He said he wanted to make his own way in the world, not live in the shadow of his famous father. In fact, sometimes it seemed that he spent his life trying to run out from under that big shadow cast by Sam Houston.

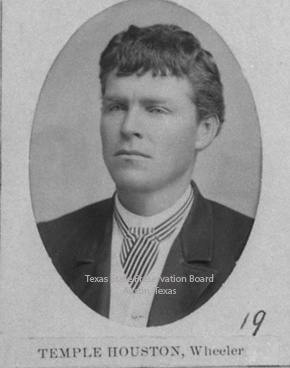

Temple Lea Houston was Sam Houston’s last child, born in 1860 (when Sam was sixty-seven), and the first child born in the Texas governor’s mansion. (Photo from Legislative Reference Library of Texas.)

Temple Lea Houston was Sam Houston’s last child, born in 1860 (when Sam was sixty-seven), and the first child born in the Texas governor’s mansion. (Photo from Legislative Reference Library of Texas.)

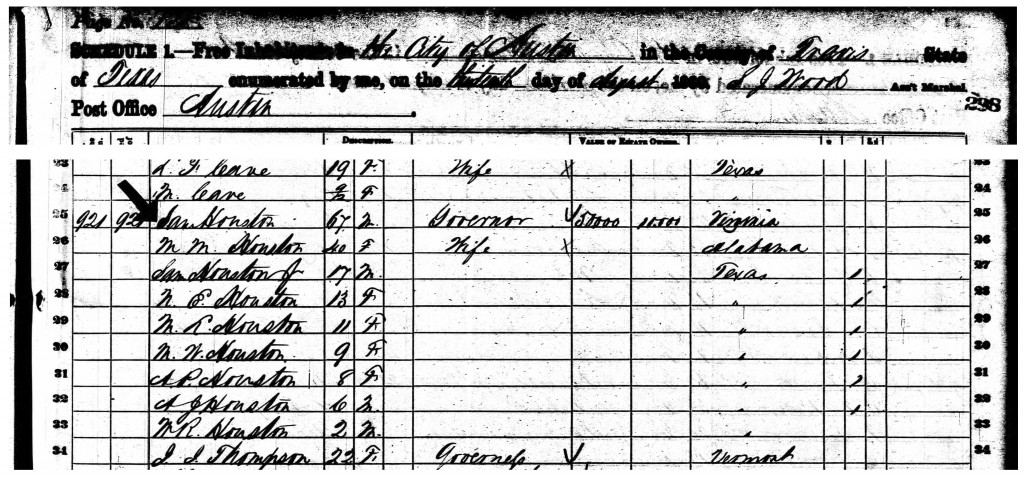

This is the census listing of the Sam Houston household at the governor’s mansion in August 1860. The day of the listing is difficult to read but appears to be “thirteenth.” If so, census taker Wood knocked on the door of the governor’s mansion the day after Temple Houston had increased the household by one, although the infant Temple is not listed in the census.

Sam Houston died when Temple was three, but Temple inherited his father’s sense of adventure. Temple joined a cattle drive at age thirteen, later worked on a Mississippi River steamboat.

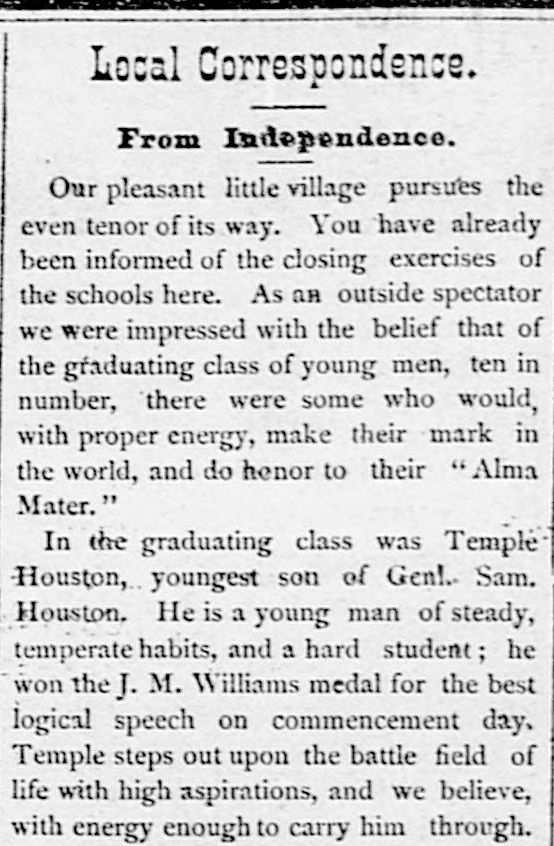

Temple Houston also inherited his father’s love of law and politics. Temple graduated from Baylor University in 1878 and stayed on to “read law.” Note that he won an award for oratory. Clip is from the June 28 Brenham Weekly Banner.

