Hattie Cole was born into slavery (see Part 1) in 1854. After emancipation—when she was about eleven—her family continued to work on Ebenezer Hearne’s Estate Place plantation in Robertson County for several years. Hattie married Jack Johnson (as Hattie had, he carried his master’s surname) in 1870 and had two children before his death in 1880. Hattie married Lewis Cole in 1885. Two more children were born. The Cole family moved to Fort Worth in 1892. After Lewis died in 1906, Hattie Cole lived with her daughter and son-in-law.

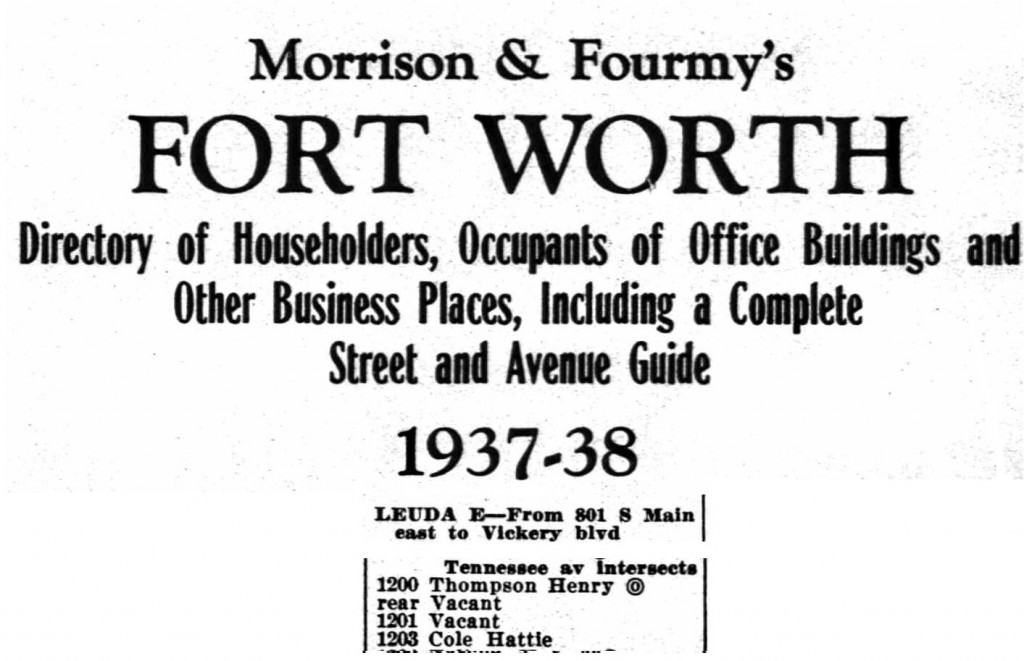

In 1937, when Hattie Cole was eighty-three years old and living at 1203 East Leuda Street on the near East Side, she was interviewed by the Federal Writers’ Project. Note: When the Federal Writers’ Project transcribed the oral histories of former slaves, it retained their dialect and their words; one of the terms that Hattie Cole used for African Americans is outdated today, another is offensive. Here, in her own words, is Hattie’s story of life after emancipation:

“W’en [Confederate] surrendah comes, den life changed some. . . . No, sar, ’twarn’t any time dat de marster called all us together an’ told we’uns dat we’uns am free. De Bluecoats come an’ does it. One ob de sojers reads a papah to we’uns. . . . Him says, ‘Yous am free an’ citizens ob de United States. Dat means yous can go whar yous lak.’ But de sojers am mistaken ’cause ’twarn’t so. We’uns am not ’lowed to do as we’uns please. We’uns am in’fered wid by de Ku Klux Klan, ‘white caps’ we’uns calls dem. Dat am o’gnation [organization] dat come aftah de wah.

“My fo’ks stays on de marster’s plantation after we’uns am freed an’ wo’ks de land on shares. Dey gits ha’f what am raised. . . . De cullud fo’ks stahts to have de parties an’ dances. Well, it goes all right fo’ a while, den de Klux shows up, an’ de fust thing we’uns know, de Klux am gwine fust to one place an’ de tudder an’ whups de cullud fo’ks. Yas, sar, dey rides right up to de house, breaks right in de dooah, pulls marster nigger outside, an’ den whups him wid de rawhide whup.

