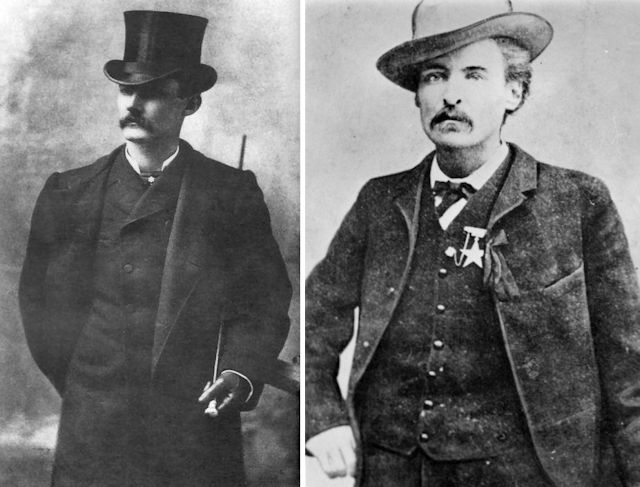

For Fort Worth gambler and gunfighter Luke Short (left, photo from Wikipedia), the month of February was often pivotal. For Fort Worth gambler and gunfighter and former city marshal Jim Courtright (right, photo from Tarrant County College NE), one February in particular was pivotal.

For Fort Worth gambler and gunfighter Luke Short (left, photo from Wikipedia), the month of February was often pivotal. For Fort Worth gambler and gunfighter and former city marshal Jim Courtright (right, photo from Tarrant County College NE), one February in particular was pivotal.

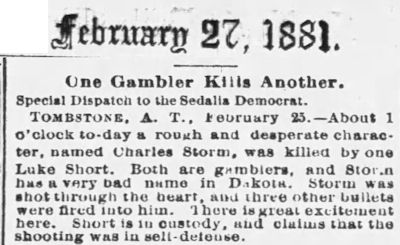

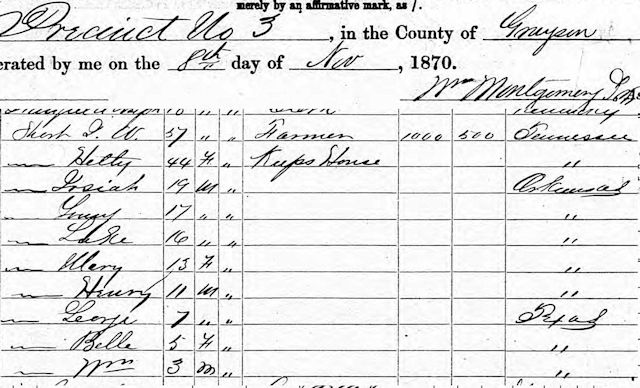

As for Luke Short, for starters he was born on February 19, 1854. It was on February 25, 1881 that he shot and killed fellow gambler Charlie Storms in Tombstone, Arizona. (Short pleaded self-defense and was acquitted.) On February 6, 1883 Short bought an interest in the Long Branch Saloon in Dodge City, Kansas. In February 1884 Fort Worth’s White Elephant Saloon held an open house as it prepared to open, and Short would become a part-owner. But three years later, on February 7, 1887, he sold his share of the White Elephant to fellow gambler Jake Johnson.

As for Jim Courtright, the day after Short sold his share of the White Elephant Saloon—February 8—was pivotal. That night Jim Courtright and Luke Short would meet just outside the White Elephant and take a short walk down the sidewalk and into “wild West” legend.

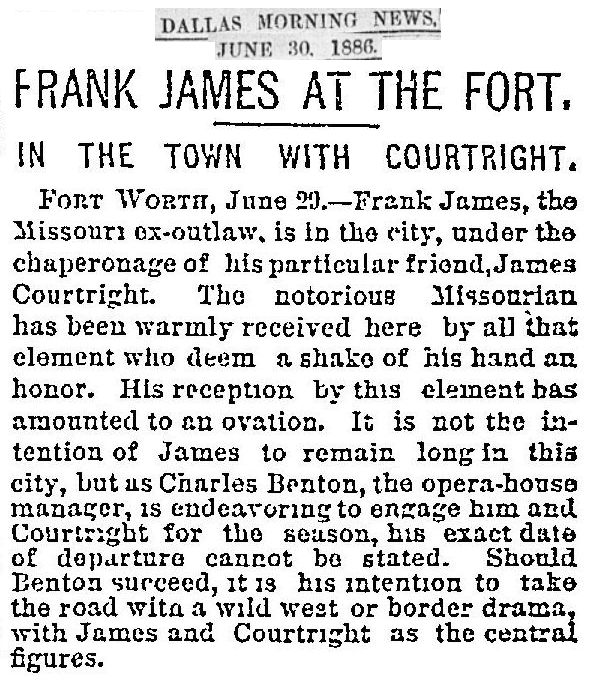

The term wild West is not a term that historians of the twentieth century invented to label, in retrospect, western America of the late nineteenth century. By 1886 the West already knew it was wild. And Jim Courtright, like the James brothers, already had a “wild West” reputation. About eight months before Courtright’s pivotal February, the manager of Fort Worth’s opera house had considered starring Courtright and Frank James, brother of Jesse, in a “wild West” road show.

