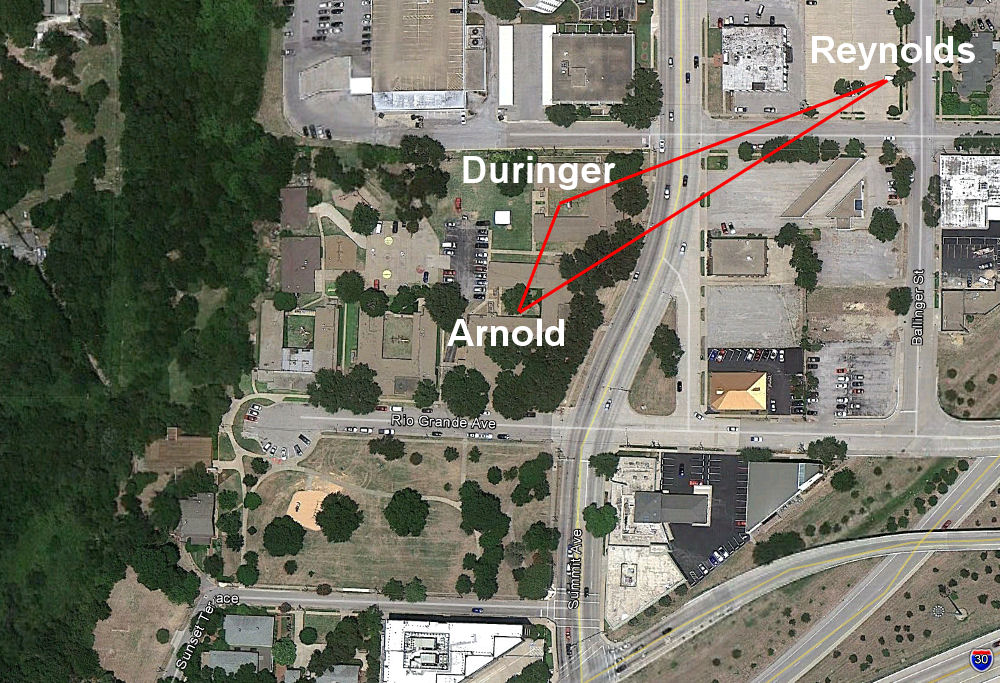

We could call it the “Iron Triangle.”

It’s a small triangle, measuring two blocks on its longest side, stretching from a parking lot east of Summit Avenue to the former All Church Home campus west of Summit just southwest of downtown. But once it was part of Quality Hill, where Fort Worth’s cattlemen and bankers and physicians built their fine homes. And before it was Quality Hill, it was just prairie between the Trinity River and the Army’s Fort Worth.

It’s a small triangle, measuring two blocks on its longest side, stretching from a parking lot east of Summit Avenue to the former All Church Home campus west of Summit just southwest of downtown. But once it was part of Quality Hill, where Fort Worth’s cattlemen and bankers and physicians built their fine homes. And before it was Quality Hill, it was just prairie between the Trinity River and the Army’s Fort Worth.

At each corner of the triangle can be found a story of iron.

In the first corner of the Iron Triangle is William A. Duringer. Duringer and his family came to Fort Worth from Illinois in 1875 when he was fourteen, settling south of town on Deer Creek near Crowley. He attended Tulane University medical school and in 1885 began his practice in Fort Worth in a one-room building at 6th and Houston streets. He soon joined Dr. William Paxton Burts and Dr. Julian Theodore Feild at 3rd and Main streets. He remained at that location more than thirty years. (William’s brother Robert Ewing Duringer would become a Tarrant County commissioner.)

In the first corner of the Iron Triangle is William A. Duringer. Duringer and his family came to Fort Worth from Illinois in 1875 when he was fourteen, settling south of town on Deer Creek near Crowley. He attended Tulane University medical school and in 1885 began his practice in Fort Worth in a one-room building at 6th and Houston streets. He soon joined Dr. William Paxton Burts and Dr. Julian Theodore Feild at 3rd and Main streets. He remained at that location more than thirty years. (William’s brother Robert Ewing Duringer would become a Tarrant County commissioner.)

