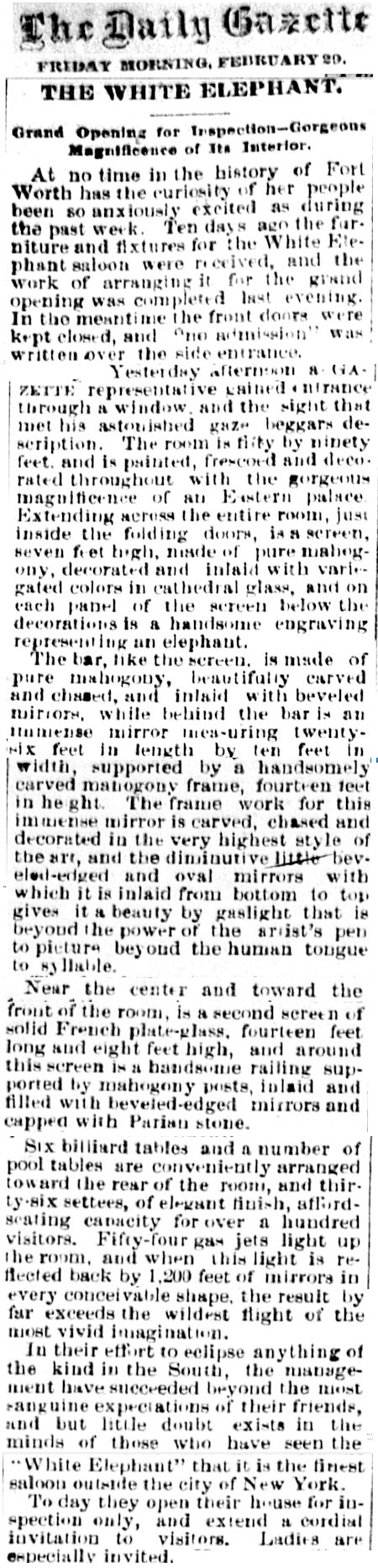

On February 28, 1884 an intrepid reporter for the Fort Worth Daily Gazette climbed through a window to gain access to the White Elephant Saloon to have a look-see before the new saloon formally opened to the public.

On February 29 the Gazette revealed to the public what the reporter saw: “The sight that met his astonished gaze beggars description,” the Gazette swooned: “the gorgeous magnificence of an Eastern palace,” “exceeds the wildest flight of the most vivid imagination,” “finest saloon outside the city of New York.”

Also on February 29—Leap Day—the White Elephant held an open house prior to the formal opening March 1. “Ladies are especially invited.”

