The cause was a fleeting “boys will be boys” lark; the effect was permanent changes in the way Fort Worth prepares for disasters.

Two boys experimenting with cigarettes and matches near the intersection of St. Louis and Peter Smith streets started the great South Side fire of April 3, 1909. First a nearby barn went up in flames. The fire quickly jumped to another building. And another. Within minutes the fire, fed by wood-framed, wood-shingled houses and winds gusting to forty miles per hour, was spreading to the north, toward downtown with what the Star-Telegram called “uncontrollable fury.”

Two boys experimenting with cigarettes and matches near the intersection of St. Louis and Peter Smith streets started the great South Side fire of April 3, 1909. First a nearby barn went up in flames. The fire quickly jumped to another building. And another. Within minutes the fire, fed by wood-framed, wood-shingled houses and winds gusting to forty miles per hour, was spreading to the north, toward downtown with what the Star-Telegram called “uncontrollable fury.”

All of Fort Worth’s fire companies were dispatched to the fire, as were companies from Dallas, who arrived by train even as Dallas on that day battled its own major fire in Oak Cliff. Fire companies from Weatherford and the city of North Fort Worth also helped Fort Worth.

The Fort Worth Panthers and Detroit Tigers even canceled their exhibition baseball game that day and helped fight the fire.

The Fort Worth Panthers and Detroit Tigers even canceled their exhibition baseball game that day and helped fight the fire.

The wooden Jennings Avenue viaduct was gridlocked with delivery wagons trying to reach the fire zone to haul personal belongings from threatened houses. Husbands and fathers evacuated their families to a makeshift refugee camp on the Texas & Pacific reservation along Vickery Boulevard. There family members huddled around sad piles of silverware, family Bibles, heirlooms, and other prized possessions as the men returned to the fire zone to help firefighters.

The Fort Worth fire department, still using horse-drawn equipment, was not prepared for such a conflagration. “Helpless,” the Star-Telegram said in its first report. The fire melted the copper wires of the fire department’s alarm telegraph. The fire melted fire hoses. The streetcar lines lost electricity for about three hours. Telephone service was disrupted.

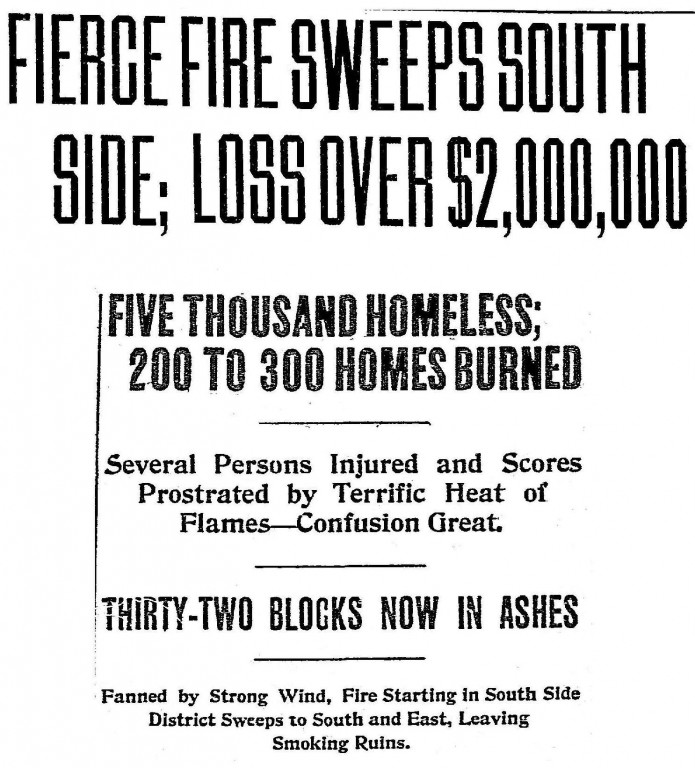

This retrospective map in the July 2, 1922 Star-Telegram shows the burned area.

This retrospective map in the July 2, 1922 Star-Telegram shows the burned area.