Dr. Duringer lived at 1402 Summit Avenue between cattleman capitalists Burk Burnett and W. T. Waggoner. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Libraries.)

Dr. Duringer served as surgeon for the Southern Pacific, Orient, Rock Island, Frisco, and Katy and Central railroads, as chief surgeon for Armour packing plant, and as consulting surgeon for the fraternal Order of Eagles. He was a member of the board of All Saints Hospital, president of the medical school of Fort Worth University, and visiting surgeon of St. Joseph Infirmary. Duringer was president of the Hust Lake Art Club.

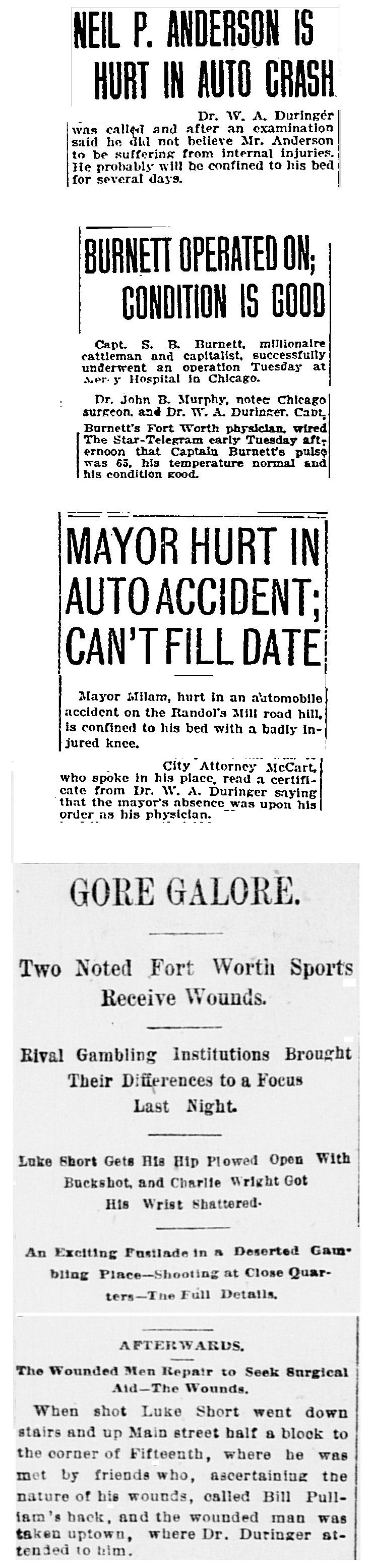

Dr. Duringer was one of Fort Worth’s few doctors late in the nineteenth century, and he was called upon to treat a variety of patients: victims of morphine overdose and typhoid fever and streetcar and train accidents. Dr. Duringer also treated prominent residents such as cotton king Neil P. Anderson, neighbor Burk Burnett, and Mayor Robert F. Milam. And after gambler/gunfighters such as Charlie Wright and Luke Short got out their instruments of iron and steel, Dr. Duringer got out his instruments of iron and steel to patch them up.

Dr. Duringer was one of Fort Worth’s few doctors late in the nineteenth century, and he was called upon to treat a variety of patients: victims of morphine overdose and typhoid fever and streetcar and train accidents. Dr. Duringer also treated prominent residents such as cotton king Neil P. Anderson, neighbor Burk Burnett, and Mayor Robert F. Milam. And after gambler/gunfighters such as Charlie Wright and Luke Short got out their instruments of iron and steel, Dr. Duringer got out his instruments of iron and steel to patch them up.

Old age eventually stilled Dr. William A. Duringer’s instruments of iron and steel. He died in 1937 at age seventy-five. (The “C.” in “W. C. Duringer” is incorrect. Dr. William Commodore Duringer was the son of William A.’s brother Robert.)

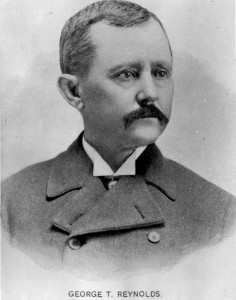

In the second corner of the Iron Triangle is George T. Reynolds (1844–1925).

