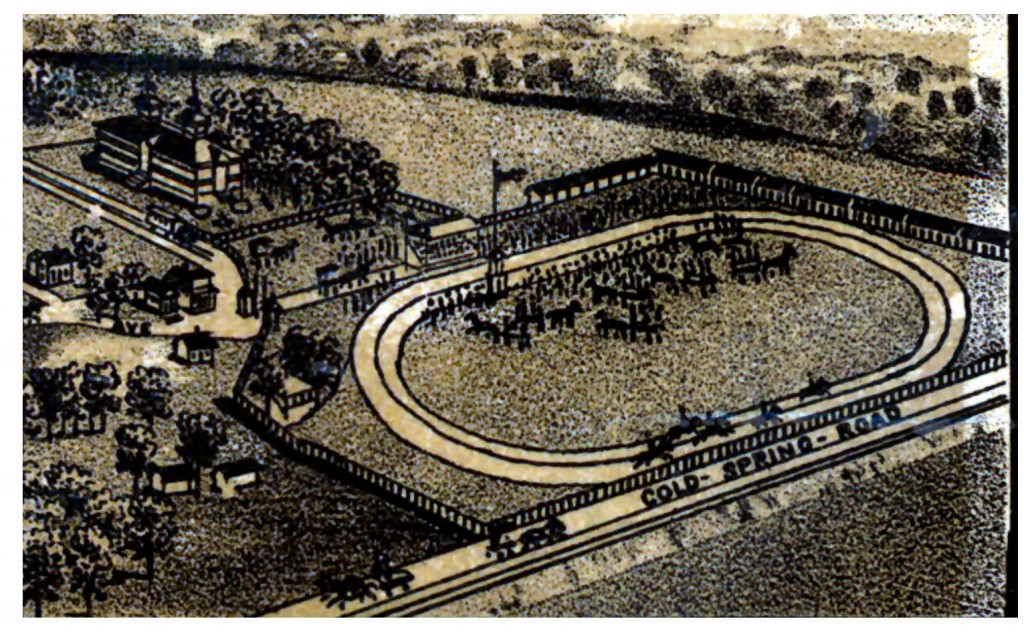

In the Samuels Avenue neighborhood (see Part 1), the new driving park (see Part 2) opened in 1883 on Cold Springs Road.

The oval racetrack can be seen in this detail of an 1886 bird’s-eye-view map.

The oval racetrack can be seen in this detail of an 1886 bird’s-eye-view map.