“W’en we’uns have a dance or party, deys liable to come any moment an’ give yous hell. At fust most ob de niggers resent de hindrance. Yas, sar, dey sho am ’dignant ’bout it, so deys try to put up a fight. Well, w’en dey does dat, it makes it worster.

“A party ob cullud men ’cides to throw red pepper in de Klux face w’en dey bust in de dooah. So deys have de party, an’ de Klux comes. W’en dey bust in de dooah, de cullud mens lets dem have it. Co’se, de Klux have hoods on, an’ dat saves dem f’om much ob de red pepper. ’Twarn’t ’nough ob dem dat am ’fected to save de cullud mens. Two ob dem gits a good whuppin’. De rest ob we’uns am saved ’cause we’uns runs off to de woods. De place whar deys come belong to Bud Brown, an’ de next week his cabin am set on fire, an’ de cabin dat belongs to a tudder cullud man am burned.

“. . . Dat condition keeps fo’ long time, but after while, it dies down, an’ de cullud fo’ks goes on havin’ parties an’ dances ’gain.

“I’se stayed wid my fo’ks ’til I’se mai’ied an’ den stayed on de plantation. My husband rented land f’om de marster Hearne an’ farmed on shares. My two chilluns am bo’n on de place. My fo’ks wo’ked land, an’ my mammy wo’ked fo’ de marster as de cook an’ de nurse fo’ de marster’s chilluns. De chilluns always call my mammy ‘Black Mammy.’ Dey sho think de world ob her. Deys go to her fo’ ever’thing an’ wid all dere troubles. She raised all fouah ob de chilluns.”

By the time Hattie was interviewed in 1937 the grocery store next door had closed.

By the time Hattie was interviewed in 1937 the grocery store next door had closed.

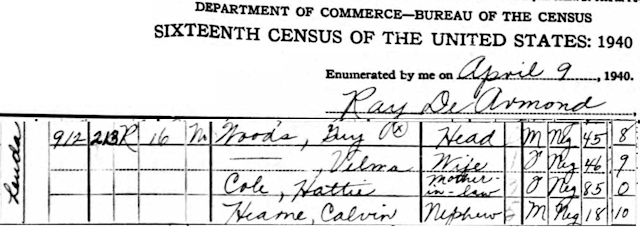

This is Hattie’s entry in the 1940 census, taken on April 9 when she was eighty-five. Note that one family member retained the “Hearne” surname. Also note that in the far-right column Hattie listed a zero for years of education. She was the only person on that census sheet who listed zero years of education.

This is Hattie’s entry in the 1940 census, taken on April 9 when she was eighty-five. Note that one family member retained the “Hearne” surname. Also note that in the far-right column Hattie listed a zero for years of education. She was the only person on that census sheet who listed zero years of education.

Hattie continues her story:

“My husband moved we’uns to a tudder place neahby w’en we’uns left de marster’s place an’ farmed. He died in 1880. After five yeahs I’se mai’ed de second time an’ stayed right on de farm ’til 1892, den we’uns moved to Fort Worth. He wo’ked heah at common labor ’til he died in 1906.

“After my husband dies, I’se wo’ked fo’ white fo’ks, doin’ housewo’k ’til ten yeahs ago. Den I’se lived wid my daughter. De last few months I’se been gittin’ a pension f’om de state. Dey pays me $15 a month. I’se gits by on dat.”

At this point the Federal Writers’ Project interviewer apparently asked Hattie Cole if she had ever voted:

“Votin’, does I’se ever do dat? Oh, yous knows bettah den ask dis old nigger sich. Why, I’se never bother dis old head wid sich, dat am fo’ de men. . . . My fust husband goes to vote once, but dat am all. Jus’ once. Some cullud fo’ks coax him to vote, an’ ’twas at Hearne, Texas, he goes. He gits hit over de head wid a blackjack, an’ dat am all he wants wid sich truck. After some fellows wants him to vote ’gain, dey says ’tis de duty ob a good citizen to vote. Jack tells dem if dat am de case, he am one nigger dat don’t have good ’nough head to be a good citizen.

