A (cat) tale of two cities: In the first city it was the best of times. In the second city it was the worst of times.

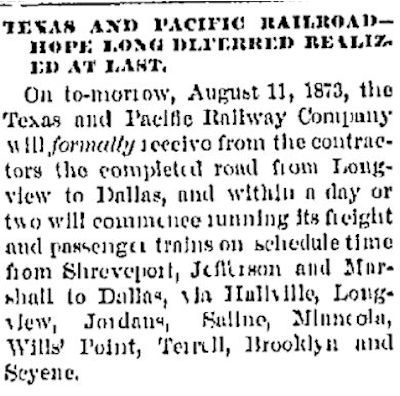

In the first city, on August 10, 1873 the Dallas Weekly Herald announced that the Texas & Pacific railroad track from Longview to Dallas was complete. Dallas now had its second railroad. (The Houston & Texas Central railroad had reached Dallas in 1872.) (The “Brooklyn” listed in the clip today is Forney.)

In the first city, on August 10, 1873 the Dallas Weekly Herald announced that the Texas & Pacific railroad track from Longview to Dallas was complete. Dallas now had its second railroad. (The Houston & Texas Central railroad had reached Dallas in 1872.) (The “Brooklyn” listed in the clip today is Forney.)

In the second city, there was much optimism in 1873 because T&P planned to continue laying track westward from Dallas to give Fort Worth its first railroad. Yessiree, in August 1873 Fort Worth’s future was poised just thirty miles to the east.

But in September the national economic panic of 1873 struck, triggering the “great depression” of the nineteenth century. Not for three long years would T&P lay those thirty short miles of track from Dallas to Fort Worth.

During that three-year delay Fort Worth languished; Dallas, with two railroads to Fort Worth’s none, prospered.

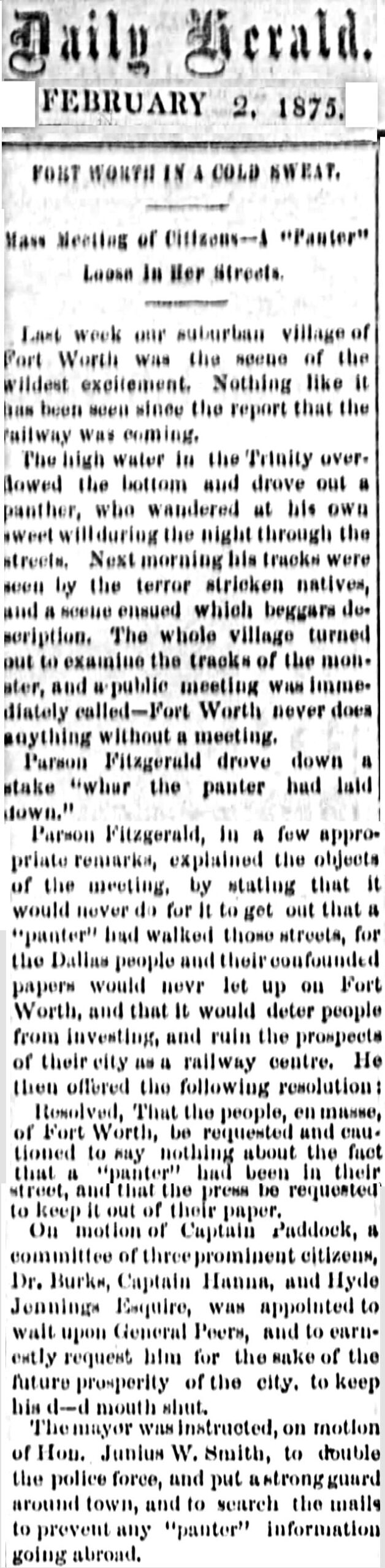

As Dallas prospered and watched Fort Worth languish, on February 2, 1875 Robert E. Cowart, a Dallas lawyer who had formerly lived in Fort Worth, wrote a tongue-in-cheek article in the Dallas Daily Herald in which he claimed that Fort Worth had become such a sleepy “suburban village” that one night a panther had come up from the river bottom, had wandered the downtown streets “at his own sweet will,” and had laid down to sleep on a major city thoroughfare.

