By the time he came to Fort Worth for the first time in 1879 he was already a national celebrity. Elvis with a rifle. A Kardashian in buckskin. And he had achieved his fame the hard way: by just print media and word-of-mouth. No radio, no TV, no movies, no YouTube or TikTok or Twitter. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

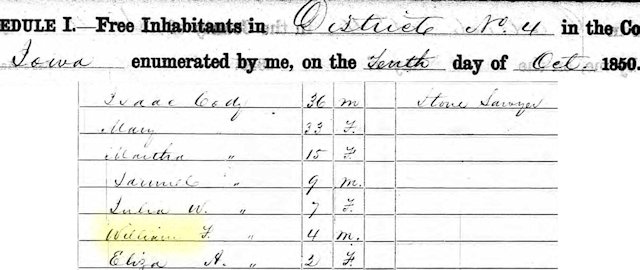

William Frederick Cody was born 1846 in Iowa to Isaac and Mary Cody. Isaac was a stone cutter.

By age eleven William was already making a living in the saddle: He was a messenger boy on a wagon train. He soon joined Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston as an unofficial scout assigned to guide the Army to Utah to suppress a feared uprising by Mormons (1857-1858).

In 1863, at age seventeen, Cody enlisted as a teamster in the Seventh Kansas Cavalry of the Union Army.

After the war Cody served as a scout for the U.S. Cavalry, whose assignment west of the Mississippi included protecting Anglo settlers from the original settlers: Native Americans. The West was a vast wilderness then. There were few cities and fewer roads; mostly just ruts worn by the wheels of emigrant wagon trains. No highway signs, no service station road maps, no GPS navigation systems. A scout was an indispensable soldier to the Army.

General E. A. Carr of the Fifth Cavalry later recalled of Cody: “His eye-sight is better than a good field glass; he is the best trailer I ever heard of; and also the best judge of the ‘lay of country’—that is, he is able to tell what kind of country is ahead, so as to know how to act. He is a perfect judge of distance, and always ready to tell correctly how many miles it is to water, or to any place, or how many miles have been marched.”

In 1866 Cody took a leave of absence from the Army to supply buffalo meat to workers of the Kansas Pacific railroad. He was paid $500 ($11,000 today) a month to provide twelve buffalo a day. As a wholesale hunter Cody is purported to have killed more than four thousand buffalo in eighteen months in 1866-1868.

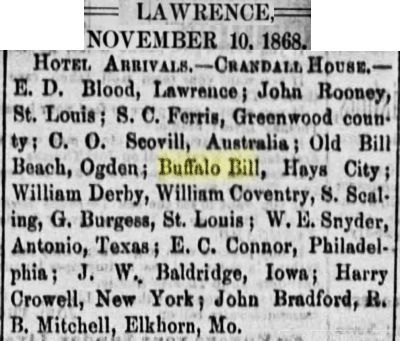

That body count soon earned Cody the nickname “Buffalo Bill.” In 1868 Cody, who lived in Hays, Kansas, signed a hotel register as “Buffalo Bill.”

About that time, this poem supposedly was written by a Kansas Pacific railroad worker:

“Buffalo Bill, Buffalo Bill

Never missed and never will;

Always aims and shoots to kill

And the Company pays his buffalo bill.”

cody 1868 april with haycock.jpg

In addition to hunting buffalo Cody found time—as a “government detective”—to escort some Union Army deserters-turned-robbers to jail. Helping him was deputy U.S. marshal William (“Wild Bill”) Haycock. “William Haycock” was one of the aliases of James Butler (“Wild Bill”) Hickok.

Hickok and Cody had met in Kansas about 1858 when Cody was only twelve. Hickok, like Cody, had been an Army scout. Hickok also was marshal of Hays when Cody lived there.