In the second corner of the Iron Triangle is George T. Reynolds (1844–1925).

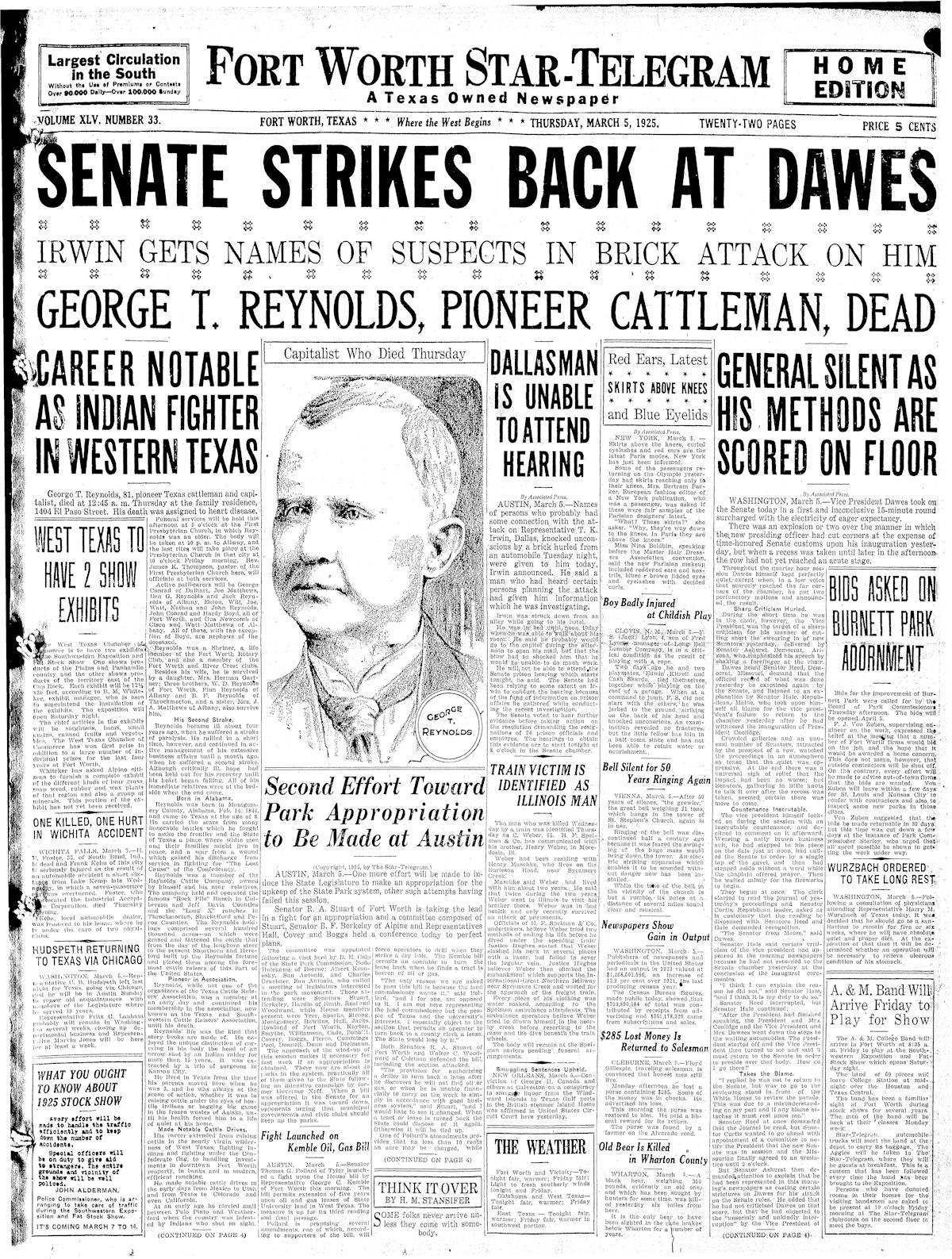

Born in Alabama, George T. Reynolds came to Texas with his family when he was eight. His first job as a boy was driving a mule that furnished power to a cotton gin in Shelby County. Four days of work earned George one dollar. But George T. Reynolds would die a millionaire, one of Fort Worth’s capitalist-cattlemen, a member of the Fort Worth Club and River Crest Country Club. (Photo from Cattle Raisers Museum.)

