He was no different than a million other young men in 1941: farmers or clerks one day, soldiers the next, behind a plow or a desk one day, behind the barrel of a machine gun or the turret of a tank the next in places they had never heard of before, facing dangers they had never imagined from people they had never met, summoning gumption they had never known they had.

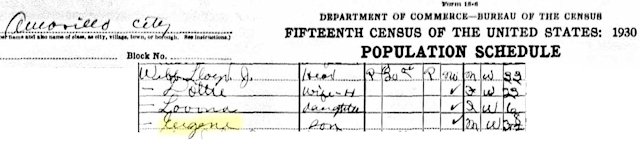

Eugene Lloyd Webb, the son of a railroad steamfitter, dropped out of Amarillo High School in September 1941—two months before his eighteenth birthday, three months before Pearl Harbor—and joined the Marines.

Nine months later the kid from the Panhandle was a Son of Satan—a corporal in Marine Scout Bomber Squadron 241. On June 4-6, 1942 the squadron fought in the Battle of Midway in the north Pacific Ocean. The squadron lost twenty-three of its thirty aircraft and twenty-two of its men. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Corporal Webb, eighteen, manned the radio and the rear machine gun of a dive-bomber plane during the battle and was credited with shooting down at least two Japanese fighter planes.

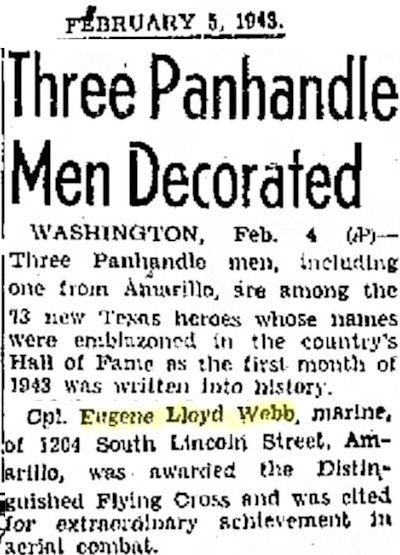

Webb was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross “for extraordinary achievement” at the Battle of Midway: “In a determined attack against the invading Japanese Fleet, Corporal Webb, serving as rear-seat free machine-gunner, maintained fire in the face of overwhelming enemy fighter opposition and fierce anti-aircraft barrage. . . . His courage and devotion to duty during these actions were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

Webb later was promoted to the rank of sergeant, survived the war (sending much of his Marine pay home to his parents in the form of war bonds), finished his service at Marine Corps Air Station El Toro in California, and returned to Amarillo in 1945.

And then, after surviving four years of war, dive bomber Eugene Lloyd Webb had to survive life as a civilian.

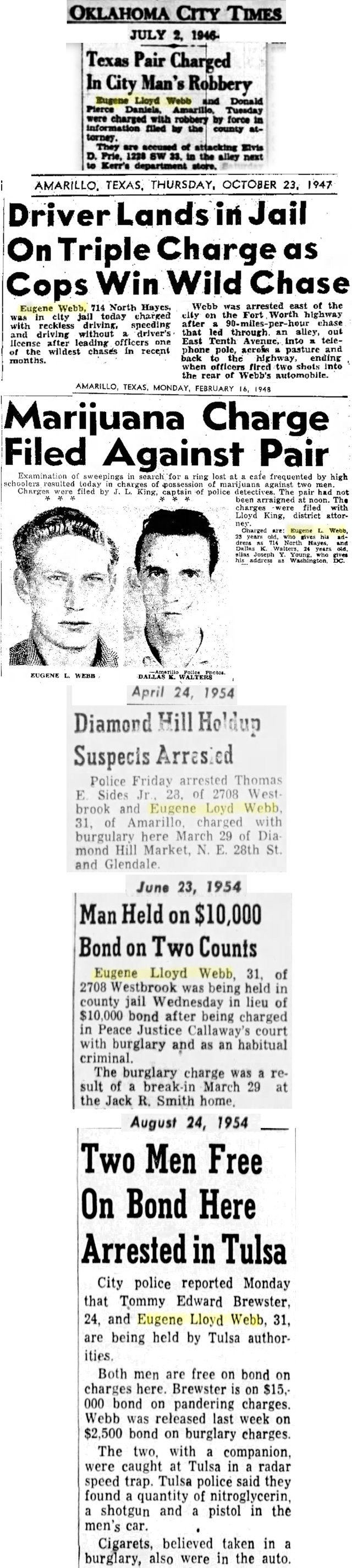

Webb soon began a downward spiral. He was convicted of marijuana possession in 1949, of forgery of a narcotic prescription in 1951.

