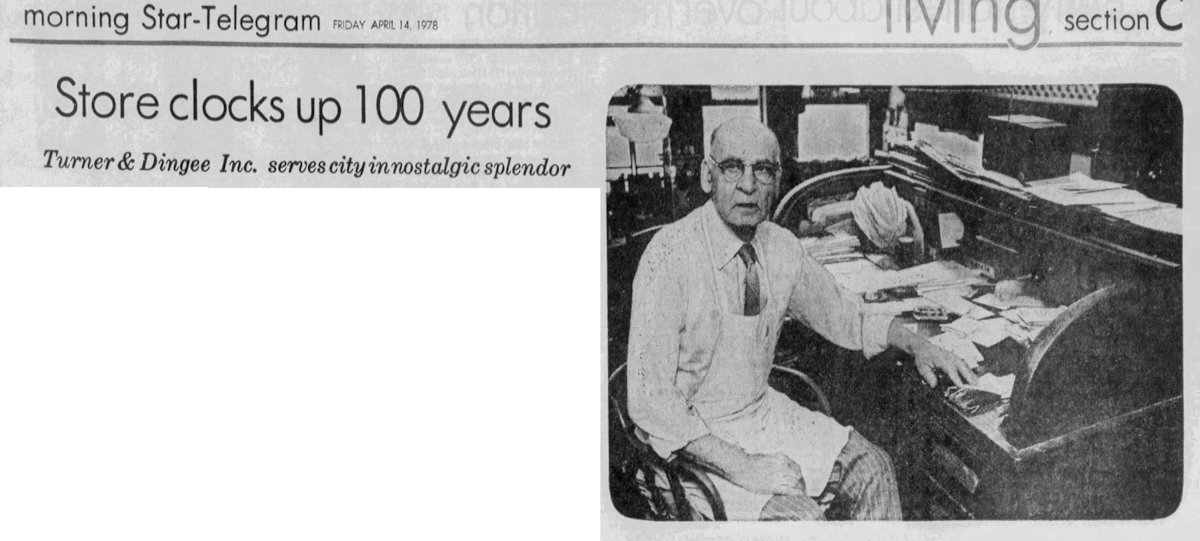

Fast-forward to 1978. Lloyd Hallaran had been with Turner & Dingee sixty-one years. He was eighty years old. Shucks, that’s nothing. In 1978 his store was one hundred years old—a record for a Fort Worth grocery store.

Predictably, by 1978 the world had changed since Lloyd Hallaran had gone to work for Arthur Dingee.

A lot.

For example, by 1978 fewer people lived—and shopped—downtown. Consumers now bought their groceries from chain supermarkets or from the few remaining neighborhood grocery stores.

More change: Over the years the widening of West 7th Street to the south and the expansion of First Methodist Church to the north had nipped away at Turner & Dingee’s parking area.

Also, by its centennial the store was making fewer deliveries to Hallaran’s regular customers on the near South Side, Arlington Heights, and the remnants of Quality Hill, in part, Hallaran said, because “a lot of them are passing away.”

Yes, a lot of change: By 1978 Lloyd Hallaran, after keeping it in stock for discriminating customers for years, could no longer find canned rattlesnake meat.

The store on West 7th Street in 1978—Turner & Dingee’s centennial year. (Photo from Texas Historical Commission.)

At age eighty Lloyd Hallaran was philosophical about age. He joked that he had delivered Turner & Dingee ground round to the Last Supper.

