You may recall that in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Huck’s friend Jim “had a hair-ball as big as your fist, which had been took out of the fourth stomach of an ox, and he used to do magic with it. He said there was a spirit inside of it, and it knowed everything.” And the Harry Potter books feature bezoars, which are stonelike masses taken from the stomach of a goat.

A hairball and a bezoar are also called a “madstone.” A madstone is a calcified hairball produced in the stomach of an animal, usually a cud-chewer such as a cow or deer or goat.

Huck Finn and Harry Potter are fiction. But many people of the nineteenth century believed in the medical value of madstones, especially to treat not only rabies (hence the “mad” in madstone) but also insect stings and snakebites. Madstones were highly prized, handed down from generation to generation like heirlooms. In a medical emergency people traveled miles to find a madstone. The best madstones were said to be from an albino or “witch” deer.

Medicine (even folk medicine), like any other science, is exacting. According to one source, medical purists observed rules for the use of a madstone:

• If a madstone is bought or sold it will lose its curative power.

• The owner of a madstone must not charge for its use.

• The shape of a madstone must not be changed.

• The patient must go to the owner of the madstone, not the other way around (no house calls).

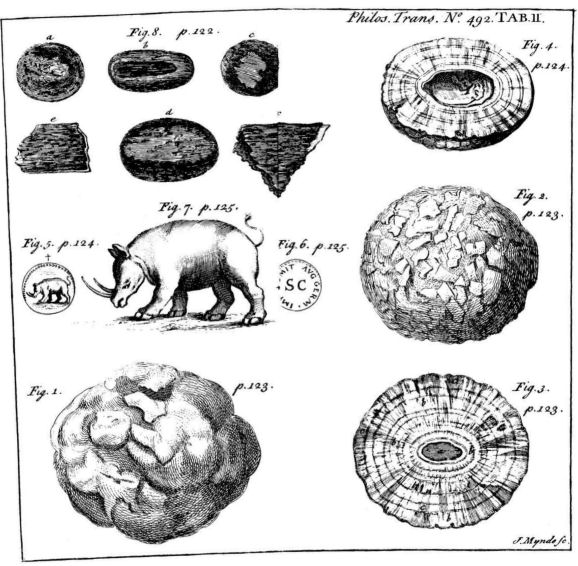

Huck Finn is set in 1845. But people used madstones long before—and after—that date. This illustration is from a 1749 pamphlet written by Irish physician Hans Sloane about a rhinoceros madstone.

Huck Finn is set in 1845. But people used madstones long before—and after—that date. This illustration is from a 1749 pamphlet written by Irish physician Hans Sloane about a rhinoceros madstone.