The term wild West is not a term that historians of the twentieth century invented to label, in retrospect, western America of the late nineteenth century. By 1886 the West already knew it was wild. And Jim Courtright, like the James brothers, already had a “wild West” reputation. About eight months before Courtright’s pivotal February, the manager of Fort Worth’s opera house had considered starring Courtright and Frank James, brother of Jesse, in a “wild West” road show.

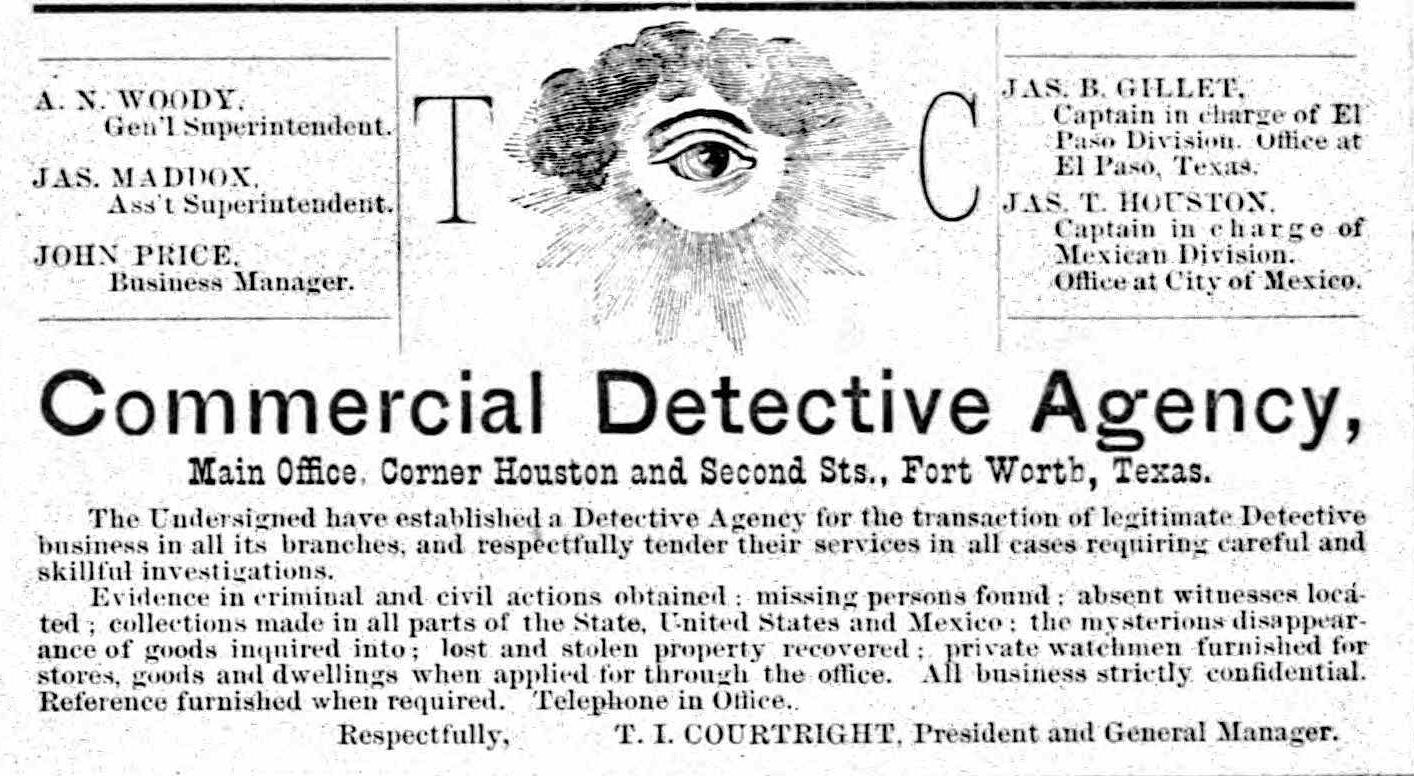

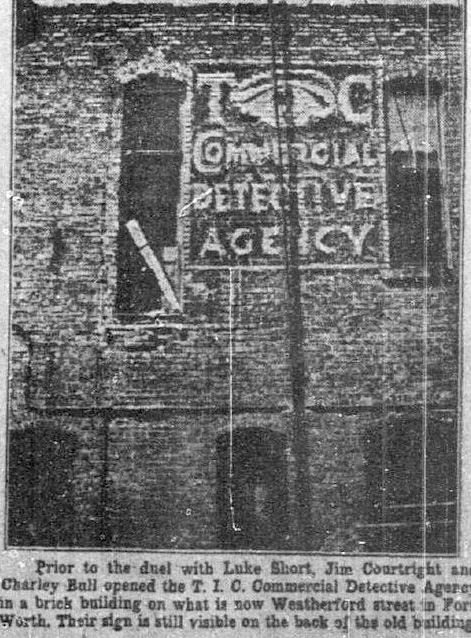

But that wild West show never hit the road, and Courtright was still in Fort Worth in February 1887, operating his T.I.C. (for “Timothy Isaiah Courtright”) detective agency. Courtright had opened the agency about 1884, as an ad in the city directory shows. On his staff was James Maddox, future police chief and brother of Robert E. Maddox, who owned a racehorse named . . . “Luke Short.”

But that wild West show never hit the road, and Courtright was still in Fort Worth in February 1887, operating his T.I.C. (for “Timothy Isaiah Courtright”) detective agency. Courtright had opened the agency about 1884, as an ad in the city directory shows. On his staff was James Maddox, future police chief and brother of Robert E. Maddox, who owned a racehorse named . . . “Luke Short.”

This Dallas Morning News photo of 1929 shows a ghost sign: A wall advertisement for Courtright’s T.I.C. detective agency survived well into the twentieth century.

This Dallas Morning News photo of 1929 shows a ghost sign: A wall advertisement for Courtright’s T.I.C. detective agency survived well into the twentieth century.

According to newspapers of the time, by 1887 Courtright also was operating a protection racket, taking payoffs from Fort Worth saloons and gambling halls.

