The arrival of ten railroads in Fort Worth during the decade of the 1880s (see Part 1) “wired” the city, connecting it to the rest of the world, albeit using boxcars, not data packets. The railroads also boosted the town’s economy and population. In 1880 Fort Worth’s population had been 6,663. By 1890 its population was 23,076.

For Fort Worth the railroads created jobs and put money into circulation: After all, people were needed to operate the trains, repair the trains and trestles, sell the tickets, maintain old track, lay new track. The railroads had a ripple effect: Those “boys around the depot” had families, and they all needed places to live, to eat, to worship, to go to school, to be entertained, to buy a washtub or a woolen cap or a wood stove. Those needs created non-railroad jobs. Jobs brought people. When the first railroad arrived in 1876, Fort Worth had a population of about six thousand. The publisher of the city directory estimated the population in 1883, after four more railroads had arrived, at fifteen thousand. Clip is from the February 25, 1883 Gazette.

For Fort Worth the railroads created jobs and put money into circulation: After all, people were needed to operate the trains, repair the trains and trestles, sell the tickets, maintain old track, lay new track. The railroads had a ripple effect: Those “boys around the depot” had families, and they all needed places to live, to eat, to worship, to go to school, to be entertained, to buy a washtub or a woolen cap or a wood stove. Those needs created non-railroad jobs. Jobs brought people. When the first railroad arrived in 1876, Fort Worth had a population of about six thousand. The publisher of the city directory estimated the population in 1883, after four more railroads had arrived, at fifteen thousand. Clip is from the February 25, 1883 Gazette.

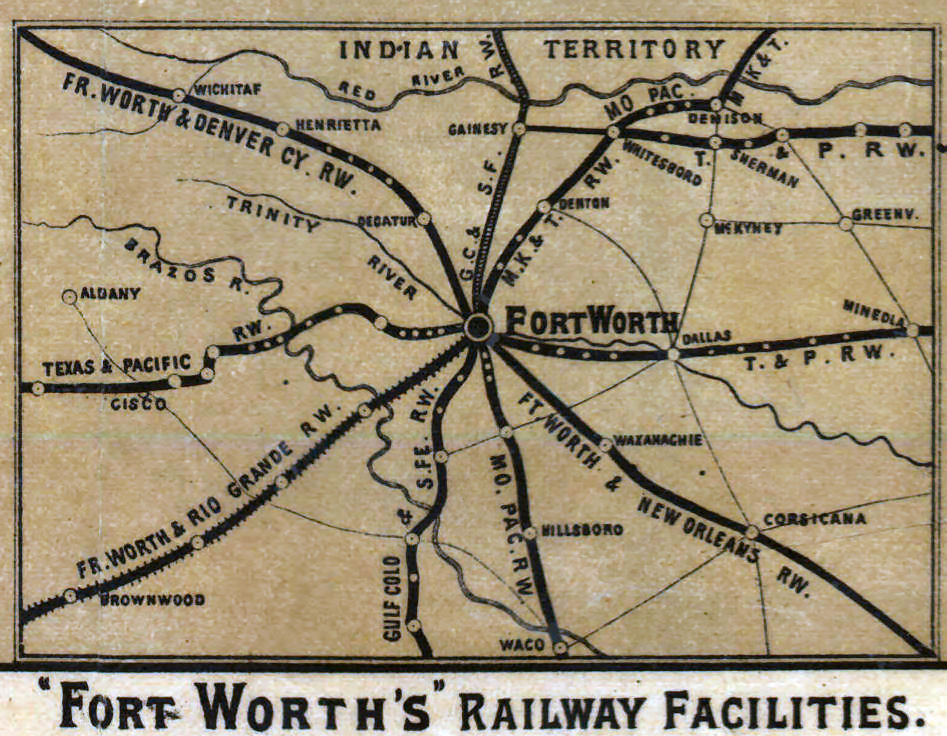

This inset from an 1886 Wellge bird’s-eye-view map shows B. B. Paddock’s tarantula map with an arachnid’s requisite eight legs plus one. The Fort Worth & Rio Grande Railway had been chartered in 1885 but was not in operation until 1887.