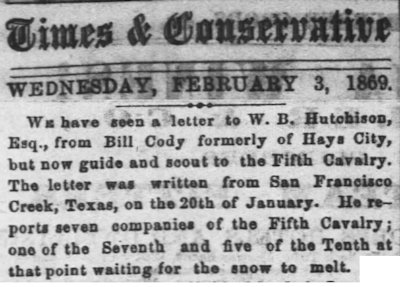

By 1869 Cody was again scouting for the Army. In January 1869 he was among cavalrymen snowed in at San Francisco Creek, a tributary of the Rio Grande in Texas.

San Francisco Creek, seventy miles northeast of Big Bend, remains as desolate as it was when Cody was snowbound there in 1869.

Four months later Cody was back in Kansas. General Carr later recalled of Cody:

“On the 13th of May, 1869, he [Cody] was in the fight at Elephant Rock, Kansas, and trailed the Indians till the 16th, when we got another fight out of them on Spring Creek, in Nebraska, and scattered them after following them one hundred and fifty miles in three days. It was at Spring Creek where Cody was ahead of the command about three miles, with the advance guard of forty men, when two hundred Indians suddenly surrounded them. Our men dismounted and formed in a circle, holding their horses, firing and slowly retreating. They all, to this day, speak of Cody’s coolness and bravery.”

Two months later Carr led his men, including Cody, in the Battle of Summit Springs in Colorado. The cavalry attacked a band of Cheyenne Dog Soldiers led by chief Tall Bull. Cody shot a Cheyenne riding Tall Bull’s distinctive white horse and claimed he had killed Tall Bull. But Cody apparently had killed a different Cheyenne who had been riding the horse of Tall Bull, who had been killed earlier in the battle.

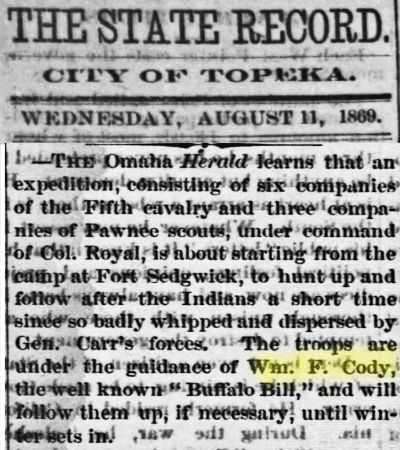

In August 1869 a Topeka newspaper reported that the cavalry of Colonel William Royal was “under the guidance of” “the well known ‘Buffalo Bill.’”

Newspapers increasingly reported on the colorful life of “the well known ‘Buffalo Bill’” as scout and hunter. Even though the mass media of the 1860s was limited to print, men like Cody, who had mastered the West, with its “wild Indians” and wild animals, captured the imagination of people living on farms and in cities, especially back east.

Buffalo Bill was a star in the making.

All he needed was a starmaker.

Enter E. Z. C. Judson.