As Dallas prospered and watched Fort Worth languish, on February 2, 1875 Robert E. Cowart, a Dallas lawyer who had formerly lived in Fort Worth, wrote a tongue-in-cheek article in the Dallas Daily Herald in which he claimed that Fort Worth had become such a sleepy “suburban village” that one night a panther had come up from the river bottom, had wandered the downtown streets “at his own sweet will,” and had laid down to sleep on a major city thoroughfare.

Cowart wrote that Fort Worth townspeople saw the panther tracks and called a public meeting (“Fort Worth never does anything without a meeting”). A Parson Fitzgerald, Cowart wrote, drove a stake into the ground “whar the pant[h]er had laid down.”

Then “Parson Fitzgerald, in a few appropriate remarks, explained the objects of the meeting by stating that it would never do for it to get out that a ‘pant[h]er’ had walked those streets, for the Dallas people and their confounded papers would never let up on Fort Worth, and that it would deter people from investing, and ruin the prospects of their city as a railway centre. He then offered the following resolution”:

“Resolved, That the people, en masse, of Fort Worth, be requested and cautioned to say nothing about the fact that a ‘pant[h]er’ had been in their street, and that the press is requested to keep it out of their paper.”

Three town leaders (Burts, Hanna, and Jennings), according to Cowart, also were appointed to warn General J. M. Peers, proprietor of the Peers House on Rusk (Commerce) Street, “to keep his d-d mouth shut.” Apparently the General was prone to hiss and tell.

Lastly, the mayor was told to double the police force, to put a strong guard town, and “to search the mails to prevent any ‘panter’ information going abroad.”

The Dallas Weekly Herald was quick to repeat the gibe later that week:

These clips are from the February 6, 1875 Herald.

These clips are from the February 6, 1875 Herald.

Then came the inevitable retort by Fort Worth in the intercity rivalry. On March 27 the Weekly Herald reprinted a tongue-in-cheek hiss by B. B. Paddock’s Fort Worth Democrat. The Democrat claimed to have found a “communication” from the year 2000 that reported animals roaming among the ruins where Dallas once stood. The Weekly Herald responded to the Democrat by alluding to “indignation meetings” that Fort Worth held in regard to Dallas’s treatment of “the future great city.”

But if readers in Dallas laughed at these gibes, Fort Worth got the last laugh. Rather than take umbrage, Fort Worth took advantage. Rather than “say nothing about the fact that a ‘pant[h]er’ had been in their street,” Fort Worth residents embraced the panther story, made it their own.

Soon Cowtown was also known as “Panther City” or “Pantherville.” Merchants named their businesses “Panther this’ and “Panther that.” One of the first to jump onto the panther wagon was W. D. Thomason.

Soon Cowtown was also known as “Panther City” or “Pantherville.” Merchants named their businesses “Panther this’ and “Panther that.” One of the first to jump onto the panther wagon was W. D. Thomason.

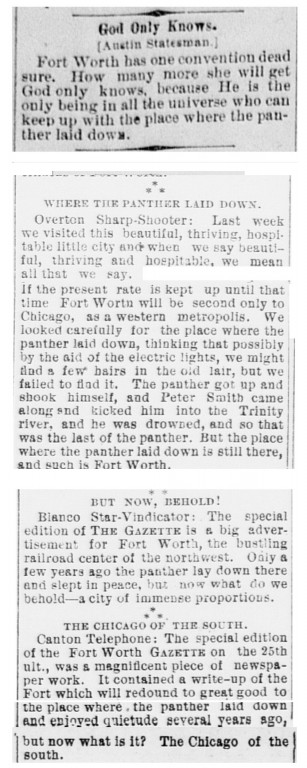

Other newspapers began to refer to Fort Worth as the place “where the panther laid down.” (Overton is in east Texas.)

