Four of Fort Worth’s most tangible reactions to World War II were located on the area’s two lakes (Lake Worth and Eagle Mountain). The best-known of the four, of course, were the bomber plant and the adjacent Army Air Forces airfield (later “Carswell Air Force Base”).

Lesser known was the city’s seaplane base.

And least known, perhaps, was the Marine Corps Air Station.

As America went to war against its enemy across the Pacific Ocean, a lot of islands lay between America and Japan.

So, the Marine Corps devised a plan to use amphibious glider airplanes to transport troops.

In June 1942, on a front page dominated by war news, the Star-Telegram announced that the Marine Corps would build the nation’s first inland glider base on 2,400 acres of ranchland on the eastern shore of Eagle Mountain Lake. The base would be the first of three planned for the Marines.

The Fort Worth chamber of commerce, as it had for the bomber plant and the Army airfield, had facilitated the selection of the site by the federal government.

The United States neither dillies nor dallies in time of war. In December 1942, just five months after plans for the base were announced, the $5 million ($86 million today) Marine Corps Air Station was commissioned.

The station had three runways and two seaplane ramps (the water district had lowered the level of the lake to allow construction of the ramps). The ramps were connected to an apron. The apron was connected to a runway by a taxiway.

Buildings included barracks for fourteen hundred Marines, a hospital, a recreation hall, and a six-story control tower.

A military base also needs a railroad connection. Just as a spur of the Texas & Pacific railroad served the bomber plant and the Army airfield, the Marine base was served by a spur of the Rock Island railroad track, which ran along Avondale-Haslet Road a half-mile away.

The base printed its own publication (The Log), fielded a baseball team in the Panther City League, and entered boxers in Golden Gloves matches.

Marines grew their own vegetables for the mess hall tables.

Among the airplanes flown from the base by the Marines’ 71st Glider Group were the Pratt-Read LNE glider (top) and the Grumman J2F Duck amphibious biplane. (Photos from Wikimedia and Wikipedia.)

This matchbook from about 1943 depicts one of the base’s gliders. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

But the Marines glider training program was shortlived. It ended in 1943. In July the Marine base was transferred to the Navy, which used the base to test remote-control aircraft.

But the Navy did not stay at the base long. In April 1944 the base reverted to the Marines. In December 1944 the field became the home of Marine Aircraft Group 53, which was the Marine Corps’ first night fighter group. These Marines trained for aerial combat at night and in poor weather and low visibility. Two night fighter airplanes that operated from the base were the Grumman F6F Hellcat and F7F Tigercat.

In 1944 the base had eighty-four aircraft and two thousand personnel.

Photos from top to bottom: A Marine and his fighter. The base control tower and operations building are visible beyond the propeller blade (1944); three Marines in front of a fighter with the base hangar visible in the background (1944); hangar (1947); base hospital (1943); base buildings including barracks and hangar (1947). (Photos from University of Texas at Arlington Star-Telegram Collection.)

In October 1945, with the war over, the Star-Telegram revealed that in March the Navy’s Mars seaplane had made a secret landing to test the base’s ability to handle large seaplanes (of which the Mars, at seventy-two tons and a wing span of two hundred feet, was the largest). The Star-Telegram said the Mars “dwarfed” the Catalina seaplanes moored at the base.

In 1946 the Marines moved out of the base, and the base was declared to be surplus.

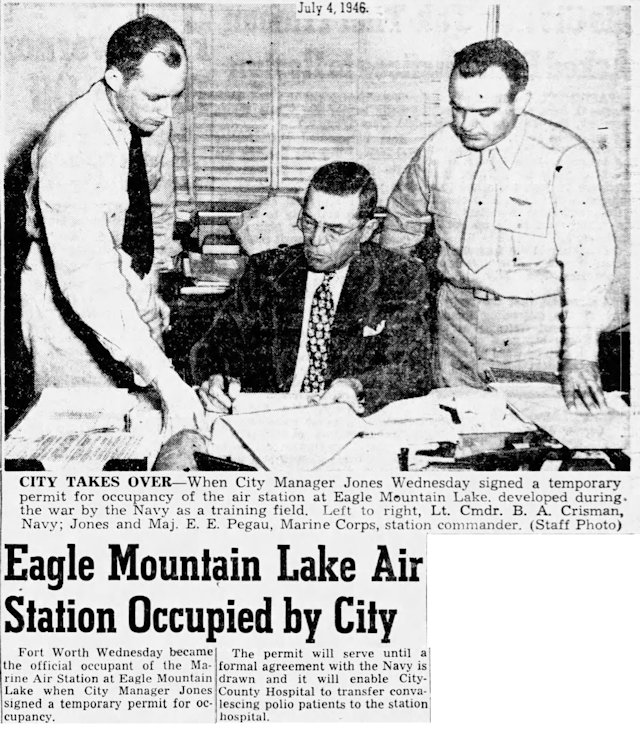

But soon after, the city of Fort Worth moved in: City-County Hospital (later “John Peter Smith Hospital”) transferred some polio patients to the base hospital.

However, the long distance from Fort Worth to the base was deemed unfeasible, and in 1947 the city gave up its lease on the base.

Soon the base got yet another new owner: the Texas National Guard. Fort Worth units of the 49th Armored Division moved into the base.

In 1951 yet another branch of the military used the base as Air Force reservists from Carswell Air Force Base trained at the National Guard base.