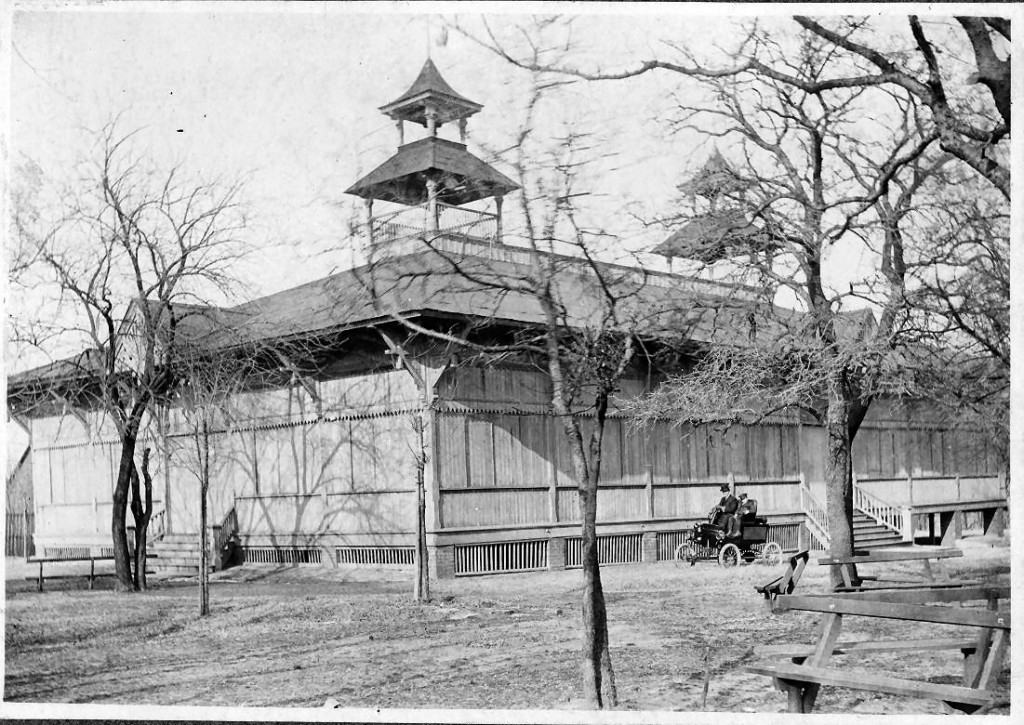

Two years later the driving park got a new neighbor: That building with two cupolas northwest of the track was the Rosedale Pavilion.

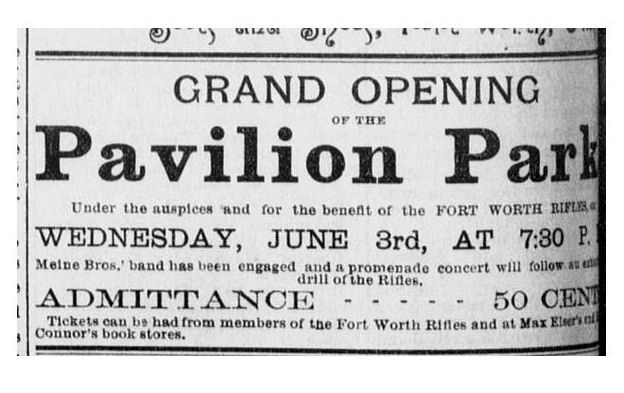

The Rosedale Pavilion opened on June 3, 1885 as “Pavilion Park” with music by the fourteen-piece Meine brothers band, a drill by the Fort Worth Rifles militia unit, and a military ball. Five hundred people attended opening night. Fort Worth’s population was about twenty-two thousand.

The Rosedale Pavilion opened on June 3, 1885 as “Pavilion Park” with music by the fourteen-piece Meine brothers band, a drill by the Fort Worth Rifles militia unit, and a military ball. Five hundred people attended opening night. Fort Worth’s population was about twenty-two thousand.

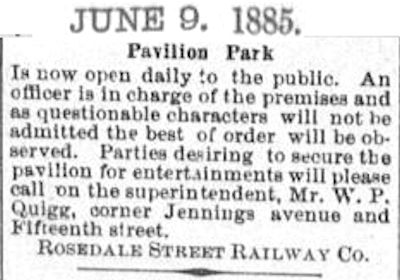

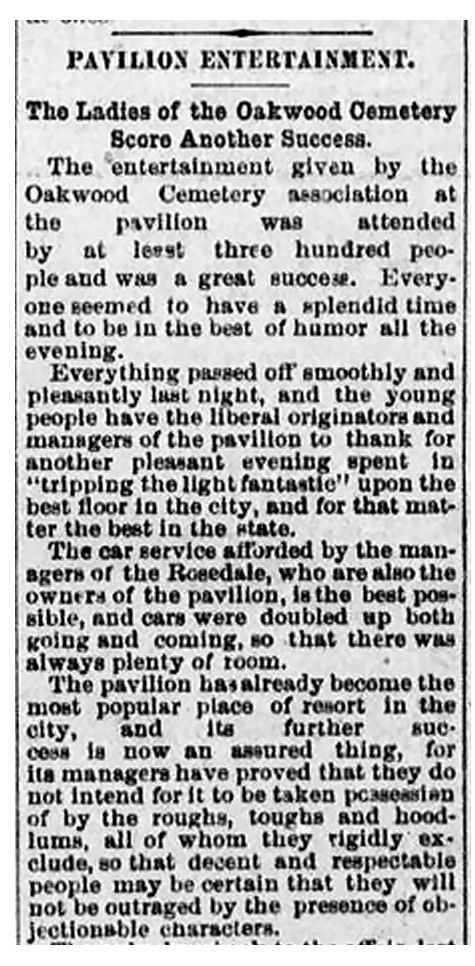

From the beginning the management of the pavilion did not suffer riff-raff gladly. An ad in the Fort Worth Gazette of June 9 assured Pavilion Park merrymakers that “as questionable characters will not be admitted the best of order will be observed.”