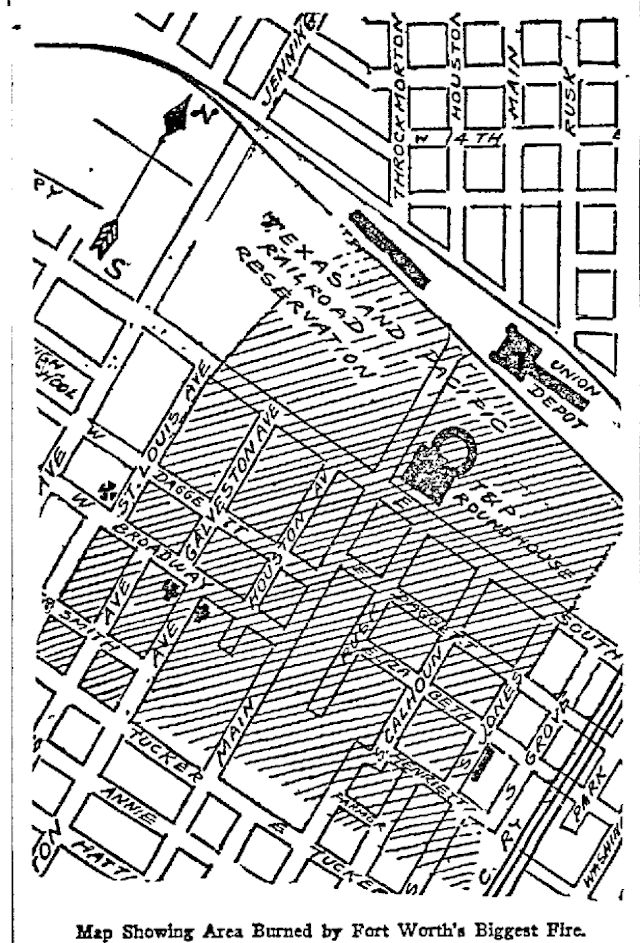

After three hours, the voracious fire simply ran out of fuel and burned itself out. Much of the near South Side was reduced to a black forest of charred posts and brick chimneys. The aerial photo shows the burn zone today. The yellow circle is the intersection of St. Louis and Peter Smith streets. The blue circle in the upper right shows the location of . . .

After three hours, the voracious fire simply ran out of fuel and burned itself out. Much of the near South Side was reduced to a black forest of charred posts and brick chimneys. The aerial photo shows the burn zone today. The yellow circle is the intersection of St. Louis and Peter Smith streets. The blue circle in the upper right shows the location of . . .

the Missouri-Kansas-Texas (Katy) railroad freight terminal on Vickery Boulevard, built in 1908. It is said to have been one of the few structures left standing in the burn zone.

This photo of South Main Street shows the “clean sweep” of destruction from Tucker Street north to the Texas & Pacific passenger depot (clock tower visible). (Photo from DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University.)

This photo of South Main Street shows the “clean sweep” of destruction from Tucker Street north to the Texas & Pacific passenger depot (clock tower visible). (Photo from DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University.)