And so it came to pass that after Courtright had opened his detective agency and while Luke Short had still been a partner in the White Elephant Saloon, Courtright had (1) tried to exact protection payoffs from Short and/or (2) tried to persuade Short to hire him as “special officer” at the White Elephant. Short had refused.

Short’s friend Bat Masterson in 1907 wrote: “It appears that this fellow Courtright . . . had asked Short to install him as a special officer in the White Elephant.” To which Short replied, according to Masterson: “You know that the people about here are all afraid of you, and your presence in my house would ruin my business.”

Courtright, Masterson wrote, got “huffy” and threatened to have Short indicted and his gambling operation closed.

The result was bad blood between Short and Courtright. Or maybe most of the bad blood was Courtright’s. Either way, that bad blood would be spilled at eight o’clock on the eighth night of the pivotal month of February:

“Huffy” and probably liquored up, Jim Courtright went to the White Elephant to confront Short. (Fort Worth was a town on the gambling circuit, and gambling was a fraternity: Also at the White Elephant that night was Short’s friend Bat Masterson.) Gambler Jake Johnson, a friend of both Courtright and Short, also was there. Johnson intercepted Courtright at the White Elephant and told him that he would go into the saloon to fetch Short and bring him outside to talk with Courtright.

After Johnson accompanied Short out of the saloon, Johnson was the only witness to what happened next.

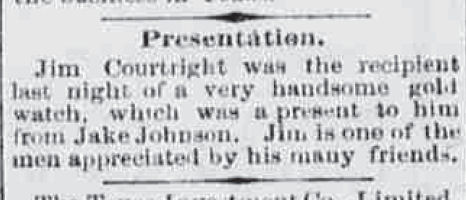

(In 1884 one member of Fort Worth’s gambling fraternity had shown his appreciation of another as Jake Johnson gave Jim Courtright a gold watch. Three years later, on February 8, 1887, Jim Courtright was about to run out of time.)