From the beginning the management of the pavilion did not suffer riff-raff gladly. An ad in the Fort Worth Gazette of June 9 assured Pavilion Park merrymakers that “as questionable characters will not be admitted the best of order will be observed.”

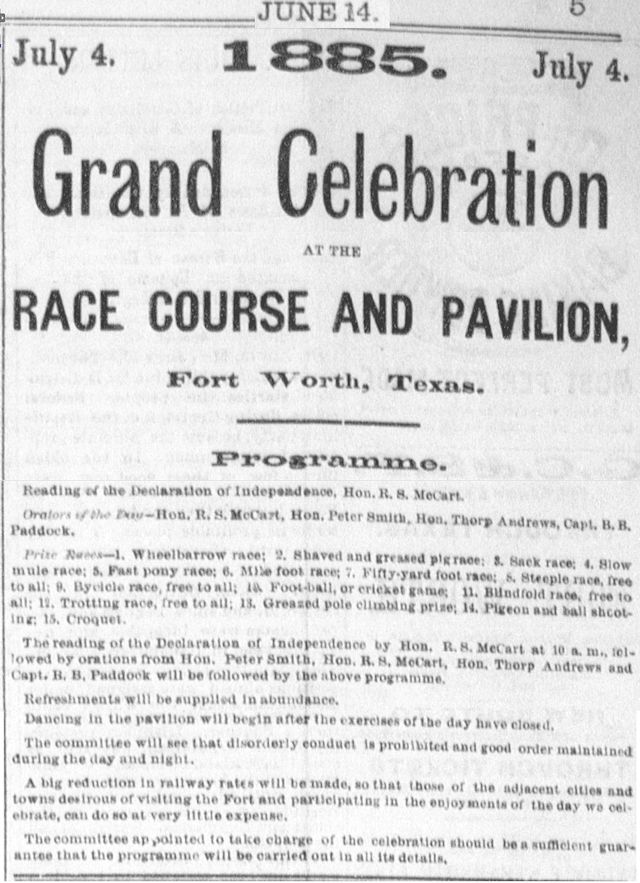

On July 4, 1885 the driving park and pavilion hosted an Independence Day celebration that included a reading of the Declaration of Independence by Robert McCart and orations by John Peter Smith and B. B. Paddock. The merriment included various races, croquet, and dancing. Refreshments were supplied “in abundance.” Again, merrymakers were assured that “disorderly conduct is prohibited and good order maintained.”

On July 4, 1885 the driving park and pavilion hosted an Independence Day celebration that included a reading of the Declaration of Independence by Robert McCart and orations by John Peter Smith and B. B. Paddock. The merriment included various races, croquet, and dancing. Refreshments were supplied “in abundance.” Again, merrymakers were assured that “disorderly conduct is prohibited and good order maintained.”

The pavilion, which measured 60 by 110 feet, was built by the Rosedale streetcar line, which opened in 1884 and ran not along Rosedale Street but rather from the pavilion south to the Missouri Pacific railroad infirmary (the hospital that became St. Joseph) on South Main Street. The bird’s-eye-view map above shows a mule-drawn streetcar on tracks on Pavillion [sic] Street. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

The pavilion, which measured 60 by 110 feet, was built by the Rosedale streetcar line, which opened in 1884 and ran not along Rosedale Street but rather from the pavilion south to the Missouri Pacific railroad infirmary (the hospital that became St. Joseph) on South Main Street. The bird’s-eye-view map above shows a mule-drawn streetcar on tracks on Pavillion [sic] Street. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