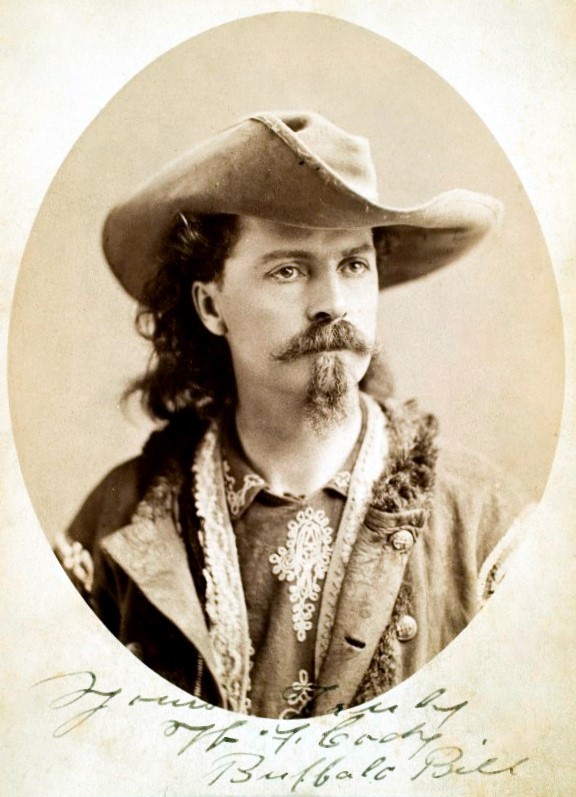

In 1869 Cody, then twenty-three, met Judson, who as “Ned Buntline” wrote dime novels. Buntline was aware of Cody’s growing fame as Army scout, buffalo hunter, and “Indian fighter.” Buntline also saw that Cody’s appearance would lend itself to the engravings that illustrated dime novels. Tall and lean with long hair, Van Dyke beard, and sharpshooter eyes, Cody dressed in buckskin and moccasins and carried a Springfield Model 1866 rifle that was almost five feet long.

Dime novels were melodramatic adventure stories that were often set in the wild West. And for good reason. We must remember that the term wild West is not a term that was coined after the fact. In 1869 the “wild West” was current events, not history. In 1869 America’s West was just that: wild. And the rest of America knew it. Much of the western half of the country had not been granted statehood. Those territories were still being settled by Anglo emigrants, who encountered great hardships. There were Native Americans who had a “not in my backyard” attitude about Anglo settlement. There were dangerous wild animals. There were outlaws holding up trains and stagecoaches.

Who better than Buffalo Bill to face these challenges in a Ned Buntline dime novel?

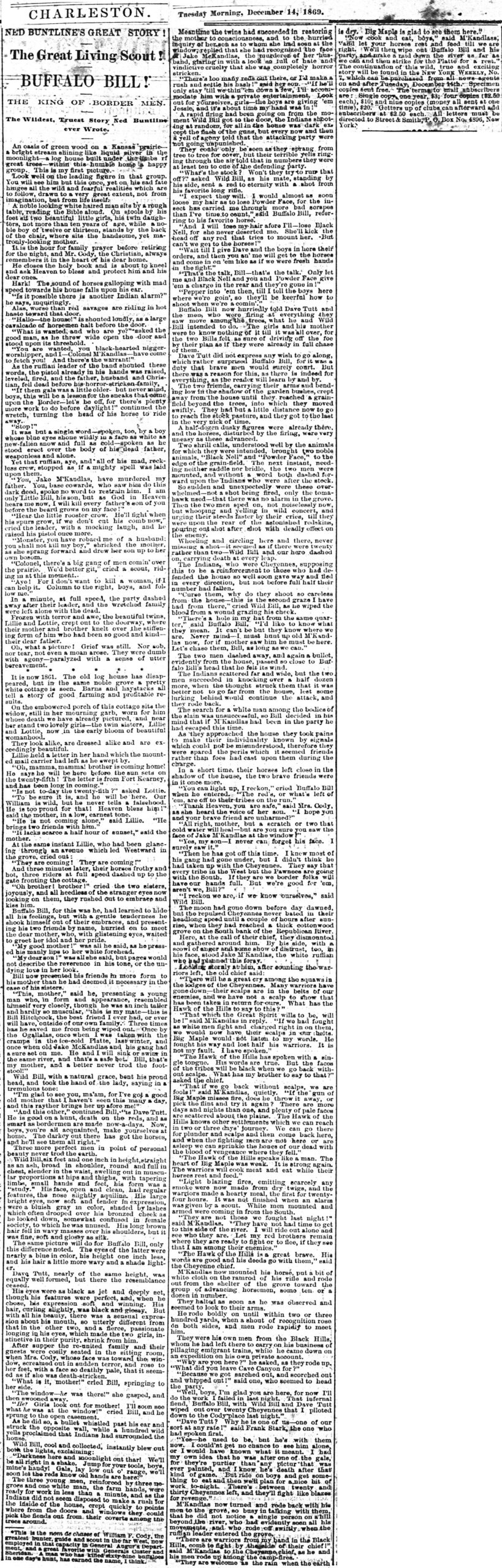

So, soon after meeting Cody, Buntline dashed off Buffalo Bill, King of Border Men, which was serialized in newspapers in December 1869.

