Just after noon on April 3, 1886 near the intersection of two sets of railroad tracks in the open countryside south of Fort Worth, two groups of men stood. They were facing north toward town. Watching. Perhaps for a plume of black smoke. Listening. Perhaps for a chug or a whistle. Yes, they were waiting for a train. One group of men was armed. The other group was unarmed. But both groups were defiant.

Soon the train those men were waiting for would appear from the north, and locomotive smoke would mingle with gun smoke as Cowtown got its first taste of big-city labor violence. When the smoke cleared, three peace officers would be shot. One lawman/gunfighter’s reputation would be tarnished. And newspapers around the country the next day would be writing about what had just transpired at a place in Texas with the bucolic name “Buttermilk Junction.”

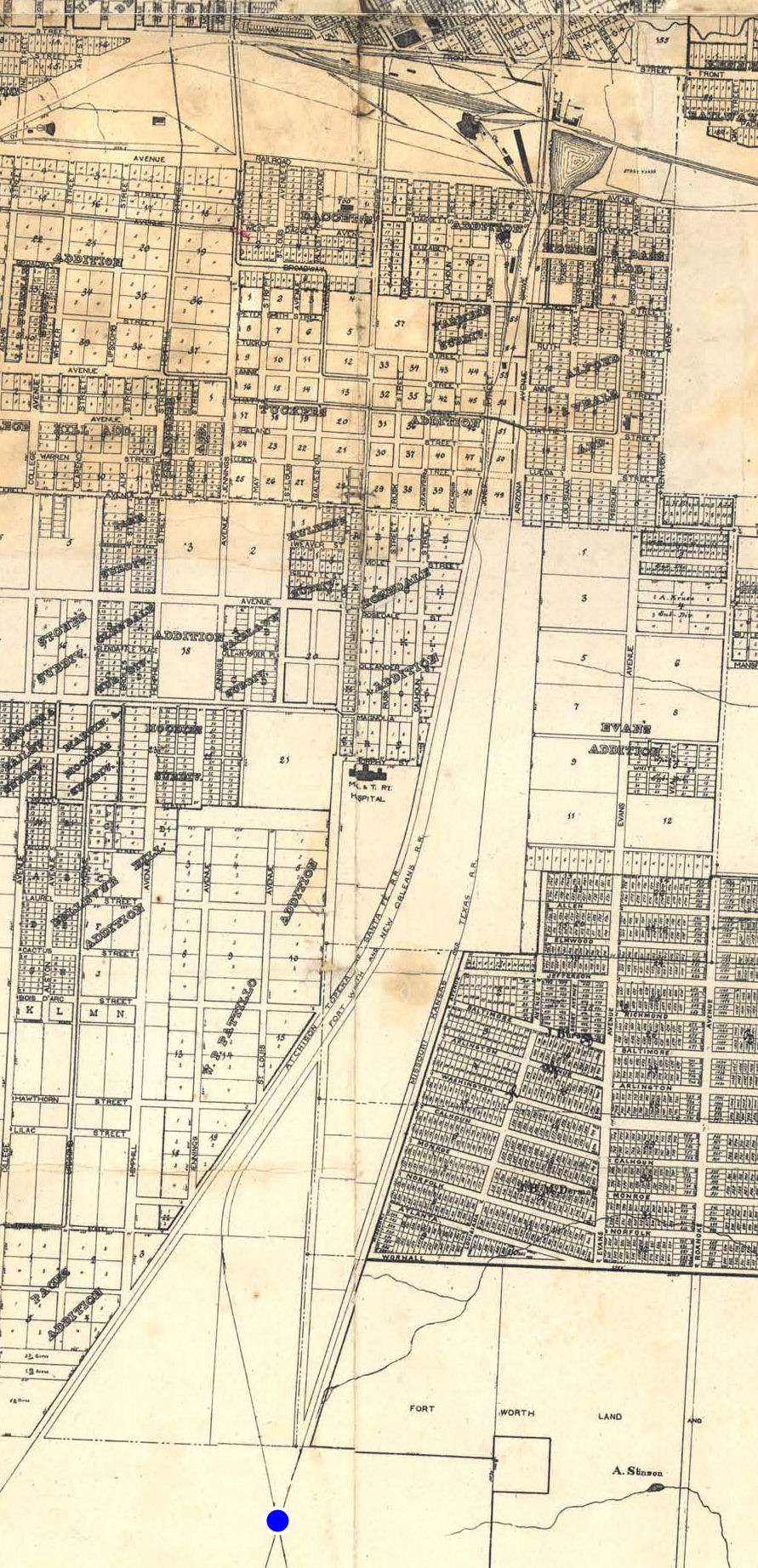

The blue dot at the bottom of the map, showing Fort Worth in 1890, marks where the two groups of men were waiting: where the tracks of the Fort Worth & New Orleans railroad and the tracks of the Missouri Pacific railroad intersected. Today’s Lancaster Avenue would be at the top of the map. The railroad intersection was 1.3 miles south of the Missouri Pacific Infirmary (later “St. Joseph Hospital”). As you can see, that intersection was out in the country back then. (Map from Pete Charlton’s “The Lost Antique Maps of Texas: Fort Worth & Tarrant County, Volume 2” CD.)