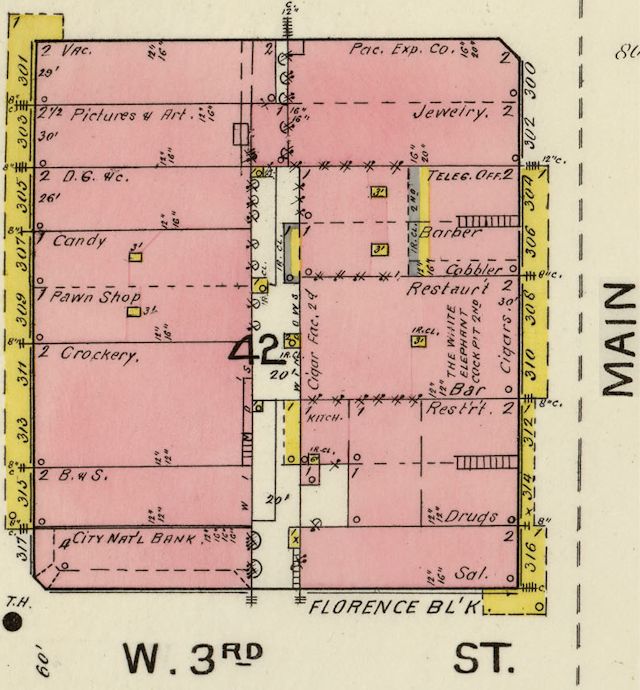

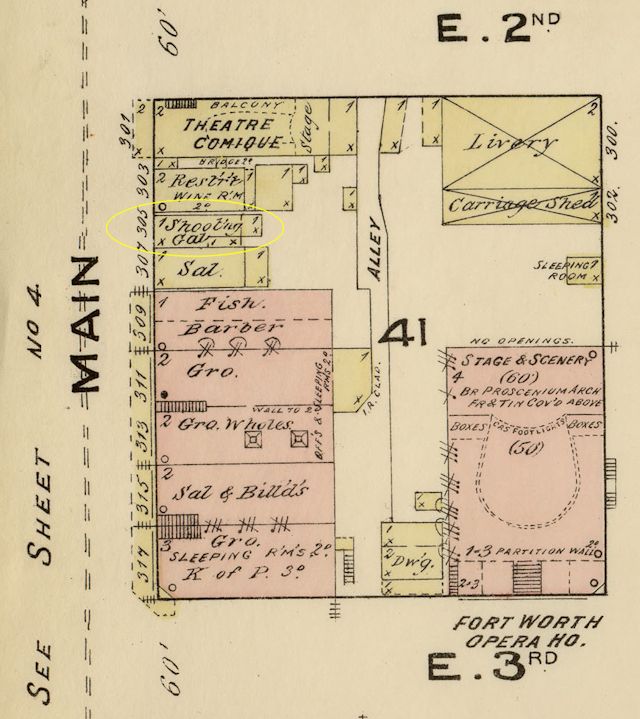

After Short appeared outside the White Elephant, he, Courtright, and Johnson walked away from the saloon, north along the sidewalk in the 300 block of Main Street. In front of Ella Blackwell’s shooting gallery they stopped, talking as they stood three or four feet apart.

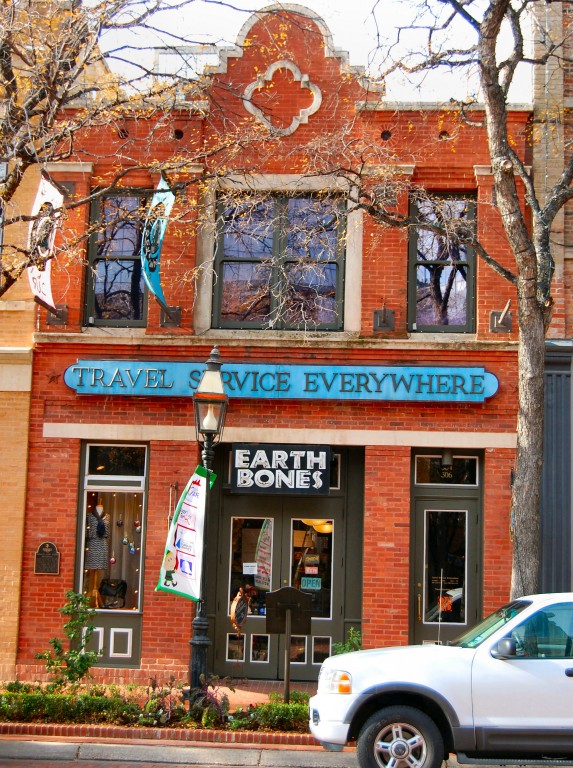

The White Elephant Saloon was an “uptown” saloon, located at 308-310 Main Street, just three blocks from the courthouse, not in Hell’s Half Acre and not at the stockyards, although the “shootout” is reenacted each year outside the White Elephant Saloon at the stockyards. The Morris Building (built in 1906 but rebuilt in 1981) today occupies the site of the original saloon on Main Street.

This 1885 map shows an unnamed shooting gallery at 305 Main across the street from the White Elephant.

This 1885 map shows an unnamed shooting gallery at 305 Main across the street from the White Elephant.

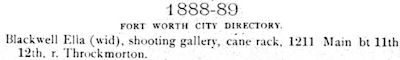

By 1888 Ella Blackwell had moved her shooting gallery nine blocks south into Hell’s Half Acre.