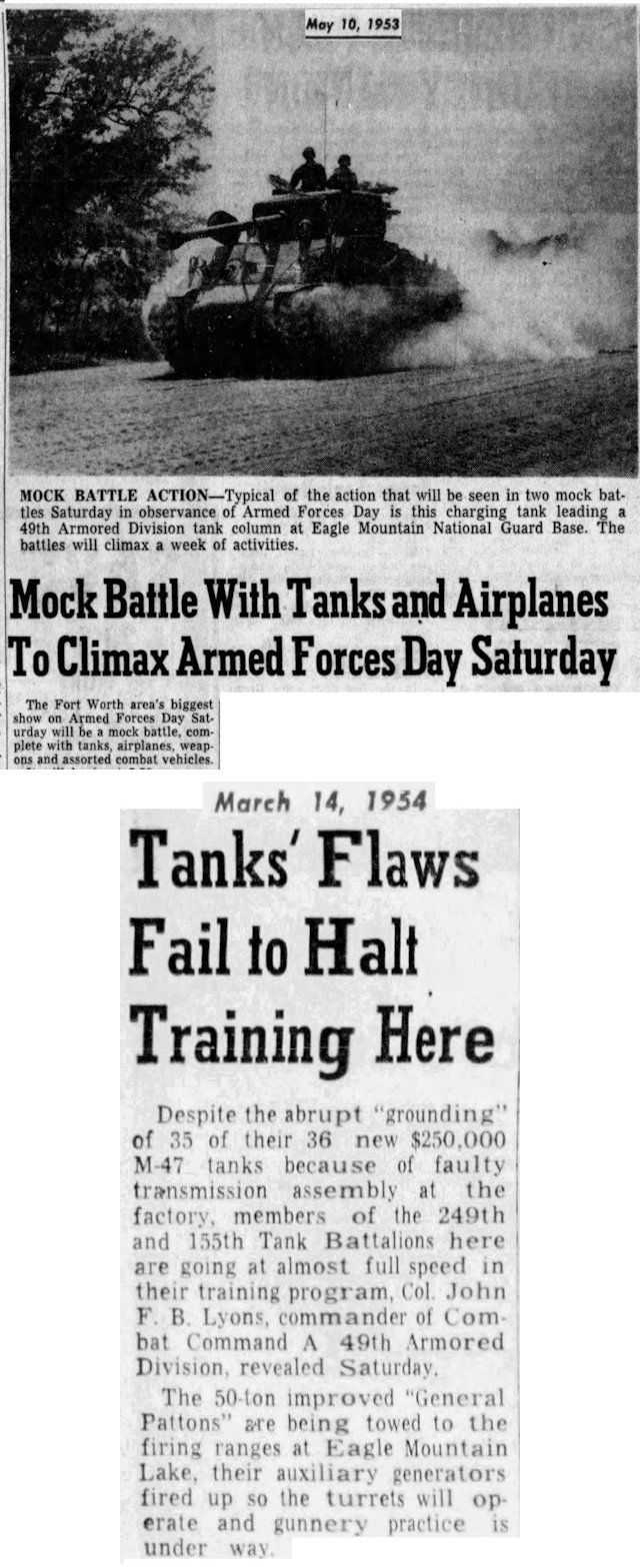

To celebrate Armed Forces Day in 1953 civilian spectators watched National Guardsmen deploy tanks, mortars, airplanes, and Hiller H23-A helicopters, which had been used for medical evacuations during the Korean War.

Radio communications among the participants of the mock battles were broadcast to spectators on a public address system.

In 1954 the base received some of the last M-47 Patton tanks built. (During gunnery practice, Avondale-Haslet Road, which transected the base, was closed to the public.)

WBAP-TV Texas News film footage (no audio):

Field maneuvers, 1953

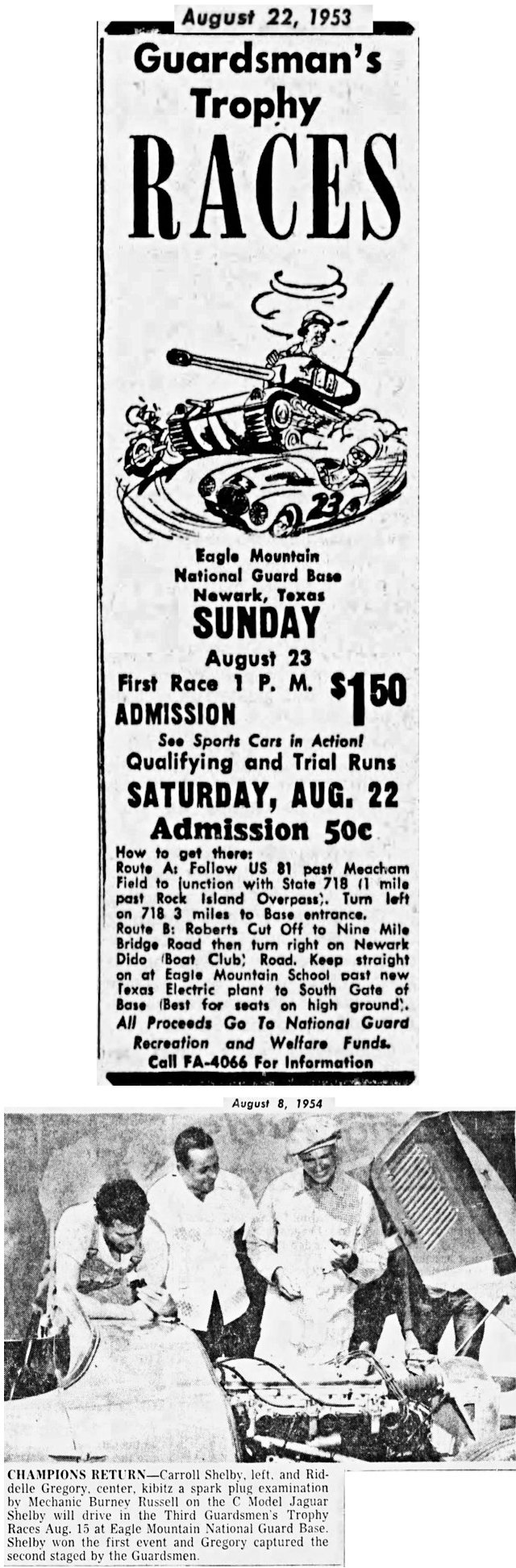

At the other end of the vehicular spectrum from M-47 tanks, during the 1950s the base was used for sports car races. Some of the races were sponsored by the Guard itself. Proceeds benefitted the Guard’s recreation and welfare funds.