Temple Houston also inherited his father’s love of law and politics. Temple graduated from Baylor University in 1878 and stayed on to “read law.” Note that he won an award for oratory. Clip is from the June 28 Brenham Weekly Banner.

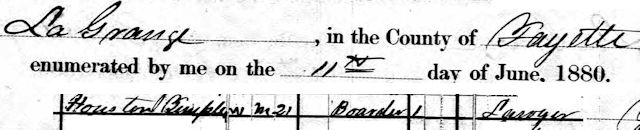

Indeed, Temple seemed driven to overachieve. He was admitted to the bar in 1880 and opened a practice in La Grange in Fayette County. At age twenty-one he was the youngest practicing attorney in Texas. He also started a newspaper in Brazoria. In 1882, at age twenty-two, he was appointed district attorney of the Thirty-Fifth Judicial District. And when he was elected a state senator in 1884 he became the youngest in Texas history at age twenty-four. The state Constitution requires a minimum age of twenty-six, but, hey, with the son of Sam Houston, who was counting? Temple Houston served four years in the Senate.

Indeed, Temple seemed driven to overachieve. He was admitted to the bar in 1880 and opened a practice in La Grange in Fayette County. At age twenty-one he was the youngest practicing attorney in Texas. He also started a newspaper in Brazoria. In 1882, at age twenty-two, he was appointed district attorney of the Thirty-Fifth Judicial District. And when he was elected a state senator in 1884 he became the youngest in Texas history at age twenty-four. The state Constitution requires a minimum age of twenty-six, but, hey, with the son of Sam Houston, who was counting? Temple Houston served four years in the Senate.

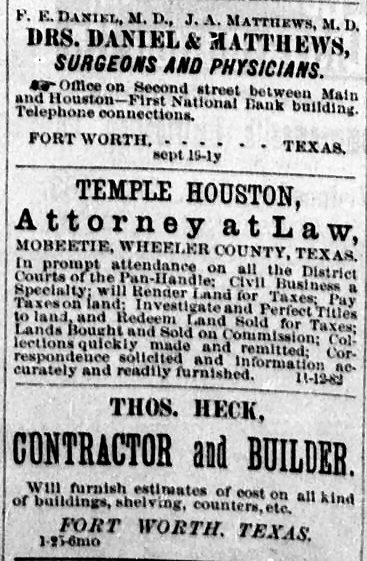

For several weeks in 1883 this classified ad ran in the Fort Worth Gazette. Wheeler County is in the Panhandle east of Amarillo.

For several weeks in 1883 this classified ad ran in the Fort Worth Gazette. Wheeler County is in the Panhandle east of Amarillo.

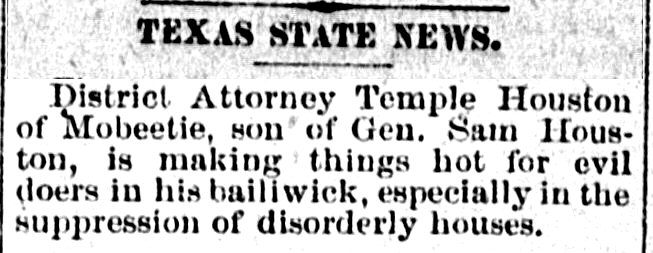

The appositive “son of Sam Houston” often followed Temple Houston’s name in print. The Gazette on December 8, 1883 reported that District Attorney Houston, then living in Mobeetie, was shutting down disorderly houses (brothels). But in 1899 he agreed to defend—on short notice—Minnie Stacey, a “soiled dove” who roosted at the Dew Drop Inn in Woodward, Oklahoma. Many trial attorneys to this day consider Temple’s extemporaneous closing argument to the jury—known as the “Soiled Dove Speech” or “Plea for a Fallen Woman”—to be a classic. The all-male jury quickly acquitted the woman by a unanimous verdict.