By 1888 Ella Blackwell had moved her shooting gallery nine blocks south into Hell’s Half Acre.

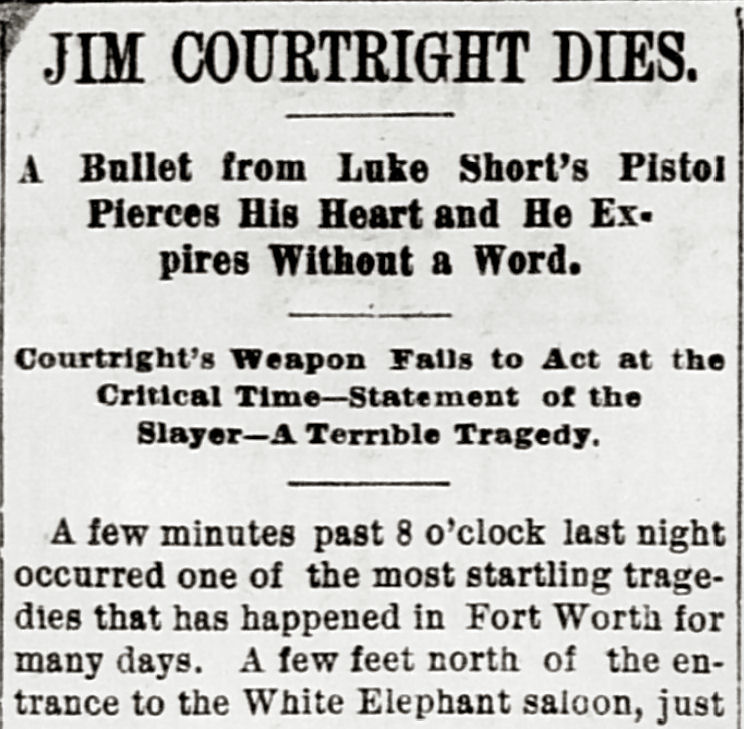

The Fort Worth Gazette later quoted Jake Johnson as he testified about what he had witnessed as Short and Courtright talked on the sidewalk on the night of February 8, 1887: “Luke had his thumbs in the armholes of his vest, then he dropped them in front of him when Courtright said, ‘You needn’t be getting out your gun.’ Luke said, ‘I haven’t got any gun here, Jim’ and raised up his vest to show him. Courtright then pulled his pistol. He drew it first, and then Short drew his and commenced to fire.”

Jim Courtright, the famed fast-draw gunfighter, never got off a shot. Some historians theorize that Courtright’s gun jammed or that the hammer of his pistol snagged his watch chain (was that chain fastened to the watch that Jake Johnson had given to Courtright?). Otherwise, those historians ponder, how could anyone, even Luke Short, have outdrawn Courright, who, the Gazette said, was deadly accurate with either hand and “as quick as lightning”? “In a desperate emergency his coolness and self-possession never left him.”

Jim Courtright, the famed fast-draw gunfighter, never got off a shot. Some historians theorize that Courtright’s gun jammed or that the hammer of his pistol snagged his watch chain (was that chain fastened to the watch that Jake Johnson had given to Courtright?). Otherwise, those historians ponder, how could anyone, even Luke Short, have outdrawn Courright, who, the Gazette said, was deadly accurate with either hand and “as quick as lightning”? “In a desperate emergency his coolness and self-possession never left him.”

And yet there he was—dead on the floor of a shooting gallery. Short’s first shot had been fired at close range. Courtright fell into the entrance of the shooting gallery, his boots on the sidewalk, his .45 still in his hand. Short fired four more times.

Police officer J. J. Fulford quickly arrived at the scene. He bent over Courtright. Fulford later testified that Courtright’s last words were “Ful, they’ve got me.”

Like Fulford, police officer William Bonaparte (“Bony”) Tucker Jr. was quick to arrive at the scene of the shooting, having been standing at the corner of 3rd and Main streets when a man rushed up and warned Tucker that “there was going to be trouble between Jim Courtright and Luke Short.” Soon after, Tucker recalled, “the crack of a pistol rang out.” As Tucker ran north he heard four more shots. By the time he reached the shooting gallery, Courtright was too weak to speak.

Tucker told the Gazette that Courtright “grasped his gun in one hand, a ‘45’ of the same make as the one that killed him. The chambers were full of cartridges, showing that he had failed to get in a shot. Three bullets had taken effect. One broke his right thumb, the second passed through his heart and the third struck him in the right shoulder. . . . He was a dead man within five minutes after I reached him.”