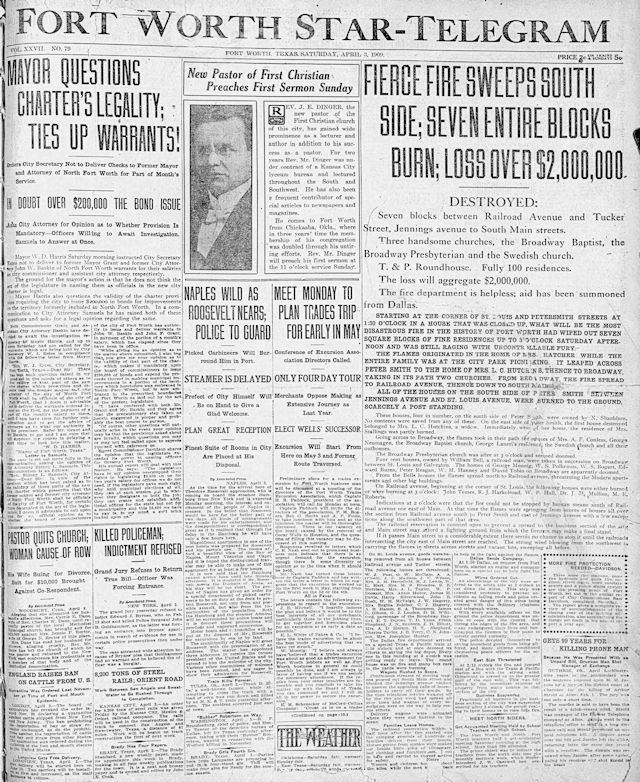

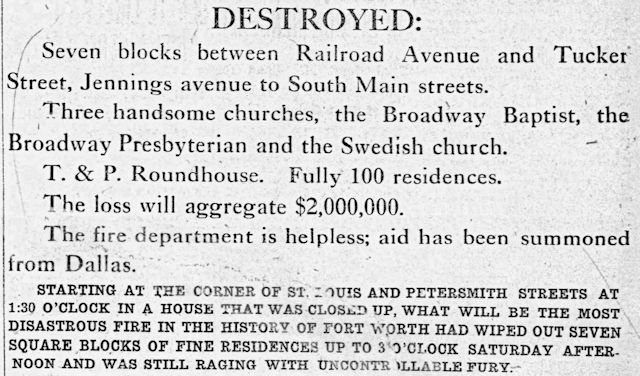

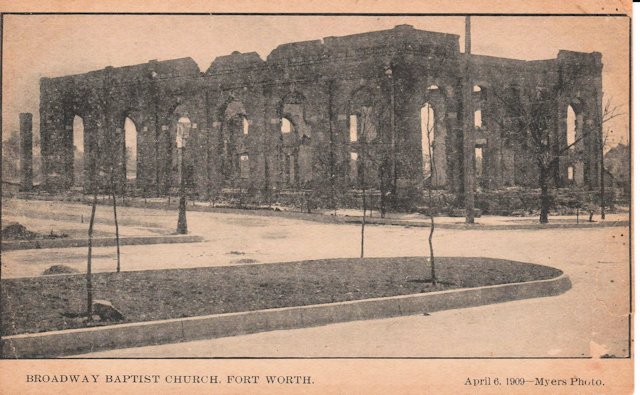

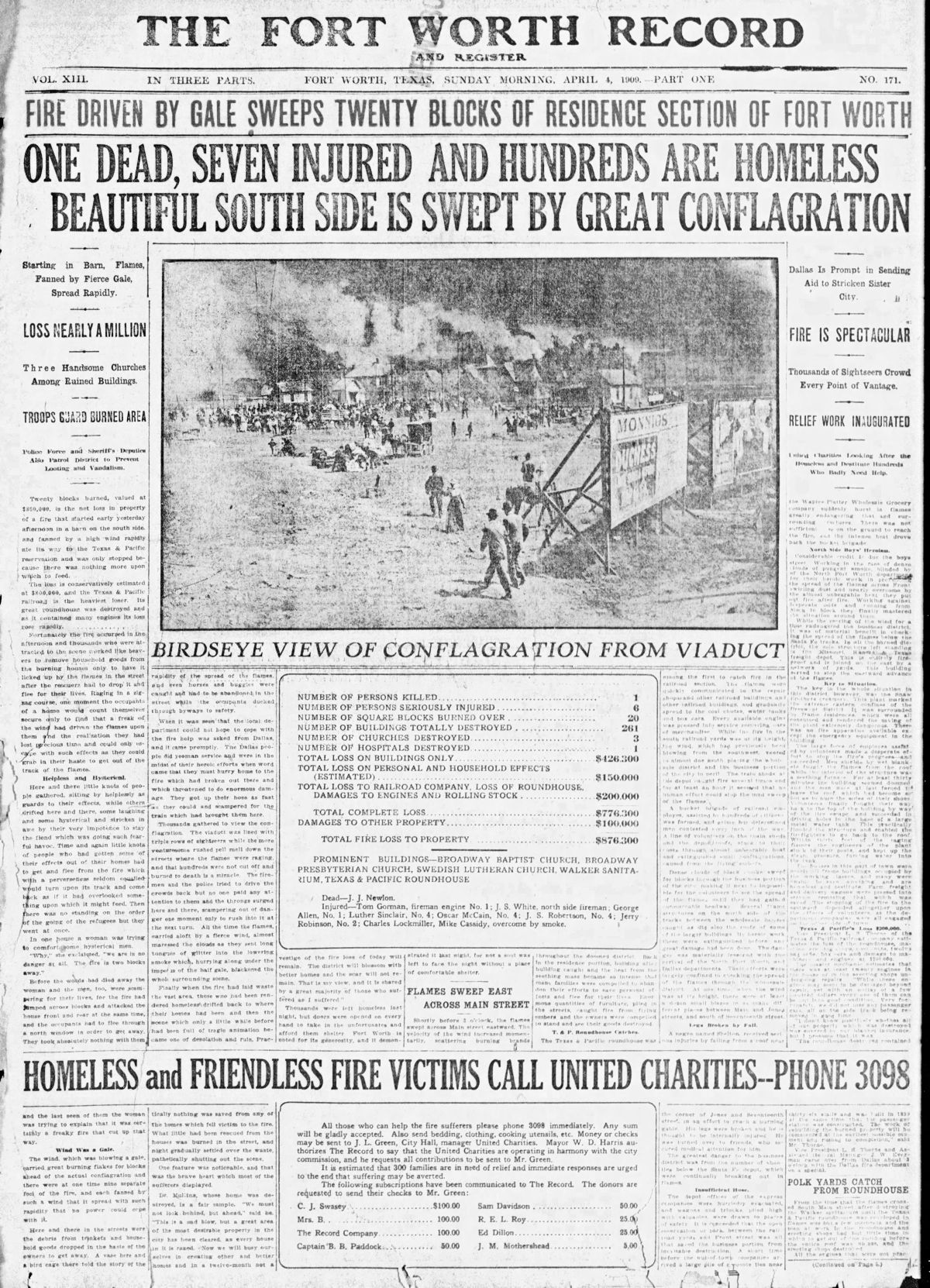

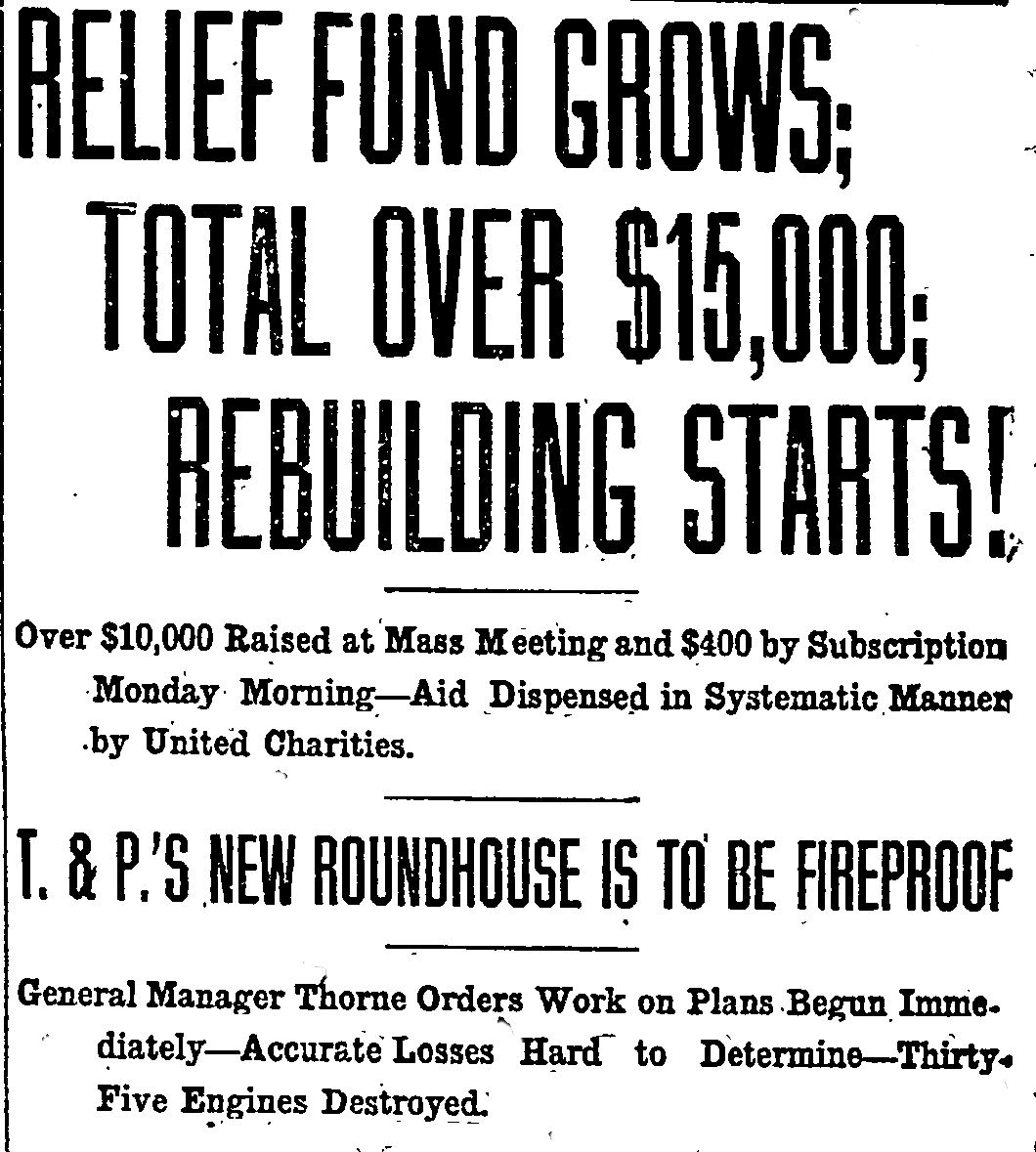

The early headlines show the scope of devastation. Among the buildings destroyed were one hundred residences and three churches (Broadway Baptist, Broadway Presbyterian, and Swedish Methodist Episcopal). The $2 million in estimated damage would be $44 million today.