Among the racers in 1954 was Carroll Shelby in a Jaguar. The Sports Car Club of America also sponsored races at the base. And the Fort Worth police department sponsored auto races at the base as part of a program to decrease juvenile delinquency. The course distance over the three runways was three miles.

WBAP-TV Texas News film footage (no audio):

Sports car rally, 1953

Sports car rally, 1956

This 1956 aerial photo of the base shows the seaplane ramps and apron (circled), main hangar, control tower, and the railroad spur from the Rock Island track along Avondale-Haslet Road. The base was the home of the 249th Tank Battalion of the 49th Armored Division of the National Guard.

But in 1957 the 249th Tank Battalion moved to the new armory in Cobb Park.

The 49th Armored Division continued to use the Eagle Mountain base as a rifle range, training bivouac area, and auxiliary airfield.

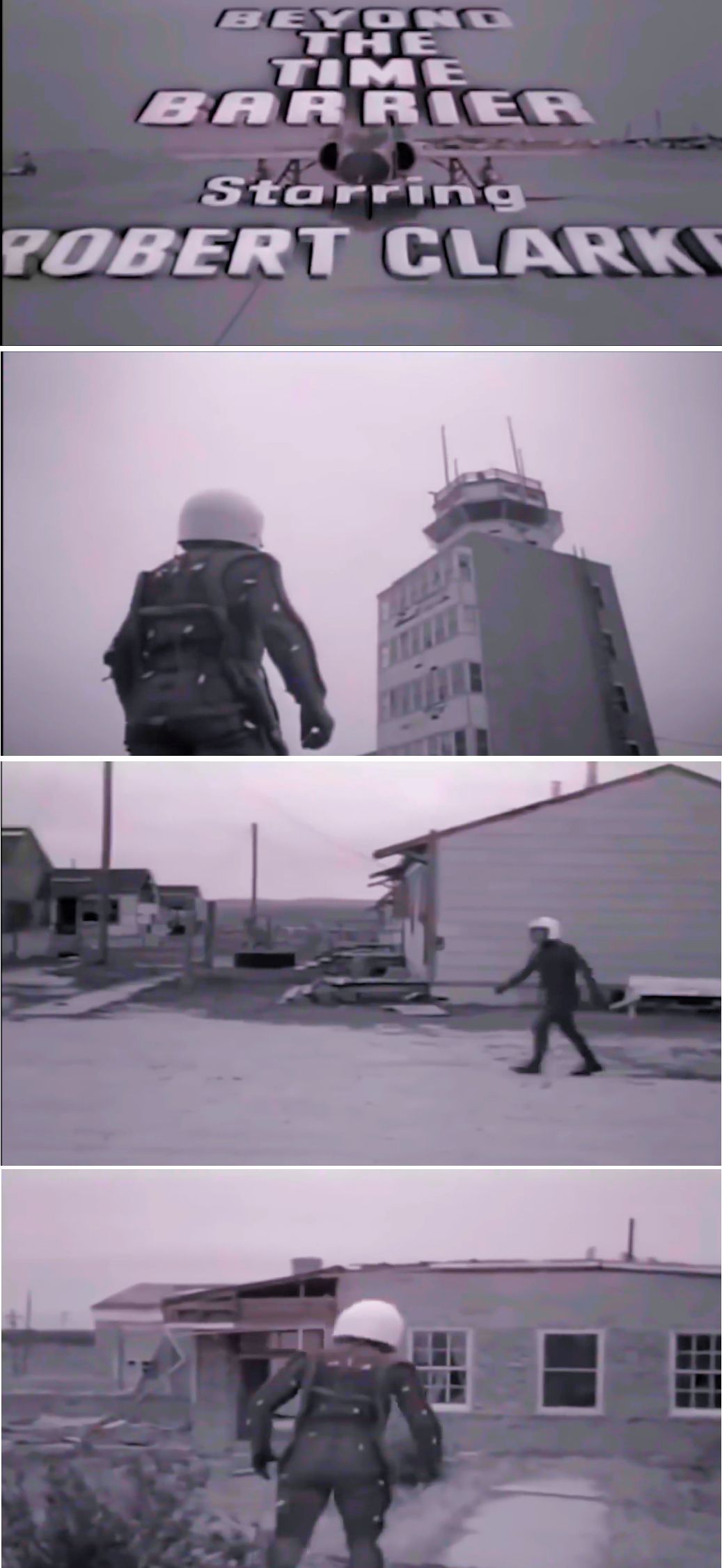

By 1959, although the National Guard still occupied the base, some base buildings, such as the control tower, were unused and had fallen into disrepair. Some of these dilapidated buildings can be seen in the 1960 science-fiction motion picture Beyond the Time Barrier. Other parts of the movie were filmed at Carswell Air Force Base and the state fairgrounds in Dallas.

In May 1960 the base passed to yet another branch of the military, becoming “Eagle Mountain Army Airfield,” a maintenance base for Army airplanes and helicopters, although the National Guard continued to train at the base.

After the Army ended its operations at the base the federal government tried to sell the base in 1965 but received no valid bids.