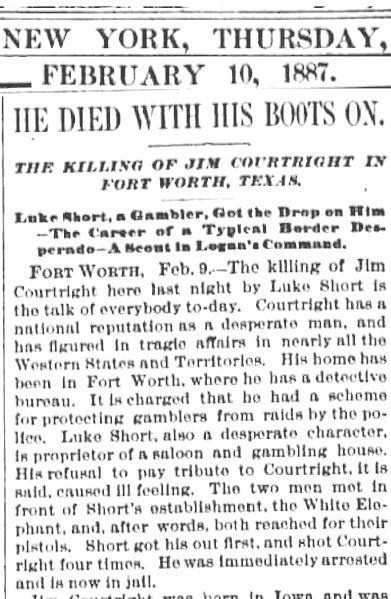

“HE DIED WITH HIS BOOTS ON”: The one-sided “shootout” made headlines around the country, including page 1 of the New York Sun. This report alludes to Courtright’s protection racket, Short’s refusal to pay “tribute,” and the resultant “ill feeling.”

“HE DIED WITH HIS BOOTS ON”: The one-sided “shootout” made headlines around the country, including page 1 of the New York Sun. This report alludes to Courtright’s protection racket, Short’s refusal to pay “tribute,” and the resultant “ill feeling.”

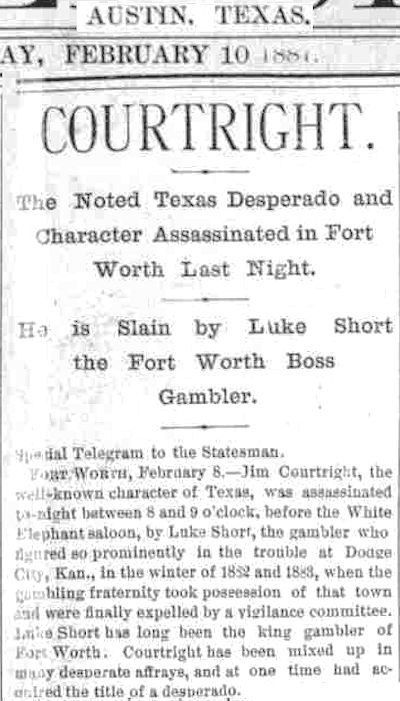

Page 1 of the Austin Weekly Statesman.

Page 1 of the Austin Weekly Statesman.

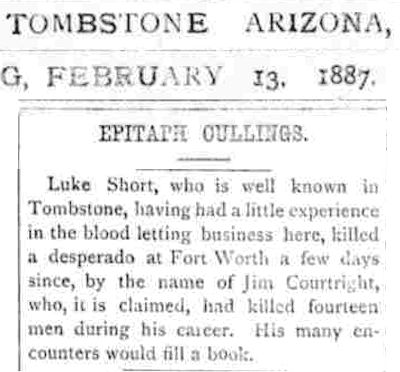

The Tombstone Epitaph on February 13. Luke Short had killed Charlie Storms in Tombstone.

The Tombstone Epitaph on February 13. Luke Short had killed Charlie Storms in Tombstone.

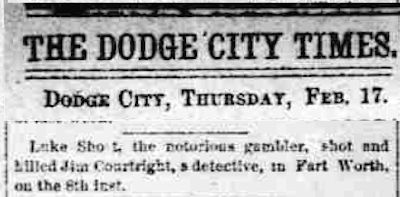

And, of course, the Dodge City Times of February 17. Short (and Bat Masterson) had been a member of the Dodge City Peace Commission.

And, of course, the Dodge City Times of February 17. Short (and Bat Masterson) had been a member of the Dodge City Peace Commission.