As a young man Reynolds fought Native Americans as he drove cattle from Mexico to Utah and from Texas to Colorado and California. He fought Native Americans as he carried the mail on horseback between Palo Pinto and Weatherford. During the Civil War he was wounded and discharged from the Confederate army as the South fought, the Star-Telegram reported, “the Lost Cause.” He returned home from the war with $300 in Confederate bills, worth ten cents on the dollar.

In 1868 George and his brother William D. Reynolds formed the Reynolds Land and Cattle Company, and they eventually owned a lot of both (400,000 acres of land, 20,000 head of cattle) on ranches such as the Rock Pile and the Long X, grazing first longhorns and then Herefords and shorthorns.

George T. Reynolds lived at 1404 El Paso just off Summit Avenue. His fine home and carriage house have been replaced by that great leveler of architecture, the parking lot.

George T. Reynolds lived at 1404 El Paso just off Summit Avenue. His fine home and carriage house have been replaced by that great leveler of architecture, the parking lot.

The long and successful life of George T. Reynolds ran counter to a dream that his father had one night in 1867. George and William and eight other men had gone out to track a band of Native Americans who had been stealing horses. While the brothers were gone, back home their father had a dream one night. At breakfast the next morning he said he had dreamed that George was killed in a fight with Native Americans.

The next day at the mouth of Double Mountain Fork in Haskell County the ten white men indeed encountered the Native Americans they were tracking as the Native American skinned a buffalo. A fight ensued. The white men had guns; the Native Americans had guns and bows and arrows. “The first Indian out,” the Star-Telegram reported, “was calmly shot twice by Reynolds.” During the running fight six Native Americans were killed; George T. Reynolds was shot in the abdomen by an arrow. He pulled out the wooden shaft, but the arrowhead, made of iron or steel, remained inside his body. Reynolds gave himself up for dead.

His father’s dream was coming true.

Companion Si Hough saw that Reynolds was seriously wounded and asked which Native American had shot him. Reynolds told Hough that a Native American in a red shirt had shot him. Hough swore revenge and rode off. Hough, the Star-Telegram wrote, soon returned with the Native American’s scalp.

Hough and the rest of Reynolds’s companions carried Reynolds back to his home sixty miles away. The trip took one day. A doctor was sent for—from 110 miles away. Five more days elapsed before the doctor arrived. But the doctor found that he did not dare remove the arrowhead, firmly embedded in the muscles of Reynolds’s back.

Despite his wound George T. Reynolds rallied, recovered, and soon was back in the saddle, despite the pain caused by that iron souvenir of the battle he carried inside his body.

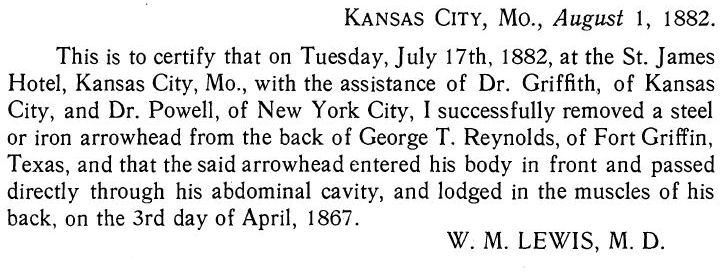

Oh, surgeons did eventually remove that iron souvenir—sixteen years later. One surgeon even signed a certificate:

Interestingly, the Star-Telegram wrote that in the late years of his life George T. Reynolds, who had fought Native Americans so often in earlier days, “traveled extensively, . . . visiting practically all Indian tribes from tropical regions of Mexico to far-away Alaska.”