The early headlines show the scope of devastation. Among the buildings destroyed were one hundred residences and three churches (Broadway Baptist, Broadway Presbyterian, and Swedish Methodist Episcopal). The $2 million in estimated damage would be $44 million today.

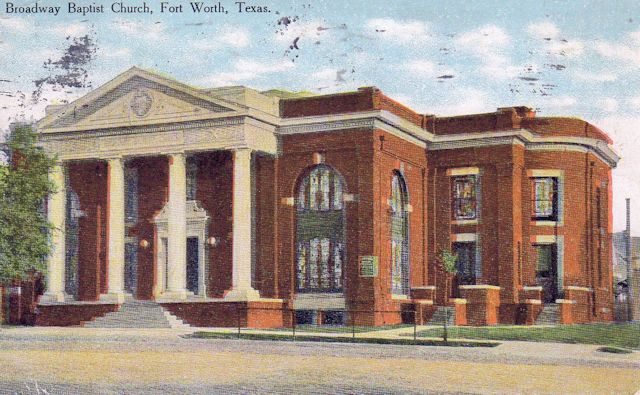

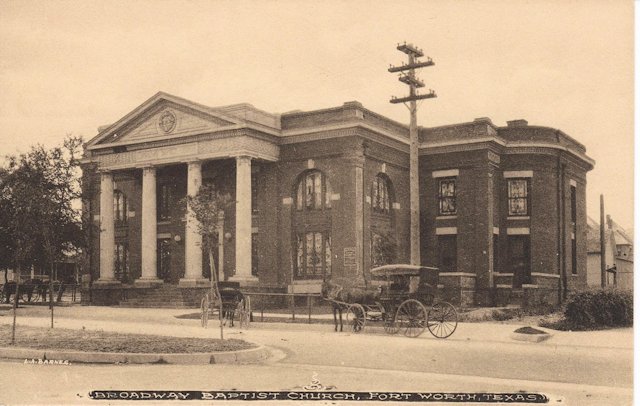

Members of Broadway Baptist Church had worshipped in a wood-frame building until May 1906, when members dedicated their $25,000 Sanguinet and Staats gem. Three years later it was in ruins. (Images courtesy of Barbara Love Logan.)

Members of Broadway Baptist Church had worshipped in a wood-frame building until May 1906, when members dedicated their $25,000 Sanguinet and Staats gem. Three years later it was in ruins. (Images courtesy of Barbara Love Logan.)