“I’se lived dis long widout votin’, an’ I’se guess I’se can make it de rest ob de way, an’ ’tain’t a long way now.”

And how was “de rest ob de way” for Hattie Cole, who lived where the sidewalk ends? What became of this woman who was born into slavery and lived into the lifetime of Martin Luther King Jr.?

And how was “de rest ob de way” for Hattie Cole, who lived where the sidewalk ends? What became of this woman who was born into slavery and lived into the lifetime of Martin Luther King Jr.?

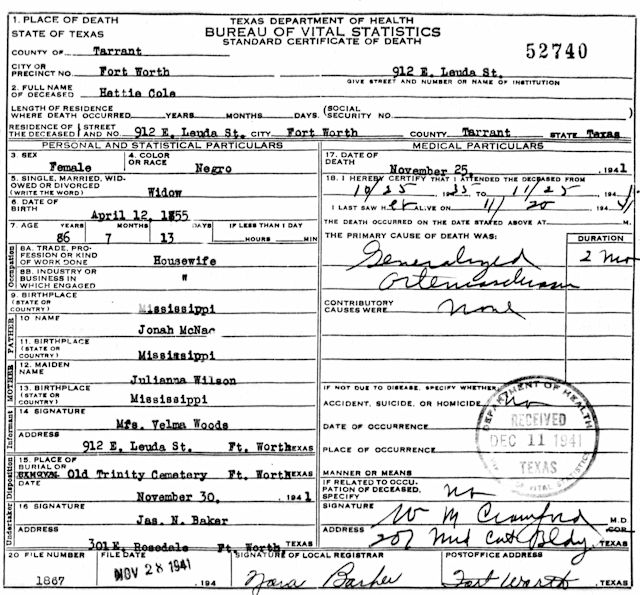

Hattie Cole died on November 25, 1941 and is buried in New Trinity Cemetery on Northeast 28th Street.

Hattie Cole died on November 25, 1941 and is buried in New Trinity Cemetery on Northeast 28th Street.

Some caveats: (1) Many of the ex-slaves interviewed by the Federal Writers’ Project in the late 1930s had been children during slavery and thus may have received less-harsh treatment (and thus have retained less-harsh memories) than did adult slaves who were no longer alive to be interviewed in the late 1930s. (2) Lacking mechanical recording equipment, the interviewers sometimes took notes during interviews and transcribed the notes afterward, relying on memory, not “taking dictation” as the ex-slaves spoke. (3) The ex-slaves may have told interviewers, who were usually white, what the ex-slaves thought the interviewers wanted to hear (e.g., that white overseers had been kind). (4) The interviews were conducted during the Great Depression, when ex-slaves may have been afraid to endanger their often-precarious financial situation by offending the white establishment of their community.

More memories of former slaves:

Verbatim: Philles and William (“Jesus’ Lamb” and “Dat Old Cuss”)

Verbatim: “We’s Free and It Give Us All de Jitters”

Verbatim: “Us Am de Cons’lation to Each Other”

Verbatim: “I Hears Marster Say Dem Was de Quantrell Mens”

This makes the Civil War real to me. How it affected the citizens in their own words is crucial. I’d love to read more narratives during this time period. It’s also interesting that there were some advantages in slavery. We’re led to believe that it was always horrendously cruel.

Thanks, Susan. I have three other slave narratives in the Verbatim category and a few more planned. There IS a certain “it wasn’t so bad” tone to these narratives, but I have read these caveats: The FWP transcribers were mostly local white people interviewing local black people; the transcribers did not have recording devices and sometimes relied on memory in reconstructing narratives; the ex-slaves, hesitant to give a local white transcriber a negative narrative, may have told the transcriber what they thought the transcriber wanted to hear. Also, a lot of these ex-slaves were young at the time of their slavery and may not have received the same treatment as older slaves. That said, the narratives are valuable resources.