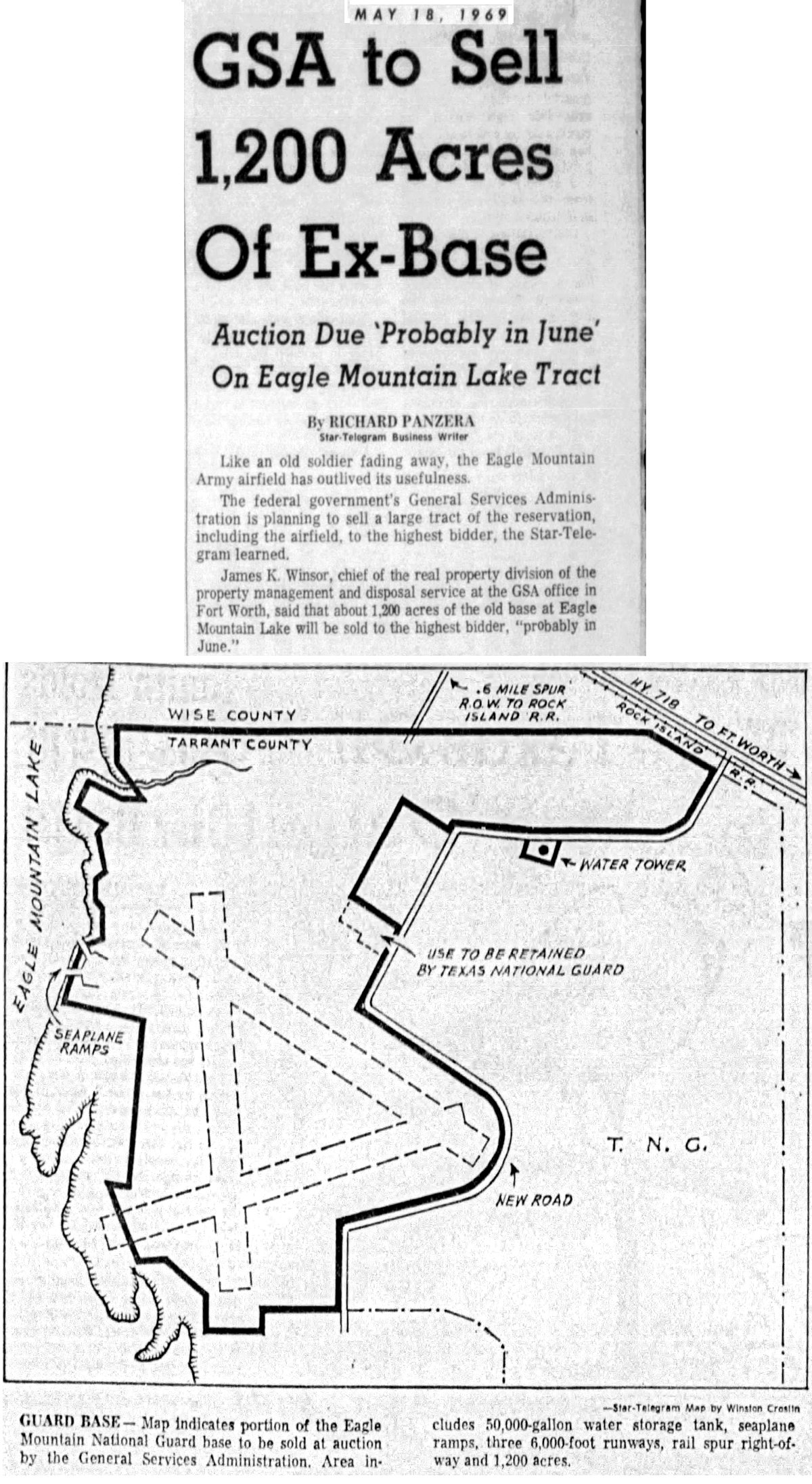

In 1969 the federal government tried again with better results. The General Services Administration auctioned off the western half of the base: twelve hundred acres containing the seaplane ramps, runways, railroad spur, and most of the buildings. An Irving man paid $620,000 ($4.7 million today).

The Texas National Guard retained the unimproved eastern half of the base.

Fast-forward ten years. In 1979 televangelist Kenneth Copeland bought the former base for $4-5 million. He said that when he first saw the land in 1973 “the spirit of the Lord said to me, ‘Yes, this is the revival capital of the world, and you are going to build it.’”

Under Copeland ownership the property once again became the site of races as his ministry sponsored the annual Eagle Mountain Motorcycle Rally.

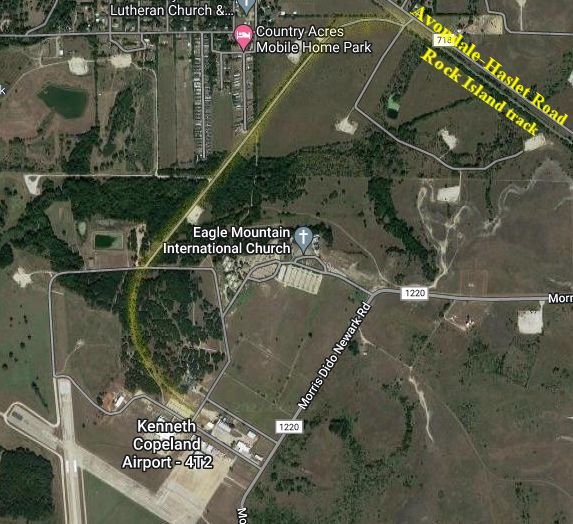

Today the surviving runways are part of private Kenneth Copeland Airport. One original runway has been shortened, another eliminated. Part of the right-of-way of the Rock Island railroad spur (highlighted in yellow) now is a private road that provides access to gas wells.

Copeland built new buildings and renovated others to convert a military base into a ministry headquarters. Now the buildings include a church (see below), Bible college, and studios for producing and broadcasting radio and television programs and for recording audiovisual media. The compound also has warehouse and distribution facilities for merchandise (Bibles and other books, T-shirts, mugs, posters, CDs, DVDs, even adhesive bandages for children).

A new hangar was built on the site of the 1942 original. As of 2019 Copeland’s ministry owned three private jets, including a $20 million Citation X and a Gulfstream V, which costs from $16 million (previously owned) to $62 million (with that “new jet smell”).

On the aerial photo the blue circle is the seaplane ramp and apron with taxiway connecting to the shortened runway. The yellow circle shows the $6 million, 18,000-square-foot Copeland parsonage. (Photo from Wikimapia.)

Semper Fi.

Poly High’s Crooning Fullback

Kenneth Max Copeland was born in Lubbock in 1936.

By 1950 his family was living in Abilene. In the 1950 census father Aubrey Wayne was listed as the registrar of a business college. Mother Vinita was listed as a “naturopath doctor” (WebMD: “Naturopathic medicine is a system that uses natural remedies to help the body heal itself”).

The Copelands moved to Fort Worth in 1952 in time for son Kenneth to attend three years of Poly High School.