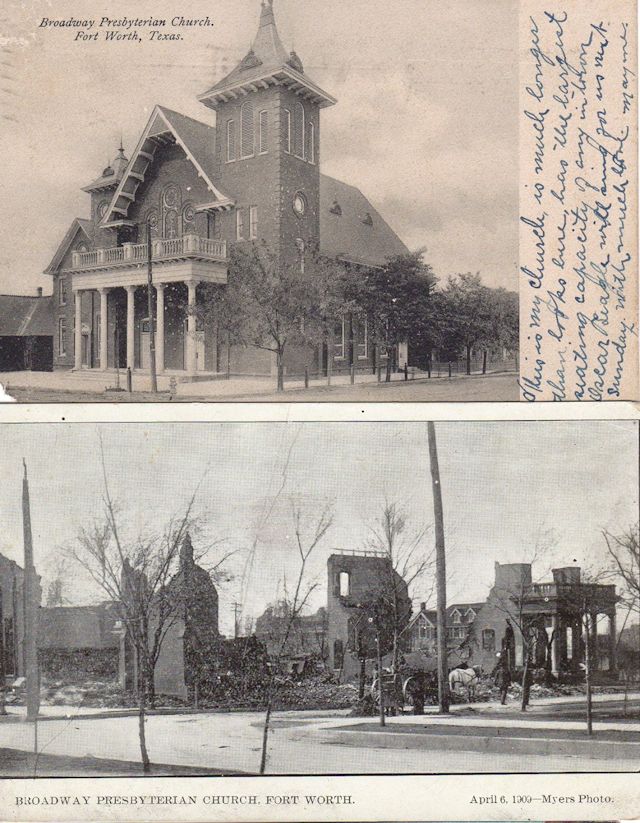

The Broadway Presbyterian Church building (1901) before and after. The building was located just north of Broadway Baptist Church. (Postcards courtesy of Barbara Love Logan.)

The Broadway Presbyterian Church building (1901) before and after. The building was located just north of Broadway Baptist Church. (Postcards courtesy of Barbara Love Logan.)

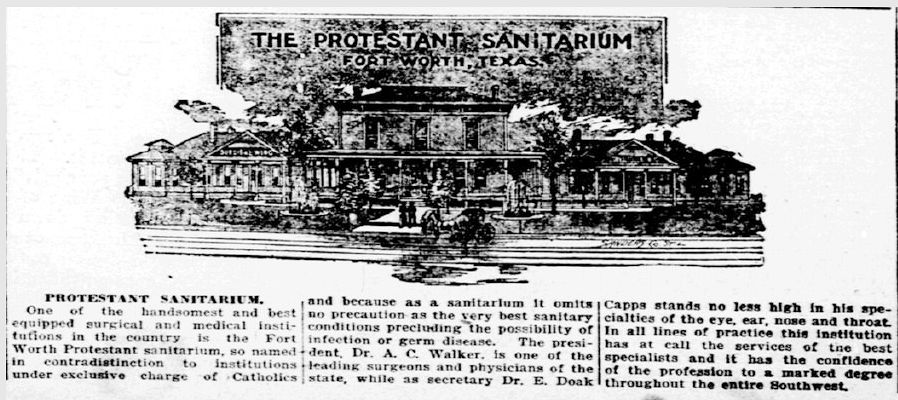

Also burned was the Protestant Sanitarium at South Main and Railroad Avenue (Vickery Boulevard).

Also burned was the Protestant Sanitarium at South Main and Railroad Avenue (Vickery Boulevard).

The front page of the Fort Worth Record.

The front page of the Fort Worth Record.

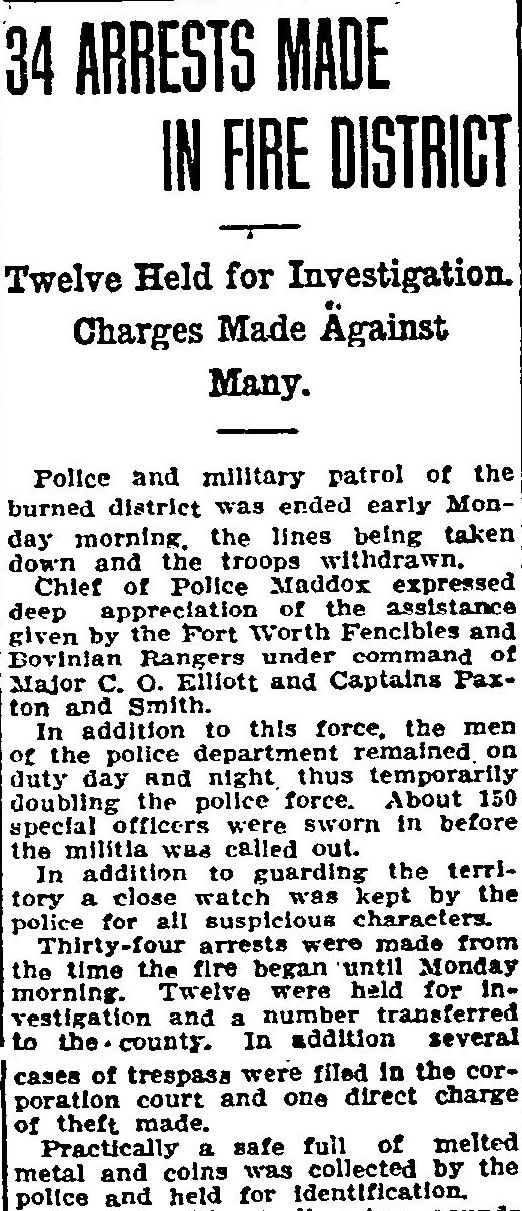

The burn zone was patrolled; by April 5 thirty-four people had been arrested. (The Fort Worth Fencibles and Bovinian Rangers were local militia units.)