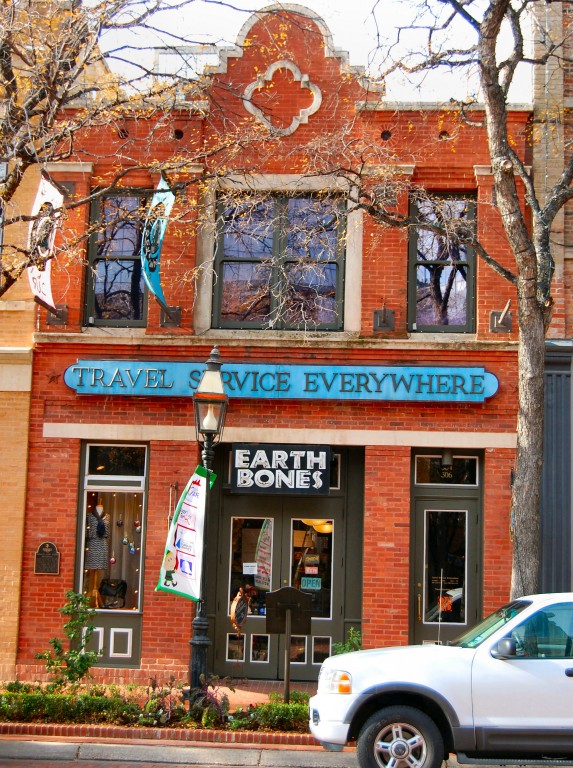

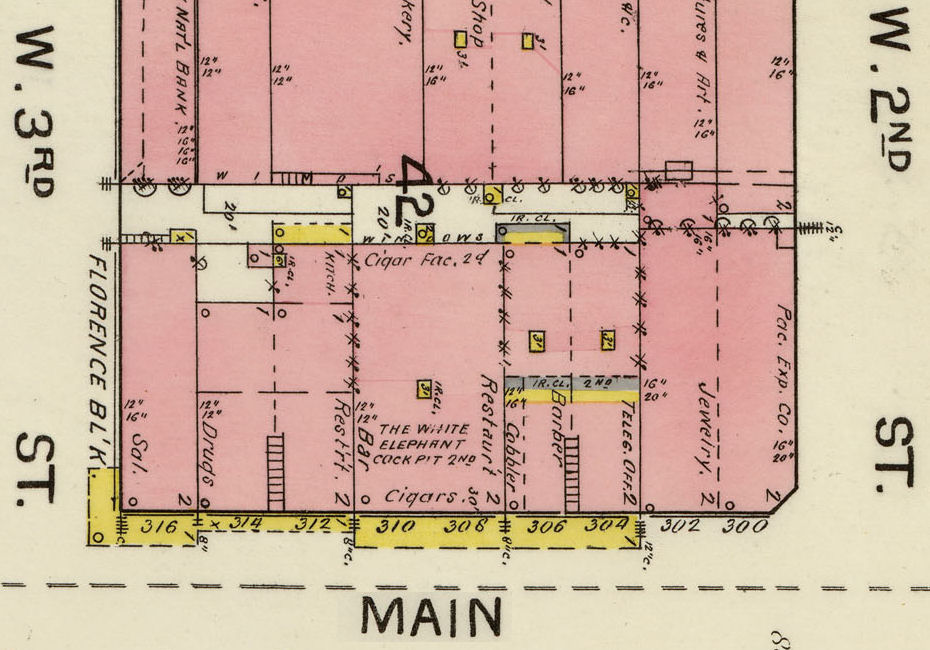

Fort Worth’s White Elephant Saloon was located at 308 Main Street, where the Morris Building (1906) stands today. (The circa-1976 White Elephant Saloon at the Stockyards is an in-name-only incarnation.)

Fort Worth’s White Elephant Saloon was located at 308 Main Street, where the Morris Building (1906) stands today. (The circa-1976 White Elephant Saloon at the Stockyards is an in-name-only incarnation.)

The Gazette described the new saloon as “the most gorgeously gotten-up affair of the kind in the state.” Downstairs it had a forty-foot-long bar of mahogany and onyx. Cut-glass chandeliers, gas light. The best food, drink, and smokes. Upstairs it had tables for gambling (faro, keno, monte, roulette, poker). Honest gambling. With big stakes. And big names.

For example, one poker game at the White Elephant drew a veritable who’s who of gamblers in August 1885. According to gambler Charles Coe in My Life as a Card Shark, sitting around the poker table were Coe, Luke Short, Jim Courtright, Wyatt Earp, and Bat Masterson. (Short, Earp, and Masterson had been three-eighths of the Dodge City Peace Commission.) At the end of the night, Coe was on top of the heap.

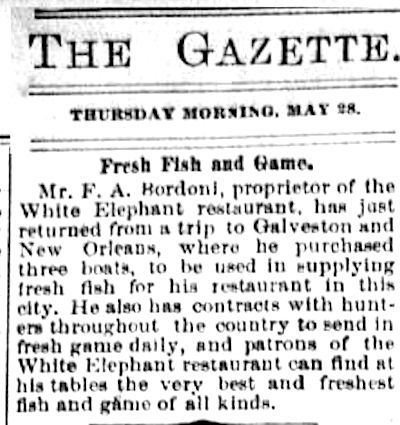

On May 28 the Gazette reported that the proprietor, Frenchman F. A. Borodino, had bought three boats to supply the White Elephant with fresh fish and that he had contracts with hunters for fresh game.