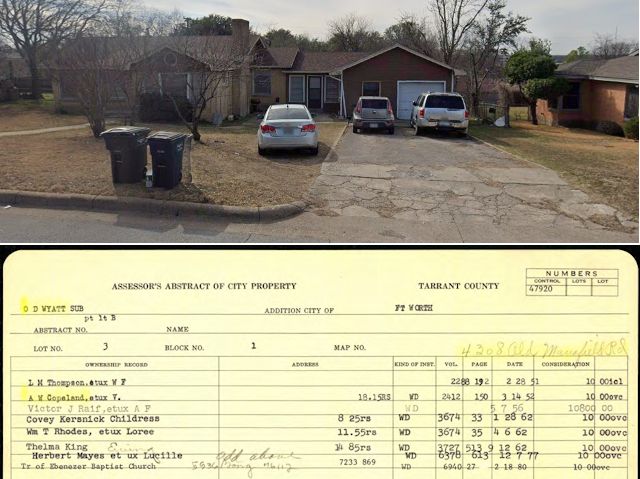

The Copelands lived on Old Mansfield Road in a subdivision developed by Paschal High School principal O. D. Wyatt just west of Glen Garden Country Club.

Kenneth was a twice-gifted teenager: athlete and entertainer.

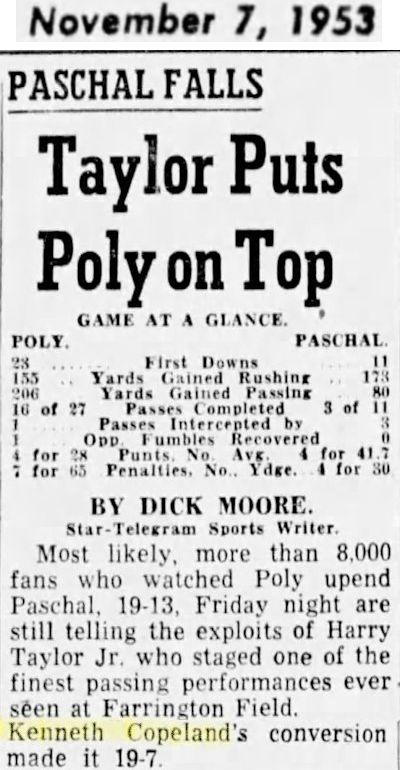

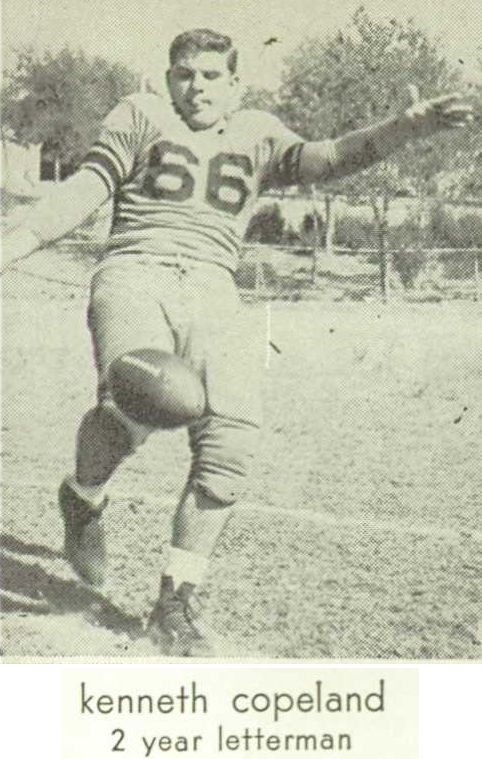

As a junior Copeland played fullback but also was a kicker.