The burn zone was patrolled; by April 5 thirty-four people had been arrested. (The Fort Worth Fencibles and Bovinian Rangers were local militia units.)

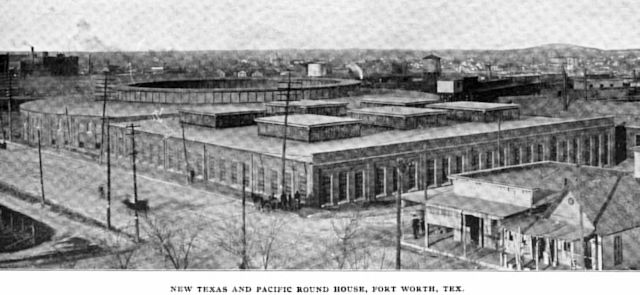

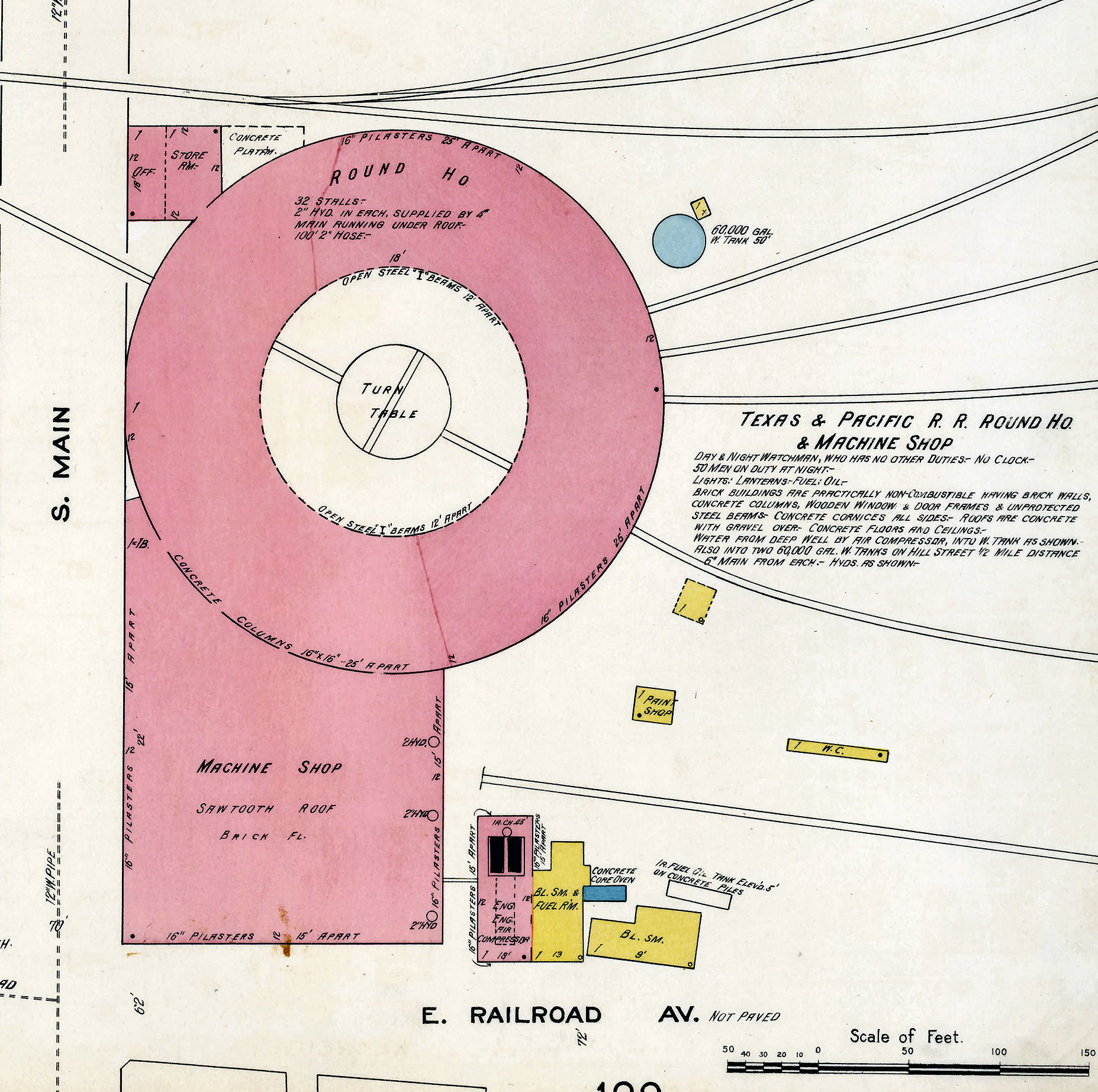

While Fort Worth counted its losses, it could also count its blessings: The fire could have been even worse. The sprawling Texas & Pacific railroad reservation along today’s Vickery Boulevard acted as a fire break, keeping the fire from spreading farther north to downtown. But T&P was the biggest monetary loser of the fire. Some of its workshops, freight cars, its roundhouse, and thirty-five locomotives inside the roundhouse were burned. Coal in the train yard burned, adding to the black smoke filling the sky.

While Fort Worth counted its losses, it could also count its blessings: The fire could have been even worse. The sprawling Texas & Pacific railroad reservation along today’s Vickery Boulevard acted as a fire break, keeping the fire from spreading farther north to downtown. But T&P was the biggest monetary loser of the fire. Some of its workshops, freight cars, its roundhouse, and thirty-five locomotives inside the roundhouse were burned. Coal in the train yard burned, adding to the black smoke filling the sky.

The fire spared Fort Worth High School, one block west of Broadway Baptist Church, but the school building would burn a year later.

Fort Worth began relief and reconstruction immediately.

Fort Worth began relief and reconstruction immediately.

The roundhouse and adjacent machine shops had been built in 1899 as the passenger depot was built.

The roundhouse and adjacent machine shops had been built in 1899 as the passenger depot was built.

This 1911 Sanborn map shows Texas & Pacific’s new roundhouse at Main and Railroad Avenue (Vickery Boulevard).

The wind that had spread the fire would prove true the “ill wind” proverb: Because of the fire, Fort Worth made changes for the better.

The fire department had pumped so much water onto the fire that the city water supply had been compromised. In response, in 1913 the city would build Lake Worth as a reservoir to provide more water for such emergencies.

The fire department had pumped so much water onto the fire that the city water supply had been compromised. In response, in 1913 the city would build Lake Worth as a reservoir to provide more water for such emergencies.