This inset from an 1886 Wellge bird’s-eye-view map shows B. B. Paddock’s tarantula map with an arachnid’s requisite eight legs plus one. The Fort Worth & Rio Grande Railway had been chartered in 1885 but was not in operation until 1887.

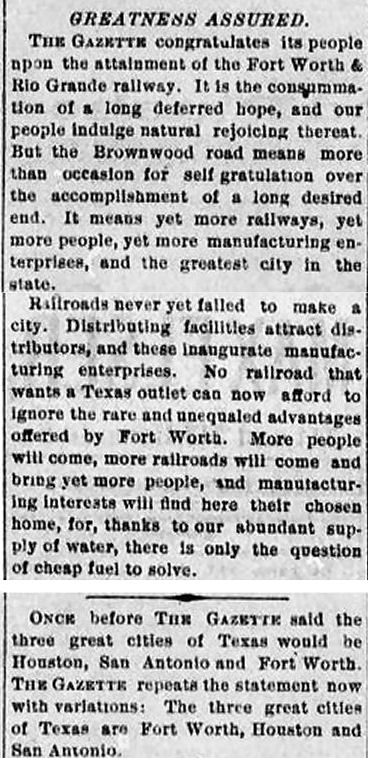

In fact, the October 29, 1886 edition of Paddock’s Fort Worth Gazette celebrated the fact that Fort Worth had just raised $40,000 ($1 million today) to subsidize the Fort Worth & Rio Grande. The Gazette said Fort Worth was now assured of greatness. Of course, Paddock’s newspaper may have been biased: Paddock was president of that railroad. (In the bottom clip listing the great cities of Texas, notice the conspicuous absence of the city just downstream.)

In fact, the October 29, 1886 edition of Paddock’s Fort Worth Gazette celebrated the fact that Fort Worth had just raised $40,000 ($1 million today) to subsidize the Fort Worth & Rio Grande. The Gazette said Fort Worth was now assured of greatness. Of course, Paddock’s newspaper may have been biased: Paddock was president of that railroad. (In the bottom clip listing the great cities of Texas, notice the conspicuous absence of the city just downstream.)

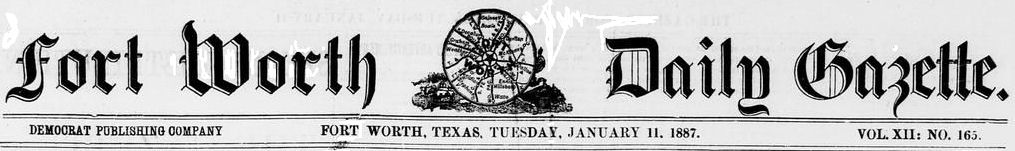

On January 11, 1887, a version of Paddock’s tarantula map, now with eleven legs, became the centerpiece of the nameplate of the Gazette.

On January 11, 1887, a version of Paddock’s tarantula map, now with eleven legs, became the centerpiece of the nameplate of the Gazette.

Also in 1887 the Gazette began published a daily column devoted to local railroad news.

Also in 1887 the Gazette began published a daily column devoted to local railroad news.