The appositive “son of Sam Houston” often followed Temple Houston’s name in print. The Gazette on December 8, 1883 reported that District Attorney Houston, then living in Mobeetie, was shutting down disorderly houses (brothels). But in 1899 he agreed to defend—on short notice—Minnie Stacey, a “soiled dove” who roosted at the Dew Drop Inn in Woodward, Oklahoma. Many trial attorneys to this day consider Temple’s extemporaneous closing argument to the jury—known as the “Soiled Dove Speech” or “Plea for a Fallen Woman”—to be a classic. The all-male jury quickly acquitted the woman by a unanimous verdict.

An extract of Houston’s closing argument: “Gentlemen of the jury: You heard with what cold cruelty the prosecution referred to the sins of this woman, as if her condition were of her own preference. The evidence has painted you a picture of her life and surroundings. Do you think that they were embraced of her own choosing? Do you think that she willingly embraced a life so revolting and horrible? Ah, no! Gentlemen, . . . Our sex wrecked her once pure life . . . and only in the friendly shelter of the grave can her betrayed and broken heart ever find the Redeemer’s promised rest.”

Like his father, Temple Houston was a big man. He wore his wavy hair shoulder length, dressed in a white Stetson hat, white vest, long black frock coat, rattlesnake-skin necktie. And like his father, Temple Houston became the stuff of myth: Temple Houston is said to have once cleared a courtroom during a trial when he suddenly drew his pistol and fired six shots—blanks—at the jury to make a point; he bested Billy the Kid in a shooting match; he dodged death when an assassin’s bullet struck a lawbook instead of Houston.

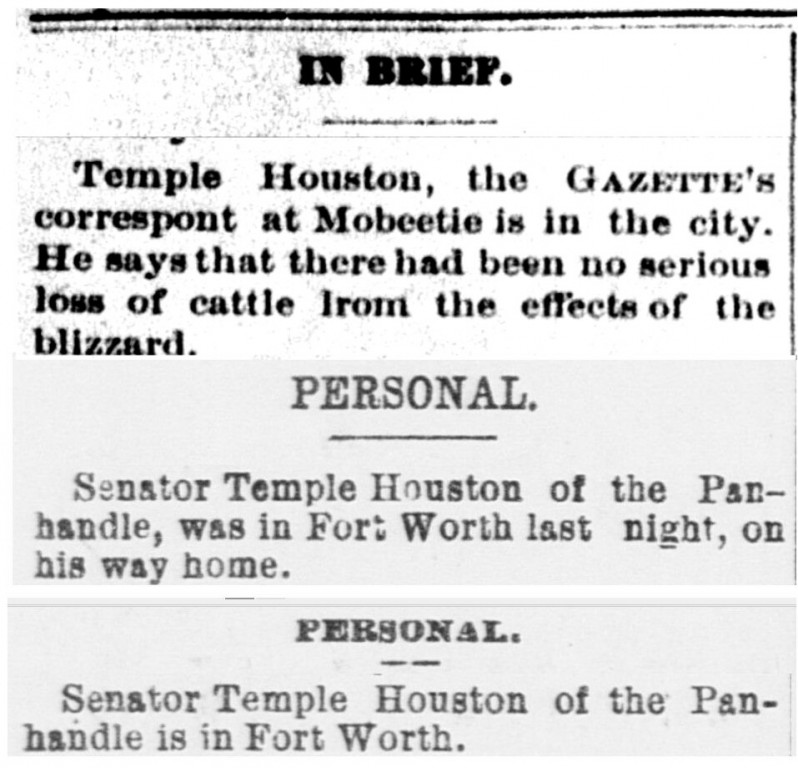

In 1887 the Fort Worth Gazette referred to Houston as a correspondent. He was in town often. Temple and Fort Worth banker Otho S. Houston, who in 1897 would be reported as an eyewitness during Airship April, were first cousins.

In 1887 the Fort Worth Gazette referred to Houston as a correspondent. He was in town often. Temple and Fort Worth banker Otho S. Houston, who in 1897 would be reported as an eyewitness during Airship April, were first cousins.

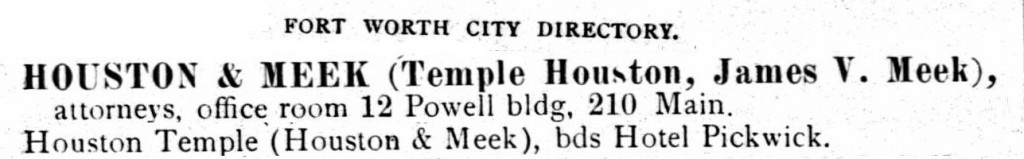

In fact, in 1891 Temple Houston moved to Fort Worth to practice law, staying at the Pickwick Hotel (where Sundance Square is today). He was active in the local Democratic Party. This clip is from the 1892 city directory.

