In the middle of the nineteenth century as a civilian settlement grew up around the Army’s Fort Worth those early settlers were building a city from scratch. They needed everything.

Including education for their children.

John Peter Smith is said to have opened the first school in Fort Worth in 1853, occupying one of the military fort’s abandoned buildings.

John Peter Smith is said to have opened the first school in Fort Worth in 1853, occupying one of the military fort’s abandoned buildings.

For years schools were, like Smith’s, private. For example, in 1866 Captain John Hanna operated Fort Worth High School in the Masonic lodge hall.

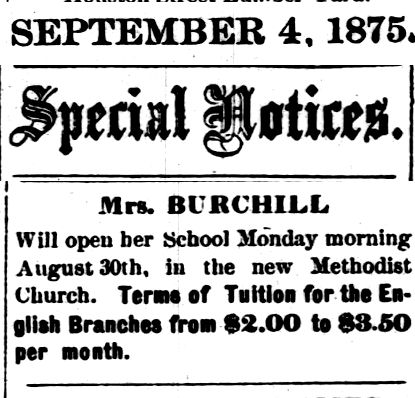

In 1875 Mrs. Belle Murray Burchill opened a private school in the new Fourth Street Methodist Church at East 4th and Jones streets.

In 1875 Mrs. Belle Murray Burchill opened a private school in the new Fourth Street Methodist Church at East 4th and Jones streets.

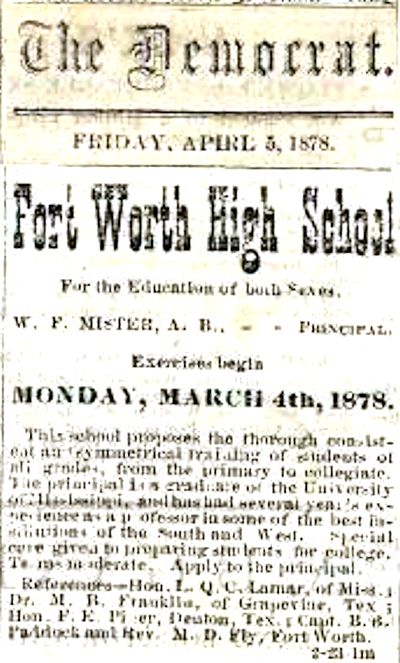

Some private schools taught only one gender.

But W. F. Mister’s private Fort Worth High School educated students “of both sexes.” His school was probably known locally as “the party school.”

In 1873 Fort Worth incorporated, although Fort Worth did not yet have the specific authority to tax residents to support a public school system.

So, soon after incorporation, Smith, Dr. Carroll Peak, Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt, and other civic leaders began a campaign to establish a free (taxpayer-supported) public school system for Fort Worth.

Today many of us attended public schools. As did our parents. And our children. We take public school for granted. But 150 years ago the notion of public schools was controversial. Some parents believed that children should be educated at home. In Fort Worth some residents, such as capitalist W. H. Davis, did not want to pay taxes to educate other people’s children. People who sent their children to private schools paid tuition, yes, but they paid the tuition of only their own children.

Meanwhile, on February 6, 1877 the city council created three wards, which divvied up the city geographically.

Thereafter voters in each ward elected an alderman to represent them on the city council.

The wards also would divvy up the city for the purposes of a school system.

In January 1877 the city council considered submitting to voters a proposal to establish a system of tax-supported free schools in Fort Worth.

Accordingly, an election was held on February 28, 1877. Note that there was one polling place: the mayor’s office.

The tax-supported school system was approved overwhelmingly: eighty-five votes to five. But opponents of the tax claimed the election was invalid because two-thirds of eligible voters in the city had not taken part in the election.

The opponents had a point. Fort Worth in 1877 had a population of about six thousand. Of that number, white women and children, African Americans, and white male non-property owners could not vote. But surely despite those exclusions there were enough eligible voters to make a ninety-voter turnout pretty unrepresentative.

Opponents took their case to the governor.

Sure enough, Texas Attorney General Hannibal Honestus Boone (go ahead: say his name out loud a few times. You know you want to) ruled the election invalid because fewer than two-thirds of qualified voters had voted.