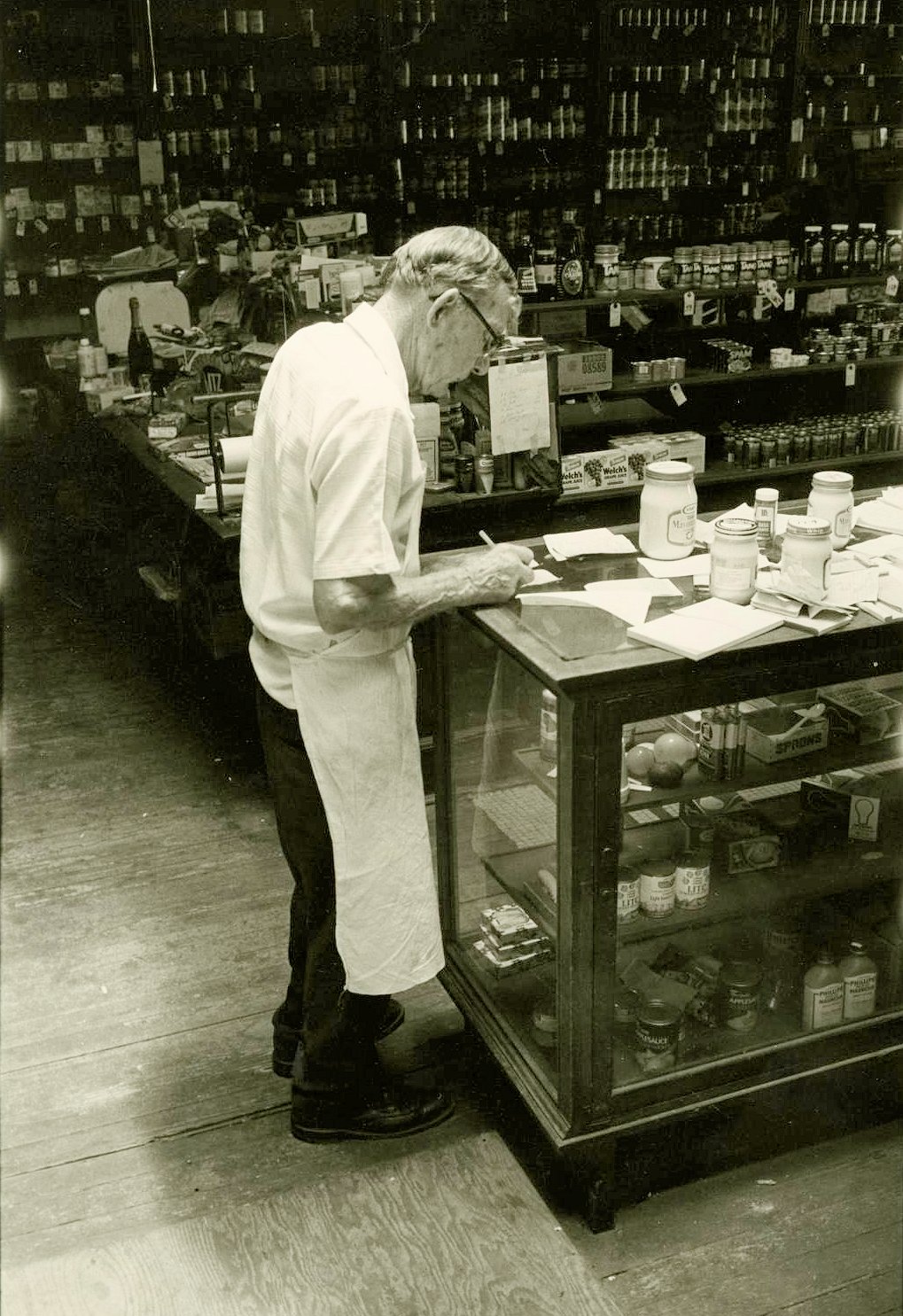

By 1978 the Turner & Dingee name was a throwback to buggies and bustles, the store itself a throwback to flappers and flivvers. To walk through its double wooden screen doors was to walk through a portal to the past: creaky wooden floors, stamped tin ceiling, ceiling fans, display cases of wood and glass, rolltop desk, brass cash register, white Toledo scales that had weighed tons of beef and bratwurst, a basket trolley that carried receipts from the first floor up to Hallaran’s office on the second floor.

There was an Atwater Kent cathedral radio from which customers might half-expect to hear FDR deliver a fireside chat. On one wall hung a Seth Thomas wall clock whose hands, the store’s furnishings strongly suggested, ran backward—back to the 1940s, the 1930s, the 1920s.

All of it presided over by a man born in the nineteenth century. Lloyd Hallaran, like his store, had become an anachronism. But an anachronism, viewed through a different prism, is an institution. Lloyd Hallaran indeed had become a downtown institution, like Monroe Odom or Frankie Brierton or Nick Koutsoubos.

Lloyd Halloran. (Photo from Byrd Williams Family Photography Collection, University of North Texas Special Collections.)