Buffalo Bill, King of Border Men was the first of more than five hundred dime novels that would be written about Buffalo Bill by Buntline and others, including, purportedly, Cody himself. The plots of the novels center on the derring-do of Buffalo Bill—America’s first superhero?—as he uses his frontier cunning to outsmart, outride, and outshoot marauding Native Americans and the occasional Anglo ne’er-do-well. The books are not lofty literature—with heavy handed exposition and stilted dialogue—but were popular well into the twentieth century.

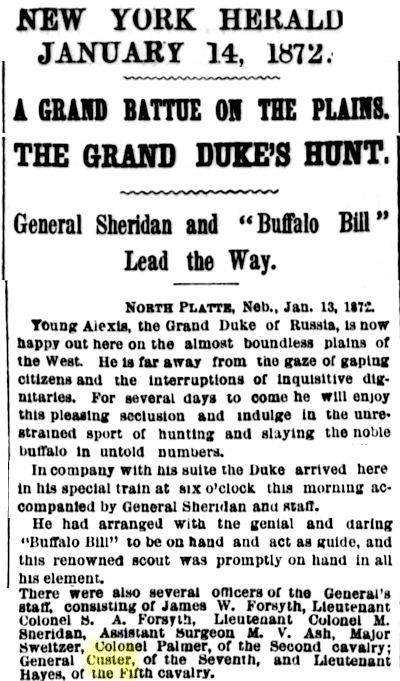

Meanwhile, in 1872 Cody added to his fame when he guided Russia’s grand duke on a hunt in the American West. Taking part in the hunt were generals Philip Sheridan and George Custer. (A battue is a form of hunting in which game is forced into the open by the beating of sticks on bushes.)

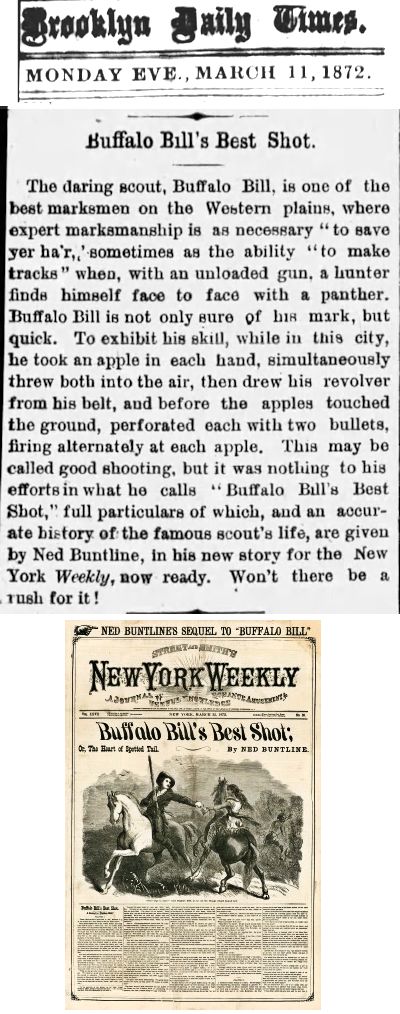

Later in 1872 Cody, while in Brooklyn to promote Buntline’s latest story, Buffalo Bill’s Best Shot, demonstrated his marksmanship by tossing two apples into the air and reducing them to applesauce.