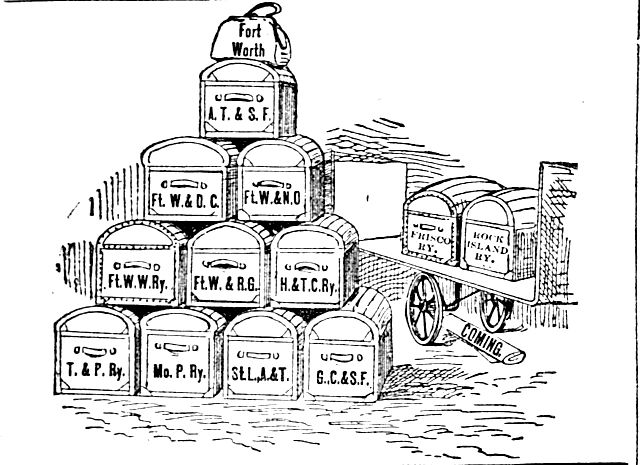

On April 1, 1888, when the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad extended service between the two namesake cities, the Gazette printed this illustration listing the city’s railroads: Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, Fort Worth & Denver City, Fort Worth & New Orleans, Fort Worth Western (to Throckmorton), Fort Worth & Rio Grande, Houston & Texas Central, Texas & Pacific, Missouri Pacific, St. Louis, Arkansas & Texas, and Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe. The Gazette sometimes implied that railroads existed or served Fort Worth when they were merely planned. An example is the Fort Worth Western. And the two railroads labeled “Coming” would not be coming for a few years.

On April 1, 1888, when the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad extended service between the two namesake cities, the Gazette printed this illustration listing the city’s railroads: Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, Fort Worth & Denver City, Fort Worth & New Orleans, Fort Worth Western (to Throckmorton), Fort Worth & Rio Grande, Houston & Texas Central, Texas & Pacific, Missouri Pacific, St. Louis, Arkansas & Texas, and Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe. The Gazette sometimes implied that railroads existed or served Fort Worth when they were merely planned. An example is the Fort Worth Western. And the two railroads labeled “Coming” would not be coming for a few years.

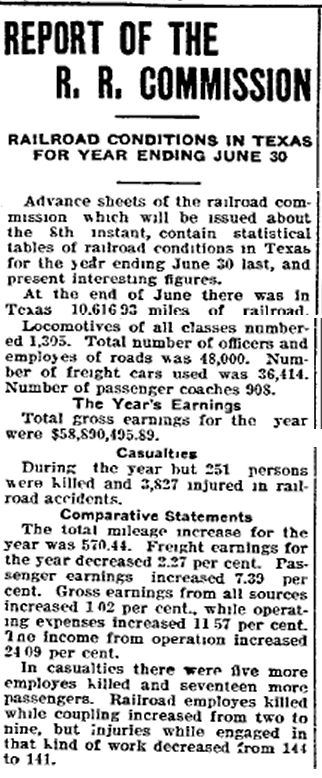

By 1902, with the coming of the Stockyards and packing plants, Fort Worth needed even more railroad service. That meant more track, more bridges, more trains, more jobs, more ripple effect. This Fort Worth Telegram report of November 3, 1902, shows that railroads in Texas could be both profitable and dangerous. (Gross earnings of $58 million would be $1.5 billion today.)

By 1902, with the coming of the Stockyards and packing plants, Fort Worth needed even more railroad service. That meant more track, more bridges, more trains, more jobs, more ripple effect. This Fort Worth Telegram report of November 3, 1902, shows that railroads in Texas could be both profitable and dangerous. (Gross earnings of $58 million would be $1.5 billion today.)

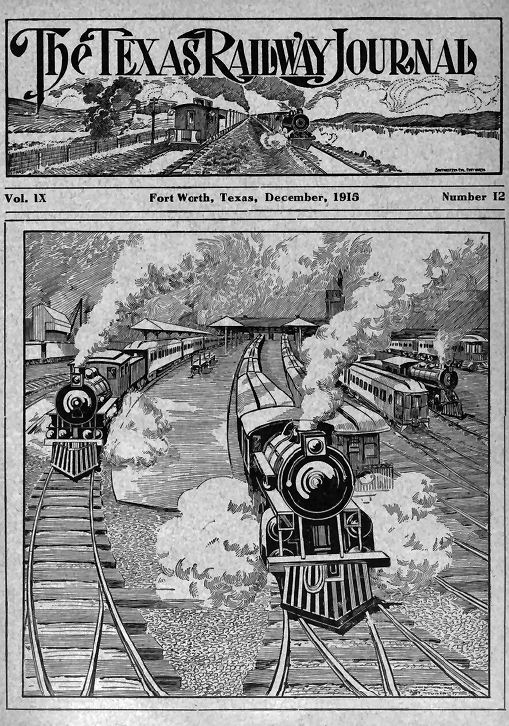

By 1907 Cowtown was a bona fide rail center. In that year Texas Railway Journal, a union publication that eventually would cover the southwestern United States, moved from Austin to Fort Worth because, publisher C. F. Goodridge said, “[T]he toot of the engine whistle and the ‘bumping’ of the cars are much more frequent.”