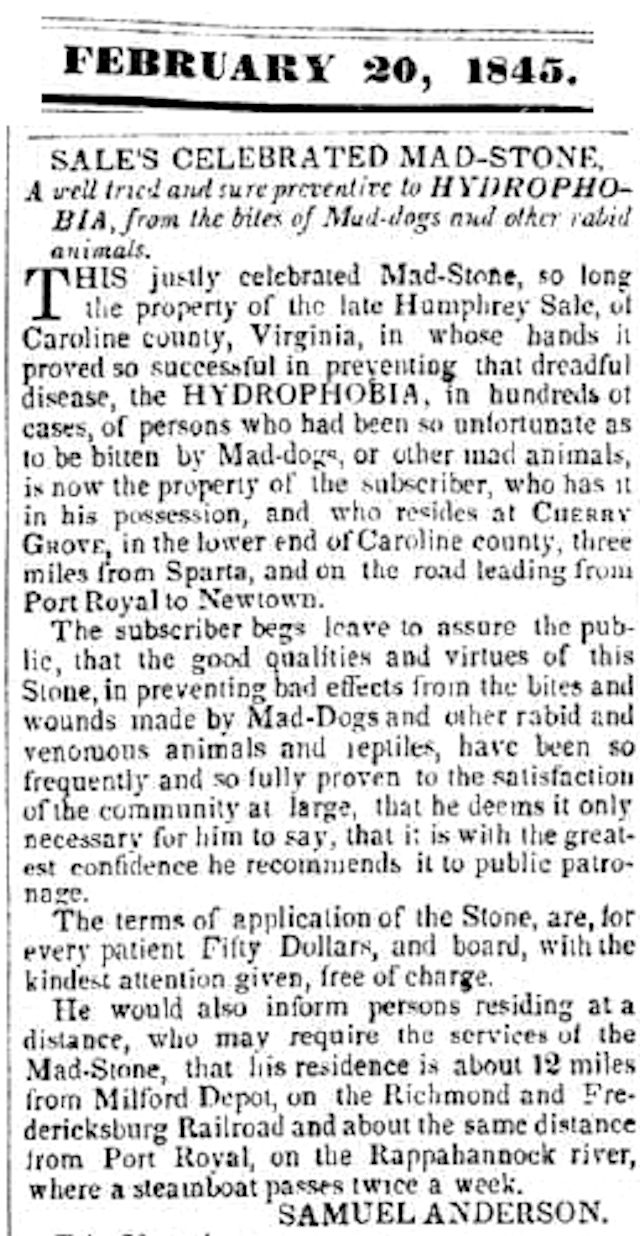

This classified ad appeared many times in the Examiner of Richmond, Virginia in 1845. Samuel Anderson had come into possession of “Sale’s celebrated mad-stone, a well tried and sure preventive to hydrophobia.” Anderson charged $50 ($1,300 today), but that fee included board (“with the kindest attention given”). Anderson pointed out that he and his madstone were accessible by railroad and steamboat.

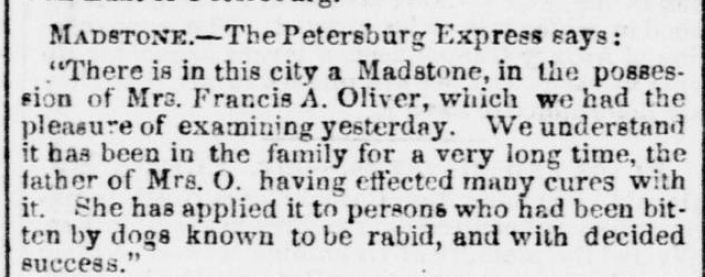

Nine years later in Richmond, the Daily Dispatch in 1854 reported on another madstone that had “effected many cures.”

Nine years later in Richmond, the Daily Dispatch in 1854 reported on another madstone that had “effected many cures.”