The blue dot at the bottom of the map, showing Fort Worth in 1890, marks where the two groups of men were waiting: where the tracks of the Fort Worth & New Orleans railroad and the tracks of the Missouri Pacific railroad intersected. Today’s Lancaster Avenue would be at the top of the map. The railroad intersection was 1.3 miles south of the Missouri Pacific Infirmary (later “St. Joseph Hospital”). As you can see, that intersection was out in the country back then. (Map from Pete Charlton’s “The Lost Antique Maps of Texas: Fort Worth & Tarrant County, Volume 2” CD.)

This photo shows where Buttermilk Junction would be today, near Cantey and St. Louis streets on the near South Side: the tracks of the Fort Worth & New Orleans railroad on the left, the tracks of the Missouri Pacific railroad on the right. (The two tracks were rerouted in the 1990s; now the two tracks approach each other but do not intersect.)

This photo shows where Buttermilk Junction would be today, near Cantey and St. Louis streets on the near South Side: the tracks of the Fort Worth & New Orleans railroad on the left, the tracks of the Missouri Pacific railroad on the right. (The two tracks were rerouted in the 1990s; now the two tracks approach each other but do not intersect.)

Today all is quiet along those tracks. But on April 4, 1886 the New York Times lamented “the murderous acts of the Fort Worth ruffians.”

Likewise the Louisville Courier-Journal wrote: “The labor organizations must demonstrate their power to enforce their decrees, and they must separate themselves from the marauders, who seem to be in the ascendancy in Fort Worth.”

And the Florida Times Union wrote: “The bloody deed at Fort Worth will be condemned, we are sure, by the laboring men of the country just as emphatically as by any other class of citizens.”

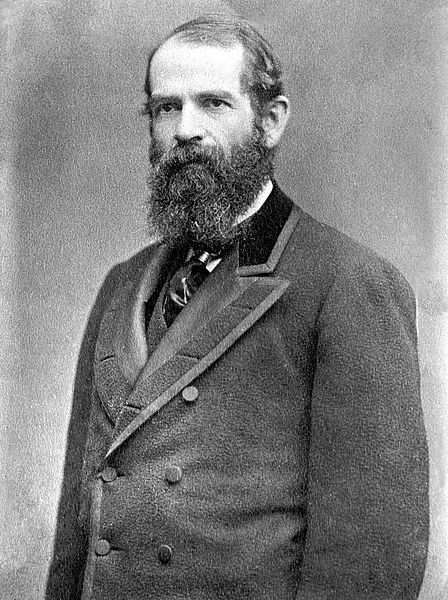

Some Buttermilk background: In 1886 railroad magnate Jay Gould (photo from Wikipedia) wanted to weaken the power of the Knights of Labor, the country’s largest labor organization. The Knights of Labor wanted to weaken the power of Gould.

Some Buttermilk background: In 1886 railroad magnate Jay Gould (photo from Wikipedia) wanted to weaken the power of the Knights of Labor, the country’s largest labor organization. The Knights of Labor wanted to weaken the power of Gould.

Fair enough.

In February a Texas & Pacific railroad foreman in Marshall, Texas was fired for attending a union meeting on company time. His union responded by striking, demanding better working conditions and regular paydays. The strike spread to other railroads, other unions, other states. Thousands of workers struck in Texas, Missouri, Arkansas, Kansas, and Illinois. Trains stopped running in Texarkana, Little Rock, Kansas City, St. Louis. Railroads were a vital mode of intercity transportation and communication in those days before airplanes and the Internet. The effect of the strike was staggering.

Nationally, Gould, who once said, “I can hire one-half of the working class to kill the other half,” brought in nonunion workers and Pinkerton detectives to break the strike—and some heads. Violence broke out as strikers and sympathizers uncoupled cars, seized railroad switches, vandalized railroad equipment, and stood on tracks to block trains. Sometimes even women and children stood on tracks.