By 1907 Cowtown was a bona fide rail center. In that year Texas Railway Journal, a union publication that eventually would cover the southwestern United States, moved from Austin to Fort Worth because, publisher C. F. Goodridge said, “[T]he toot of the engine whistle and the ‘bumping’ of the cars are much more frequent.”

By 1913 The Book of Fort Worth said the city handled 210 freight trains and 203 passenger trains daily.

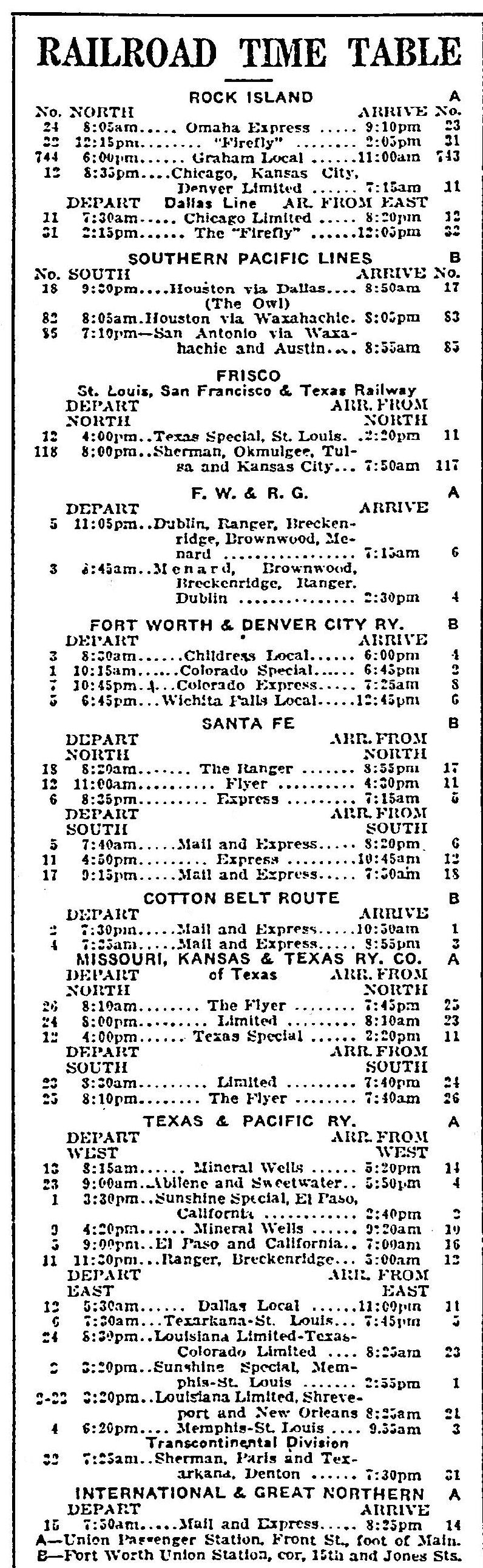

By 1921 Paddock’s tarantula had even more legs, including the Rock Island and International & Great Northern. In this time table from 1921 notice the named trains: Firefly, Flyer, Owl, Sunshine Special. This time table does not include freight trains. Or the interurban and city streetcars! All those passenger trains were served by just two stations. What the town must have looked like with all those rails and roundhouses and turntables and repair sheds, with all those monstrous steaming, smoking locomotives pulling cars through town night and day. What the town must have smelled like with all that coal and oil and smoke. What the town must have sounded like with all those bells and whistles and stream vents, all that chugging of locomotives, clanging of couplers, squealing of brakes, and clattering of iron wheels on iron rails.