In 1946 he was arrested for burglary.

In 1947 he was arrested for reckless driving after leading police on a chase of up to ninety miles per hour during which two other occupants of Webb’s car were thrown from the car when it hit a telephone pole. The chase ended when police officers shot out the rear tires of his car.

Then came another arrest for marijuana possession in 1948.

Twice in Fort Worth in 1954 he was charged with burglary and with being a habitual criminal.

Also in 1954 he was arrested in Tulsa for carrying nitroglycerin, a pistol, shotgun, rifle, burglar tools, and 317 cartons of cigarettes (valued at $15,000 today), which police suspected had been stolen.

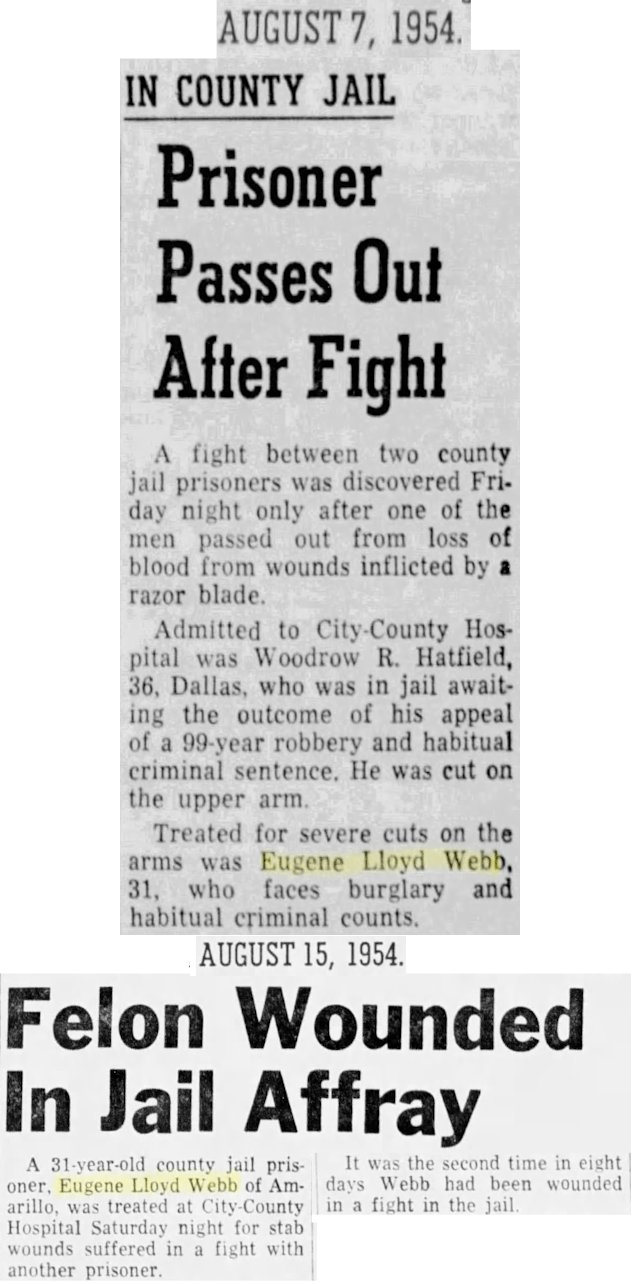

In 1954 while in jail in Fort Worth Webb got into two fights in eight days. The weapon in the first fight was a razor blade. In the second fight the weapon was a spoon whose handle had been sharpened by rubbing it on the concrete floor of a jail cell.

By December 1957 Webb was described by an Oklahoma newspaper as a member of “the ‘elite’ of the Fort Worth underworld” after he was arrested with the “notorious” Clifton Earl Hudspeth, said to have been “associated” with Fort Worth underworld overachievers Tincy Eggleston and Cecil Green.