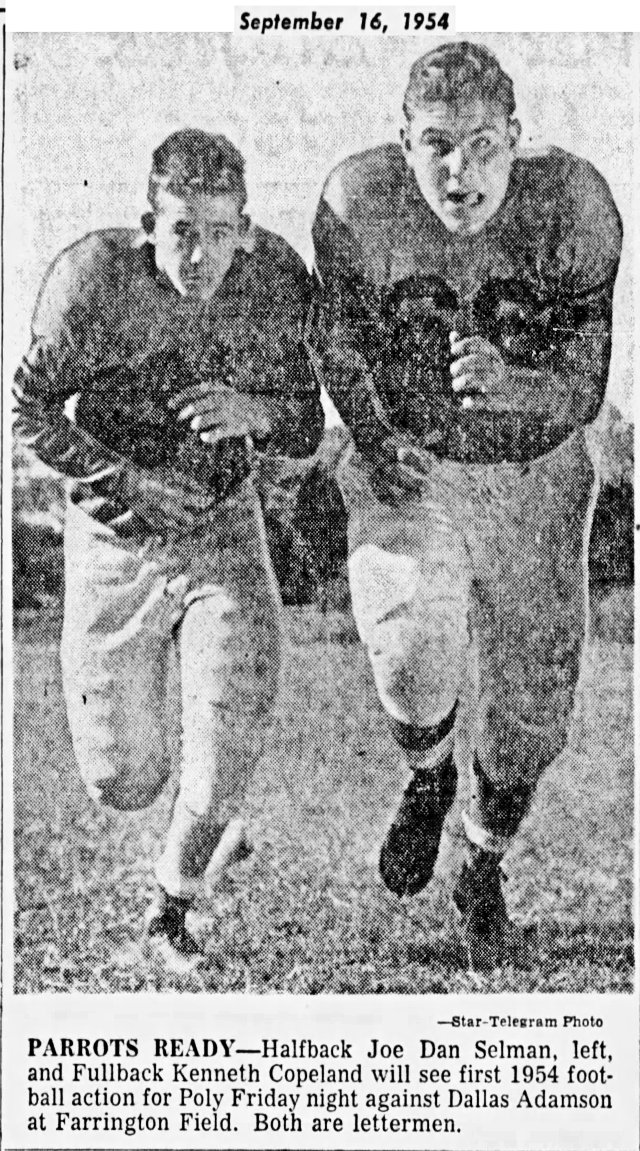

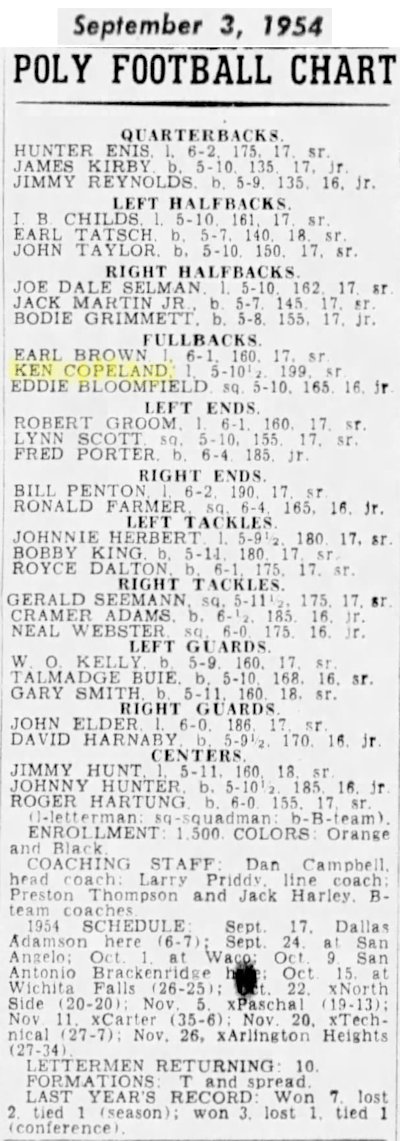

Copeland as his senior year began in September 1954.

At 199 pounds Copeland was the biggest player on the team of quarterback Hunter Enis (later a football star at TCU and in the AFL).

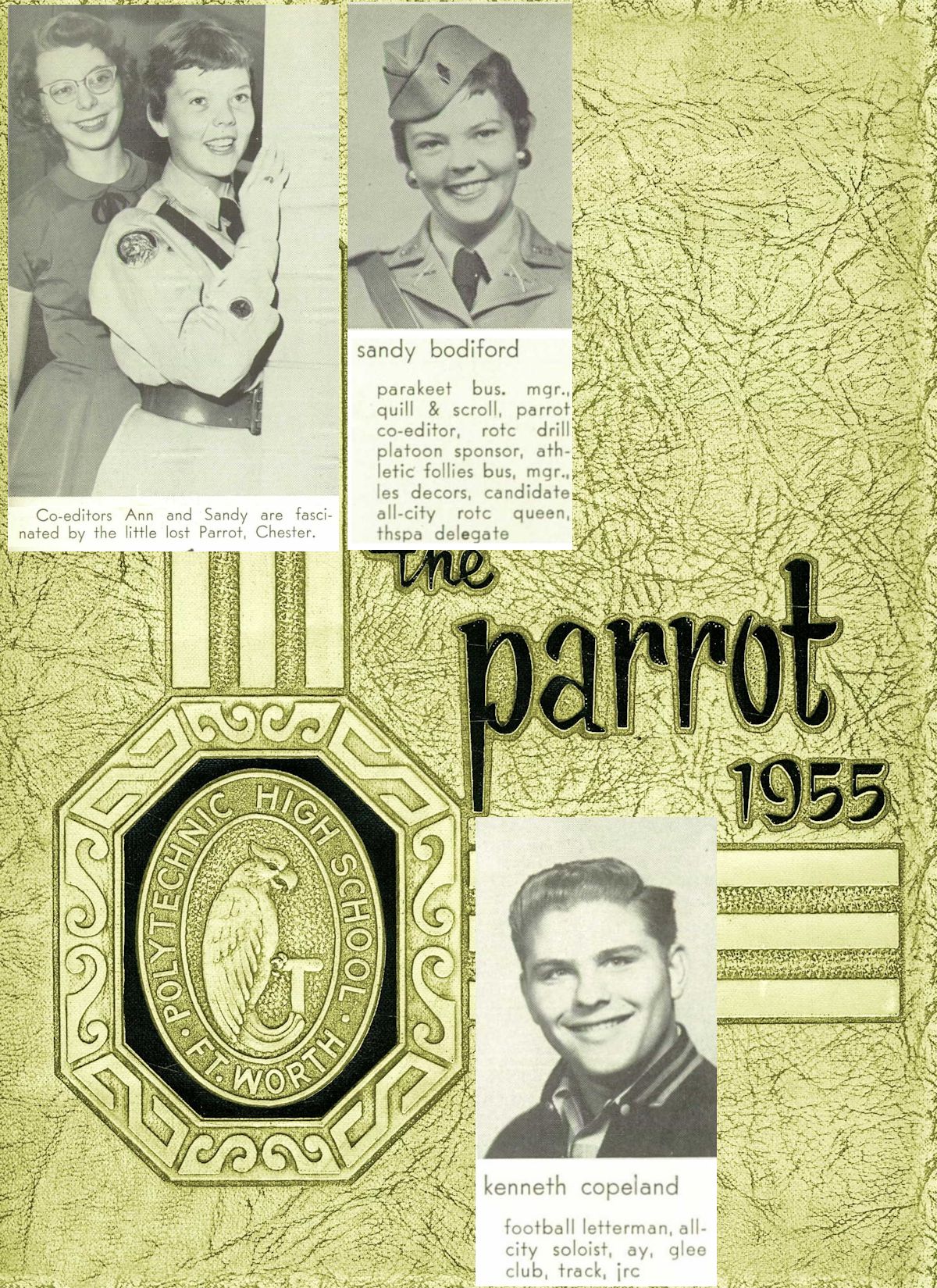

Copeland as a senior in the 1955 Poly yearbook.

The Star-Telegram recognized the young man with one foot on the gridiron and one foot on the stage.

