In 1856 Fort Worth’s first stagecoach rolled into town. Twenty years later, in July 1876, its first steam locomotive rolled in. And five months after the first locomotive, a mule, whose name is lost to posterity, pulled Fort Worth’s first streetcar down Main Street two days after Christmas: December 27, 1876.

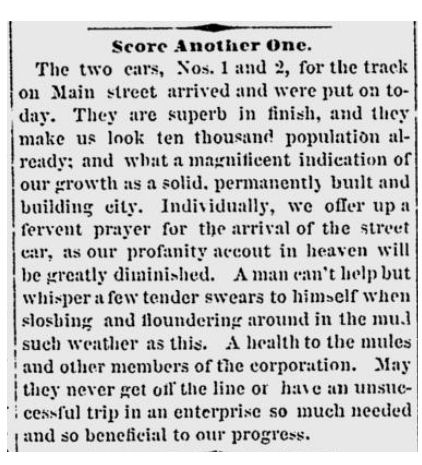

That mule was an employee of Fort Worth Street Railway Company, which had been incorporated with $50,000 capital by, among others, Jesse Zane-Cetti and John Peter Smith. The Daily Fort Worth Standard reported that the first two cars were delivered and placed on the track on December 26.

That mule was an employee of Fort Worth Street Railway Company, which had been incorporated with $50,000 capital by, among others, Jesse Zane-Cetti and John Peter Smith. The Daily Fort Worth Standard reported that the first two cars were delivered and placed on the track on December 26.

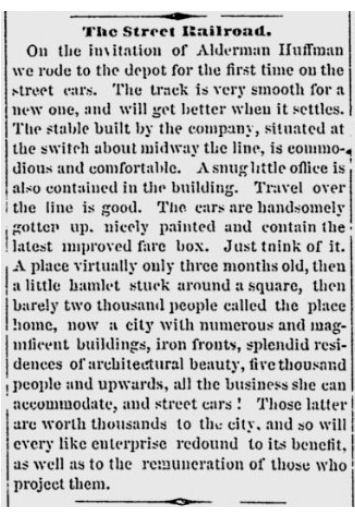

Service began the next day, and a Standard reporter was among the first passengers. Alderman Walter Ament Huffman was secretary of the railway company.

Service began the next day, and a Standard reporter was among the first passengers. Alderman Walter Ament Huffman was secretary of the railway company.

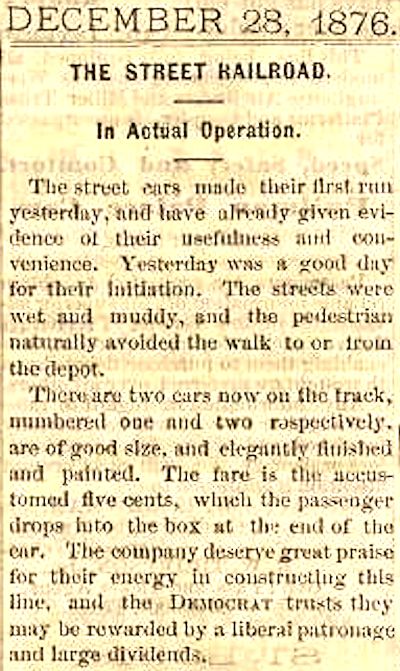

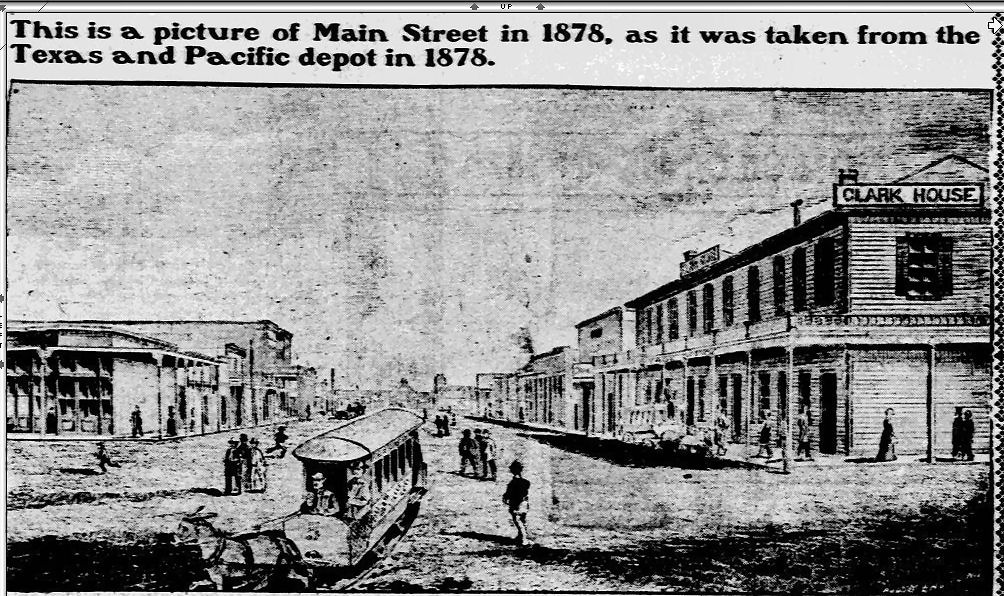

The Democrat also reported on the new service. The track ran the mile from the courthouse south to the Texas & Pacific passenger depot on Main Street, which had been dedicated on September 2. The streetcars were “bobtails”—only about seven feet long with a passenger bench along each side. The fare was a nickel.