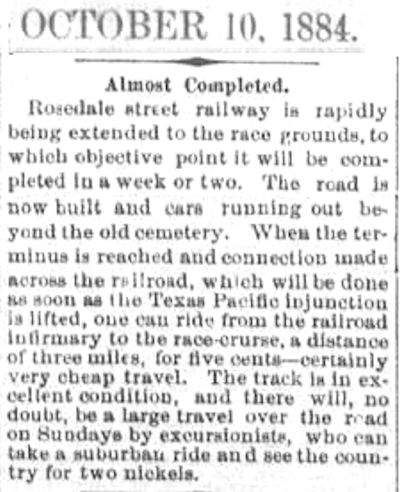

Streetcar companies built trolley parks on streetcar lines to increase ridership. Rosedale Pavilion was the northern terminus of the Rosedale streetcar line. Three other trolley parks were the interurban’s Lake Erie in Handley, Sam Rosen’s White City on the North Side, and Lake Como in Arlington Heights. Note that a round-trip ride was “two nickels.” (The “old cemetery” was Pioneers Rest.)

Streetcar companies built trolley parks on streetcar lines to increase ridership. Rosedale Pavilion was the northern terminus of the Rosedale streetcar line. Three other trolley parks were the interurban’s Lake Erie in Handley, Sam Rosen’s White City on the North Side, and Lake Como in Arlington Heights. Note that a round-trip ride was “two nickels.” (The “old cemetery” was Pioneers Rest.)

Again, this 1885 clip shows that the Rosedale Pavilion’s management didn’t take any guff from “roughs, toughs and hoodlums.”

Again, this 1885 clip shows that the Rosedale Pavilion’s management didn’t take any guff from “roughs, toughs and hoodlums.”

