The year was 1877. Rutherford B. Hayes replaced Ulysses S. Grant as president; the U.S. government continued to fight the “Indian Wars” west of the Mississippi River; Billy the Kid killed his first man.

And what was going on in Fort Worth in 1877? Fort Worth had a population of about six thousand, less than 1 percent of today’s population. The town had enjoyed railroad service just one year, had been incorporated just four years. In 1877 G. H. Day was mayor. Jim Courtright was city marshal. Jesse Zane Cetti was city engineer. Aldermen included B. C. Evans and Carroll Peak.

And in 1877 B. B. Paddock’s Fort Worth Democrat newspaper had a competitor: the Daily Fort Worth Standard. The few surviving issues of the Standard show us life in Fort Worth in 1877. Let’s start with transportation:

And in 1877 B. B. Paddock’s Fort Worth Democrat newspaper had a competitor: the Daily Fort Worth Standard. The few surviving issues of the Standard show us life in Fort Worth in 1877. Let’s start with transportation:

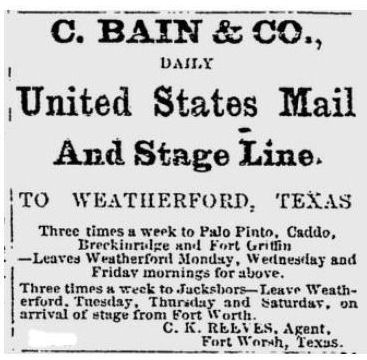

If Fort Worth wasn’t “out west” enough for you, C. Bain provided daily stage service west to Weatherford. From Weatherford there was every-other-day service farther west to Palo Pinto, Caddo, Breckenridge, Fort Griffin, Jacksboro. The stage departed Fort Worth from the El Paso Hotel, located at Main and 4th streets. William Harper also provided “a daily hack line to Decatur.”

If Fort Worth wasn’t “out west” enough for you, C. Bain provided daily stage service west to Weatherford. From Weatherford there was every-other-day service farther west to Palo Pinto, Caddo, Breckenridge, Fort Griffin, Jacksboro. The stage departed Fort Worth from the El Paso Hotel, located at Main and 4th streets. William Harper also provided “a daily hack line to Decatur.”

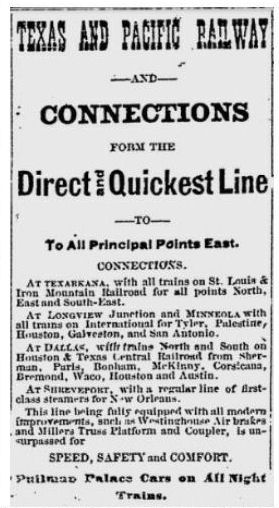

C. Bain would take you west, but the Texas & Pacific railroad connected Fort Worth “to all principal points east.” The coming of the railroad had changed everything in 1876. People could travel long distances faster. Perishable goods (ice, meat, fish, dairy) could be brought to town faster. Now that both the cattle trail and the railroad had come to town, cows and cowcatchers would put Fort Worth on the map.

C. Bain would take you west, but the Texas & Pacific railroad connected Fort Worth “to all principal points east.” The coming of the railroad had changed everything in 1876. People could travel long distances faster. Perishable goods (ice, meat, fish, dairy) could be brought to town faster. Now that both the cattle trail and the railroad had come to town, cows and cowcatchers would put Fort Worth on the map.

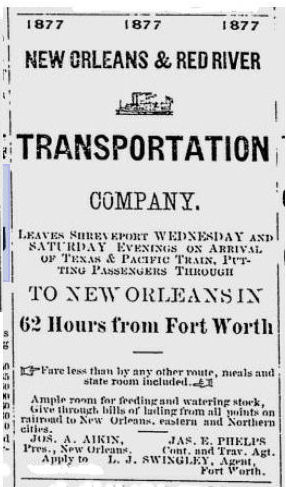

Let’s say you woke up in 1877 with a hankerin’ to witness the spectacle of Mardi Gras. Thanks to the Texas & Pacific and the New Orleans and Red River Transportation Company, you could take the train to the boat to the float. The New Orleans and Red River Transportation Company operated boats from 1875 to 1882. Because the T&P connected Fort Worth to Shreveport, Cowtowners could get to New Orleans by rail and river in just two and a half days. To those early settlers who had spent weeks on a horse or wagon as they migrated west to Texas from Kentucky or Tennessee or the Carolinas, sixty-two hours must have seemed like warp speed.