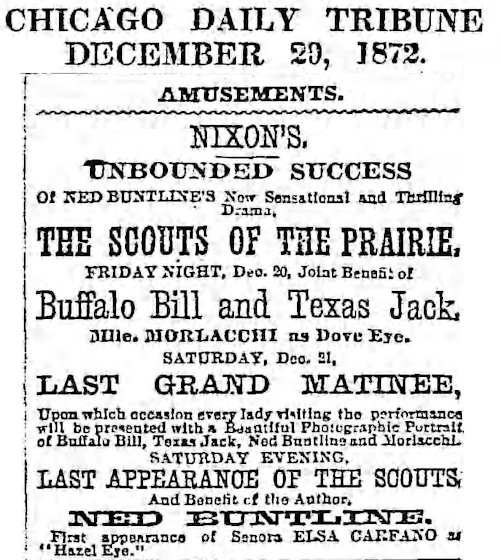

Buntline’s dime novels about Buffalo Bill were selling well in both the United States and England. So, Buntline next wrote—reportedly in just four hours—a stage play about Cody: The Scouts of the Prairie. And who portrayed Cody on stage when the play opened in Chicago in 1872? Why, Cody himself. Buffalo Bill the rugged frontiersman was a reluctant and rigid thespian at first. But he grew to like the new vocation and would remain in the spotlight the rest of his life.

This 1872 photo shows the stars of The Scouts of the Prairie: Ned Buntline, Buffalo Bill, Giuseppina Morlacchi, and John Baker (“Texas Jack”) Omohundro. Omohundro was a frontier scout and cowboy. Morlacchi was an Italian-American ballerina, dancer, and actress. She introduced the can-can dance to the American stage. She was Texas Jack’s wife. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

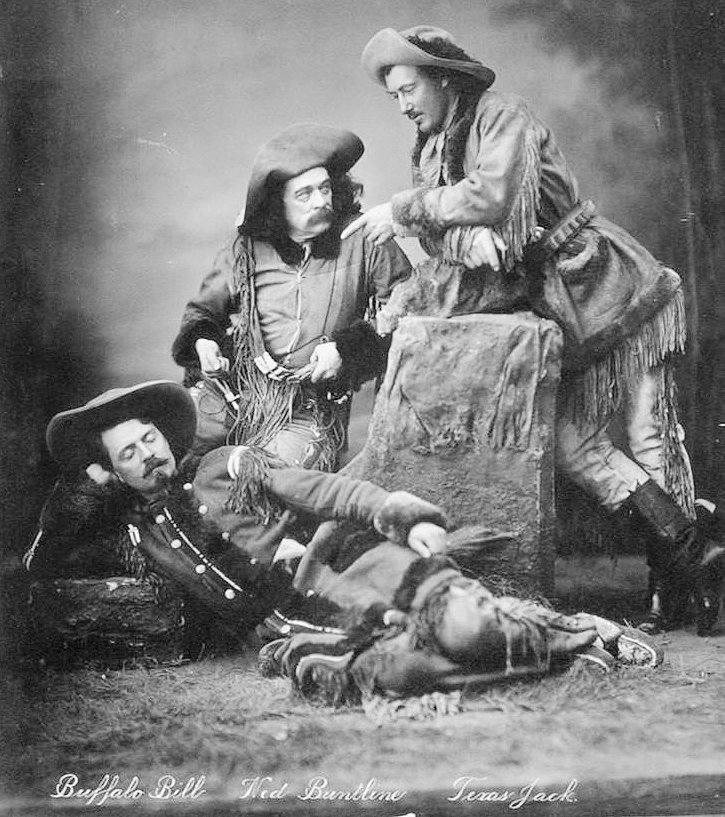

Another publicity photo for the play in 1872: Buffalo Bill, Buntline, and Omohundro. (Photo from Wikimedia.)

(Wyatt Earp biographer Stuart Lake claimed that Buntline in 1876 commissioned from the Colt Manufacturing Company five long-barreled Buntline Special revolvers, which he presented to lawmen Earp, Bat Masterson, Bill Tilghman, Charlie Bassett, and Neal Brown. Earp, Masterson, Bassett, and Brown, along with Luke Short, in 1883 would be members of the Dodge City Peace Commission. Many historians doubt Lake’s claim.)