The Democrat also reported on the new service. The track ran the mile from the courthouse south to the Texas & Pacific passenger depot on Main Street, which had been dedicated on September 2. The streetcars were “bobtails”—only about seven feet long with a passenger bench along each side. The fare was a nickel.

By 1878 two streetcars were making 160 trips a day, carrying an average of 440 passengers. The company’s annual profit was $7,200.

By 1878 two streetcars were making 160 trips a day, carrying an average of 440 passengers. The company’s annual profit was $7,200.

This 1878 photo printed in the 1903 Telegram shows a mule-drawn streetcar approaching the T&P depot on Main Street at Front Street (Lancaster Avenue today). In 1883 more track was laid downtown.

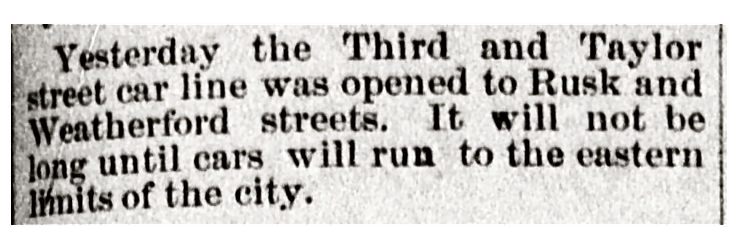

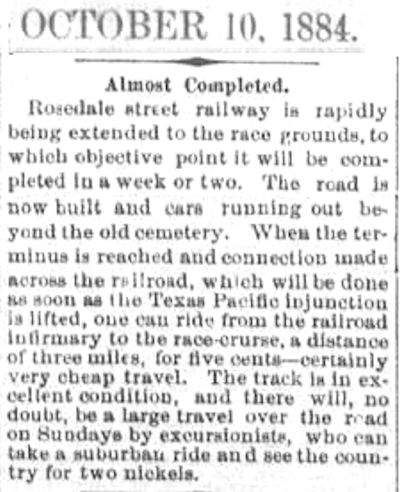

By 1884 Fort Worth Street Railway Company had lost its city monopoly, and the competing Rosedale line began, running from the driving park through downtown to Missouri Pacific Infirmary, the railroad hospital south of town that would become St. Joseph’s Hospital.

By 1884 Fort Worth Street Railway Company had lost its city monopoly, and the competing Rosedale line began, running from the driving park through downtown to Missouri Pacific Infirmary, the railroad hospital south of town that would become St. Joseph’s Hospital.

Businesses capitalized on their nearness to streetcar service.

Businesses capitalized on their nearness to streetcar service.

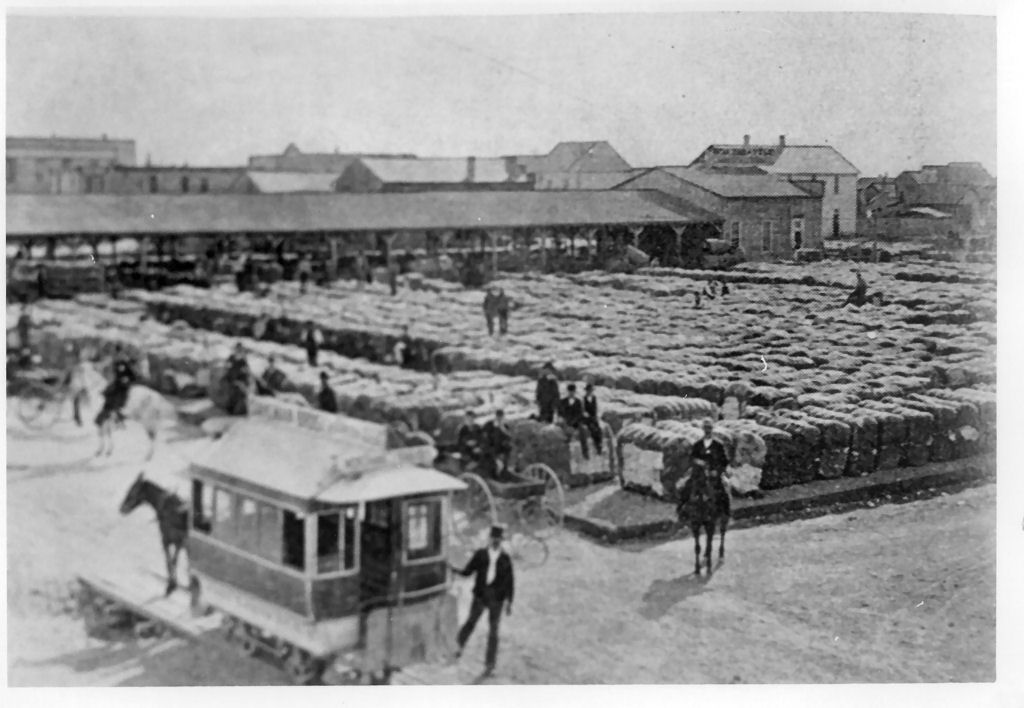

This photo, from about 1880, shows a streetcar at Battle’s Cotton Yard at Main and 14th streets. (Photo from Tarrant County College NE.)