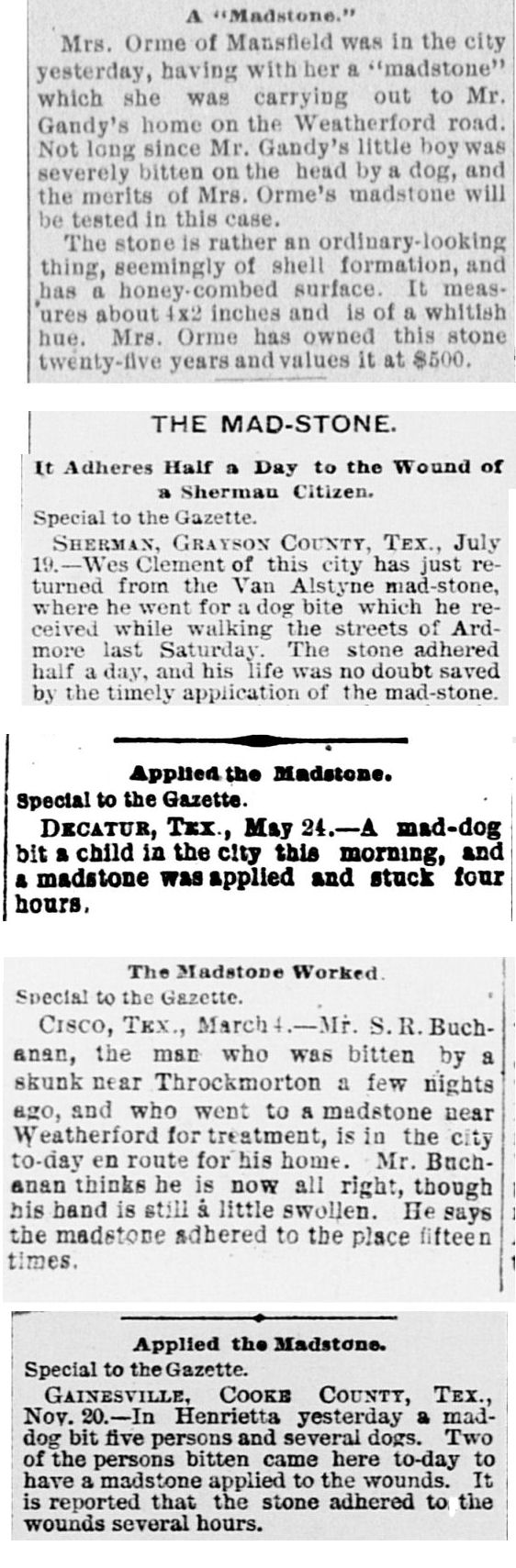

Texas newspapers of the nineteenth century also contained hundreds of reports of madstones being applied to patients, usually after those persons had been bitten by a dog, cat, skunk, or cow that was believed to be rabid. The procedure varied among practitioners, but many boiled their madstone in milk before applying the stone to the wound. If the madstone “adhered” to the wound, that indicated that “poison” was present in the victim. When the madstone fell off, it was again boiled in milk and applied to the wound. When the madstone turned the milk green, all the poison had been removed. The longer the madstone adhered to the wound, the more poison it removed and the better the victim’s chance of recovery.

Even though a rabies vaccine was developed in 1885, Fort Worth newspapers of the 1880s and 1890s contain dozens of reports about the use of madstones to treat rabies.

Even though a rabies vaccine was developed in 1885, Fort Worth newspapers of the 1880s and 1890s contain dozens of reports about the use of madstones to treat rabies.

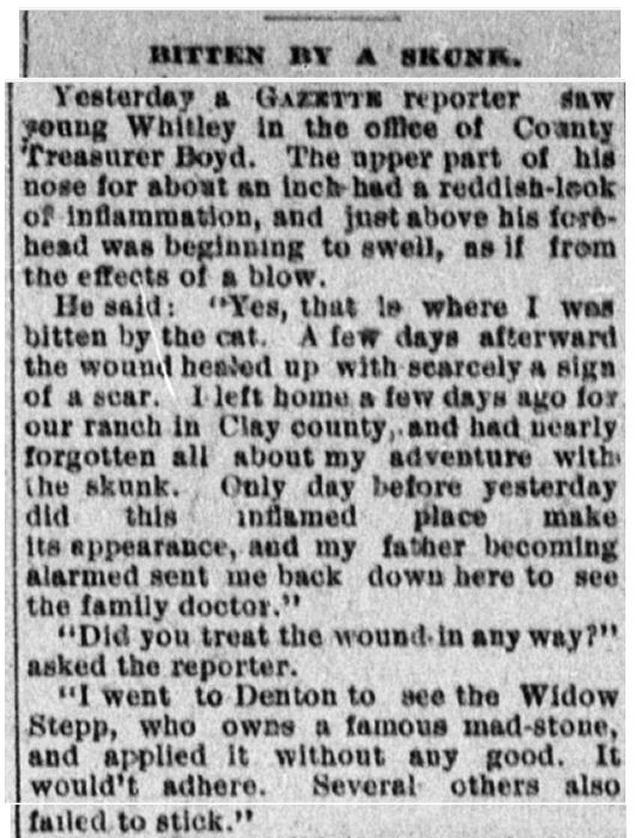

A Fort Worth Gazette reporter interviewed a man bitten by a polecat who said that the widow Stepp in Denton had a “famous madstone.”

A Fort Worth Gazette reporter interviewed a man bitten by a polecat who said that the widow Stepp in Denton had a “famous madstone.”