By 1921 Paddock’s tarantula had even more legs, including the Rock Island and International & Great Northern. In this time table from 1921 notice the named trains: Firefly, Flyer, Owl, Sunshine Special. This time table does not include freight trains. Or the interurban and city streetcars! All those passenger trains were served by just two stations. What the town must have looked like with all those rails and roundhouses and turntables and repair sheds, with all those monstrous steaming, smoking locomotives pulling cars through town night and day. What the town must have smelled like with all that coal and oil and smoke. What the town must have sounded like with all those bells and whistles and stream vents, all that chugging of locomotives, clanging of couplers, squealing of brakes, and clattering of iron wheels on iron rails.

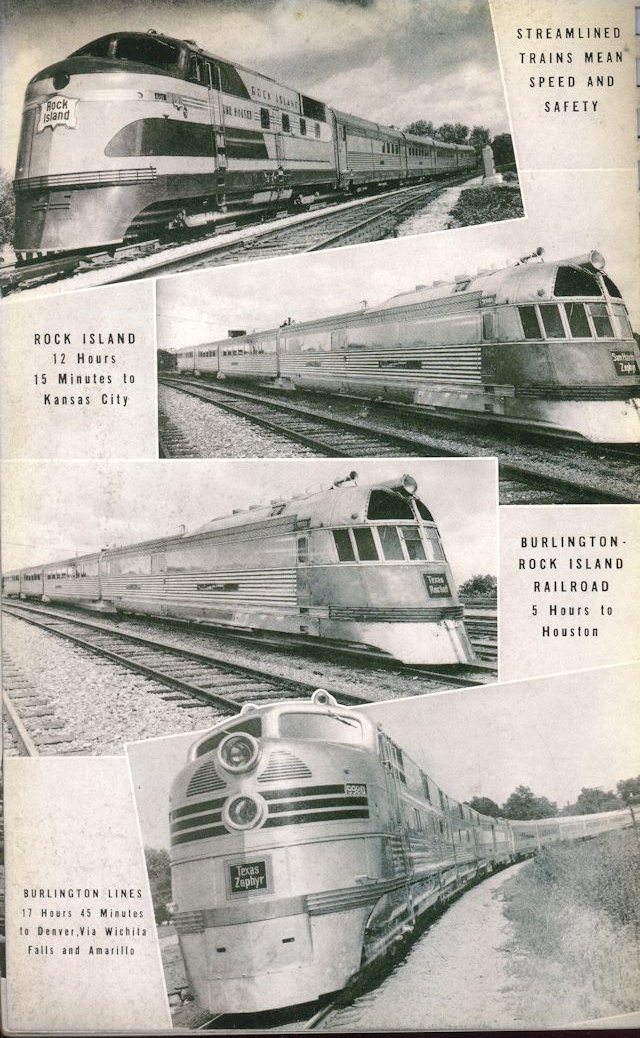

The age of steam ended in mid-twentieth century, of course, as streamlined diesel engines shouldered steam locomotives onto a siding. Today’s diesel locomotives are quieter, cleaner, more efficient: twelve hours to Kansas City, five hours to Houston, eighteen hours to Denver. (W. D. Smith photo from Fort Worth in Pictures, 1940.)

The age of steam ended in mid-twentieth century, of course, as streamlined diesel engines shouldered steam locomotives onto a siding. Today’s diesel locomotives are quieter, cleaner, more efficient: twelve hours to Kansas City, five hours to Houston, eighteen hours to Denver. (W. D. Smith photo from Fort Worth in Pictures, 1940.)

And although Fort Worth’s Tower 55 remains a major rail crossroads, far more freight than passengers crosses it.

In the age of steam, locomotives ran on coal. Today they run on diesel but haul coal.

In the age of steam, locomotives ran on coal. Today they run on diesel but haul coal.

And today vehicular traffic and rail traffic are largely segregated by underpasses and overpasses.

For the most part.

For the most part.

Today, just as that other major factor in Fort Worth history, the river, flows through us largely unnoticed, trains move among us largely unnoticed. But the next time you hear the air horn of a TRE commuter train or see downtown’s art deco cathedral of transportation built by Texas & Pacific—the line that began it all in 1876—try to imagine the sights and smells and sounds of Fort Worth’s billowing, bellowing age of steam.