Hudspeth and Webb were stopped in Temple and found to be in possession of burglary tools: a jimmy bar, six-pound sledge hammer with sawed-off handle, punches, electric drill, high-speed drill bits, hacksaw blades, wire cutters, a three-pronged grappling hook with thirty feet of rope knotted every two feet, flashlights, galoshes, and tennis shoes.

The Amarillo Globe-Times called hometown boy Webb “one of the most dangerous thugs in the Panhandle area.”

Then came 1958, and Eugene Lloyd Webb came “this close” to making it through the year without getting his name in headlines.

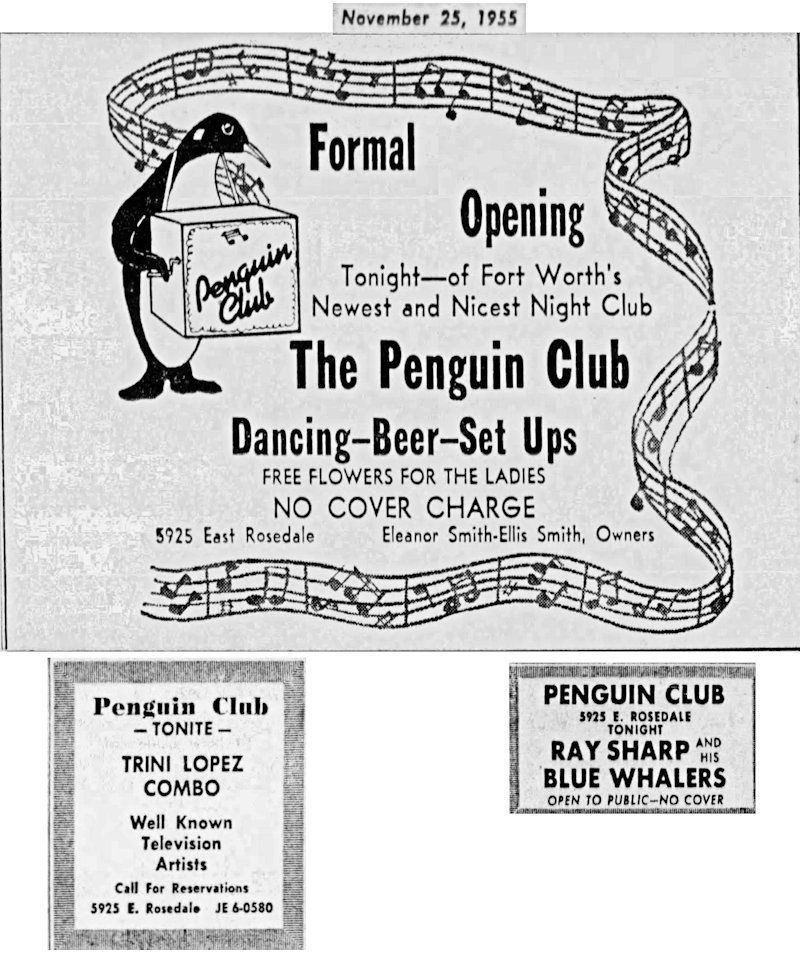

But three days short of New Year’s Eve, Webb got a head start on his celebrating with a bottle of vodka at the home of friends Donald and Lita Jo Daniels at 3118 Avenue M. The three then went to the Penguin Club at 3925 East Rosedale Street.

The banner headline of the December 29 Star-Telegram read: “Bystander Killed in Gunplay/Another Wounded by Ex-Con.”