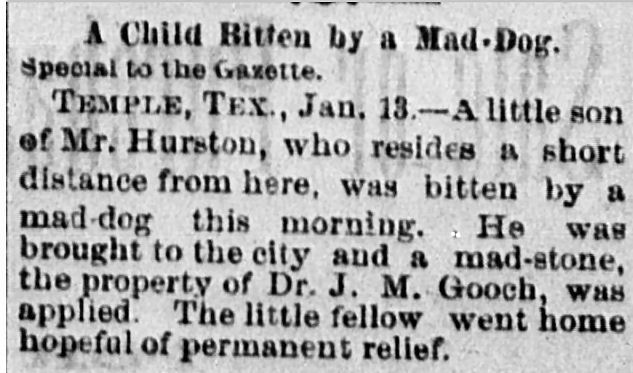

A Dr. Gooch of Temple, apparently a physician, owned a madstone.

A Dr. Gooch of Temple, apparently a physician, owned a madstone.

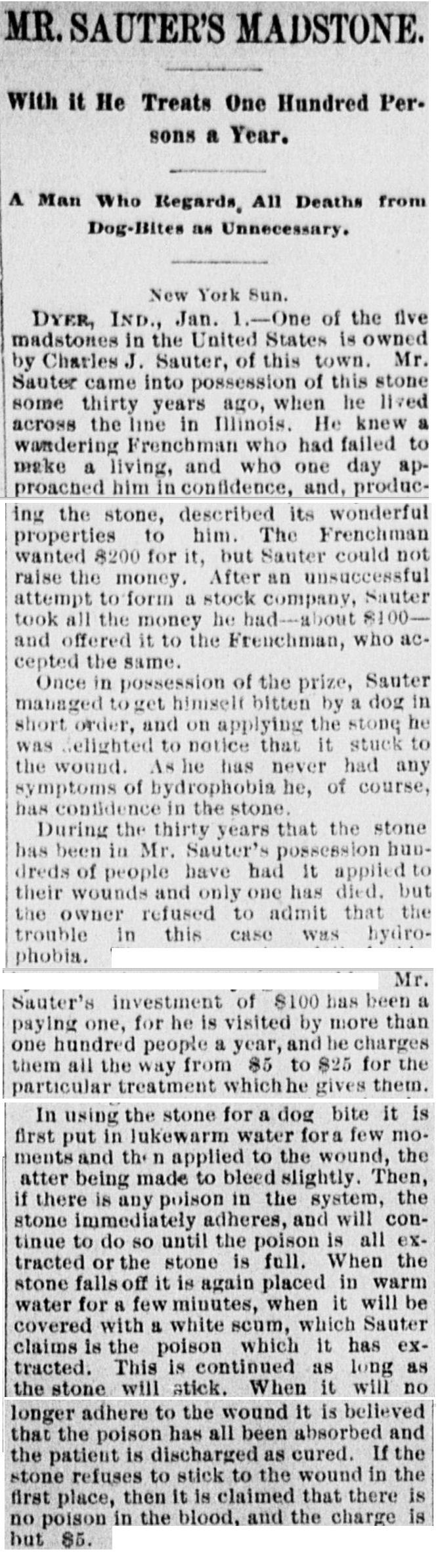

This article explains how a madstone is applied and how it heals. Mr. Sauter of Indiana claimed that his madstone was one of only five in the United States.

This article explains how a madstone is applied and how it heals. Mr. Sauter of Indiana claimed that his madstone was one of only five in the United States.

