Below is the vacant lot at 1203 East Leuda Street on the near East Side. On the left is a building that housed Adolph Schilder’s neighborhood grocery store in the 1920s and 1930s.

The frame house of five hundred square feet that stood on this now-vacant lot was built in 1900 and demolished about 2002. The sidewalk, as if in denial, still leads up to a small porch that no longer exists.

The frame house of five hundred square feet that stood on this now-vacant lot was built in 1900 and demolished about 2002. The sidewalk, as if in denial, still leads up to a small porch that no longer exists.

But really there is no such thing as a vacant lot, is there? Even a vacant lot is full—full of the history of the people who lived in the house that once stood there. For example, in researching that grocery store next door I came across the story of Hattie Cole. She was interviewed by the Federal Writers’ Project in 1937 when she was living at 1203 East Leuda with her daughter and son-in-law. No doubt Hattie Cole often sat on the small porch that no longer exists.

By the time Hattie Cole was interviewed in 1937 she was an old woman. As an African-American child of her place and time, eighty-three years earlier, in 1854, she had been born into slavery. She and the rest of her family were owned by Ebenezer Hearne (1817-1869), who was a cousin of Christopher Columbus Hearne, for whom the town of Hearne is named. The Hearnes owned cotton plantations in Robertson County. Ebenezer Hearne’s plantation was named “Estate Place.”

Hearne owned about one hundred slaves. He had traded one slave to Jack Johnson, an adjacent plantation owner, for Hattie’s father and had allowed Hattie’s parents to marry and live together.

When the Federal Writers’ Project transcribed the oral histories of former slaves, it retained their dialect and their words. Reading the dialect might be difficult for some, but here is the story of Hattie Cole, who survived slavery to live where the sidewalk ends:

“My name now am ‘Hattie Cole.’ ’Twas ‘Hattie Johnson’ an’ befo’ dat ’twas ‘Hearne.’ ‘Hearne’ am my old marster’s name. Now, my age. I’se know dat ’cause my fo’ks gits de statement f’om marster Hearne w’en [Confederate] surrendah comes. ’Tis marked on de statement dat I’se bo’n in 1854. My daughter figure it fo’ me, an’ ’tis eighty-three yeahs old I’se am. Sho, she has to figure it fo’ me . . . ’cause I’se bo’n in slavetime an’ gits no edumacation.

“Whar I’se bo’n am in Robertson County, Texas, neah de Brazos River. Marster Eb Hearne . . . owned both my parents. My father am bo’n on marster Jack Johnson’s plantation dat am next to we’uns.”