“Indian fighter” George T. Reynolds died on March 5, 1925.

“Indian fighter” George T. Reynolds died on March 5, 1925.

For the third corner of the Iron Triangle, let’s go even further back in time—before Quality Hill, before the fine homes of Dr. Duringer and George Reynolds, back to 1849, when the area of the Iron Triangle covered virgin prairie, and the Army’s Fort Worth was in its first year. Local historian Julia Kathryn Garrett in her Fort Worth: A Frontier Triumph wrote that two bands of Comanches, totaling two hundred warriors and led by chiefs Jim Ned and Feathertail, traveled separately from Palo Pinto County toward the new fort, intent on wiping it out because it was too close for comfort in those early “There goes the neighborhood” days of white settlement. Jim Ned’s band camped overnight below the bluff of the Trinity River west of the Iron Triangle. Feathertail’s band camped elsewhere. The two chiefs planned to merge their bands to attack the fort. But a white fur trader camped nearby discovered Jim Ned’s camp and rode in the darkness to alert the soldiers at the fort. Fort commander Major Ripley Arnold quickly assembled infantry and cavalry units, who followed the trader back to the bluff with the fort’s only howitzer in tow. The howitzer fired six-pound cast-iron cannonballs. The sleeping Native Americans, surprised by the attack, fought back but soon retreated to Palo Pinto County. None of the soldiers was seriously injured.

Early Fort Worth historian Howard Peak recounts a similar story in his book A Ranger of Commerce or 52 Years on the Road but says the events told by Garrett took place in two battles, not one.

A caveat: Historian Dr. Richard Selcer says the battle, which Garrett called “the last large-scale Indian battle in the environs of Fort Worth,” never occurred.

A caveat: Historian Dr. Richard Selcer says the battle, which Garrett called “the last large-scale Indian battle in the environs of Fort Worth,” never occurred.