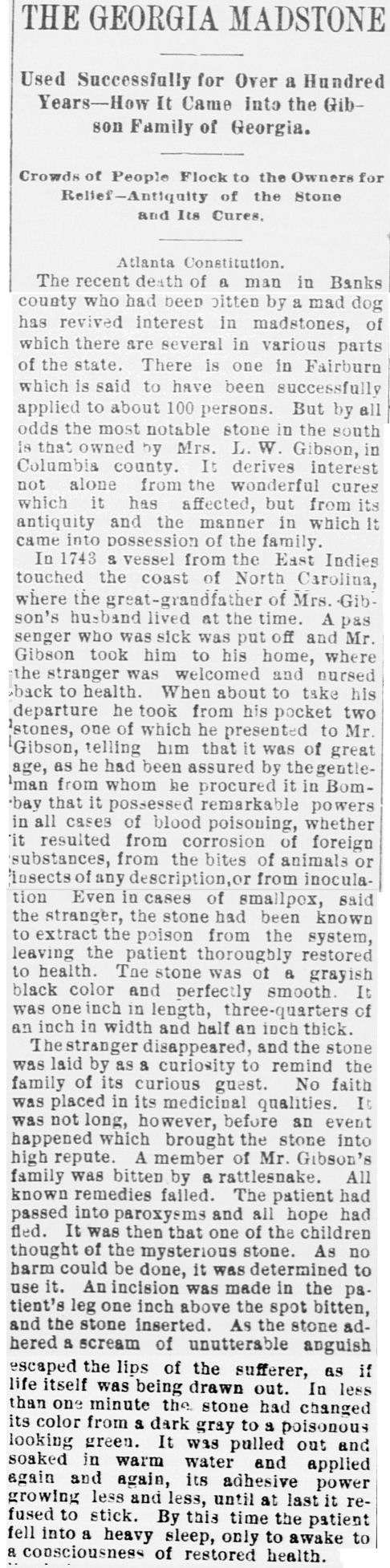

And yet such wondrous concretions seemed to have been in all parts of the country. And to have been treated like family jewels. The Gibson madstone in Georgia had been in the family a century and had cured about one hundred people.

And yet such wondrous concretions seemed to have been in all parts of the country. And to have been treated like family jewels. The Gibson madstone in Georgia had been in the family a century and had cured about one hundred people.

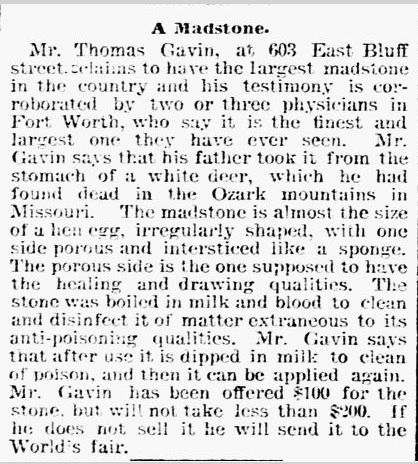

And a Fort Worth man claimed to have the largest madstone in the country and was considering exhibiting it at the World’s Fair of 1893. Note that two or three Fort Worth physicians attested to the fineness of Mr. Gavin’s madstone. Clip is from the June 23, 1891 Fort Worth Gazette.

And a Fort Worth man claimed to have the largest madstone in the country and was considering exhibiting it at the World’s Fair of 1893. Note that two or three Fort Worth physicians attested to the fineness of Mr. Gavin’s madstone. Clip is from the June 23, 1891 Fort Worth Gazette.

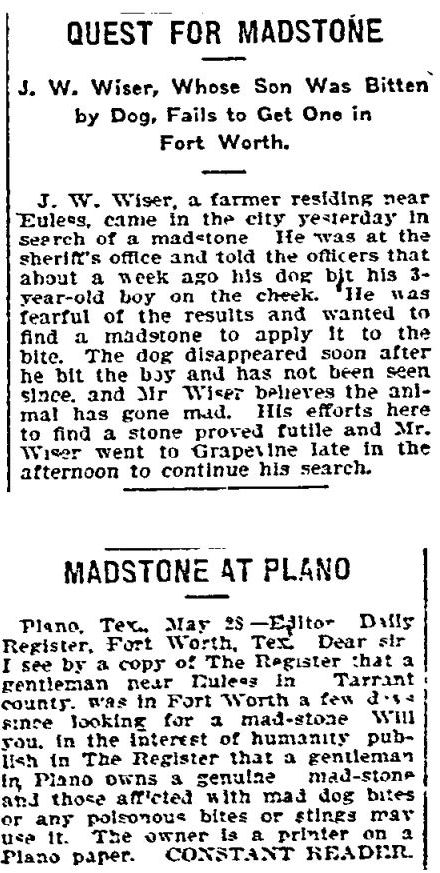

These two clips are from the Fort Worth Register in 1902. A Euless man was seeking a madstone. Two days later the paper printed a letter from a reader advising where such a wondrous stone might be found.