On May 28 the Gazette reported that the proprietor, Frenchman F. A. Borodino, had bought three boats to supply the White Elephant with fresh fish and that he had contracts with hunters for fresh game.

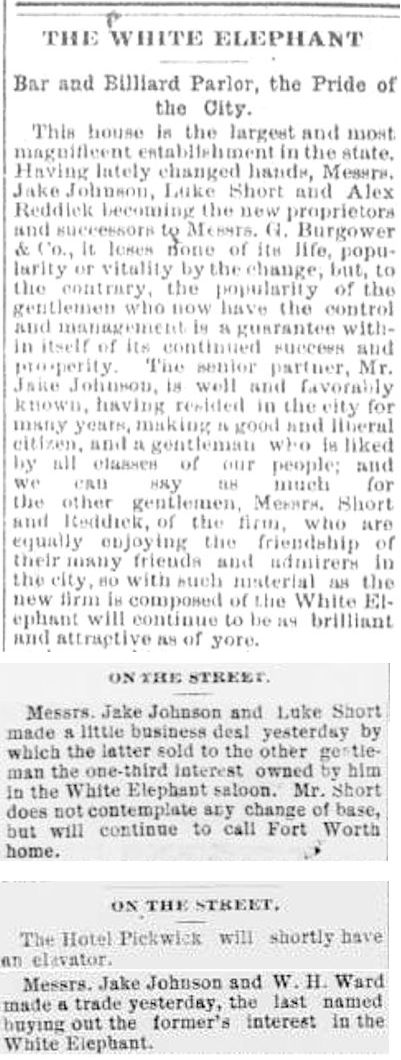

Perhaps Borodino overextended himself, because profits were disappointing, and the saloon closed in a few months. It was reopened later in 1884 by new owners Burgower, Bornstein, and Sam Berliner, a partner in the White Elephant Saloon in San Antonio. But soon gambler Jake Johnson and Luke Short, along with Alex Reddick, bought the saloon from Burgower, Bornstein, and Berliner. On February 7, 1887, one day before Short killed Courtright, Short sold his one-third interest in the saloon to Johnson. Nine days later Johnson “flipped” his share of the saloon to Bill Ward, who was an alderman and owner of the Fort Worth Panthers baseball club. Clips are from the December 21, 1884 and February 8 and February 17, 1887 Fort Worth Gazette.

Perhaps Borodino overextended himself, because profits were disappointing, and the saloon closed in a few months. It was reopened later in 1884 by new owners Burgower, Bornstein, and Sam Berliner, a partner in the White Elephant Saloon in San Antonio. But soon gambler Jake Johnson and Luke Short, along with Alex Reddick, bought the saloon from Burgower, Bornstein, and Berliner. On February 7, 1887, one day before Short killed Courtright, Short sold his one-third interest in the saloon to Johnson. Nine days later Johnson “flipped” his share of the saloon to Bill Ward, who was an alderman and owner of the Fort Worth Panthers baseball club. Clips are from the December 21, 1884 and February 8 and February 17, 1887 Fort Worth Gazette.