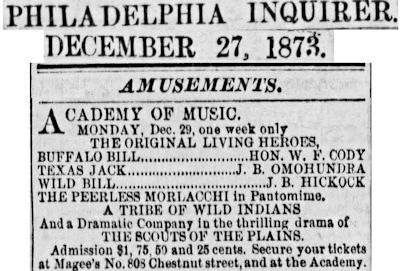

In 1873 Buffalo Bill outgrew Ned Buntline and formed his own theatrical company, the Buffalo Bill Combination. Cody persuaded his old friend Wild Bill Hickok to join the company. Hickok was in debt and needed the money.

The combination’s first play was The Scouts of the Plains. Note the “Hon.” before Cody’s name. In 1872 he had apparently been elected to the Nebraska state legislature. But a recount showed that he had lost. He never took office but kept the “Honorable” title that came with the office.

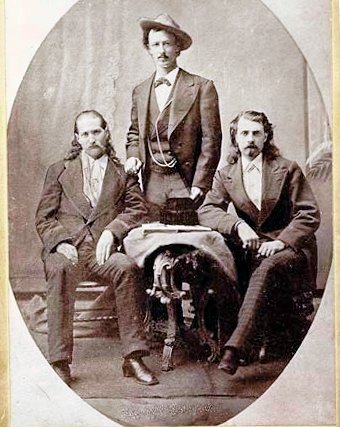

All duded up, the stars of The Scouts of the Plains: Wild Bill, Texas Jack, Buffalo Bill. During performances of the play Cody and Hickok demonstrated skills of the frontier scout, including shooting targets on stage with real bullets. But Hickok was not comfortable in the spotlight. In fact, he often hid behind scenery and during one show shot at the spotlight—with real bullets—when it focused on him. He soon left the company. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Cody in his career had faced belligerent Native Americans, wild buffalo, and freezing winters, but never before had he faced . . . drama critics.

The Wilmington, North Carolina newspaper reported that the Augusta, Georgia newspapers declared the Buffalo Bill Combination to be a “demnition frod” (damned fraud).

Likewise the Chicago Times: “On the whole, it is not probable that Chicago will ever look upon the like again. . . . Such a combination of incongruous drama, execrable acting, renowned performers, mixed audience, intolerable stench, scalping, blood and thunder, is not likely to be vouchsafed to a city a second time, even Chicago.”

Other reviews included these phrases: “maundering imbecility,” “everything was so wonderfully bad it was almost good,” “farcical monotony,” “meagre dramatic talent . . . weakness of voice and nervousness of deportment,” “atrociously bad . . . beneath contempt.”

Ouch.

The critics may have held their noses, but the masses bought their tickets. The success of the plays, Richard Slotkin writes in Gunfighter Nation, showed “the public’s deep and uncritical enthusiasm for ‘the West.’”

Cody about 1875. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

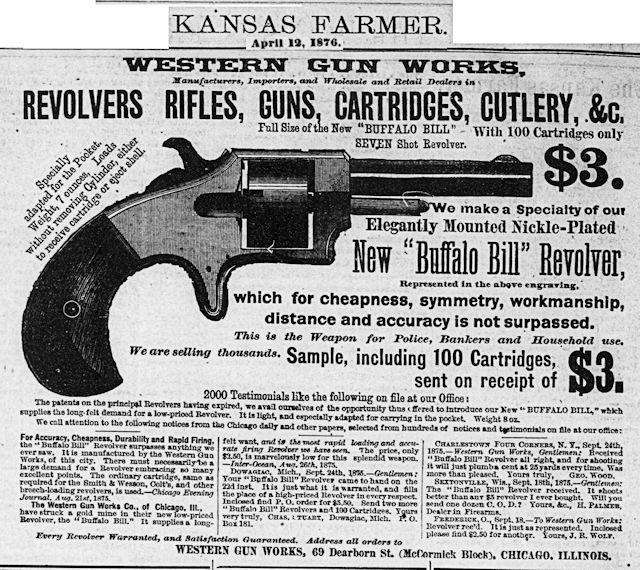

A nineteenth-century example of celebrity endorsement.