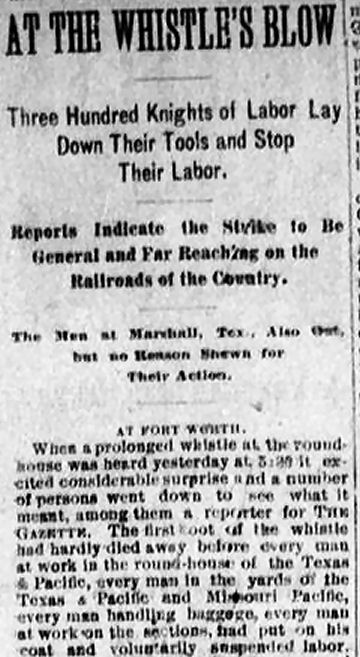

Locally, on March 2 the Fort Worth Gazette reported that three hundred T&P and Missouri Pacific workers had gone on strike, their goal being to stop rail traffic into and out of Fort Worth. Soon it was common to see armed men—on both sides of the strike—loitering near rail yards and tracks, as if waiting for—hoping for?—something to happen.

Locally, on March 2 the Fort Worth Gazette reported that three hundred T&P and Missouri Pacific workers had gone on strike, their goal being to stop rail traffic into and out of Fort Worth. Soon it was common to see armed men—on both sides of the strike—loitering near rail yards and tracks, as if waiting for—hoping for?—something to happen.

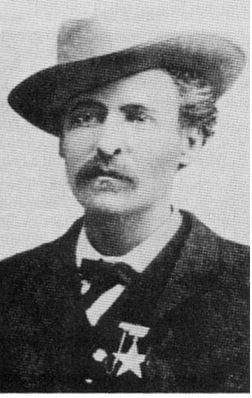

As the threat of violence grew in Fort Worth, Sheriff Walter Maddox hired extra deputies. Among them was former city marshal Jim Courtright. (Photo from Tarrant County College NE.) After Courtright’s arrest on October 18, 1884 and his escape the next day, Courtright had avoided Fort Worth for fifteen months. But in January 1886 he had returned and reopened his T.I.C. detective agency.

As the threat of violence grew in Fort Worth, Sheriff Walter Maddox hired extra deputies. Among them was former city marshal Jim Courtright. (Photo from Tarrant County College NE.) After Courtright’s arrest on October 18, 1884 and his escape the next day, Courtright had avoided Fort Worth for fifteen months. But in January 1886 he had returned and reopened his T.I.C. detective agency.

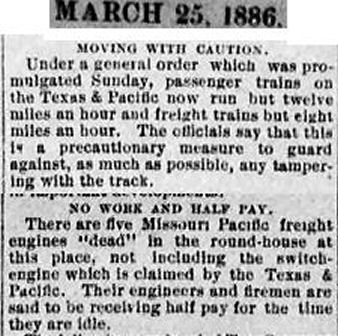

On March 25 the Gazette reported that the few trains that were running were moving slowly in case the tracks had been vandalized.

On March 25 the Gazette reported that the few trains that were running were moving slowly in case the tracks had been vandalized.

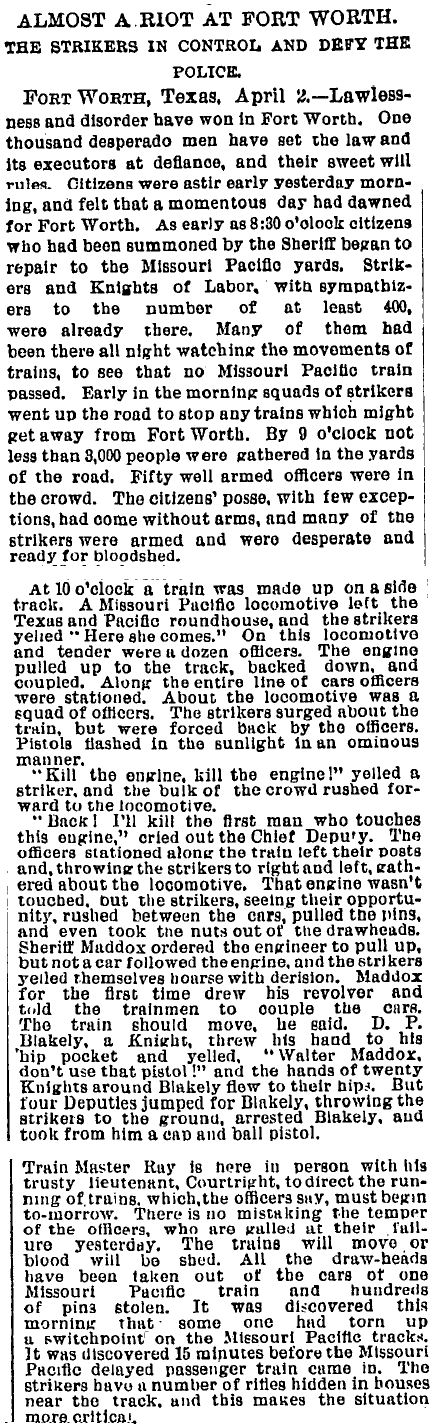

On April 3 the New York Times reported a confrontation between chief sheriff’s deputy Jim Maddox (the sheriff’s brother) and strikers who were attempting to block a train. “I’ll kill the first man who touches this engine,” Jim Maddox warned strikers. The report also mentions Courtright and acts of theft and sabotage. (To “kill” an engine meant to extinguish the fire under the boiler and to empty the boiler of water and steam, thus disabling the engine.)