Advocates of free schools persevered. In August 1878 a city ordinance providing for public schools was adopted. A school board was formed. The next year the board voted to pay Mayor R. E. Beckham $50 ($1,400 today) a year to act also as school superintendent.

On September 1, 1879 the city rented six spaces to serve as temporary classrooms in the three wards.

But opponents of the school tax had not given up. They again appealed to Attorney General Boone. He ruled, on a technicality, that Fort Worth’s public funds could not be diverted to schools.

The ward schools were closed.

But the advocates of tax-supported schools also didn’t give up. In April 1880 the Dallas Daily Herald reported that Fort Worth voters had overwhelmingly (425-45) passed a school tax of one-half percent.

The city council appointed James Jones Jarvis, John Hanna, and W. H. Baldridge to the school board.

By March 1881 the ward schools were again open. Mrs. Clara Peak Walden was the daughter of Dr. and Florence Peak, the sister of Howard Peak, and the first child born (1854) in Fort Worth. Note that the teachers met at the new Texas Wesleyan College, which at the time was housed downtown before moving to the campus on Cannon Street.

But Robert Lee Paschal later wrote of the standoff: “The trustees did not open the schools in the fall of 1881 because someone claimed that Fort Worth did not have a population of ten thousand, as required by law [to operate a school system], and went to law about it.”

The courts ruled that the burden was on the city of Fort Worth to prove that it had a population of at least ten thousand.

Councilmen objected that they had no funds to conduct a census. So, Smith and Van Zandt donated $300 ($8,000 today) to finance a private census. B. B. Paddock supervised the count, which showed Fort Worth’s population to be 11,130.

That put opponents of a school tax in the dunce corner to stay.

With the population challenge met, in 1882 Mayor Smith, Van Zandt, Peak, and others again campaigned for an election to allow the city to levy a tax for public schools.

Smith asked educator Alexander Hogg of Marshall to come to town to help persuade voters.

R. L. Paschal wrote: “He [Hogg] came . . . to make a speech in favor of local taxation for public schools.”

Judge James C. Scott recalled: “Professor Hogg carried the meeting with his eloquence, showing the progress in the management of the schools on a more thorough, universal education of the people. His strong principle was that education made more useful citizens and lessened crime.”

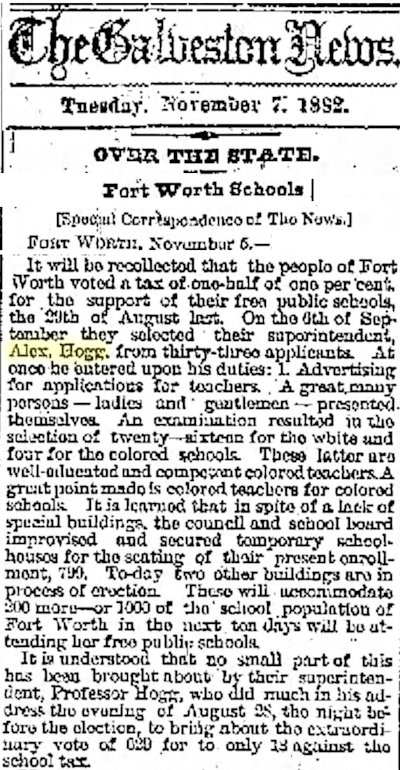

Later in 1882 Hogg’s speech was a factor when voters approved a tax of one-half percent to support a public school system. Hogg’s speech also was a factor in determining who would be the system’s first permanent superintendent: Alexander Hogg. He would serve a total of sixteen years over three terms.

Later in 1882 Hogg’s speech was a factor when voters approved a tax of one-half percent to support a public school system. Hogg’s speech also was a factor in determining who would be the system’s first permanent superintendent: Alexander Hogg. He would serve a total of sixteen years over three terms.

All obstacles now cleared, Hogg immediately began interviewing teachers—hiring sixteen white, four African American—for the new system’s 799 students. The city again rented space for classrooms but also began building two permanent schoolhouses.

Teachers were paid from $40 ($1,000 today) to $50 a month.

The city council appointed a new school board. Dr. Peak was president. Members were John Peter Smith, R. E. Beckham, and S. M. Fry.

It had taken four elections and at least three court cases over eight years, but Fort Worth finally had its tax-funded free public school system.