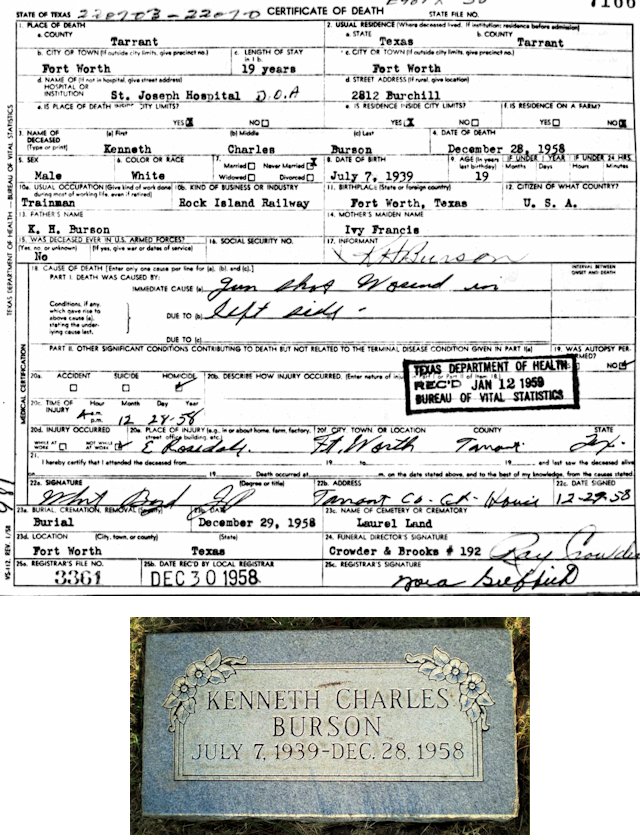

The ex-con was Eugene Lloyd Webb. The bystander was Kenneth Charles Burson, nineteen. The wounded was Bobby J. Fogle, twenty-seven.

Police said that about 1 a.m. on December 28 club staff switched on the lights in the club to signal closing time. Webb was sitting alone after his friends Donald and Lita Jo Daniels had left the club. Another club patron, Howard Aiken, twenty-one, started a fight with patron Fogle. Club staff ordered the two men outside. The two men went outside, accompanied by Burson, Fogle, and others. Fogle came back into the club, and Webb shot him in the hip.

Then Burson came back into the club, and Webb shot Burson. Burson and a friend, James Ford, walked out of the club to their car. But Burson fell to his knees, pleading, “Help me, I’m shot.”

Ford went back into the club to telephone an ambulance. Webb shot at him, too, but missed.

“Nobody’s going to call an ambulance,” Webb said.

Burson’s father, K. H. Burson, said his son “was an innocent bystander. I’ve talked with his dates and others who were there,” he said. “They all said he was just standing there when he was shot.”

Fogle said he didn’t know Webb or Burson and knew his antagonist, Howard Aiken, only “by sight.”

Police arrested Webb, who gave his address as 2725 Gordon Street on the South Side.

The Star-Telegram wrote of Webb: “His FBI record is a fat three-page document of arrests” and Webb is “high on the list of known criminals of the Texas Department of Public Safety.” Webb had served three prison sentences by the time of the shooting.