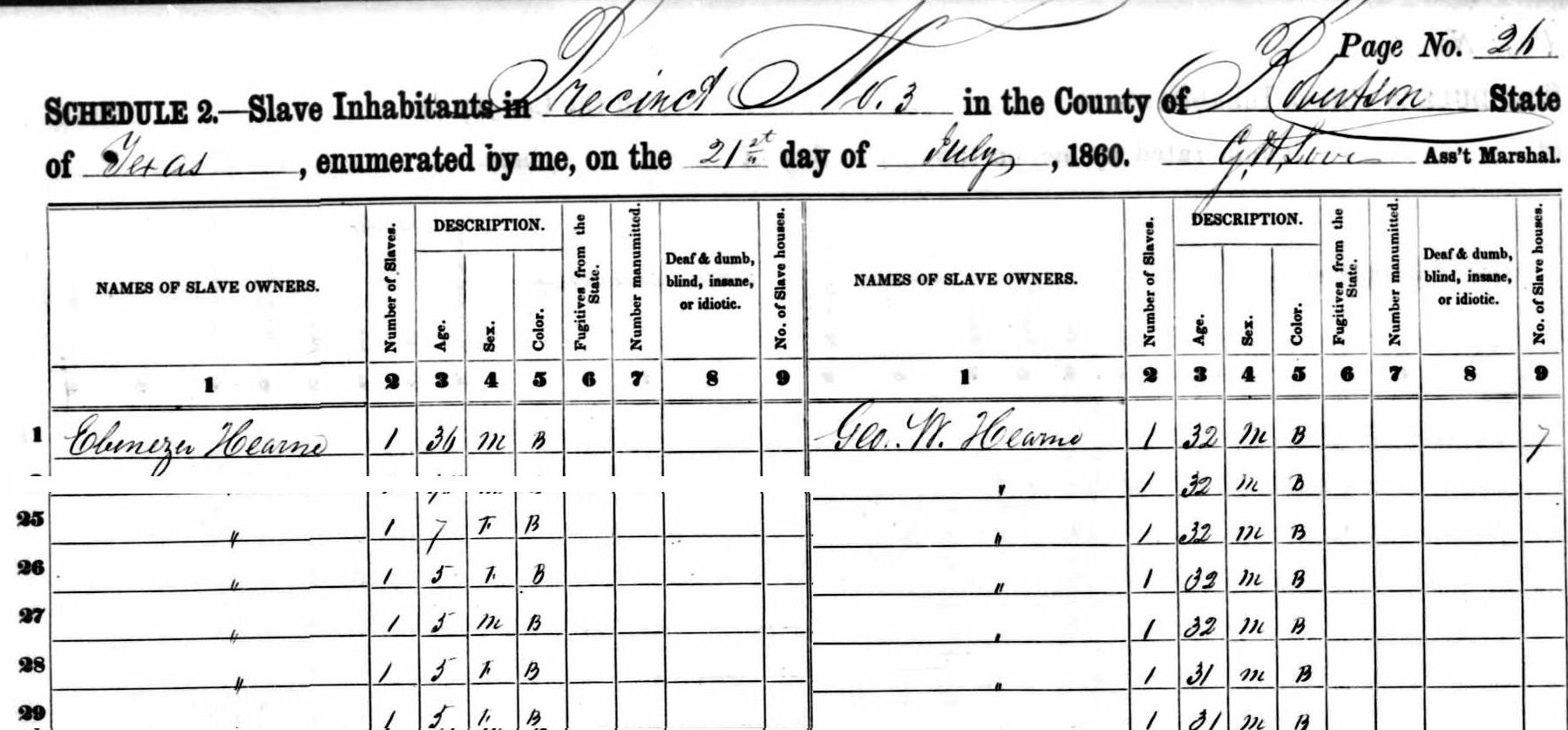

The slave schedule of the 1860 census for Robertson County includes the slaves of Ebenezer Hearne. Because Hattie Cole was born in 1854, one of the females aged five or seven is probably her.

The slave schedule of the 1860 census for Robertson County includes the slaves of Ebenezer Hearne. Because Hattie Cole was born in 1854, one of the females aged five or seven is probably her.

Hattie Cole continues her story:

“Marster Hearne, Johnson, an’ tudder marsters have de ’greement ’bout de mai’iage business. ’Twas lak dis, if a cullud man on Marster’s place wants a woman on tudder place, de marsters make a trade so de couple can be together. W’en my father wants to mai’y my mammy, marster Hearne traded tudder slave fo’ my pappy, an’ dat way, Father am brought to live wid Mammy on de Hearne place.

“De way de marsters do ’bout de mai’iage am awful good w’en ’pared wid what am on lots ob plantations. ’Twas lak cattle, some ob dem am used. Deys fo’ced to live wid de person de marster says.

“Do we’uns have de weddin’ in slavetime? Man, yous know bettah dan dat. De cullud fo’ks jus’ ’gree ’twix demse’ves dat dey be man an’ wife. Oh, deys have ceremony dat deys ’ranged. ’Twas steppin’ over de broom together dat am put on de flooah, wid thar hands clasped.

“I’se guess yous wants to know ’bout de plantation. ’Twas a big place. De marster . . . owned all de land far back to de Brazos River. . . . Thar am over two hunnerd cullud fo’ks dat lived in de qua’tahs. ’Twas one fam’ly to de cabin, an’ de cabins am one-room log huts wid no flooahin’ in dem. . . . We’uns sleep in de bunks wid straw ticks. We’uns don’t have any chairs, ’twas benches we’uns sat on. ’Twarn’t any stove, jus’ fireplace whar de cookin’ am done.