Let’s say you woke up in 1877 with a hankerin’ to witness the spectacle of Mardi Gras. Thanks to the Texas & Pacific and the New Orleans and Red River Transportation Company, you could take the train to the boat to the float. The New Orleans and Red River Transportation Company operated boats from 1875 to 1882. Because the T&P connected Fort Worth to Shreveport, Cowtowners could get to New Orleans by rail and river in just two and a half days. To those early settlers who had spent weeks on a horse or wagon as they migrated west to Texas from Kentucky or Tennessee or the Carolinas, sixty-two hours must have seemed like warp speed.

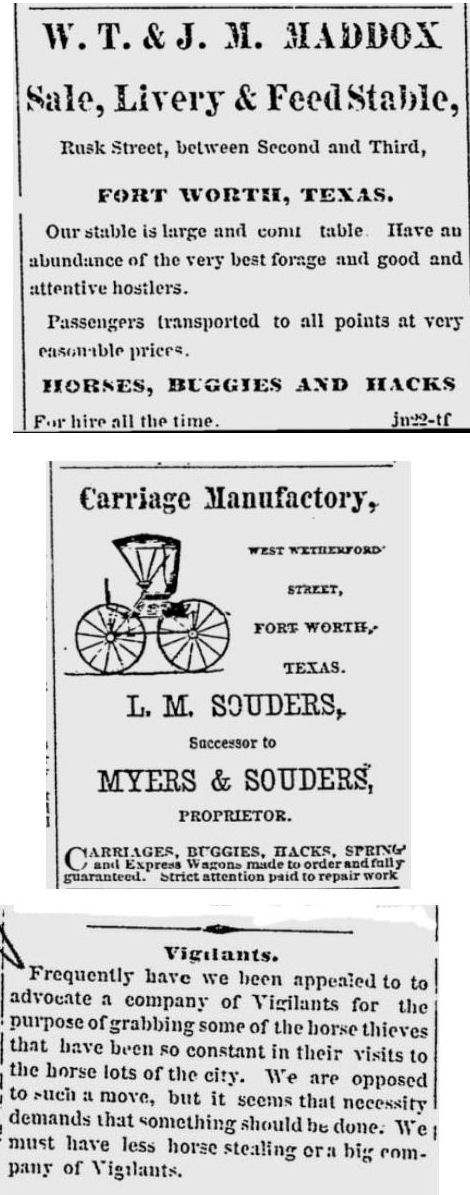

Steam locomotives and steamboats notwithstanding, 1877 was still mostly horse-and-buggy days. The Maddox livery stable on Rusk (now Commerce) Street rented horses and buggies, provided stabling, and ran a four-legged taxi service. On Weatherford Street L. M. Souders made buggies. (W. T. and J. M. Maddox were probably brothers Walter and James, who would become, respectively, county sheriff and city marshal.)

Steam locomotives and steamboats notwithstanding, 1877 was still mostly horse-and-buggy days. The Maddox livery stable on Rusk (now Commerce) Street rented horses and buggies, provided stabling, and ran a four-legged taxi service. On Weatherford Street L. M. Souders made buggies. (W. T. and J. M. Maddox were probably brothers Walter and James, who would become, respectively, county sheriff and city marshal.)

In a short editorial (bottom clip) the Standard demanded an end to local horse theft. Horse theft was the 1877 equivalent of today’s crime of grand theft auto. Early settler J. C. Terrell wrote that only two offenses were not tolerated in early Cowtown: disrupting a religious service and stealing a horse. And no wonder. Think about it: You steal a man’s horse in 1877, you steal his “ride.” You render him a plain ol’ pedestrian. To get his “ride” back, he’s gonna have to chase after you. On foot. Over hill and dale. Over goat-head stickers and red-ant beds and cow patties. Through cactus patches and mesquite thickets. So you can imagine how mad he’s gonna be by the time he catches you.