By 1876 Buffalo Bill was the star of stage and battlefield: He trod the boards during the winter, scouted for the Army during the warm months.

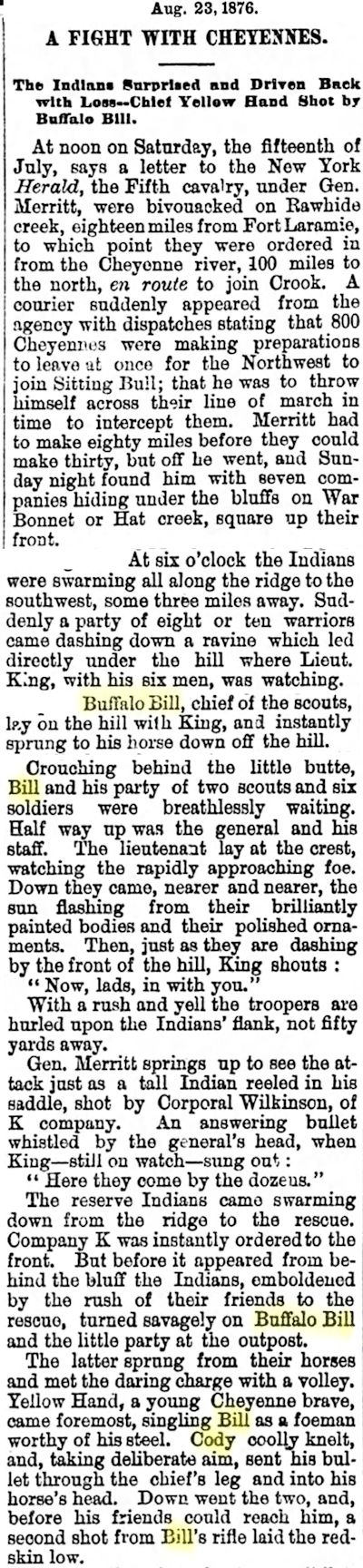

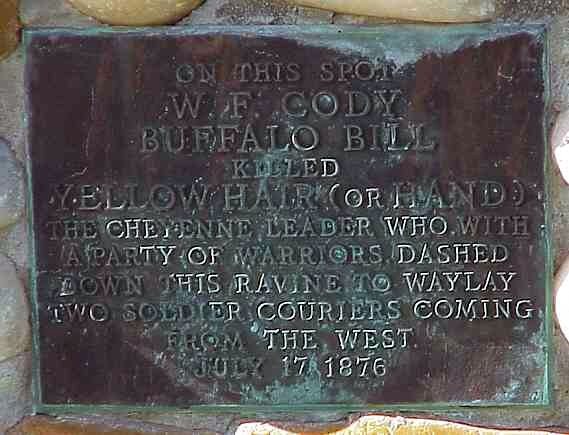

On July 17, 1876, three weeks after the Battle of Little Bighorn, Buffalo Bill guided Colonel Wesley Merritt’s Fifth Cavalry as it fought with Cheyenne warriors at Warbonnet Creek in Nebraska. Cody shot and killed Cheyenne chief Yellow Hair (sometimes translated as “Yellow Hand”) and then scalped him. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

