Chances are good that you’ve never heard of Neal Smith Watts. He was never in the news, lived a life of manual labor, died without public mourning. His anonymity is typical of the early settlers in our area, and so is his narrative: He and his family took part in three of the factors that shaped Fort Worth: westward migration, cattle drives, and the railroad.

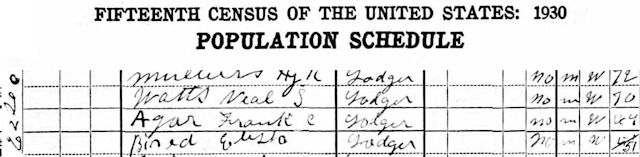

In terms of the time in which he lived, by 1930 Neal Smith Watts was an old man at age seventy. He was a lodger in the Kenneth Hotel, a modest boardinghouse on East 2nd Street.

In terms of the time in which he lived, by 1930 Neal Smith Watts was an old man at age seventy. He was a lodger in the Kenneth Hotel, a modest boardinghouse on East 2nd Street.

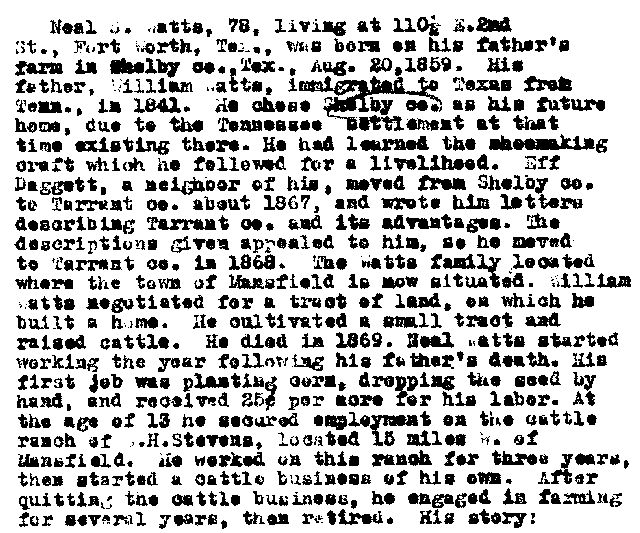

Seven years later, in 1937, Watts was still a boarder at the Kenneth Hotel when he was interviewed by the Federal Writers’ Project, which recorded oral histories in the late 1930s. Above is the transcriptionist’s abstract of his interview with Watts.

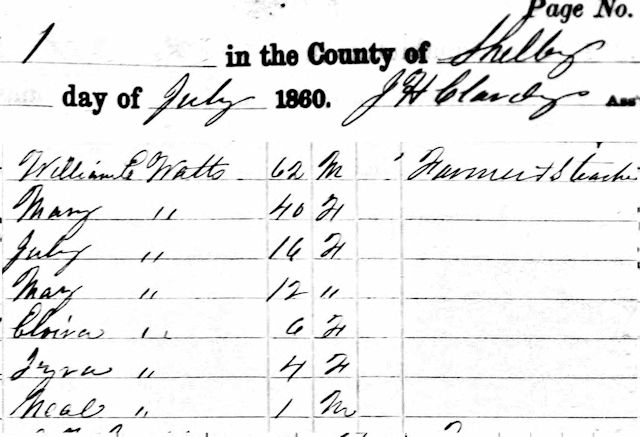

The Watts family was one of the many GTT (gone to Texas) families of the eastern states during the nineteenth century. The Watts family migrated west to Texas from Tennessee in 1841. Neal was born in Shelby County on August 20, 1859. The 1860 Shelby County census listed Neal as one year old, his father as sixty-two.

The Watts family was one of the many GTT (gone to Texas) families of the eastern states during the nineteenth century. The Watts family migrated west to Texas from Tennessee in 1841. Neal was born in Shelby County on August 20, 1859. The 1860 Shelby County census listed Neal as one year old, his father as sixty-two.