Streetcars were a major advance for Fort Worth: They made moving about town not only faster but also cleaner. City streets were not paved. That meant they were dusty in dry weather, muddy in wet weather.

But streetcars were not without their drawbacks. Sometimes the mule bolted; sometimes the car jumped the track, and passengers had to lift it back onto the rails. Oliver Knight in his Fort Worth: Outpost on the Trinity related the experience of one early passenger: “A bunch of [us] railroad fellows were loafing on our day off when we saw the [street]car. The man that run the car asked if we wanted to ride. Of course, we got on, to our sorrow. About every block the car jumped the track and got stuck in the mud. That’s what he asked us to ride for—so we could lift the darned thing out of the mud.”

Sometimes the derailments had some help.

Sometimes the derailments had some help.

Sometimes two forms of mass transit got crossways with each other. In the early days the conductor of a streetcar preceded his car over a railroad crossing on foot, carrying a red flag during the day and a red lantern at night.

Sometimes two forms of mass transit got crossways with each other. In the early days the conductor of a streetcar preceded his car over a railroad crossing on foot, carrying a red flag during the day and a red lantern at night.

And sometimes there were other hazards, such as passengers with “hoodlumistic propensities.”

And sometimes there were other hazards, such as passengers with “hoodlumistic propensities.”

In 1887, as the city expanded to the west and east, there was even talk of adding streetcar lines that had coaches pulled by small steam engines, but as far as I can tell the city transitioned from mule power to electric—not steam—power in 1889. Among principals in the West Side development proposal were civic leader Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt and attorney/city attorney/land speculator Robert McCart (as in the South Side street name). Among investors in the Sylvania development on the east were gambler Jake Johnson and future disgraced mayor W. S. Pendleton. Clip is from the March 25, 1887 Fort Worth Gazette.

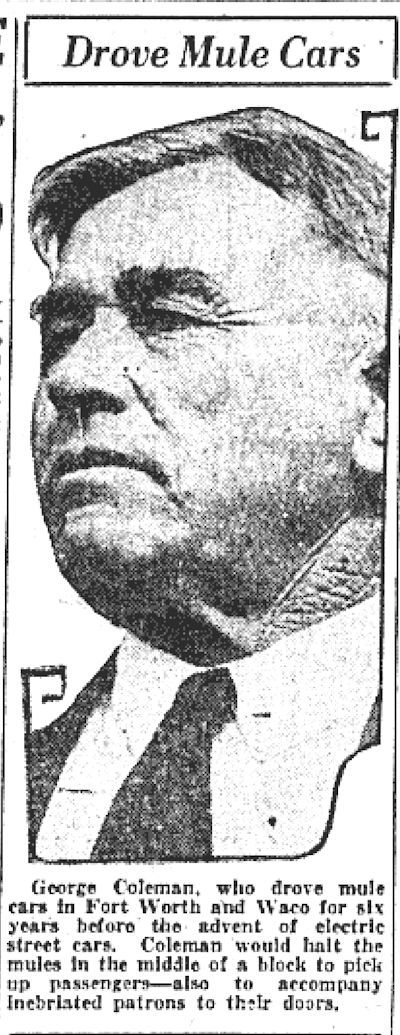

In 1928 George Coleman, who piloted mule-powered streetcars in Fort Worth for two years before beginning thirty-six years on electric streetcars, remembered the early days.

In 1928 George Coleman, who piloted mule-powered streetcars in Fort Worth for two years before beginning thirty-six years on electric streetcars, remembered the early days.

In 1889 he earned $1.50 ($40 today) for a sixteen-hour day.

“Whenever there was an opera or something special on, we had to work overtime, and the company didn’t pay us. The passengers usually would make up a purse for us, and if the driver got half a dollar he considered himself lucky.”

Coleman worked for the Rosedale line. His route began at the Rosedale Pavilion trolley park on north Samuels Avenue, went around the courthouse, south on Houston Street, west over 15th Street to Jennings Avenue, south across the Texas & Pacific tracks on the wooden viaduct to Daggett Avenue, west to Henderson Street, and south again to Terrell Avenue.

If all went well, the trip took about an hour. The mules were changed every third trip by the car barn. Track maintenance consisted largely of filling the holes between the ties gouged by the mules’ hooves.

Coleman remembered how obliging drivers were in the mule-car days. The drivers stopped whenever a pedestrian hailed them, not just at fixed points. Drivers waited outside homes for passengers to finish dressing in the morning, they escorted drunks to their doors at night. Mule cars by then were larger, carrying sixteen to eighteen passengers, although they might carry twice that number (half of whom stood) during rush hour.