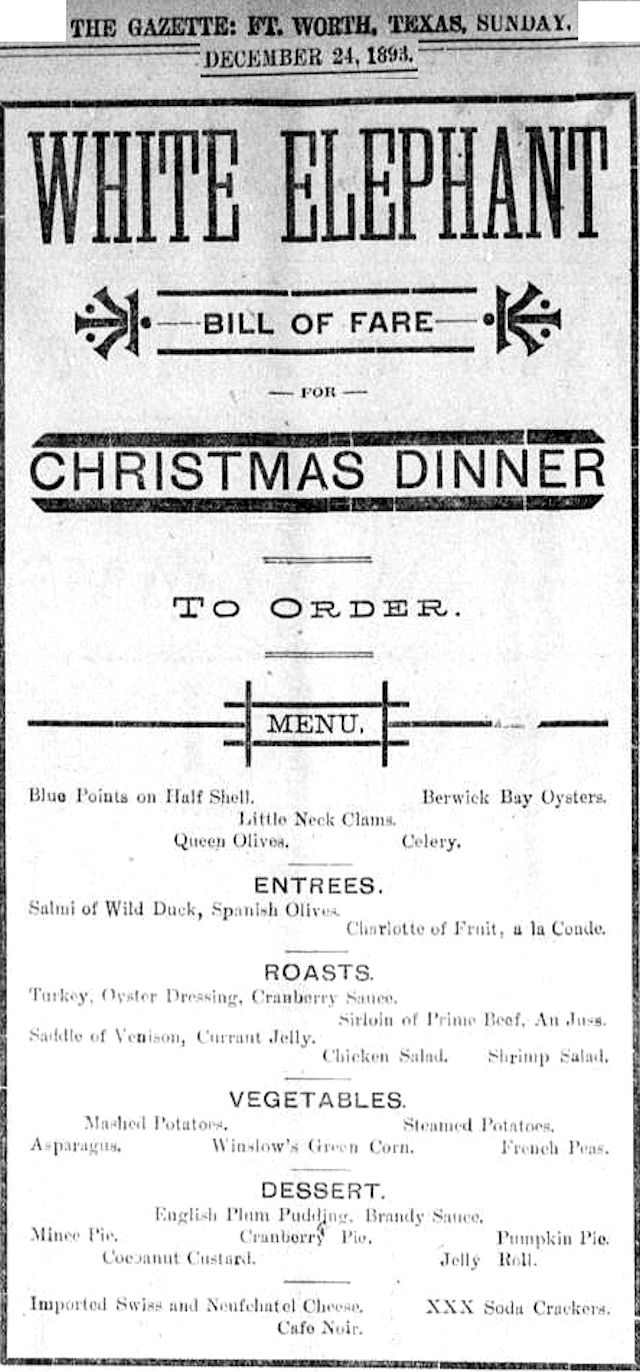

The White Elephant flourished under Bill Ward and his brother John. By the time this Christmas menu of the White Elephant was printed in 1893, the White Elephant was on solid financial footing and living up to its early hype.

The White Elephant flourished under Bill Ward and his brother John. By the time this Christmas menu of the White Elephant was printed in 1893, the White Elephant was on solid financial footing and living up to its early hype.

Oh sure, now and then a pistol was drawn or a punch thrown, but in terms of gentility, the White Elephant was first class. None of your Hell’s Half Acre riff-raff rowdies here.

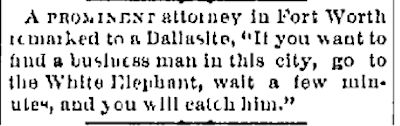

The Dallas Weekly Herald on January 22, 1885 indicated that the White Elephant was a favorite of Fort Worth businessmen.

The Dallas Weekly Herald on January 22, 1885 indicated that the White Elephant was a favorite of Fort Worth businessmen.

Blood sports, seances, Judas Iscariot’s pocket change—the White Elephant was certainly eclectic. As the bottom news brief shows, sometimes there was even a floor show. Music historian John Lomax even used the White Elephant (in its second incarnation; see below) as a recording studio for old-timers of the Chisholm Trail cattle drives. In the 1940s Lomax recalled: “In 1909 I went to the Cattlemen’s Convention in Fort Worth, Texas. One night I found myself in the back room of the White Elephant Saloon. I carried with me a small Edison recording machine that used wax cylinders. Instead of a microphone, I used a big horn, which the cowboys usually refused to sing into.”