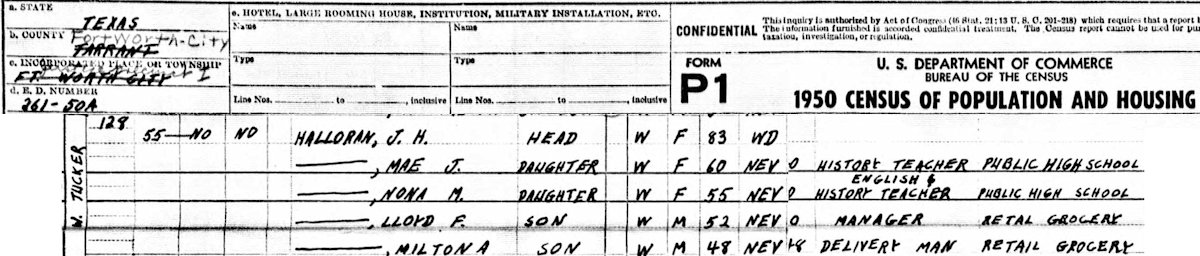

Storekeeper Lloyd Hallaran was assisted by his “baby” brother Milton: Milton was three years younger and had worked at the store since about 1923. By the early 1980s Milton made most of the store’s deliveries. Milton had become perhaps the world’s oldest delivery boy, if a man past eighty can be called a “boy.”