Other newspapers began to refer to Fort Worth as the place “where the panther laid down.” (Overton is in east Texas.)

And when, on July 19, 1876, three years late, the future finally rolled into Fort Worth, on July 20 the Fort Worth Democrat celebrated by crowing that the “shrill scream” of the whistle of the steam engine roused “the ‘pant[h]er’ from his lair.”

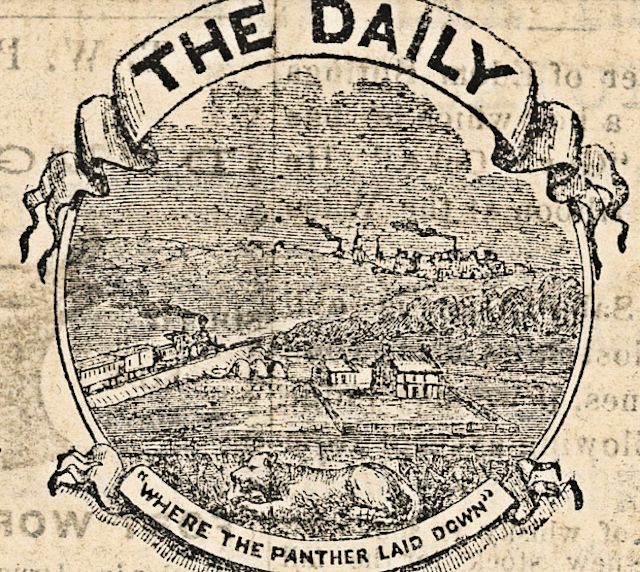

The Democrat adopted a new page 1 nameplate featuring the images of a train and a recumbent panther above the words “where the panther laid down.”

The Democrat adopted a new page 1 nameplate featuring the images of a train and a recumbent panther above the words “where the panther laid down.”

As the baseball craze spread in the late nineteenth century, the town’s baseball team was named the “Panthers.” (The team came to be referred to as the “Cats” by local newspapers only because the word Cats is a shorter headline word than is Panthers.)

As the baseball craze spread in the late nineteenth century, the town’s baseball team was named the “Panthers.” (The team came to be referred to as the “Cats” by local newspapers only because the word Cats is a shorter headline word than is Panthers.)

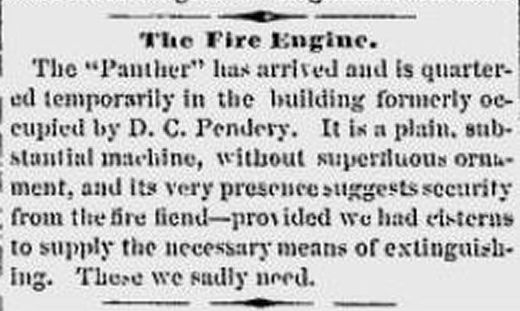

In 1876 the fire department named its first steam pump engine the “Panther.”

In 1876 the fire department named its first steam pump engine the “Panther.”

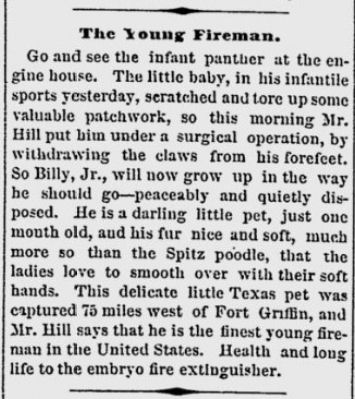

In 1877 the fire department even had a panther mascot, raised from a cub. The city’s first high school (1891) named its yearbook The Panther in 1910. Today that yearbook continues as the Paschal Panther.

In 1877 the fire department even had a panther mascot, raised from a cub. The city’s first high school (1891) named its yearbook The Panther in 1910. Today that yearbook continues as the Paschal Panther.