These two clips are from the Fort Worth Register in 1902. A Euless man was seeking a madstone. Two days later the paper printed a letter from a reader advising where such a wondrous stone might be found.

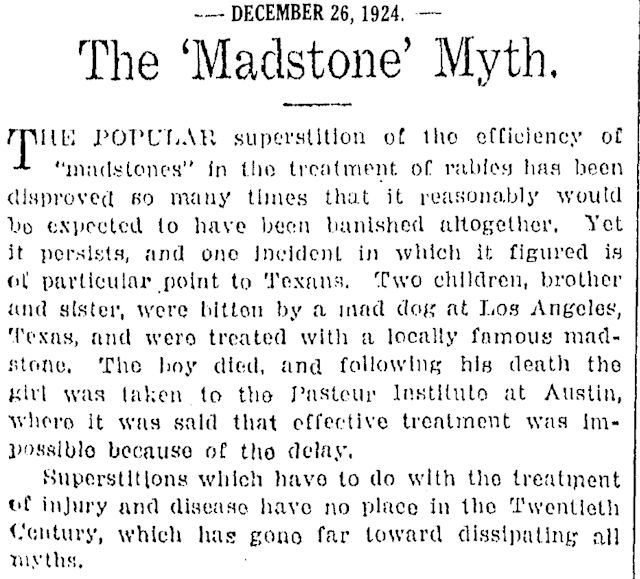

Reliance on madstones lingered into the twentieth century. In 1924 a Star-Telegram editorial lamented the myth of the madstone after a madstone had been used with tragic results in Los Angeles, Texas (who knew? Los Angeles, Texas is between San Antonio and Laredo).

Reliance on madstones lingered into the twentieth century. In 1924 a Star-Telegram editorial lamented the myth of the madstone after a madstone had been used with tragic results in Los Angeles, Texas (who knew? Los Angeles, Texas is between San Antonio and Laredo).

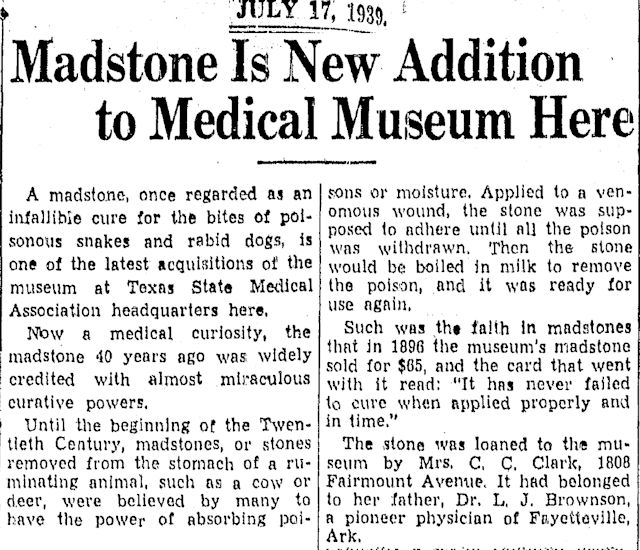

In 1939 the state medical association’s museum on El Paso Street added a madstone to its collection, on loan from a resident of Fairmount.

In 1939 the state medical association’s museum on El Paso Street added a madstone to its collection, on loan from a resident of Fairmount.

By midcentury the application of a madstone boiled in milk to cure disease in a patient was regarded as quaint quackery of the past and was virtually forsaken as a medical procedure. Just as well. Imagine trying to get Blue Cross to pay for that.

THIS WAS A VERY INTRESTING ARTICLE DO YOU KNOW OF ANYONE THAT HAS A MADSTONE THAT CAN BE AQUIRED OR TALK TO FOR MORE INFORMATION. THANK YOU IN ADVANCE FOR YOUR ASSISTANCE.

MY PHONE NUMBER IS 704-418-5457

If you Google “bezoar stone for sale” you will find at least one website claiming to sell madstones.

Very interesting article. I had never heard of a madstone before. Thanks, for teaching this old dog a new trick!

Thanks, Scott. That odd bit of folk medicine had a surprisingly long shelf life.