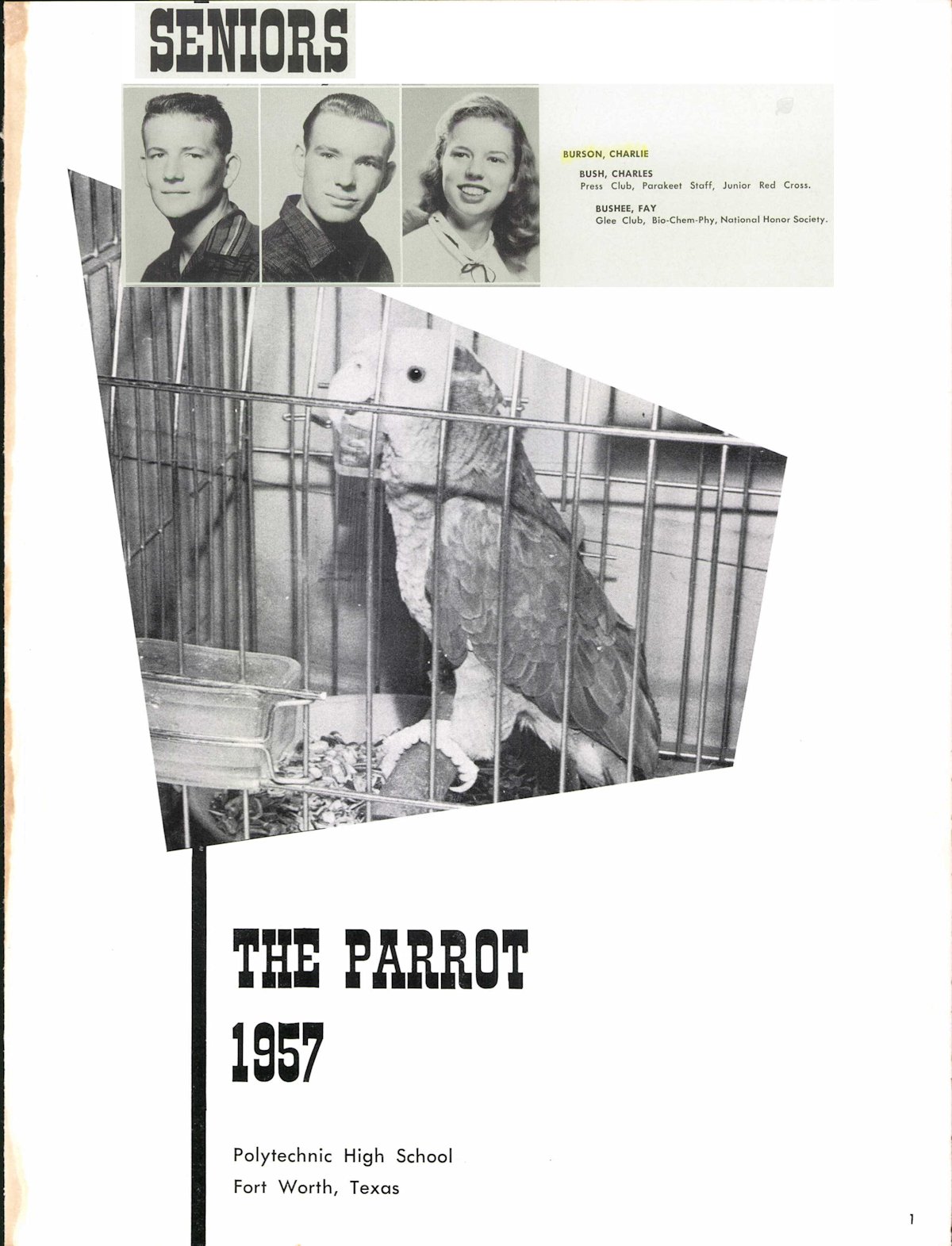

Kenneth Charles Burson lived with his family at 2812 Burchill Road in Poly.

From his front porch Burson could see the weathervane and cupola of Poly High School, where he had graduated in 1957. In 1958 he worked as a brakeman for the Rock Island railroad.

Burson was buried in Laurel Land cemetery.

The Penguin Club had opened in 1955 and featured Metroplex musicians.

Even before Eugene Webb set foot in the Penguin Club, it had a colorful reputation. It had been bombed twice in 1957, and a third attempt failed when the fuse fizzled before it could detonate five sticks of dynamite. In 1958 the son of the club owner “clubbed” a Liquor Control Board investigator.