On April 3 the New York Times reported a confrontation between chief sheriff’s deputy Jim Maddox (the sheriff’s brother) and strikers who were attempting to block a train. “I’ll kill the first man who touches this engine,” Jim Maddox warned strikers. The report also mentions Courtright and acts of theft and sabotage. (To “kill” an engine meant to extinguish the fire under the boiler and to empty the boiler of water and steam, thus disabling the engine.)

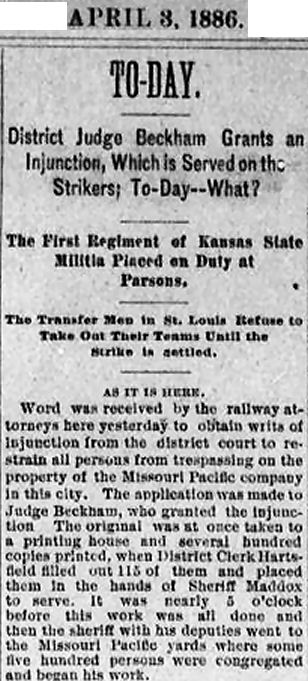

The strike dominated headlines across the country for most of March and April. As the strike continued, the railroads pressured cities to get tough with strikers. The railroads also went to court to get injunctions issued against strikers. Such injunctions put the railroads in a win-win position: If the strikers obeyed an injunction, trains, manned by nonunion replacements, would run. If the strikers disobeyed an injunction, they were breaking the law and could be acted against.

The strike dominated headlines across the country for most of March and April. As the strike continued, the railroads pressured cities to get tough with strikers. The railroads also went to court to get injunctions issued against strikers. Such injunctions put the railroads in a win-win position: If the strikers obeyed an injunction, trains, manned by nonunion replacements, would run. If the strikers disobeyed an injunction, they were breaking the law and could be acted against.

On April 2 an injunction was issued in Fort Worth: Strikers were forbidden to be on Missouri Pacific property and to interfere with railroad traffic. Clip is from the Gazette of April 3.

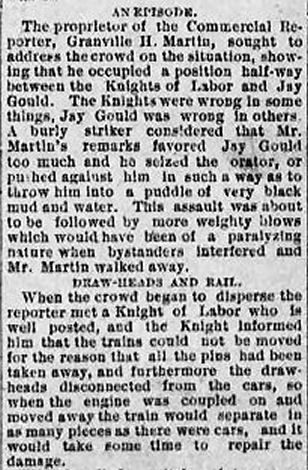

As the injunction went into effect, tensions escalated in Fort Worth. The Gazette on April 3 reported an altercation and an act of vandalism.

As the injunction went into effect, tensions escalated in Fort Worth. The Gazette on April 3 reported an altercation and an act of vandalism.

The injunction was less than a day old when Missouri Pacific officials decided to test the strikers. A Missouri Pacific train, with five railroad guards and eight of Sheriff Maddox’s special deputies on board, would attempt to break the strikers’ blockade of Fort Worth. The strikebreaker express would make its run on April 3. Jim Courtright, the man in charge of the other seven special deputies, would be riding shotgun with engineer Ed Smith in the cab of locomotive no. 54 as the train steamed through Cowtown to Alvarado.

But first that train had to pass through a railroad switch called “Buttermilk Junction”:

Buttermilk and Blood (Part 2): “For God’s Sake, Don’t Shoot”

Posts About Trains and Trolleys

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade

At that time, the familiar Katy Railroad was part of Jay Gould’s Missouri Pacific system. All the references to Missouri Pacific in the newspaper articles need to be interpreted as references to the Katy.

I noticed you did that parenthetically: Missouri Pacific (Katy).

I guess you could title a future follow-up article: “They’d Rather Fight Than Switch.”

There is a great hootenanny going on on Magnolia Street today. Clearly in remembrance of this event. Woooo woooooooo. Buttermilk Junction. What a great story. Union men and law dogs all shootin’ the place up. I was in the great GD strike of 1984. We got tear gassed by the fire department. Russ Bloxom of TV 5 got hit in the head by a bottle of beer. But nothing like this. Out, brothers, out.

Thanks, Earl. Ol’ Jim seemed always to be where the lead was flying.