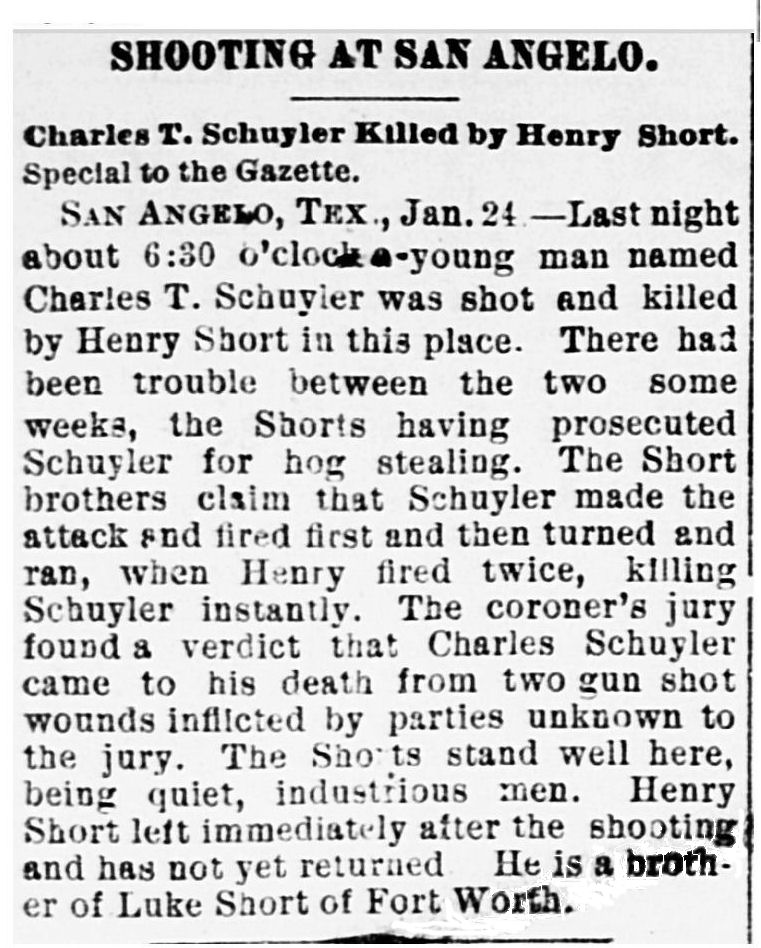

Luke was not the only Short boy weathering a stormy patch of time in 1887. In San Angelo just two weeks earlier, brother Henry had shot and killed a man.

Luke was not the only Short boy weathering a stormy patch of time in 1887. In San Angelo just two weeks earlier, brother Henry had shot and killed a man.

Henry was five years younger than Luke.

Henry was five years younger than Luke.

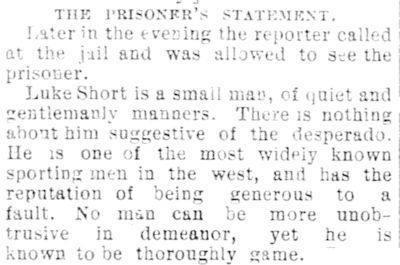

As for Luke Short, held in a county jail cell after the Courtright shooting, Short corroborated the account told by witness Jake Johnson. Short “very calmly” told a Gazette reporter: “Of course, it is an affair to be regretted. If I felt that I was in the wrong, I wouldn’t like to talk about it, but as I wasn’t, there isn’t any reason to refrain from telling how it happened. In the first place I want to say that it was all sudden, all unexpected by me. There had been no previous disagreement between us. Early in the evening I was getting my shoes blackened at the White Elephant, when a friend of mine asked me if there was any trouble between Courtright and myself, and I told him there was nothing. A few minutes later I was at the bar with a couple of friends when someone called me. I went out into the vestibule and saw Jim Courtright and Jake Johnson. . . . I walked out with them upon the sidewalk. . . . I reminded him [Courtright] of some past transactions, not in an abusive or reproachful manner, to which he assented, but not in a very cordial way. I was standing with my thumbs in the armholes of my vest and had dropped them in front of me to adjust my clothing, when he remarked: ‘Well, you needn’t reach for your gun’ and immediately put his hand to his hip pocket and pulled his. When I saw him do that, I pulled my pistol from my hip pocket, too, and began shooting, for I knew that his action meant death.”

(Bat Masterson’s friend Alfred Henry Lewis in 1907 wrote that after the shooting Masterson had persuaded Tarrant County Sheriff Ben Shipp to allow Masterson, armed with two six-shooters, to spend the night in Short’s jail cell because of fear that a mob would try to remove Short from his jail cell and lynch him. I have not found that claim corroborated in newspaper accounts of 1887.)