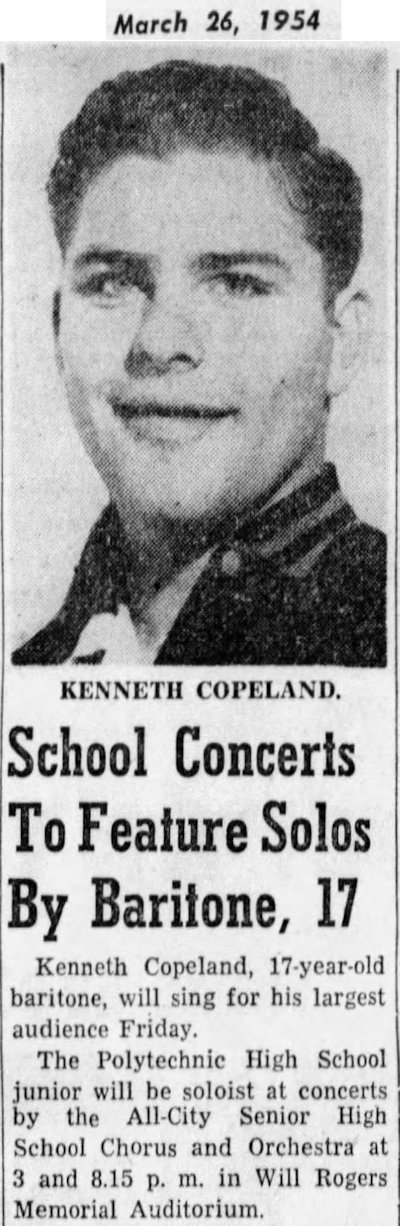

Kenneth Copeland had been singing solos in church since he was twelve years old. As a junior in March 1954 Copeland was soloist in the All City Senior High Chorus and Orchestra.

Copeland also won several singing contests on WBAP-TV’s TV Teen Times pop music program hosted by Pat Boone, who had just begun a recording career and married the daughter of singer Red Foley.

Copeland sang at weddings, even at football banquets. (Poly had won the 4A-3 championship in 1954.)

Copeland graduated from Poly High in 1955.

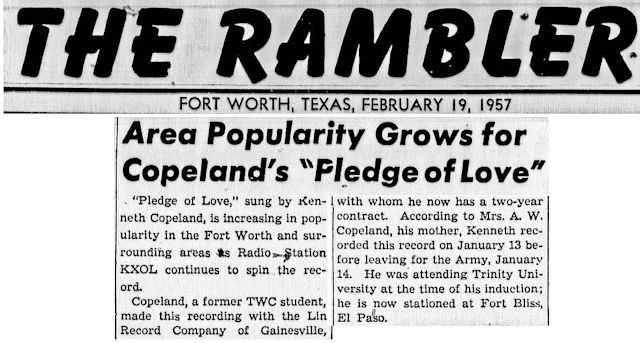

Fast-forward to 1956. Rock and roll had conquered teenagers. Elvis was king. In late 1956 Copeland, with his singing group, the Mints, signed a two-year recording contract with Joe Leonard’s Lin label of Gainesville. In January 1957 Copeland was attending Trinity College in San Antonio when he and the Mints recorded “Busy Body Rock” and “Pledge of Love” (written by Ramona Redd). But that month Copeland also was drafted into the Army.

The day after “Pledge” was released, Copeland left for basic training at Fort Bliss.

“Busy Body” did not sell well, but “Pledge” did. In fact, it sold so well that Leonard turned to larger label Imperial to help churn out 45s.

People who remember Jack Butler as the dignified, white-haired executive editor of the Star-Telegram in the 1970s may have trouble picturing him writing about rock and roll.

Star-Telegram entertainment columnist Elston Brooks also noted the success of “Pledge of Love.”

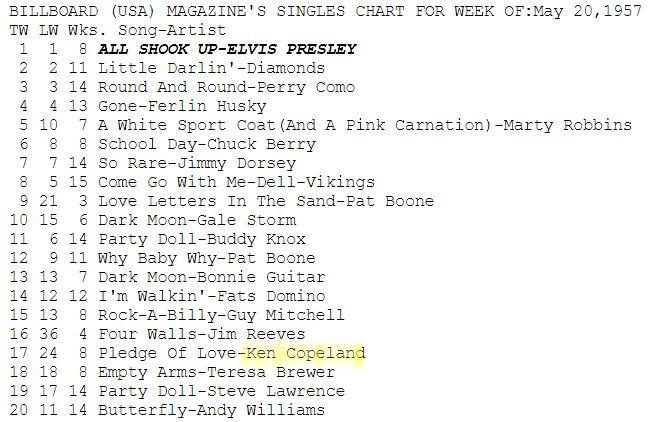

In fact, “Pledge of Love” reached no. 17 on the Billboard weekly chart in May 1957.

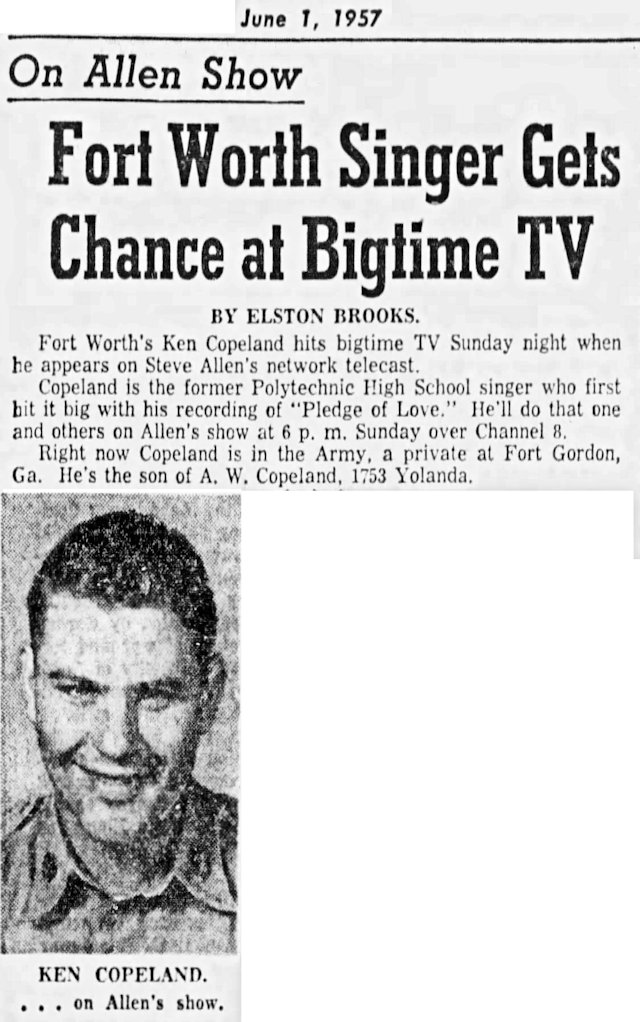

In June, Copeland appeared on the Steve Allen Show.