In fact, in 1891 Temple Houston moved to Fort Worth to practice law, staying at the Pickwick Hotel (where Sundance Square is today). He was active in the local Democratic Party. This clip is from the 1892 city directory.

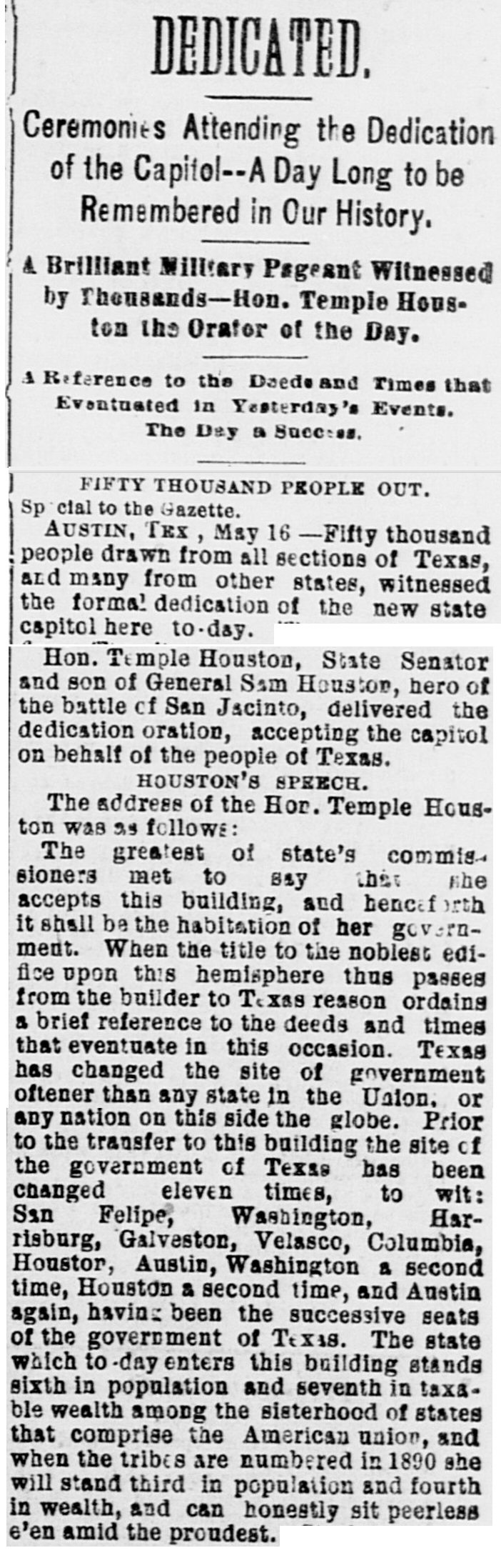

In 1888, when the new state Capitol was dedicated, Temple Houston delivered the “dedication oration,” accepting the new building on behalf of the people of Texas.

In 1888, when the new state Capitol was dedicated, Temple Houston delivered the “dedication oration,” accepting the new building on behalf of the people of Texas.

The first part of his speech is included in this clip from the May 17 Gazette.