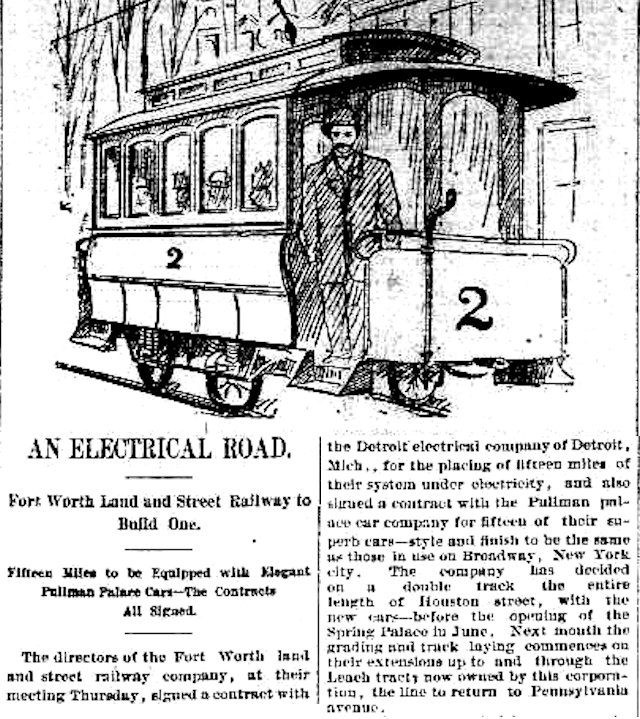

On February 1, 1889 the Fort Worth Land and Street Railway Company announced that fifteen miles of city track would be electrified and new cars purchased. The improvements were to be in place before the Texas Spring Palace exhibition opened. Clip is from the February 1 Gazette.

On February 1, 1889 the Fort Worth Land and Street Railway Company announced that fifteen miles of city track would be electrified and new cars purchased. The improvements were to be in place before the Texas Spring Palace exhibition opened. Clip is from the February 1 Gazette.

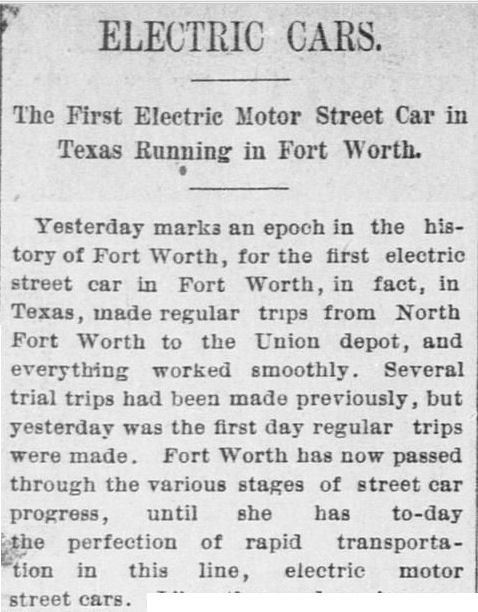

When Fort Worth began electric streetcar service on August 2, 1889, the Gazette claimed that it was a first for Texas.

When Fort Worth began electric streetcar service on August 2, 1889, the Gazette claimed that it was a first for Texas.

On May 18, 1890 the Gazette said the “gay and festive mule” was being retired.

On May 18, 1890 the Gazette said the “gay and festive mule” was being retired.

As electric power replaced mule power, streetcar passengers faced a new hazard: being shocked, especially during wet weather.

As electric power replaced mule power, streetcar passengers faced a new hazard: being shocked, especially during wet weather.

But some old hazards remained.

But some old hazards remained.