Blood sports, seances, Judas Iscariot’s pocket change—the White Elephant was certainly eclectic. As the bottom news brief shows, sometimes there was even a floor show. Music historian John Lomax even used the White Elephant (in its second incarnation; see below) as a recording studio for old-timers of the Chisholm Trail cattle drives. In the 1940s Lomax recalled: “In 1909 I went to the Cattlemen’s Convention in Fort Worth, Texas. One night I found myself in the back room of the White Elephant Saloon. I carried with me a small Edison recording machine that used wax cylinders. Instead of a microphone, I used a big horn, which the cowboys usually refused to sing into.”

Saloons (and other businesses) often gave tokens to customers in lieu of money as change because tokens (1) served as advertising for the businesses and (2) motivated customers to return to the businesses. (Image courtesy of Jerry Adams.)

Saloons (and other businesses) often gave tokens to customers in lieu of money as change because tokens (1) served as advertising for the businesses and (2) motivated customers to return to the businesses. (Image courtesy of Jerry Adams.)

As the White Elephant prospered, it outgrew its building and relocated. Just as well: As the Gazette clip of November 1899 shows, the old building did not make it into the new century.

As the White Elephant prospered, it outgrew its building and relocated. Just as well: As the Gazette clip of November 1899 shows, the old building did not make it into the new century.

In 1896 the White Elephant reopened three blocks south, in the Winfree Building (1890) at 604-610 Main. (The little two-story Winfree Building is tucked between the Ashton Hotel and the Kress Building.) The new White Elephant still had a saloon with a forty-foot bar and a gambling casino. But now the gambling went on across the country as well as across the table: Men gambled on horse races, prizefights, and ballgames from all over the country as the telegraph hookup brought in the latest results. The new location was modern, strictly twentieth century: electric lights and telephones. Even indoor plumbing.

In 1896 the White Elephant reopened three blocks south, in the Winfree Building (1890) at 604-610 Main. (The little two-story Winfree Building is tucked between the Ashton Hotel and the Kress Building.) The new White Elephant still had a saloon with a forty-foot bar and a gambling casino. But now the gambling went on across the country as well as across the table: Men gambled on horse races, prizefights, and ballgames from all over the country as the telegraph hookup brought in the latest results. The new location was modern, strictly twentieth century: electric lights and telephones. Even indoor plumbing.

Owner Bill Ward improved the quality of the food and introduced family dining. This city directory ad is from 1896.

Owner Bill Ward improved the quality of the food and introduced family dining. This city directory ad is from 1896.

This ad is from the January 16, 1897 Fort Worth Register.

This ad is from the January 16, 1897 Fort Worth Register.

But perhaps Ward, like original owner Borodino, overextended himself.

The day in 1901 when the White Elephant did not open was big news in the February 26 Register. Ward was deeply in debt to suppliers and employees. He owed back rent to building owner Winfield Scott (he of Thistle Hill). That 1901 news story shows how much Fort Worth had outgrown its wild West past. The Register wrote that “in the old days” (at most seventeen years earlier!) “when every man carried a gun, and to be expert with the trigger was to be the best man, it [the White Elephant] was the rendezvous where many of the old-timers congregated.”

The day in 1901 when the White Elephant did not open was big news in the February 26 Register. Ward was deeply in debt to suppliers and employees. He owed back rent to building owner Winfield Scott (he of Thistle Hill). That 1901 news story shows how much Fort Worth had outgrown its wild West past. The Register wrote that “in the old days” (at most seventeen years earlier!) “when every man carried a gun, and to be expert with the trigger was to be the best man, it [the White Elephant] was the rendezvous where many of the old-timers congregated.”

The White Elephant reopened, but it underwent more changes. Owners came and went. Anti-gambling and anti-saloon sentiments were growing. Finally, about 1915 “last call” came for the White Elephant, once “the most gorgeously gotten-up affair of the kind in the state.”

Wow, so informative. My family has been here since the 1850s and I always loved the history of this city. Thank you so much for sharing your research.

Thank you, Amanda.

Mike…your web is absolutely wonderful…pictures, pictures and more pictures…AMAZING.

Clara

Thanks, Clara. You are that rare kind of person I write Hometown for: a historyhead. Thanks for your own contribution to Cowtown history research.