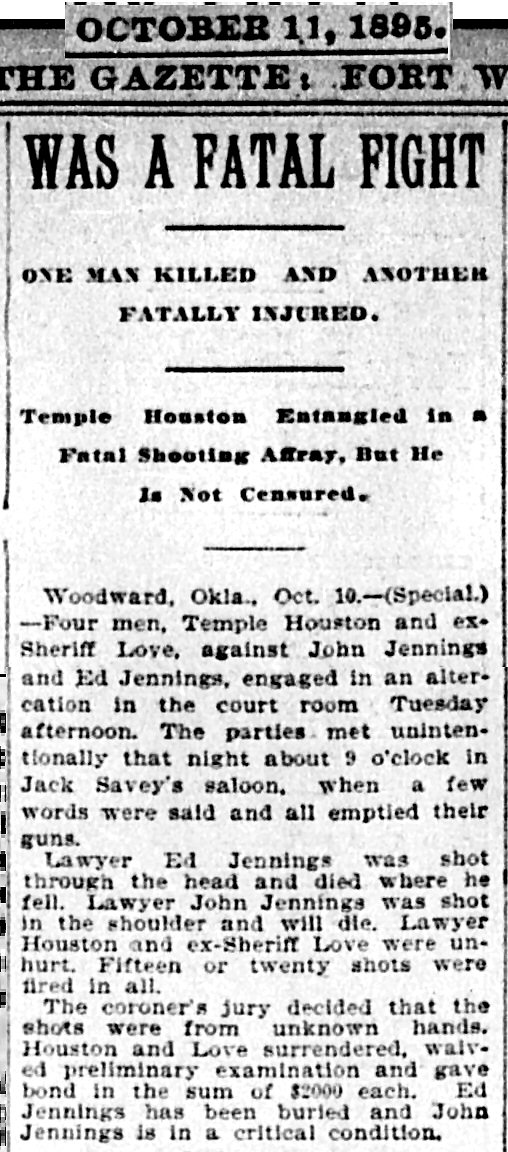

But Temple Houston’s life was bedeviled by confrontation. In 1895, when he was living in Oklahoma, the Gazette reported that he shot and killed fellow lawyer Ed Jennings. Ed’s brother John was wounded. Houston was acquitted after acting as his own counsel and pleading self-defense. Twenty witnesses testified that Ed Jennings had drawn first.

But Temple Houston’s life was bedeviled by confrontation. In 1895, when he was living in Oklahoma, the Gazette reported that he shot and killed fellow lawyer Ed Jennings. Ed’s brother John was wounded. Houston was acquitted after acting as his own counsel and pleading self-defense. Twenty witnesses testified that Ed Jennings had drawn first.

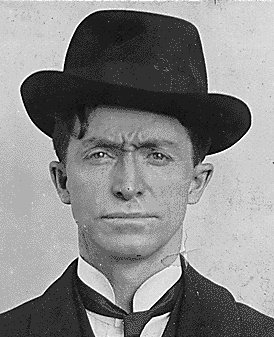

Ed and John Jennings were brothers of Al Jennings, who himself had an interesting resume: attorney, train robber, evangelist, and silent movie actor. After Al’s brother Ed was killed, Al had sworn to kill Temple Houston but was sent to prison before he got the chance. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Ed and John Jennings were brothers of Al Jennings, who himself had an interesting resume: attorney, train robber, evangelist, and silent movie actor. After Al’s brother Ed was killed, Al had sworn to kill Temple Houston but was sent to prison before he got the chance. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

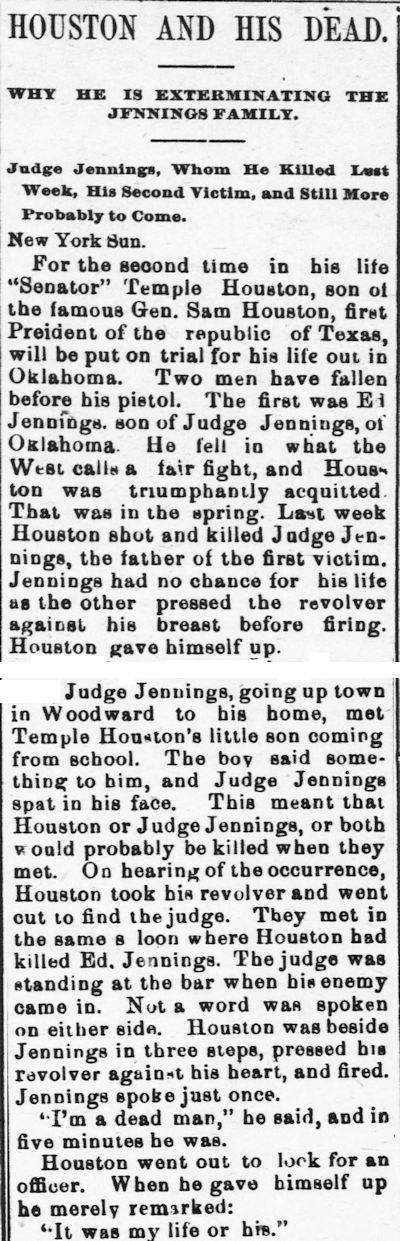

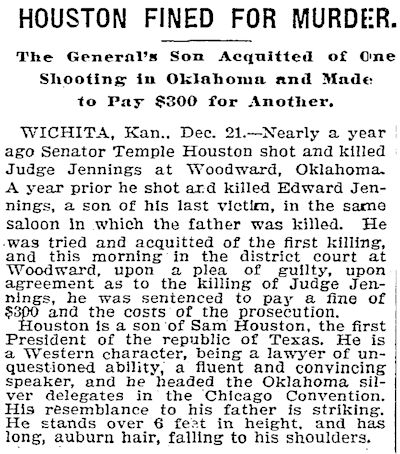

The Houston-Jennings family feud continued. One year later on November 12, 1896 the Charlotte Democrat reported that Houston had shot and killed Judge Jennings after the judge spat in the face of Houston’s son. Houston killed father Judge Jennings in the same saloon where Houston had killed son Ed Jennings.