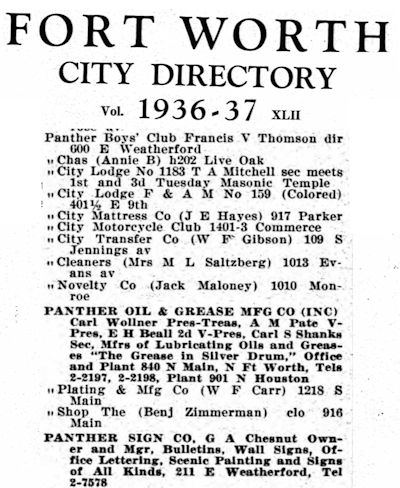

By 1936, when Texas celebrated its centennial, Fort Worth had a Panther Boys’ Club, Panther City lodges (white and black), a Panther City mattress company and motorcycle club, and assorted businesses using the city’s nickname.

By 1936, when Texas celebrated its centennial, Fort Worth had a Panther Boys’ Club, Panther City lodges (white and black), a Panther City mattress company and motorcycle club, and assorted businesses using the city’s nickname.

Likewise, a panther has been on the shield of every Fort Worth police officer since 1912. Today construction is under way on the ambitious Panther Island urban waterfront community project. Around town are Panther City Salon, Panther City Distillery, Panther City Classic Autos, and Panther City BBQ. In fact, today the panther ranks second only to the longhorn in Fort Worth iconography.

Today we have artist Deran Wright’s sculpture on the Tarrant County Administration Building lawn. Per the legend, the bronze panther has “laid down” to sleep near the courthouse. Elsewhere we have a panther fountain in Hyde Park (see header at top of post), panthers carved in bas-relief on buildings, panthers etched on door panes, panthers here, panthers there, panthers ad felinfinitum.

Today we have artist Deran Wright’s sculpture on the Tarrant County Administration Building lawn. Per the legend, the bronze panther has “laid down” to sleep near the courthouse. Elsewhere we have a panther fountain in Hyde Park (see header at top of post), panthers carved in bas-relief on buildings, panthers etched on door panes, panthers here, panthers there, panthers ad felinfinitum.

And it all started on February 2, 1875 with Robert E. Cowart and a barb that Fort Worth turned into a banner.

Related posts:

Meow! Panther City-Big D Rivalry Got Catty Quickly

When “RIP” Stands for “Rivals in Perpetuity”

11:23 a.m. (Part 3): Panther That, Cougartown!

(Thanks to Bud Kennedy for his help.)

Footnote: In 1882 Cowart shot and killed Judge James M. Thurmond in the Dallas County courthouse. Cowart was acquitted.

Nicely done. I always enjoy your work. Some tidbits of information even I was unaware of…

Thanks, Deran. And thank you for your gift to Fort Worth.

Also Dallas ain’t nothin’ but New York City wannabes: Uptown, West End-all NY City terms. What’s next? Will they claim Plano as a borough?

Dallas indeed in many ways is a lot farther away than thirty miles.

Well, at least it was not a skunk. We should have us a big powwow to lay burden over this affair. A hysterical marker should be placed in the location. We should also put in a street car system ‘forin’ we be left behind by Dallas.

Thanks, Mike! And I had no idea Cowart came up with “Panther City”! More serendipity….

Great story. And I am not surprised to read that Cowart was eventually acquitted. Back then when you killed a man you had to work really hard to be found guilty. Shooting an unarmed man in the back might do the trick.

Pingback: Dallas in 1879 — Not a Good Time to Be Mayor | Flashback : Dallas

Thanks, Paula. I have added a link to your post at the bottom of mine. Had no idea what devilry that rascal had gotten up to after the panther letter. I agree: Newspapers of the time were prone to TMI.

Dallas in 1879—Not a Good Time to Be Mayor

Yup, and it even spilled elsewhere around Tarrant County, like the Colleyville Heritage High School Panthers.