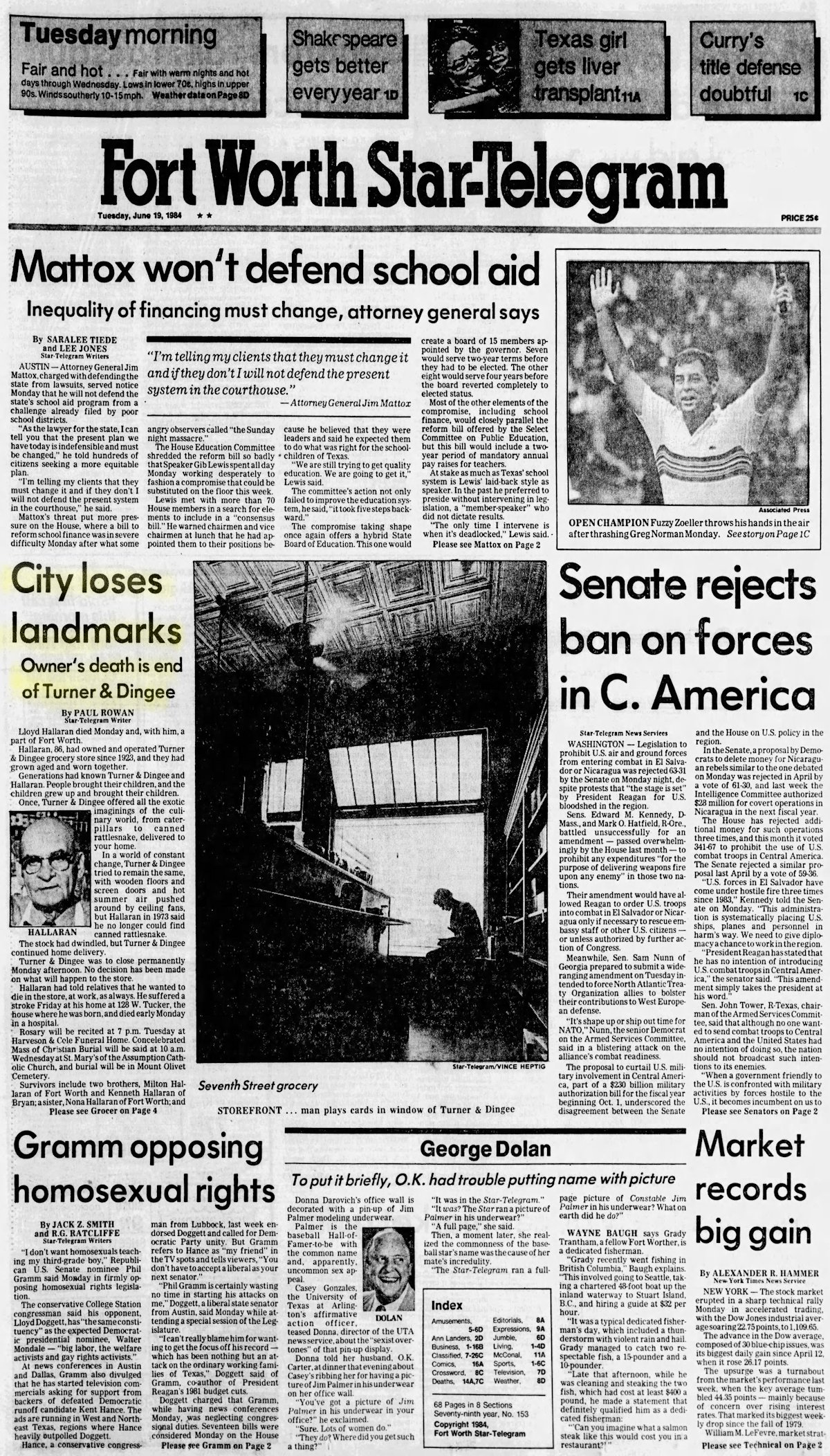

In 1984 Lloyd Francis Hallaran died. He was eighty-six. His store was named “Turner & Dingee,” but it as rightfully could have been named “Turner & Dingee & Hallaran.” When Lloyd Hallaran had hired on at Turner & Dingee in 1917 the grocery store already was the oldest in town. As owner he had added more than forty years to that longevity.

Mayor Pro Tem Herman Stute, a family friend, said of Hallaran, “Going to that store every day was just his life. He never took a vacation. The joy of living was being in that store. His work was his vacation, and his vacation was his work. He had compassion for everybody. He’d see some of those guys that were winos or just kind of hanging in the street . . . he’d let them in back of the store. Others he’d let sit on the window seat. I don’t know another guy in town that would let people just sit and not buy anything. I never saw Lloyd turn any of them away.”

Hallaran was almost universally described as generous and gentle.

He delivered groceries to shut-ins, gave sandwiches to those without money, let people loiter in the store just because it was so loiterable.

In a more problematic act of charity, as Stute alluded, Hallaran sold wine at the store’s back door to the Mogen David 20/20 fraternity—until the day a female member of adjacent First Methodist Church found an overserved stranger sleeping it off in her car. Hallaran had to hire a lawyer to retain his liquor license.

After Lloyd Hallaran died, brother Milton, then eighty-five, and older sister Nona, eighty-nine, kept the store open another two years but mostly just to liquidate stock and to learn to let go. They hung out the “Closed” sign for the last time in 1986.

And so a century of history went on sale as the contents of the Turner & Dingee building were sold, lock, stock, and calf’s-foot jelly.