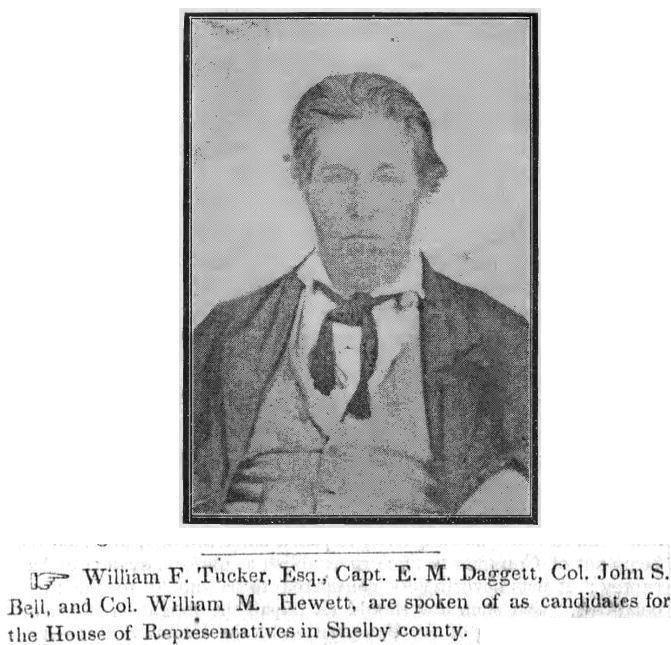

But Neal’s father was encouraged to move his family farther west, to Tarrant County, by a former Shelby County neighbor, Captain Ephraim M. Daggett (1810-1883), who had moved to Fort Worth in 1854. The Texas State Gazette clip shows that Daggett (pictured) was still in Shelby County in 1851. In 1868 the Watts family packed up and resettled near the town of Mansfield in Tarrant County. But Neal’s father died in 1869, forcing Neal to become the man of the house at age ten and to go to work. His first job was planting corn, dropping the seed by hand, for which he was paid twenty-five cents an acre. He planted ten acres a week.

But Neal’s father was encouraged to move his family farther west, to Tarrant County, by a former Shelby County neighbor, Captain Ephraim M. Daggett (1810-1883), who had moved to Fort Worth in 1854. The Texas State Gazette clip shows that Daggett (pictured) was still in Shelby County in 1851. In 1868 the Watts family packed up and resettled near the town of Mansfield in Tarrant County. But Neal’s father died in 1869, forcing Neal to become the man of the house at age ten and to go to work. His first job was planting corn, dropping the seed by hand, for which he was paid twenty-five cents an acre. He planted ten acres a week.

Neal Smith Watts in his own words:

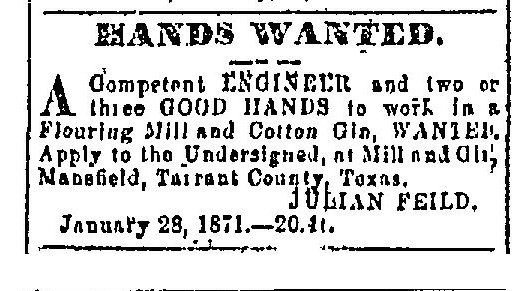

“I did some work for [R. S.] Man and [Julian] Feild, who operated a grist mill on [Walnut] Creek. The town of Mansfield takes its name from these two men. . . .”

“After the mill was built a community began to develop. A store and blacksmith shop were the first to be located, then gradually others, and finally a post office was located there. I have a vivid mental picture of the first church building because it was built of logs, the work being done by the men of the community with my assistance. There was not a nail used in the structure. All timbers were fastened in place with wooden pegs. Nails cost money, and the nails were donated, consequently we used our labor to make wooden pegs and saved spending money for nails.”