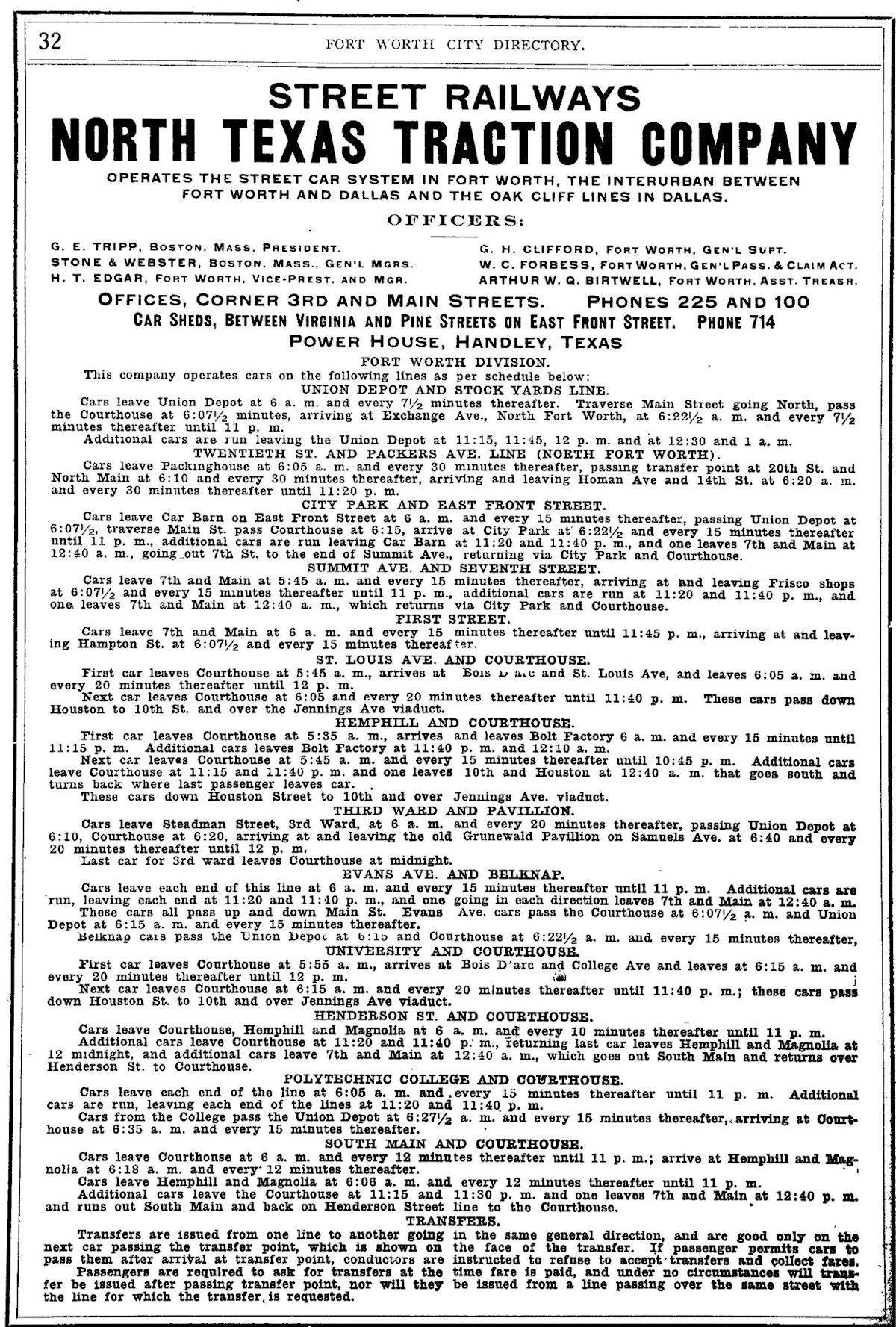

By 1890 more than twenty companies were operating streetcar lines under franchises granted by the city. Fort Worth Street Railway Company bought out several of its competitors until it, in turn, was bought by Northern Texas Traction Company. Northern Texas Traction eventually operated eighty-four miles of streetcar track and in 1902 began the interurban line to Dallas.

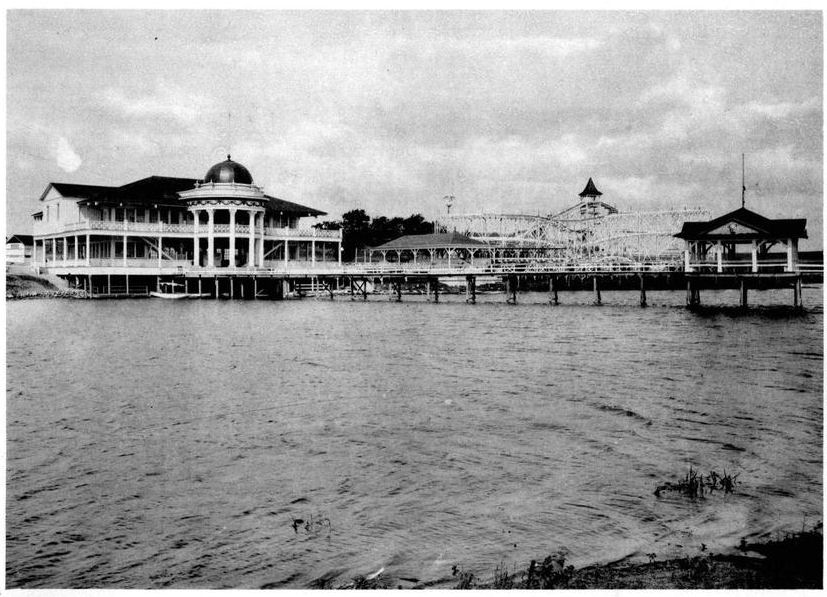

To increase ridership, streetcar companies often built “trolley parks” along or at the end of their line. Fort Worth’s first trolley park was Rosedale Pavilion. Later trolley parks were more ambitious. The Arlington Heights streetcar company built a park at Lake Como (top). On the other side of town, Northern Texas Traction built a park at its generating plant at Lake Erie (bottom) in Handley. And Sam Rosen opened White City for his North Side streetcar company.

To increase ridership, streetcar companies often built “trolley parks” along or at the end of their line. Fort Worth’s first trolley park was Rosedale Pavilion. Later trolley parks were more ambitious. The Arlington Heights streetcar company built a park at Lake Como (top). On the other side of town, Northern Texas Traction built a park at its generating plant at Lake Erie (bottom) in Handley. And Sam Rosen opened White City for his North Side streetcar company.