“Each fam’ly does thar own cookin’. De rations am given out ever’ Sunday mo’nin’ at nine o’clock. No, dey don’t measure de rations, dey gives ’cordin’ to de size ob de fam’ly an’ what de fam’ly asks fo’. On Sunday mo’nin’ all de cullud couples line up w’en de bell rings. De couples goes together wid a bushel basket. First deys pass by de smokehouse an’ git de beans, an’ co’n meal, an’ taters an’ sich. Den dey goes to tudder shed whar de ’lasses, brown sugar, an’ honey am stored. De milk an’ buttah am given each day. ’Twas an’ old man, Jerry am his name, dat come ever’ night wid de milk an’ buttah, same wid de eggs w’en thar am any.

“Yas, sar, Marster ’lows we’uns all we’uns wants. If we’uns runs short, we’uns calls fo’ mo’ ob dis or dat ration. Thar am no reason fo’ fussin’ ’bout de rations. Far as de rations am, ’twas bettah dan sich as I’se gits now or since surrendah. I’se sho wish I’se have so good rations now.

“De wo’k am all ’ranged ’cordin’ to rule. I’se use to lak to watch dem in de mo’nin’ w’en deys gits ready fo’ wo’k. . . . De bell rings, den yous see de cullud fo’ks pilin’ out ob de cabins an’ gwine to de field, de shops, an’ tudder places whar deys wo’k. . . . Some goes to de shoeshop, some to de carpenter shop, some to de weavin’ room, an’ so on. Den thar am big herd ob cows, an’ de milkers goes to de milkin’. Yous heah dis one an’ dat one shoutin’ to somebody ’bout dis an’ dat, an’ ever’thing am in a hustle. Heah an’ thar yous heah some ob dem singin’. It makes me lonesome w’en I’se think ’bout it.

“Most ob de cullud fo’ks am happy ’cause deys am fed good, an’ de marster am reasonable ’bout de wo’k. He ask de cullud fo’ks to wo’k steady but don’t overrush. If someone feels bad, all deys have to do am tell de marster or de overseer, an’ dey goes to de cabin an’ lays down. W’en someone suffer too much wid some misery, de marster calls de doctah. If it am small misery, de marster ’tend to it himse’f. He use herb medicine. If I’se gits sich care now, I’se be glad. Now, m’ybe I’se gits medicine, an’ m’ybe no.

“Whuppin’s am not so often, an’ w’en ’tis given, dey don’t tie de cullud fo’ks down to a post or put dem over de barrel. Dey jus’ puts dey face down on de ground, den dey am lashed wid a rawhide. De marster don’t ’lows fo’ to draw blood. Co’se thar am wales on thar body. De whuppin’s am given mos’ly ’cause young fo’ks goes off de place an’ gits catched at it.

“De marster am pa’ticular ’bout de young fo’ks gwine off de place. He don’t ever ’lows de cullud fo’ks to go to parties on tudder place. We’uns not even ’lowed to go off de place to chu’ch. De marster have de chu’chhouse on de place, an’ thar we’uns worship on Sunday. We’uns have one ob de cullud fo’ks lead in service. We’uns pray an’ sing.

“’Cause de marster am so tight ’bout lettin’ de cullud fo’ks go off to ’joy demse’ves once in awhile, de young fo’ks breaks de rule. De way dey gits catched am ’cause dey stays overtime. If dey gits back befo’ daylight, dey can sneak in, but aftah daylight, someone can see dem.

“No, sar, no, sar! Thar am no parties on Marster’s plantation. Him says ’tain’t fo’ parties he have de plantation but ’tis fo’ wo’k.”

Hattie Cole continues her story: Verbatim: “I’se Bo’n in Slavetime” (Part 2)

Wow, I was wondering what that building was. Thanx for the info

Hello,

We are in the process of renovating 1203 East Leuda Street. We are looking for any pictures of the house as it was originally built. This house is historic and as such, we want to maintain its originality as much as possible. Thank you very much for your valuable help

Dixon Kanyinda: I have e-mailed you some links and documents. I hope they help.

Truly enlightening and enjoyable!

Thanks, Doug. The Federal Writers’ Project did us a great service.