“After the mill was built a community began to develop. A store and blacksmith shop were the first to be located, then gradually others, and finally a post office was located there. I have a vivid mental picture of the first church building because it was built of logs, the work being done by the men of the community with my assistance. There was not a nail used in the structure. All timbers were fastened in place with wooden pegs. Nails cost money, and the nails were donated, consequently we used our labor to make wooden pegs and saved spending money for nails.”

When Watts was thirteen he went to work as a cowboy on the ranch of L. H. Stevens. Watts’s pay was $15 a month. He recalled a typical cattle drive:

“Before dusk, the cattle would start to bed, and by dark, as a rule, the entire herd would be bedded down. In ordinary clement weather four night riders kept watch over the herd. The night riding was done by groups of four working in four-hour shifts. During the ’70s there were many depredators, such as cattle rustlers and Indians in some sections along the trail’s route, and it was necessary to guard against the depredations. The depredators would stampede the cattle to produce strays, which they would pick up. . . .

“We drove the cattle through Fort Worth and crossed the Trinity River about a mile northeast of where the courthouse is now located. At this point was the best place for fording the river with the cattle. Our route out of Fort Worth was northwest to Wilbarger County to what was called ‘Doan’s Crossing’ on the Red River. At Doan’s Crossing we forded the Red River. From this crossing we drove northward to Kansas City.

“We forded many streams. Some were crossed easily, while others presented more or less difficulties. Our troubles fording streams were due to high water which we occasionally encountered following rains. By the time we arrived in the Indian Territory and farther west, the cattle had learned to take the water readily, but when the water was high it was also running swiftly. With a swift-running stream the tendency of the cattle is to drift down the stream with the current. Under such a condition, it was necessary for the riders to swim their hosses at the lower side of the herd and, by waving slickers or the curled lassos, force the cattle to swim against the current enough to remain in a straight course. At times the riders were unable to accomplish their purpose, and cattle would reach the opposite bank scattered down the shore. Perhaps some of the cattle would get into bogs of quicksand, and then we would have a time pulling the critters out.

“After we arrived at the end of our drive and the cattle were disposed of, we relaxed for three days before commencing our return trip. There were plenty of amusement places of various kinds, and the boys enjoyed themselves according to their taste. Some of the boys felt worse after three days of the rest period than when they began the relaxation, but all felt they had a good time.”

When Neal was sixteen he started a cattle ranch of his own near Mansfield. But he soon needed cash:

“Just about the time I had my fence underway and was wondering where I could get some money to complete the job, the Texas and Pacific railroad built into Fort Worth, which was in 1876. The track building had reached where Arlington is now, and the builders were pressed for time to complete the road into Fort Worth on a specific date so that they could received a bonus. The contractors needed all the workers they could possibly crowd on the job. I went to work for Hughes, a team contractor, and drove a team of mules pulling a scraper. I started to work when the grading work was going on at about where the west edge of Arlington is now and continued until the track was laid to the depot of Fort Worth. At the time, the depot was located on a tract of land south of Lancaster Avenue and east of Main Street.

“I don’t suppose there has been another piece of track laid which will compare with the original T&P track from Arlington to Fort Worth. I worked cutting down high spots and filling the low places. For a high spot to receive attention it had to be an abrupt rise, and the low places received the same attention. What we actually did was to level the ground so that each end of the ties would be on a level. When we came to a creek which required a bridge, instead of building a trestle we placed a crib of ties on which the track was laid. When we reached the ground near where the depot was located, there a duck pond was encountered, which had been used by the farmer owner raising geese and ducks. It would require some time to fill the pond, therefore the track was laid curving around the pond and back to the depot.

“Towards the last week or so, men and teams worked ’til exhausted, then would rest a short time and return to the job. Just so fast as a way was provided for laying ties and rails, they were laid.