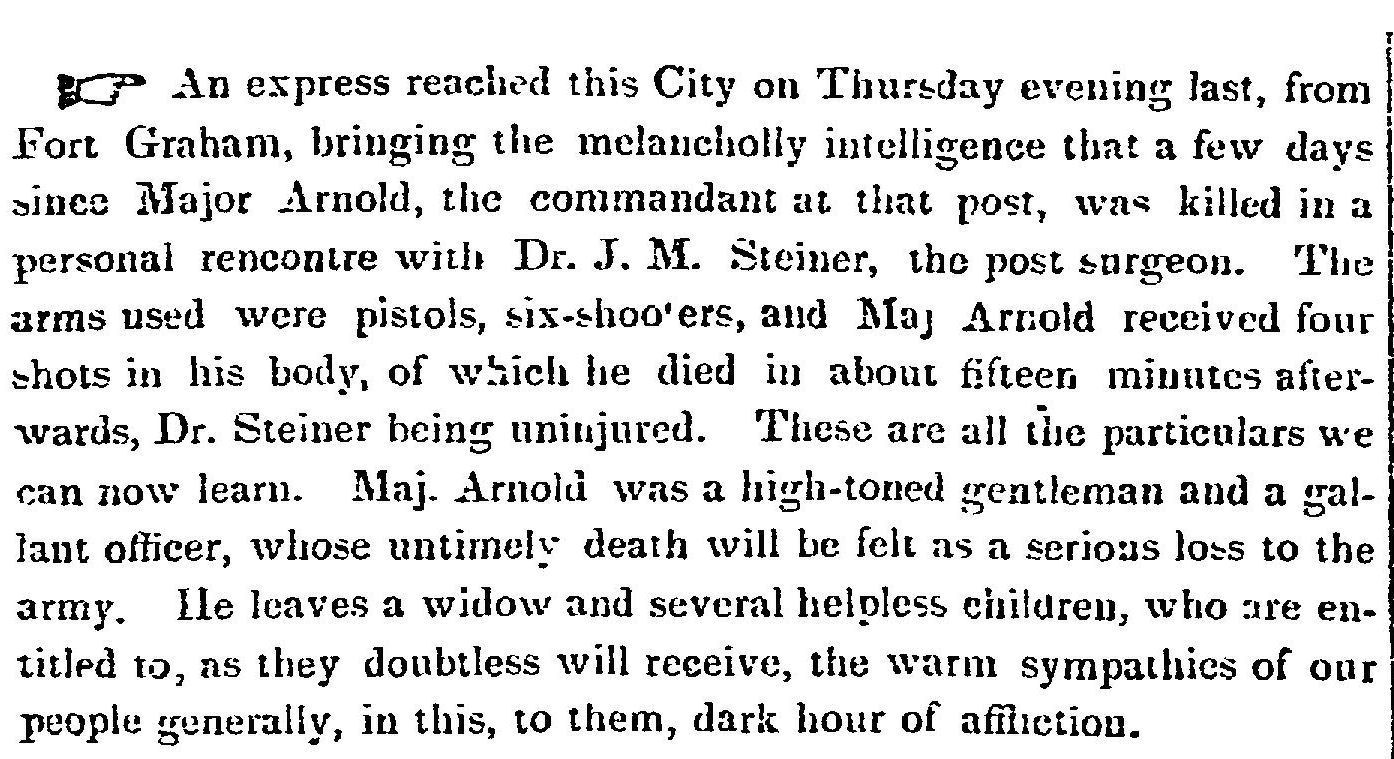

But without doubt Major Ripley Arnold, like many a soldier, lived by iron and died by iron.

But without doubt Major Ripley Arnold, like many a soldier, lived by iron and died by iron.

After Arnold was transferred from command of Fort Worth to command of Fort Graham (near Hillsboro), in 1853 a dispute between Arnold and post surgeon Josephus Steiner turned violent. Arnold fired his pistol twice at Steiner, missing both times. The post surgeon pulled an instrument of iron and steel—his pistol—and fired four times. He didn’t miss once. Arnold died within minutes.

After Arnold was transferred from command of Fort Worth to command of Fort Graham (near Hillsboro), in 1853 a dispute between Arnold and post surgeon Josephus Steiner turned violent. Arnold fired his pistol twice at Steiner, missing both times. The post surgeon pulled an instrument of iron and steel—his pistol—and fired four times. He didn’t miss once. Arnold died within minutes.

Major Ripley Allen Arnold is buried in Pioneers Rest Cemetery.

Major Ripley Allen Arnold is buried in Pioneers Rest Cemetery.