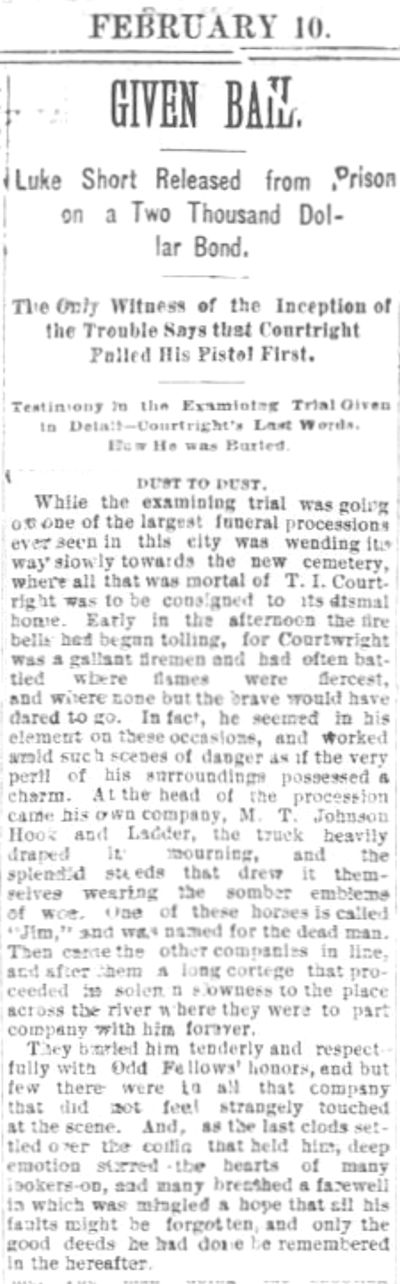

As for Jim Courtright, he was given “one of the largest funeral processions ever seen in this city,” led by his M. T. Johnson hook-and-ladder volunteer fire company (one of the horses was named “Jim” in his honor). Courtright was buried “tenderly and respectfully” with Odd Fellows honors at the “new cemetery” (Oakwood).

As for Jim Courtright, he was given “one of the largest funeral processions ever seen in this city,” led by his M. T. Johnson hook-and-ladder volunteer fire company (one of the horses was named “Jim” in his honor). Courtright was buried “tenderly and respectfully” with Odd Fellows honors at the “new cemetery” (Oakwood).

As for Luke Short, among the Fort Worth residents signing his bail bond were Jake Johnson, Walter T. Maddox (former sheriff and brother of James and Robert), and attorney Robert McCart (namesake of the South Side street). Short at his examining trial was represented by McCart and William Capps, who in 1884 had helped to defuse a volatile incident involving Jim Courtright.

One witness at the examining trial, W. A. James, testified that on the night before the shooting he had heard Courtright say “that there was a combination against him over the White Elephant,” “that he hadn’t been treated with respect upstairs over the White Elephant.” The saloon’s gambling room was located upstairs over the bar.

James testified that Courtright said “God had made one man superior to another in muscular power, but when Colt made his pistol, that made all men equal.” James again quoted Courtright: “Courtright said he had lived over his time. No man on earth, he said, had a percentage over him. He said that this would be settled within a week.”

Luke Short was not tried for the killing of Jim Courtright. In those days, when one armed man killed another armed man, a charge of murder was rare unless the victim was shot in the back.

Luke Short was a free man.

(Muddying the motives, Courtright biographer Father Stanley Crocchiola in his Longhair Jim Courtright wrote that Luke Short was in love with Courtright’s wife Betty: “Immediately following Courtright’s funeral, Short made repeated efforts to induce the widow to marry him, using as an excuse his regrets that he made her a widow. . . . She ran him off with a shotgun.”)

Luke Short lived only another six years. Luke Short died in 1893. At age thirty-nine. Of natural causes.

Luke Short is buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

Jim Courtright also is buried in Oakwood Cemetery. Short is buried in section 20. Courtright is buried in section 27, well out of pistol range.

Jim Courtright also is buried in Oakwood Cemetery. Short is buried in section 20. Courtright is buried in section 27, well out of pistol range.

His headstone, erected by a granddaughter in 1954, reads:

“Jim ‘Longhaired’ Courtright

1845-1887

U.S. Army scout, U.S. marshal [he was a city marshal but only a deputy U.S. marshal], frontiersman, pioneer, representative of a class of men now passing from Texas, who, whatever their faults, were the type of that brave, courageous manhood which commands respect and admiration.”

When gambler and gunfighter Timothy Isaiah Courtright died he was forty-two years old. Young for a gambler, old for a gunfighter.

Posts About Fort Worth’s Wild West History

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade

Good read. Only thing was his birth date not the 22nd of January?

The same Courtright who owned the Pantherosa?

Meow.

Excellent story…again. I regularly tell others that this was one of the last such “Main Street” type gunfights known. No matter what the movies show, I have read that they were actually rare. There were such characters as these in the days before law and order prevailed.

Thanks, Darrell. I wonder what Short and Courtright would think about their ongoing fame all these years later.

There is a not-well-written book about Courtright by Father Stanley Crocchiola, 1957, “Longhair Jim Courtright Two Gun Marshall of Fort Worth,” that my father was happy to read two or three times a year….Don’t know what his attraction to the story was….Of course, 1957 tomes are out of print, but Amazon or Ebay probably have some….Interesting use of “the Fort” as a descriptor of the town, same as the clips you have….Crocchiola’s book is mostly reprints of newspaper accounts

Thanks, Dan. Just found it at Abe for six bucks. Crocchiola wrote a LOT of such books. Yeah, the Dallas papers routinely referred to Fort Worth as “the Fort.”