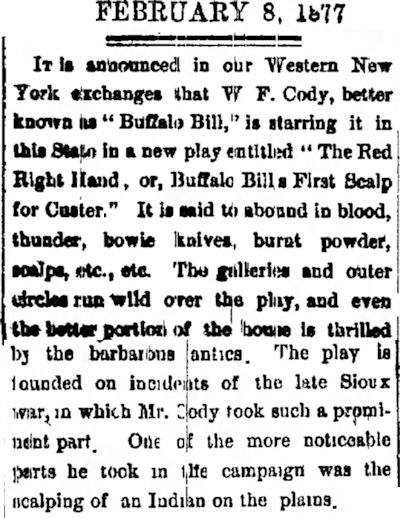

Returning to the stage, Buffalo Bill presented the play The Red Right Hand, or, Buffalo Bill’s First Scalp for Custer, a melodramatic reenactment of Cody’s encounter with Yellow Hair. Cody displayed Yellow Hair’s scalp, feathered war bonnet, knife, saddle, and other possessions.

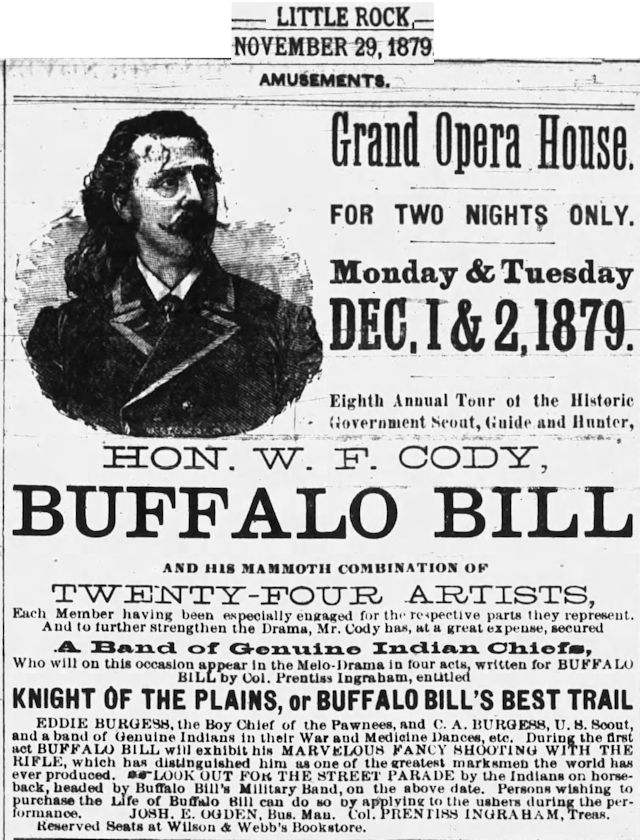

By 1879 Cody, then thirty-three, had stopped scouting for the Army and was devoting all his time to his Buffalo Bill Combination. In the beginning the company had toured mostly the larger cities of the East. But by 1879 the company was touring farther west as expansion of the railroads made travel practical.

Also by the late 1870s newspaper ads were illustrated. Now readers could see what the “historic government scout, guide and hunter” looked like.

By December the company had reached Arkansas. The residents of Little Rock on December 1 and 2 saw a street parade featuring “Indians on horseback, headed by Buffalo Bill’s Military Band” and the drama Knight of the Plains, or, Buffalo Bill’s Best Trail, during which Cody the shooting star exhibited “his marvelous fancy shooting with the rifle, which . . . distinguished him as one of the greatest marksmen the world has ever produced.”

Copies of Cody’s just-finished autobiography (he was thirty-three), The Life of Buffalo Bill, also were for sale.

As the year 1879 drew to a close the Buffalo Bill Combination had appeared in ninety cities. In each town the show was exciting for its audiences, but the pace of touring was grueling for the company. After each show Cody and the rest of the cast and band members and stage hands and animals loaded onto railroad cars and moved on down the tracks to do the next street parade, the next stage show, the next town:

November 26, Jackson, Tennessee.

November 28-30, Memphis.

December 1-2, Little Rock.

December 3, Shreveport.

On December 4, 1879 the next town would be Fort Worth.