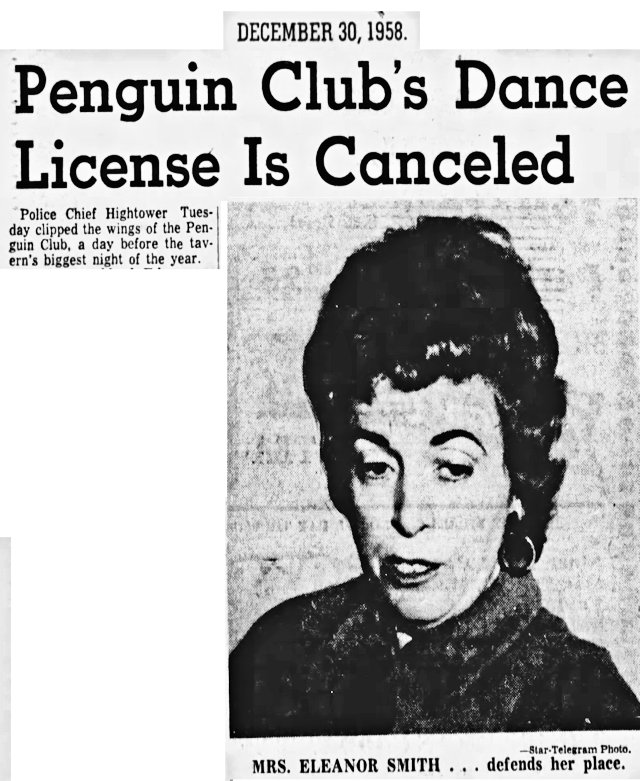

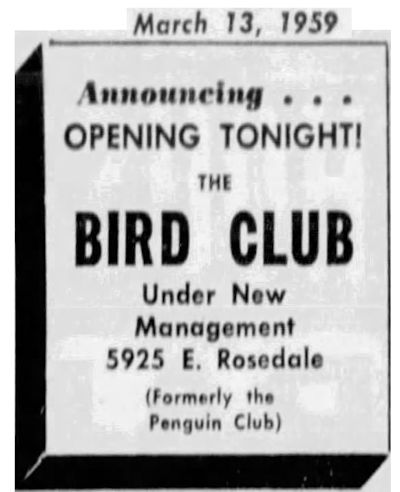

After the Burson slaying, the city did not shut down the Penguin Club but did revoke the club’s dance license, which was tantamount to driving a stake in the club’s cash register, especially just before New Year’s. On January 1, 1959 a sign reading “For Sale or Lease” hung on the front door.

Fort Worth police vice squad sergeant Oliver Ball said prostitutes and procurers frequented the club.

Ball also said the club operator, Mrs. Eleanor Smith, knew Eugene Webb on sight and should have refused to let him into the club.

Mrs. Smith countered that Webb had been turned away when he first tried to enter the club but had later slipped in undetected.

Ball said that club employees should have summoned police to eject Webb.

Police Chief Cato Hightower also said club employees did not notify police of the shooting. He said police learned of the shooting only when a police officer’s son was stopped for speeding while in pursuit of Webb as he fled the club.

There was no “did he or didn’t he?” mystery about the Burson murder.

Eugene Webb pleaded not guilty but never denied shooting Burson.

“I did not intentionally kill that boy. I’m awfully sorry it happened.”

Even Webb’s defense attorneys—prominent local criminal defense attorneys Ronald Aultman and Randell Riley—did not deny that Webb killed Burson.

Webb was charged with murder with malice. District Attorney Doug Crouch said he would seek the death penalty.

The only mystery was the sentence that the jury would assess: death or life in prison.

Aultman and Riley pleaded for leniency for their client, initially arguing that Webb was “blind drunk” and did not know what he was doing at the time of the shooting.

Riley said, “The facts will show that there was no malice and that, if any thing, it would be murder without malice because of the heavy drinking by all parties. There was no intent to kill.” (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Star-Telegram Collection.)

Webb’s trial began on February 9, 1959 . . .

And ended on February 10.

The judge declared a mistrial before the first witness was called after the Star-Telegram printed a story reporting that Webb’s attorneys told DA Crouch that Webb would plead guilty in return for a sentence of life in prison, not death.

Webb’s attorneys protested to the judge that the news story would prejudice potential jurors. The judge agreed.

Crouch denied receiving such an offer from Webb. Crouch said he would have rejected the offer anyway because he felt he had a solid case for the death penalty.

In 1959 the Star-Telegram identified African-American jurors.

As Webb’s second trial got under way, on March 25 a witness testified that he had seen Webb pick a patron’s pocket in the Penguin Club shortly before the shooting.

The witness added: “Webb didn’t fumble around like a drunk when he picked that man’s pocket. It was a smooth job.”

Webb’s attorneys protested that such testimony would prejudice jurors against Webb.

The judge agreed and declared a second mistrial.

Meanwhile, in March 1959 the club was reborn as the “Bird Club.”

During Webb’s third trial Charles McCrory, twenty, a witness for the prosecution, testified that about forty-five minutes before Eugene Webb shot Kenneth Charles Burson in the Penguin Club, McCrory and Burson were sitting at a table about eight feet from Webb when McCrory saw Webb load a revolver and spin its cylinder.

McCrory and another witness, James Ford, said they later saw Webb shoot Burson.

McCrory recalled: “The defendant made a motion like to hit Charley [Burson] with the gun. Charley backed up, and the defendant put the gun almost up against Charley and fired. Then the defendant waved the gun and told everybody to stay back.”

Friends, including Ford, carried Burson to the parking lot and placed him on the ground. Ford went back into the club to call an ambulance but was prevented by Webb.

McCrory said Webb told Ford, “There ain’t no —- going to call an ambulance.”

In May, Webb was found guilty and sentenced to death.

A month later a third mistrial was declared after Webb’s attorneys discovered that a juror had failed to disclose his 1941 conviction for . . . wait for it . . . cattle rustling.

Webb’s death sentence was thrown out and a fourth trial ordered.