“There was some provision in the Legislature’s grant which set out that the road must be completed on or before the Legislature adjourned. The Legislature’s time to adjourn was three or four weeks prior to the time the road was completed into Fort Worth, but by some parliamentary maneuver the friends of Fort Worth were preventing adjournment. It was by a close margin that the Legislature was held in session. Each day rumors went the rounds to the effect that Fort Worth would lose the Legislature battle, followed by a contrary report. Such rumors continued up to the day the track was laid to the depot.

“The day the first train came into town, which was the final act in winning the race against time, was a day of celebration in Fort Worth for everybody. People came into Fort Worth for miles around, some driving hosses or mules hitched to buggies or wagons, some driving ox teams hitched to carts or wagons, and many on hossback. The largest contingency was cowboys riding mustangs. Many of the visitors had not seen a railway train before, and I was one of them, except for the work train which hauled material on the laid track behind us workers.

“The people began to gather early in the morning of July 19th, 1876, which was the day the first train ran over the new road. Folks were craning their necks looking east down the track for the train which was soon to arrive. After considerable waiting, smoke of the engine was soon in the distance, then a shout from the crowd rendered the air. Then the train appeared, wibbling and wabbling, with a slow movement over the track. At times it appeared the train would never reach the depot because the way it swayed a tip seemed certain.”

Clip is from the July 20 Fort Worth Democrat.

“The train finally reached the depot blowing its whistle, then steam began to pop suddenly. The popping of steam scared many of the assembled people, and there was a scurrying to get away. The scared folks soon realized that the engine was not going to burst, and they returned to inspect the locomotive. There were many speeches made foretelling the future of Fort Worth, and, with whistles blowing and bells ringing, the hilarity continued ’til night.”

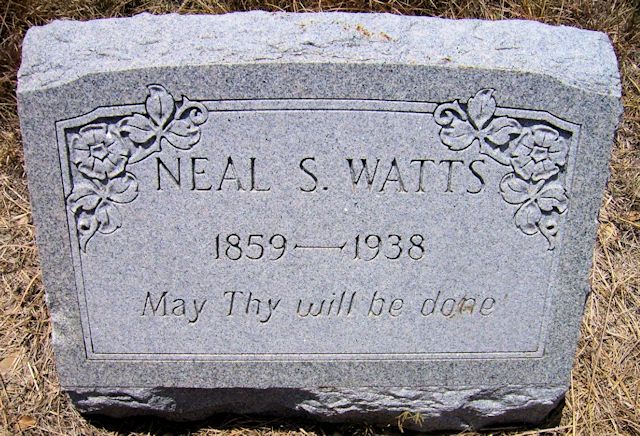

The story of Neal Smith Watts is typical of his contemporaries in one more way: They all lived through a time of tremendous change. When he was born, Fort Worth’s population was less than five hundred. When he died Fort Worth’s population was 175,000. Born before the Civil War, this anonymous working man who rode cattle trails and laid iron rails experienced the closing of the frontier and the opening of our modern age. He lived to see the first transcontinental telegraph line, the telephone, indoor plumbing, the automobile, the airplane, radio, motion pictures, penicillin, refrigeration, air-conditioning, a first world war, and the antecedents of a second world war.

He died on the day after Christmas in 1938, the year Howard Hughes flew a Lockheed Super Electra around the world in a record three days, nineteen hours; the locomotive Mallard set a world speed record for steam by reaching 126 miles per hour; and ballpoint pens, Teflon, and nylon were introduced.

Neal Smith Watts is buried in Coryell County.

Neal Smith Watts is buried in Coryell County.

I’m sorry I doubted you! Wondering how “Feild” became part of “Mansfield,” I went to Wikipedia. Well, if you are wrong, so are they. And I learned about the “Confederate Tithe” as well, which was new to me. I suppose the change from Feild to field makes sense as well.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mansfield,_Texas

His last name is perhaps the most commonly misspelled in local lore. And with good reason. When it’s right it looks wrong. It is correct on most plaques and historical markers but appears as FIELD in a lot of old newspapers. And you see both MAN and MANN for his partner.