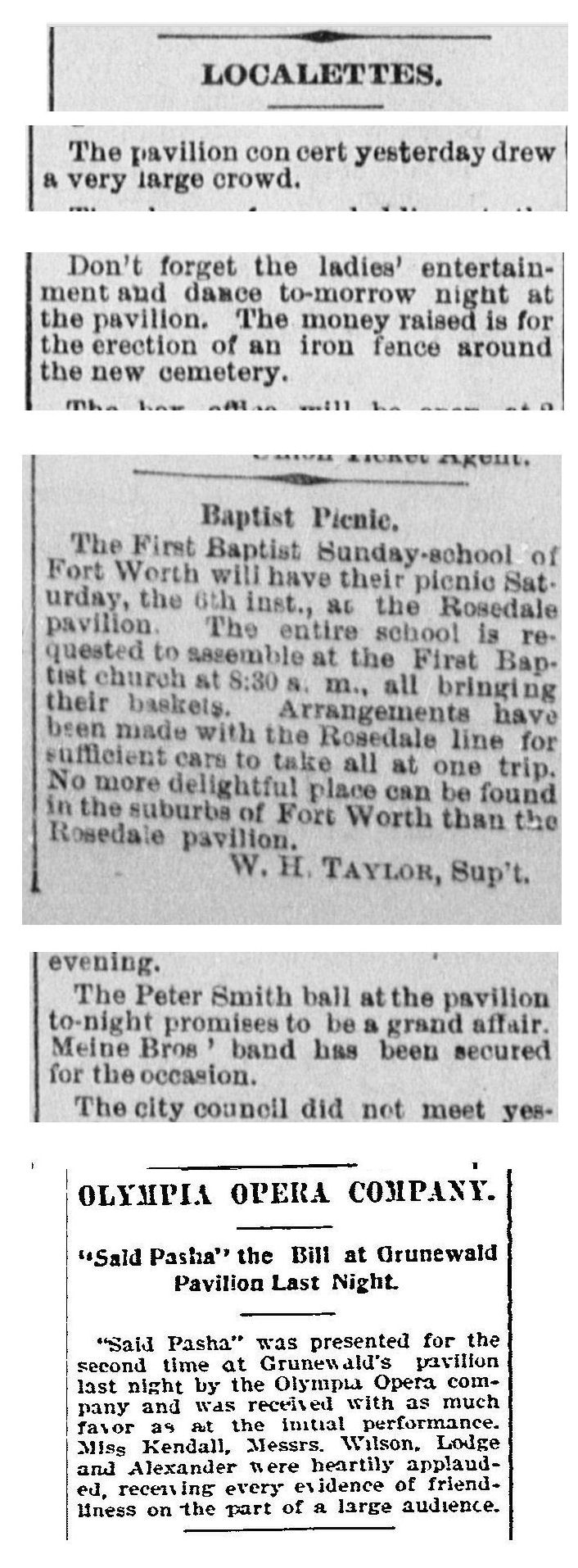

In these clips, the “new cemetery” was Oakwood. The “Baptist Picnic” clip shows the MO of the streetcar companies: Folks such as members of the Sunday school of First Baptist Church paid to ride the streetcars out to the trolley parks, spent money at the trolley parks, and then paid to ride the streetcars back home. The streetcar companies made money going, coming, and in between.

In these clips, the “new cemetery” was Oakwood. The “Baptist Picnic” clip shows the MO of the streetcar companies: Folks such as members of the Sunday school of First Baptist Church paid to ride the streetcars out to the trolley parks, spent money at the trolley parks, and then paid to ride the streetcars back home. The streetcar companies made money going, coming, and in between.

The racetrack closed about 1889, and Peter Grunewald, who operated a hotel/saloon/restaurant on Terry Street, soon became proprietor of the pavilion, which was still outside the city limits. People rode the streetcar out to Grunewald’s Pavilion to drink beer, picnic, dance, listen to music. Grunewald’s Pavilion was also a popular reunion meeting place for Confederate veterans.

The Como Social Club was a local Germanic club formed in 1888. On May 1, 1890 the Comos held Fort Worth’s first Mayfest at the pavilion. Clip is from the Gazette.

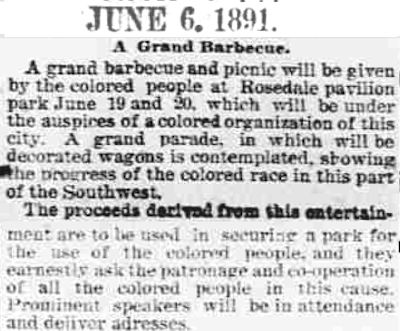

Even after Peter Grunewald bought the pavilion, people referred to it as the “Rosedale Pavilion.” In 1891 Fort Worth’s African-American community was allowed to use the pavilion for a barbecue to raise money for “a park for the use of the colored people.”

Even after Peter Grunewald bought the pavilion, people referred to it as the “Rosedale Pavilion.” In 1891 Fort Worth’s African-American community was allowed to use the pavilion for a barbecue to raise money for “a park for the use of the colored people.”

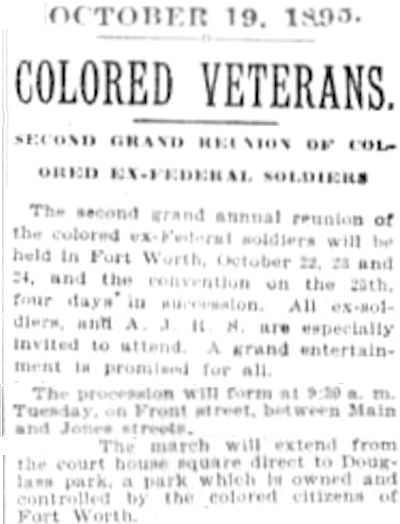

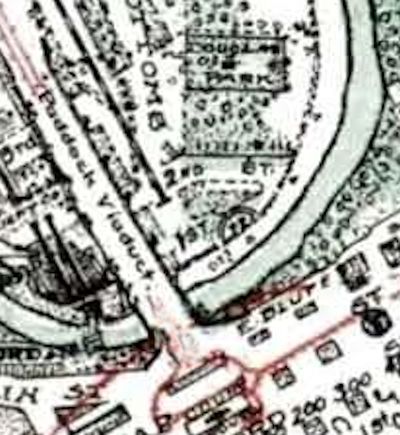

By 1895 Fort Worth’s African-American community had a park (“owned and controlled by the colored citizens of Fort Worth”), even if it was in the flood-prone Trinity River bottoms east of where the Paddock Viaduct would be built in 1914. Douglas Park was named for African-American social reformer and orator Frederick Douglass. (Map detail from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