That trial began in November. There was a slight blip when prospective juror Mrs. Irene Clark told prosecutors that she had no qualms about the death penalty and was not familiar with the case but then, after she was selected as a juror, told the judge that she did have qualms about the death penalty and had discussed the case at a bridge party.

Two days later prosecution witness Bobby J. Fogle, himself an ex-convict, was arrested because he was wanted in Dallas for passing a worthless check.

Webb’s attorneys wanted to tell the jury that a star witness for the prosecution had been arrested, but the judge would not allow such testimony.

And to complete the colorful cast of witnesses, defense witness Cynthia Martin Pack, nineteen, was brought to court from Longview, where she was being held in the Gregg County jail for smuggling a loaded pistol to her incarcerated boyfriend.

Witnesses, prosecutors, and defense attorneys could piece together what happened that night at the Penguin Club but not why.

Not even Eugene Webb himself could say why. He never took the witness stand.

Webb’s attorneys during the previous three trials had argued that Webb was too drunk to know what he was doing when he shot Burson.

In the fourth trial Webb’s attorneys tried to shift the blame, arguing, the Star-Telegram wrote, that “Burson, as a minor, had no business being in the club.”

The attorneys also found two witnesses who painted Burson as less than a purely innocent victim.

Robert MacDougall, who was manager of the club on the night of the shooting, testified that he saw Burson enter the club and take a swing at Webb. MacDougall recalled that he shoved Webb out the front door to stop the confrontation and that Webb said to MacDougall, “Why did he [Burson] have to jump on me?”

MacDougall said that Burson “jumped on” Webb and that the assault “made the gun go off.”

Another witness, F. M. Cooner, testified that Burson “bumped into” Webb and that the two men “were sort of grappling there” immediately prior to the shooting.

The testimony of MacDougall and Cooner was at odds with that of prosecution witnesses, all of whom said Webb shot Burson without provocation.

On November 13 the case went to the jury, which retired for the night without reaching a verdict.

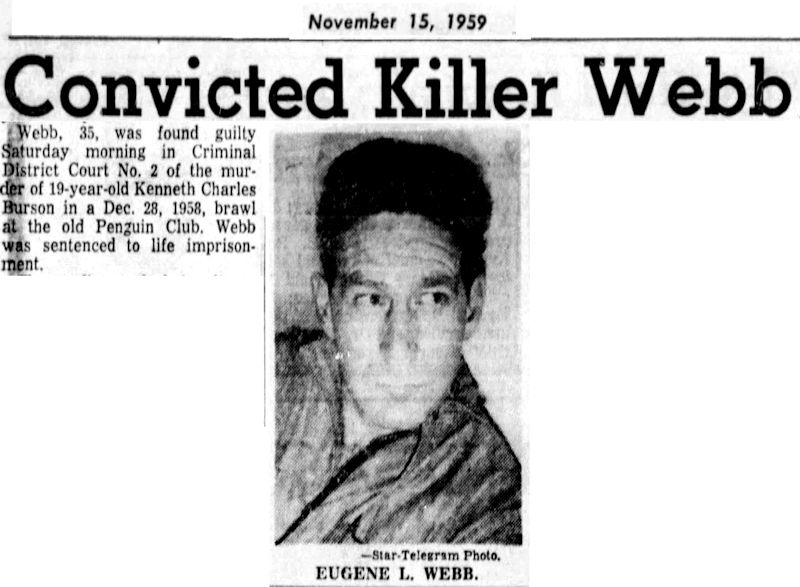

Early the next morning the jury found Eugene Lloyd Webb guilty of murder with malice and sentenced him to life in prison.

The decorated dive bomber of World War II had crashed.

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade

I remember the Penguin Club where Rosedale made a northeastern swerve to link up with Lancaster (then a part of Highway 80) when we used to go to Dallas….No Turnpike then, only Hwy. 80 and Hwy. 183 (now 10) were direct routes to the evil city in the east….Seems as though I remember hints that the club had an integrated clientele and that may have contributed to lots of chicanery….Don’t know that I was aware of Trini Lopez then, but Ray Sharp was a constant at various clubs….I was younger than 10 then, but my folks talked a lot about the underworld of “little Chicago” Fort Worth….

Dan, I have no memory of the club. I do remember Burson’s younger brother Jimmy. In fact, I last saw Jimmy on his Honda 50 on Burchill Road. I’ll have more on the Penguin Club in an upcoming post.