The fire department bought hoses that would not melt in intense heat. It bought motorized vehicles and built more neighborhood fire stations, such as the Bryan Street station (1911) just four blocks east of where the fire began. This station replaced an earlier station. The city paved more streets and encouraged people to build brick “fireproof” homes in place of the wooden houses that had burned so easily in 1909.

The fire department bought hoses that would not melt in intense heat. It bought motorized vehicles and built more neighborhood fire stations, such as the Bryan Street station (1911) just four blocks east of where the fire began. This station replaced an earlier station. The city paved more streets and encouraged people to build brick “fireproof” homes in place of the wooden houses that had burned so easily in 1909.

And today a fire hydrant stands at the corner where the great South Side fire began.

And today a fire hydrant stands at the corner where the great South Side fire began.

Despite the scope of the fire, just as British-born Al Hayne had been the only fatality of the Texas Spring Palace fire of 1890, J. J. Newlon, a banker from Krum, was the only fatality of the great South Side fire of 1909. Newlon, who was visiting friends on West Daggett Street, died as he was helping save valuables from the fire.

Footnote: Seven of Fort Worth’s early fires (four of them on railroad property) occurred in the area between Lancaster Avenue and Hattie Street south of downtown: Spring Palace (1890), 1882 T&P passenger depot (1896), 1899 T&P passenger depot (1904), Fifth Ward school and Missouri Avenue Methodist Church (1904), 1902 T&P freight depot (1908), South Side (1909), Fort Worth High School (1910).

As a retired teacher I shared this article about the history of Fort Worth every year that I taught. I usually waited ‘till a windy day in April so that I could emulate the real conditions. Again we hoped we could learn from history. I started out with a question: does anybody know why Lake Worth is where it is or why? Ask your parents. Only one parent in all my years knew why Lake Worth was where it was. Wish I had a copy of this article.

I have a post on the history of local lakes, starting with Lake Worth. Most browsers allow you to save a webpage as a pdf file complete with text and images. Here is a link for how to save in Google Chrome.