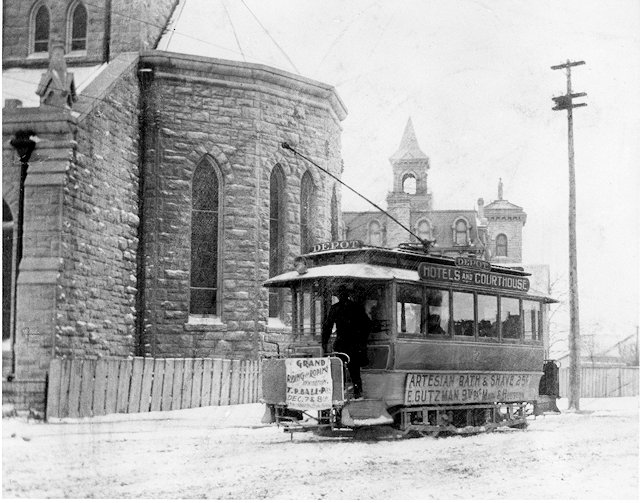

A streetcar passing St. Patrick Cathedral in the twentieth century. Signs on the car advertise E. Gutzman’s barber shop (“Artesian Bath & Shave 25¢”) and a riding and roping exhibition at T&P Park. (Photo from Jack White Photograph Collection, University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

By 1907 Northern Texas Traction Company operated most of the streetcar lines in town. By 1911 NTTC had taken over and consolidated the city’s competing streetcar lines in addition to operating the interurban to Dallas. In 1912 the interurban to Cleburne began operation. In 1923 NTTC added bus service beginning with a route to Riverside. Fare was seven cents with transfers to streetcar lines.

By 1907 Northern Texas Traction Company operated most of the streetcar lines in town. By 1911 NTTC had taken over and consolidated the city’s competing streetcar lines in addition to operating the interurban to Dallas. In 1912 the interurban to Cleburne began operation. In 1923 NTTC added bus service beginning with a route to Riverside. Fare was seven cents with transfers to streetcar lines.

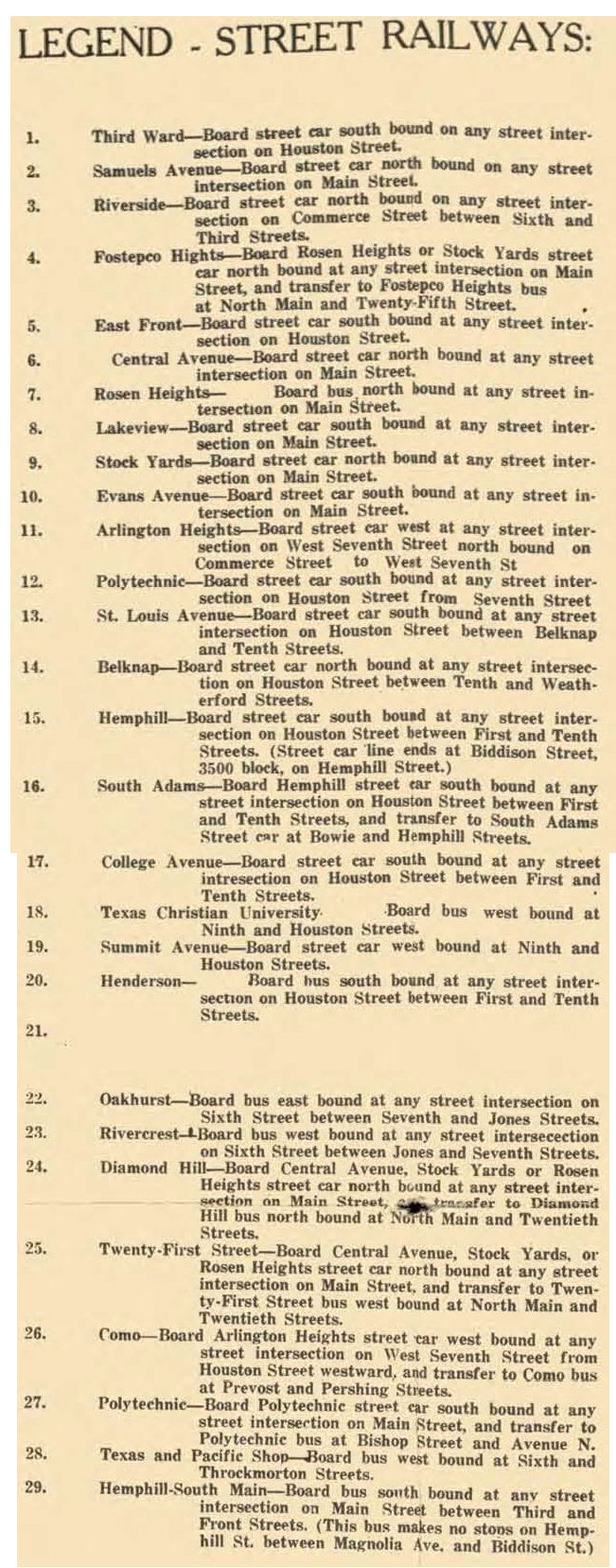

This legend from a city map shows how many streetcar and bus lines there were by 1929. (Map from Pete Charlton’s “The Lost Antique Maps of Texas: Fort Worth & Tarrant County, Volume 2” CD.)