By 1895 Fort Worth’s African-American community had a park (“owned and controlled by the colored citizens of Fort Worth”), even if it was in the flood-prone Trinity River bottoms east of where the Paddock Viaduct would be built in 1914. Douglas Park was named for African-American social reformer and orator Frederick Douglass. (Map detail from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

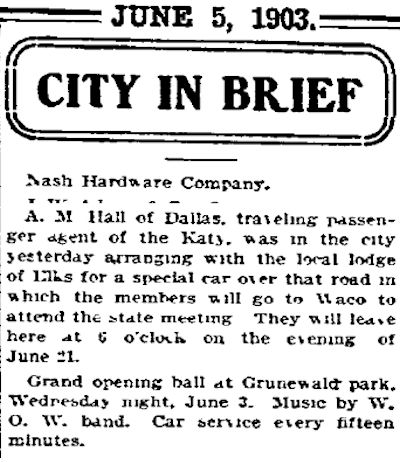

Peter Grunewald did not advertise much in local newspapers, but the grand opening ball of the 1903 season did get into the Fort Worth Telegram’s daily column “City in Brief,” which contained as many ads as news items. The running ad for Nash Hardware Company did not even get a complete sentence. Charles E. Nash probably paid to have his company’s name appear at the top of the column each day.

Peter Grunewald did not advertise much in local newspapers, but the grand opening ball of the 1903 season did get into the Fort Worth Telegram’s daily column “City in Brief,” which contained as many ads as news items. The running ad for Nash Hardware Company did not even get a complete sentence. Charles E. Nash probably paid to have his company’s name appear at the top of the column each day.

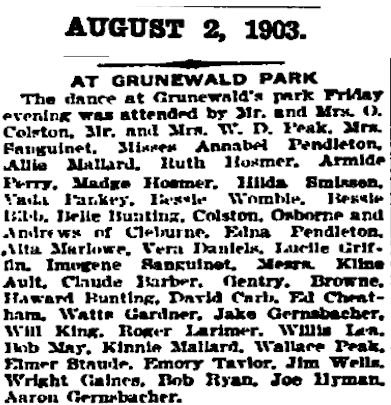

Into the new century people continued to ride “the cars” out to Grunewald Park. Among those attending a party there in 1903 were Mrs. Marshall and Imogene Sanguinet, wife and daughter of the architect; Howard Bunting, who developed Hi Mount, and daughter Belle Bunting, who has a namesake street in Hi Mount; and Howard Wallace Peak, the first white male born in Fort Worth.

Into the new century people continued to ride “the cars” out to Grunewald Park. Among those attending a party there in 1903 were Mrs. Marshall and Imogene Sanguinet, wife and daughter of the architect; Howard Bunting, who developed Hi Mount, and daughter Belle Bunting, who has a namesake street in Hi Mount; and Howard Wallace Peak, the first white male born in Fort Worth.

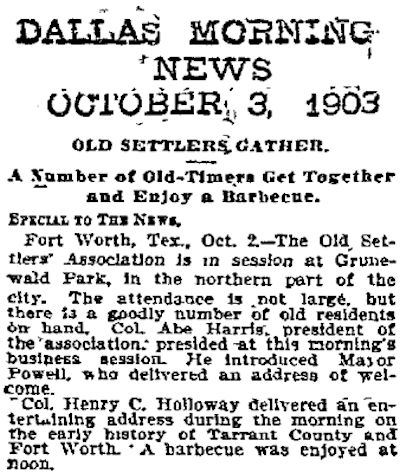

Among those attending a settlers reunion at Grunewald Park in 1903 was Abe Harris, who had been a soldier at the Army’s Fort Worth.

Among those attending a settlers reunion at Grunewald Park in 1903 was Abe Harris, who had been a soldier at the Army’s Fort Worth.