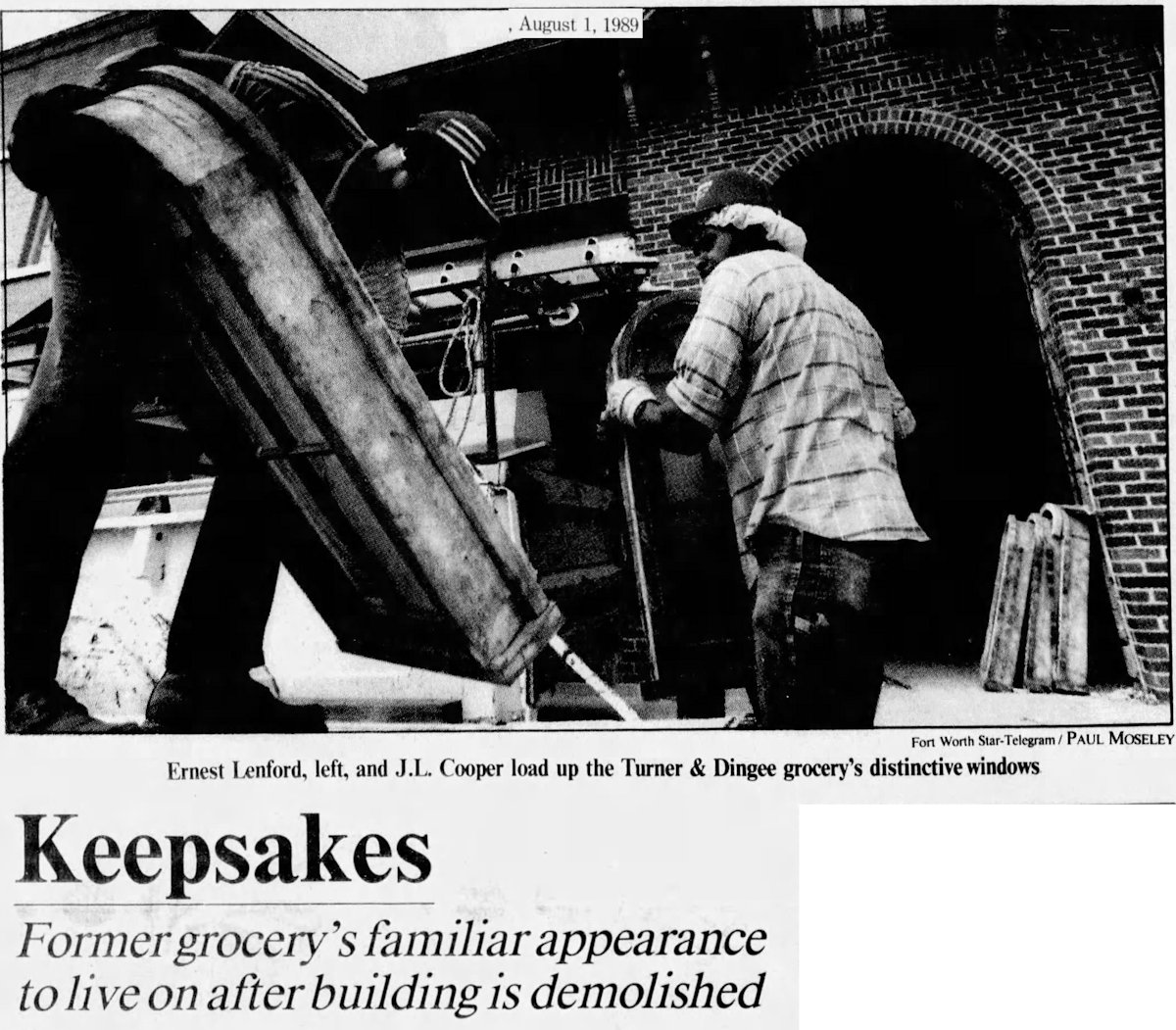

The Turner & Dingee building was demolished in 1989. Hearne Wrecking Company, whose crowbars and sledgehammers had administered the last rites to so many Fort Worth landmarks, made the lot at 800 West 7th Street look as if Turner & Dingee had never existed.

The Methodist church bought the property, where now stands a parking lot.

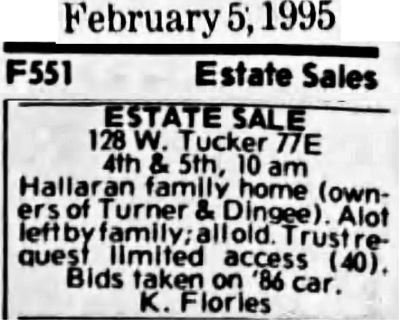

Brother Milton died in 1993, sister Nona in 1995. The Hallaran siblings had lived their entire life in a house built in 1887 at 128 West Tucker Street on the near South Side. The siblings lived with their widowed mother and never married. Nona and sister Mary (“Mae”) taught in Fort Worth public schools for decades. The Hallarans are buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

And so more history was sold via a classified ad.

But the 1887 Hallaran house was spared. In 1997 it was sawed into six parts, moved to Johnson County, and reassembled.

I see that when rich lawyer and spiritualist John W Wray built the “Spiritualist Temple” at 815 Taylor Street (meant for spiritualist gatherings), visitors to the dedication of the building on June 4, 1899 noted that “The interior of the temple is exquisite, and the furnishings and equipment all that the heart could wish for. One feature noticeable above others was a memorial chair in honor of the memory of Joe K. Turner, recently deceased.” That suggests that Turner was a devoted spiritualist, I think.

Grrr. Couldn’t First Methodist UMC have found a use for this dear old building? Would have been a prize Scout Hut.

Grrr indeed. My understanding is that the church had wanted to buy the property for years and in 1989 consented to preserve it-until an architectural study showed that the “economics” were not good. The church bought the property from an intermediary with the stipulation that the building already be demolished.