This legend from a city map shows how many streetcar and bus lines there were by 1929. (Map from Pete Charlton’s “The Lost Antique Maps of Texas: Fort Worth & Tarrant County, Volume 2” CD.)

By the 1920s some of Northern Texas Traction’s intracity streetcars were painted in the colors of the schools on their lines. For example, cars that served Texas Christian University were purple and white. Cars that served Central High (today’s Green B. Trimble Tech) also were purple and white. Cars that served Polytechnic High, then on Nashville Avenue, were orange and black. (Photos from North Texas Historic Transportation.)

A Northern Texas Traction Company streetcar, 1925. (Photo from Hagley Digital Archives.)

A Northern Texas Traction Company streetcar, 1925. (Photo from Hagley Digital Archives.)

By 1929 NTTC also was operating Texas Motorcoaches buses between Fort Worth and Dallas, competing with its own interurban rail service.

By 1929 NTTC also was operating Texas Motorcoaches buses between Fort Worth and Dallas, competing with its own interurban rail service.

In 1931 NTTC ended interurban service to Cleburne. The next year the company went into receivership. The interurban to Dallas was discontinued in 1934.

NTTC was reorganized and emerged in 1938 as “Fort Worth Transit Company.”

NTTC was reorganized and emerged in 1938 as “Fort Worth Transit Company.”

In 1938 the Light Crust Doughboys were on the air, and Fort Worth Transit Company buses were on the street. By 1949 the bus system had 245 buses on 177 miles of street carrying 116,000 passengers a day.

In 1938 the Light Crust Doughboys were on the air, and Fort Worth Transit Company buses were on the street. By 1949 the bus system had 245 buses on 177 miles of street carrying 116,000 passengers a day.

(Watch a 1930s silent documentary on the Thurber brick plant. A streetcar on Fort Worth’s North Main Street is shown at the time remaining of -:52.)

The next year Fort Worth Transit Company discontinued streetcar service. Among passengers on the last trolley were a man who had driven one of the mule-drawn cars and two persons had ridden on the first electric car in 1889.

The next year Fort Worth Transit Company discontinued streetcar service. Among passengers on the last trolley were a man who had driven one of the mule-drawn cars and two persons had ridden on the first electric car in 1889.

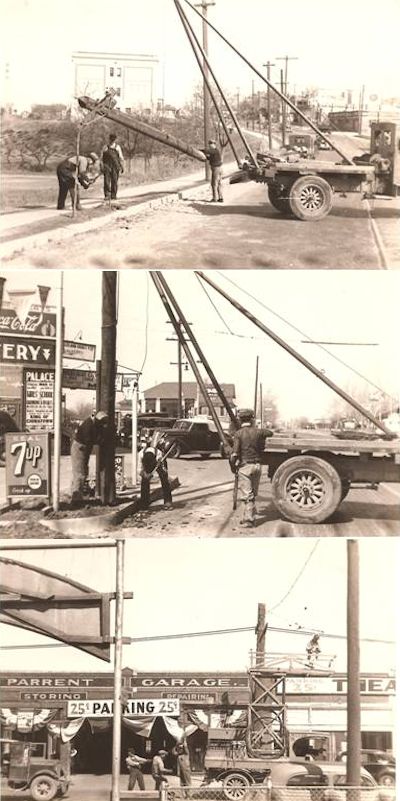

Hundreds of streetcar poles and miles of streetcar track and wires were removed in 1939. Dozens of streetcars were sold and repurposed as diners, storage buildings, additions to houses. The top photo shows a pole being removed on East Vickery Boulevard. R. Vickery School is in the upper left. A track can be seen in the middle of the street. The bottom photo shows Parrent parking garage on Commerce Street opposite the Majestic Theater. (Photos from Barbara Love Logan.)

Hundreds of streetcar poles and miles of streetcar track and wires were removed in 1939. Dozens of streetcars were sold and repurposed as diners, storage buildings, additions to houses. The top photo shows a pole being removed on East Vickery Boulevard. R. Vickery School is in the upper left. A track can be seen in the middle of the street. The bottom photo shows Parrent parking garage on Commerce Street opposite the Majestic Theater. (Photos from Barbara Love Logan.)