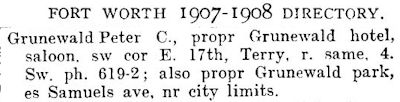

Grunewald Park was still listed in the 1907 city directory.

Grunewald Park was still listed in the 1907 city directory.

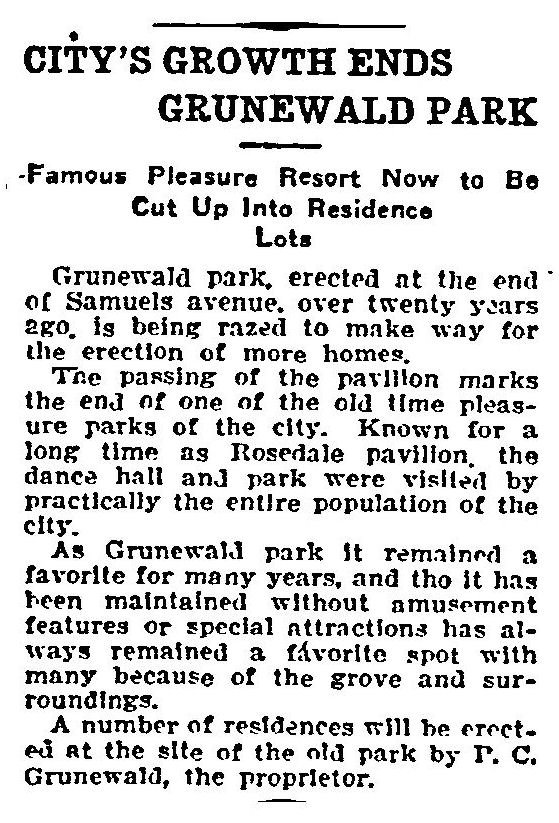

But Peter Grunewald closed the pavilion and park that year. Perhaps a contributing factor was odors from the nearby packing plants after 1902.

But Peter Grunewald closed the pavilion and park that year. Perhaps a contributing factor was odors from the nearby packing plants after 1902.

Grunewald tore down the pavilion but used some of the lumber to build a row of small houses along Pavillion Street, which survives today just south of where the pavilion was.

Grunewald tore down the pavilion but used some of the lumber to build a row of small houses along Pavillion Street, which survives today just south of where the pavilion was.

On Pavillion Street this is one of four surviving houses built with lumber from the 1885 Rosedale Pavilion, Fort Worth’s first trolley park.

On Pavillion Street this is one of four surviving houses built with lumber from the 1885 Rosedale Pavilion, Fort Worth’s first trolley park.

I believe the Rosedale name came from the Rosedale Street Car company that operated a horse/mule drawn streetcar on rails that ran from the Courthouse and terminated at the Rosedale/Grunewald pavilion. (evidence of a streetcar turn-in remains in front of my home in the 800 block of Samuels) Before recent development, a section of brick pavement survived on E. Bluff near the now vanished Cummings street. The center of the brick paved street was raised revealing where the streetcar tracks had been. On the (east) corner of East Bluff and Cummings there was still a rectangular block used as a step-up for the trolley car. (I have a photo of it) I was recently informed that street car/trolley service continued on Samuels until the 1930’s when buses took over that function. Thanks for finding those arcane old newspaper articles that bring a sense of immediacy to the story. I also have a photo of Madam Brown’s “establishment” but it dates from its orphanage incarnation. The city bought the old structure in 1914 and razed it for today’s Ripley Arnold park. This is a great story and I hope someday that someone will take the time to tell the whole story of Samuels Avenue from its origins in 1849 to the present in expanded book form. The neighborhood truly is a mircocosm of our community’s history. My sincerest thanks, Mike, for an outstanding 3-part article.

Do you know the origin of the Rosedale name as it is used in Fort Worth places?

Could only guess. In 1884 a Rosedale subdivision was opened on the South Side. It had these streets with flora names: Rosedale, Violet, Oleander, Magnolia (although, as I understand it, the “Rose” in “Rosedale” comes from “hrossa” meaning “horse”).