Copeland recorded a few more singles (“Teenage,” “Someone to Love Me,” “Fanny Brown”) for Lin. In December 1957 he recorded “Where the Rio de Rosa Flows.”

But being in the Army severely restricted Copeland’s ability to help sell the record: public appearances, etc. He was not able to sustain or repeat the success of “Pledge of Love.”

And to whom did Kenneth Copeland make his first pledge of love?

His high school sweetheart was Ivy Sandra Bodiford, daughter of Weldon and Edna Fay Bodiford. Weldon owned Weldon’s Café on Vaughn Boulevard.

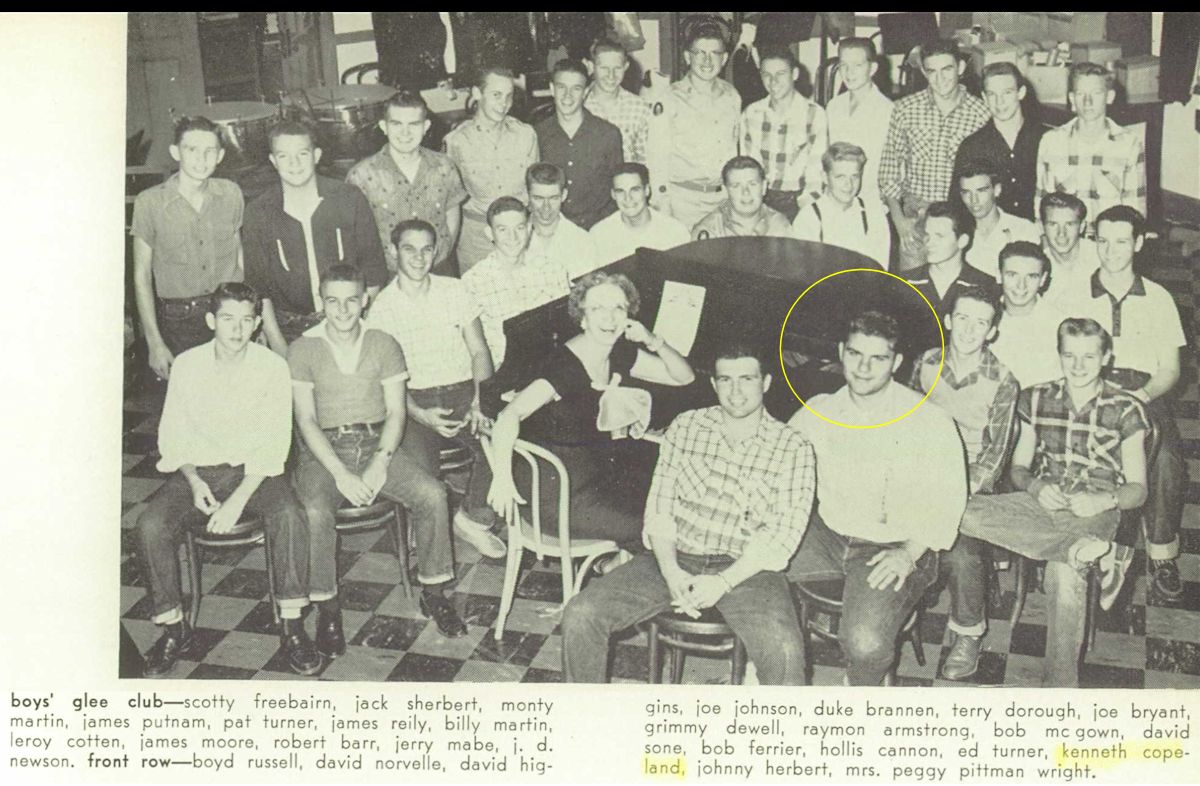

Sandy and Kenneth were a Poly power couple. She was co-editor of Quill & Scroll and the yearbook, business manager of the school newspaper, ROTC drill platoon sponsor, Athletic Follies business manager. He was a football letterman, all-city soloist, and member of Allied Youth, Glee Club, and Junior Red Cross.

Copeland in the Glee Club.

Sandy, like Kenneth, graduated in 1955. Both briefly attended Texas Wesleyan College. They were married in October 1956. They had one child, daughter Terri, born in 1957.

But Kenneth Copeland learned early on that fame brings warts-and-all news coverage. In 1958 Sandy filed for divorce, accusing Copeland of not supporting her and their daughter Terri, then nine months old, and of “stepping out on” Sandy with the woman he would soon marry. Sandy was awarded custody of Terri, and Copeland was ordered to pay child support.

By the time Copeland left the Army his marriage was over, and his promising singing career had lost its momentum. He became a charter airplane pilot, attended Oral Roberts University (where he was chauffeur and pilot for Oral Roberts). In 1968 Copeland formed Kenneth Copeland Ministries in Fort Worth.

And what about Sandy Bodiford, the high school sweetheart who married—and divorced—Copeland in 1958? Fast-forward sixty-four years to 2022. Sandy died at age eighty-five.

Her memorial service was held at Eagle Mountain International Church.

Yes, that’s the church on the Kenneth Copeland Ministries compound at the former military base.

And the church’s senior pastor? Terri Copeland Pearsons—the daughter of Sandy and Kenneth.

More about the Eagle Mountain base

Kenneth has come a long way, my husband said when Poly’s football team traveled by bus, they always had Kenneth sing for them on the trips!