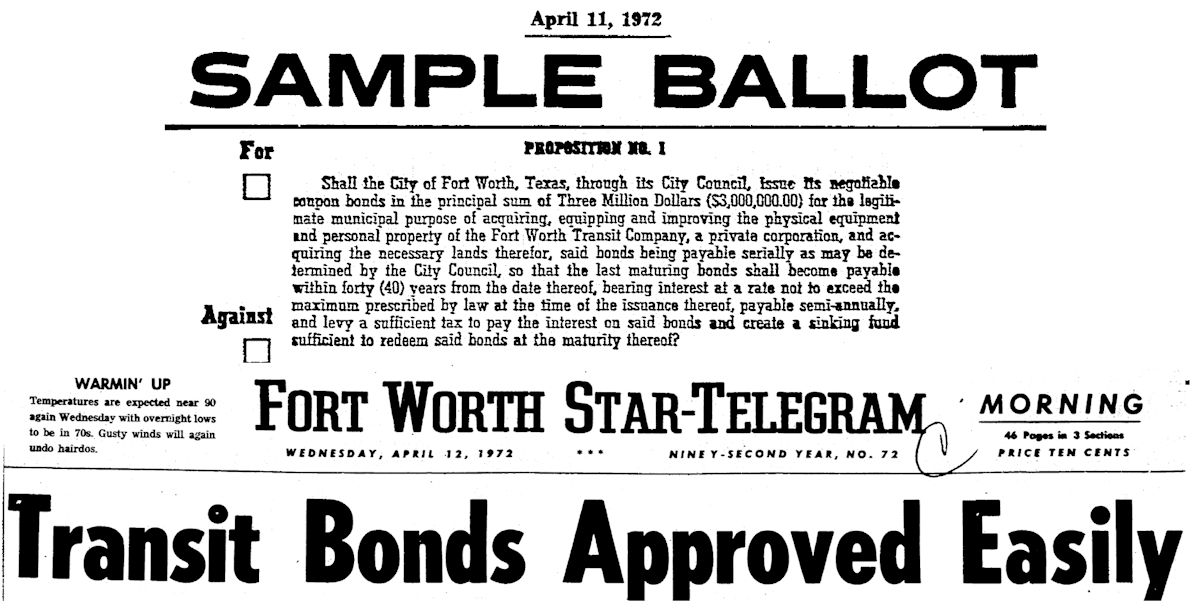

But in 1972 voters approved bonds to allow the city to buy Fort Worth Transit Company and operate its bus system. After seventy years the company that had started the interurban in 1902 had reached the end of the line. Everybody off.

But in 1972 voters approved bonds to allow the city to buy Fort Worth Transit Company and operate its bus system. After seventy years the company that had started the interurban in 1902 had reached the end of the line. Everybody off.

And it all began one Christmas with a mule.

I just discovered this article; I realize it is old. But lived for ten years next to a farm owned by an elderly farmer. When he passed away a few years ago, and the building behind our house was cleared away; it turned out to be an old interban car at it’s core. It was so covered with sheet metal and other material I lived next to it for a decade and never realized it.

https://www.facebook.com/james.hefner.73/posts/10220331776039027

Thanks, James. That scenario was played out thousands of times. Cars were scrapped, repurposed, disguised, neglected. Too bad more of them were not preserved.

Oh, by gosh, by golly

It’s time for mistletoe and trolley…

Merry Christmas and happy railroading in the new year, Dennis.

How much are the Northern Texas Tract Co Ft Worth 1920 tokens worth?

I bought mine on eBay but don’t remember the cost. Not much, I am sure. This website might help.

An older friend of mine said that when his parents moved to Odessa they lived in a cast-off streetcar from Ft. Worth. Housing was so scarce in the Permian Basin back in the 1940s that several were relocated there as houses.

Today there is a streetcar body on the north side of I-20 between Ft. Worth and Abilene. Probably a former Ft. Worth one.

It was just a huge amount of rollingstock and infrastructure to remove and get rid of. Fort Worth still uncovers remnants of track during street projects. I hate to think of what became of most of those cars. I was hovering over the north Fort Worth area on satellite maps while doing some research when I noticed something interesting in a backyard. A narrow rectangle with gently rounded ends. Street view revealed nothing but a privacy fence. I went out to the property. You can’t see over the fence from the street. But I peeked over the fence. The rectangle was the roof of a streetcar! Checking the address, I found that the property belongs to a guy involved in streetcar preservation.

My grandfather was a motor man for Sam Rosen’s line I believe. I have a picture of him and the conductor on his car. He related a story about stepping off the car from the front door of the car (while it was in motion) and hooking his arm around the rail of the rear door as it passed to climb back into the car.

This apparently caused some discomfiture amongst some of the riding passengers.

Except for a few relics like your photo, it’s as if the era of the streetcar never happened. I imagine that jobs on the cars carried some prestige-men got to wear a uniform, command authority among passengers, see the world (or at least the town).

Do you have a Cleburne interurban map? I’m trying to find if it ran on Wilhite Street. Maybe our Streetcars ran on Wilhite, but I have not found proof. Thanks.

I do not. The Sanborn fire maps, which normally were so detailed, show only the interurban waiting room on Caddo in the Wright Building. The Sanborn maps show only railroad tracks, not interurban tracks, in Cleburne. I have not found a detailed old Cleburne city map at General Land Office or Library of Congress. Separate post on Cleburne line.

Headlines: Transit pole electrifies voters.

Expanding streetcar system gains traction.

TCT Co. demands fare play.

Wouldn’t touch those lines with a ten-foot rail!

Excellent local history.

Thanks, Tommie. I love streetcar history.