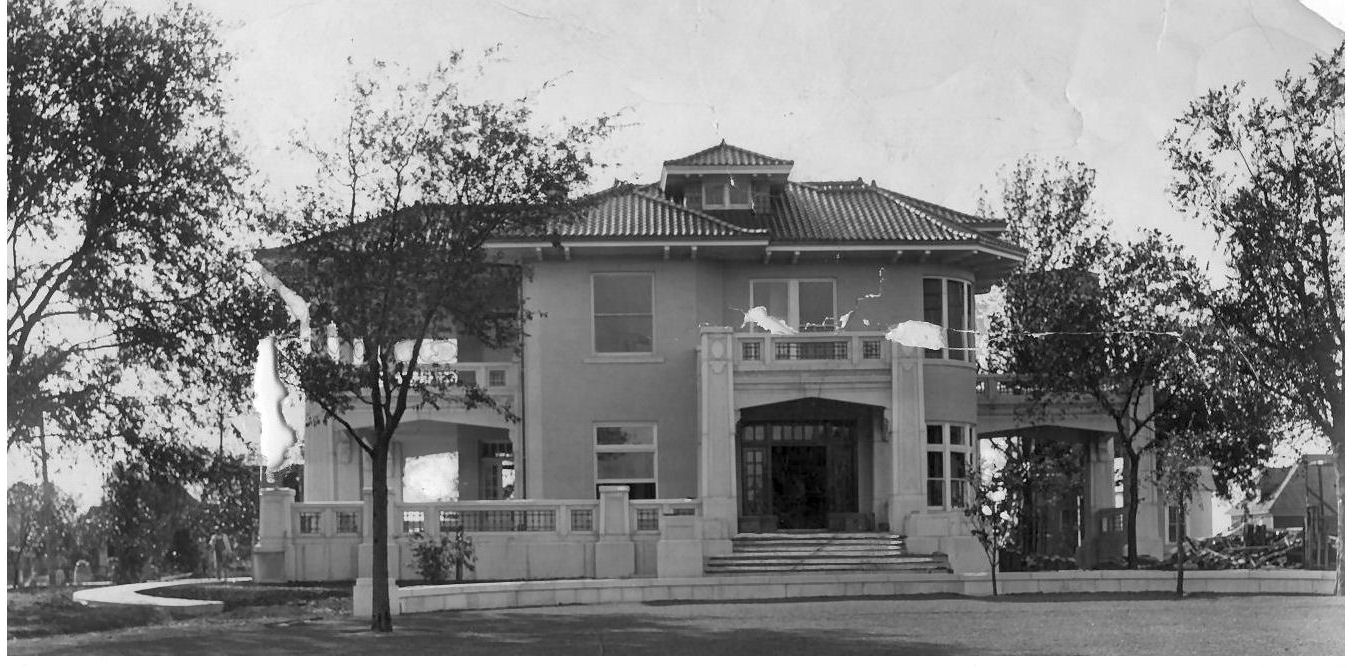

The site of the battle with chief Jim Ned’s band would later become the estate of first attorney Frank Ball (not capitalist Frank Ball) and then cattleman Samuel Burk Burnett at 1424 Summit Avenue. Burnett died in 1922, and soon after the house became the home of All Church Home.

The site of the battle with chief Jim Ned’s band would later become the estate of first attorney Frank Ball (not capitalist Frank Ball) and then cattleman Samuel Burk Burnett at 1424 Summit Avenue. Burnett died in 1922, and soon after the house became the home of All Church Home.

All Church Home demolished the Burnett house in 1962. This Star-Telegram story says a marker on the grounds “commemorates the last stand of the Indians in Tarrant County.” Alas, the marker disappeared, an All Church Home spokeswoman told me. Alas again, the marker was made of concrete, not iron.

All Church Home demolished the Burnett house in 1962. This Star-Telegram story says a marker on the grounds “commemorates the last stand of the Indians in Tarrant County.” Alas, the marker disappeared, an All Church Home spokeswoman told me. Alas again, the marker was made of concrete, not iron.

Update: Alas no more! Historian Quentin McGown tells me that the concrete marker, erected during Fort Worth’s diamond jubilee in 1923, is safely in his possession and will be preserved at the Tarrant County archives.

Do you have any history on the Reynolds’ home on El Paso st.. My best friends grandmother lived really close to All Church Home and our 6th grade teacher and her husband, Pat Dodson, who was vice principal at Poly, lived on El Paso and we used to walk over to see her. Did that house ever belong to Pat and Marie Dodson?

Patrick Sparks Dodson lived at 1208 El Paso in 1940 when he was a vice principal. He was still there in 1952. George Reynolds lived at 1404 El Paso. House was built about 1900, an addition designed by Sanguinet and Staats was added in 1922. House remained in the family until 1935, when it was sold to the State Medical Association of Texas. The Red Cross and an insurance company also occupied the house later. Looks like it was torn down about 1994. Although the address of his house was El Paso Street, his carriage house later had a Ballinger Street address.

Brother William’s carriage house still stands nearby on West Jarvis.

My 1st job (in high school) was working in the claims dept. of Intl. Service Ins. Co., which was in the George Reynold’s house. I didn’t know its story when I was 17, but I knew that house had a

great history. I loved it. And I loved running up & down the stairs having rubber band fights with a fellow employee. You could do things like that back then.

A great memory, Sarah. So much of Quality Hill still existed into our lifetime. Almost all of it gone now.

Where prey tell are these men buried? Methinks Reynolds iis buried at Oakwood. But the others? Only you can tell us,your gentle and curious readers.

Duringer is in Oakwood, Arnold in Pioneers Rest. William D. Reynolds is in Oakwood, but George T. went “back home” to Shackelford County (Albany).