The Houston-Jennings family feud continued. One year later on November 12, 1896 the Charlotte Democrat reported that Houston had shot and killed Judge Jennings after the judge spat in the face of Houston’s son. Houston killed father Judge Jennings in the same saloon where Houston had killed son Ed Jennings.

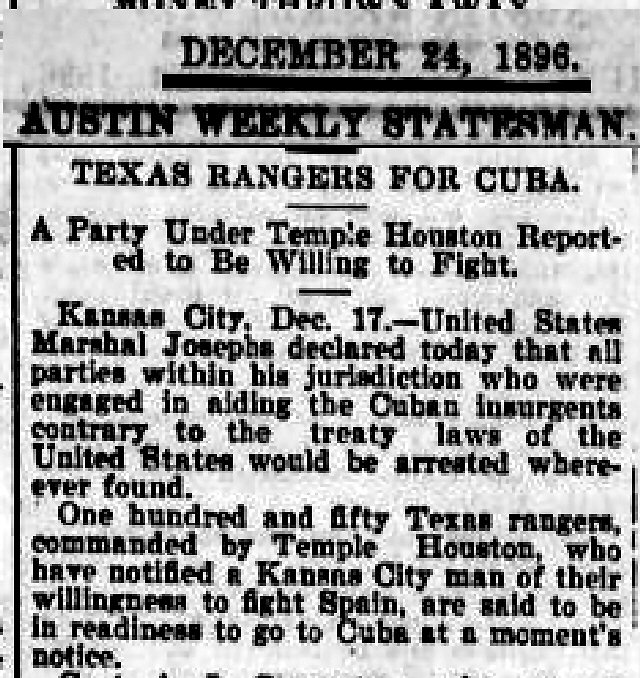

The next month Temple Houston announced that he was willing to go to Cuba to fight Spain.

The next month Temple Houston announced that he was willing to go to Cuba to fight Spain.

In 1897 “the son of Sam Houston” pleaded guilty and was fined $300 for killing Judge Jennings in 1896. Clip is from the December 22 New York Times.

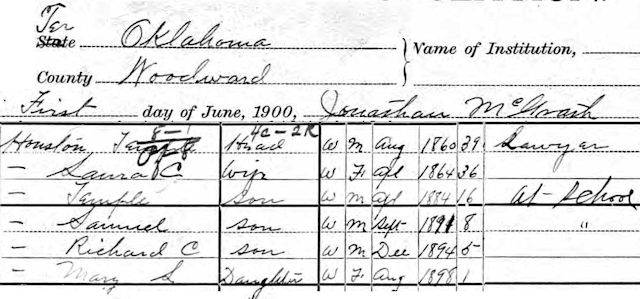

Temple Houston spent the final years of his life in Woodward, Oklahoma, where he had delivered his “Soiled Dove Speech” in 1899. Note that he had a son named “Samuel.”

Temple Houston spent the final years of his life in Woodward, Oklahoma, where he had delivered his “Soiled Dove Speech” in 1899. Note that he had a son named “Samuel.”

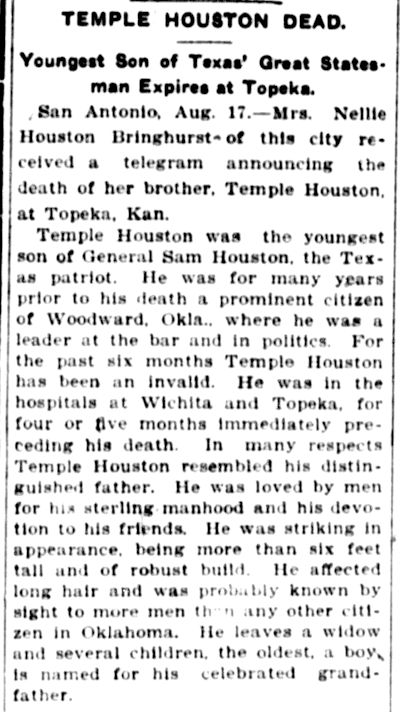

In 1904 Houston suffered a stroke and was invalided. He died on August 15, 1905. Forty-two years after Sam Houston died, Temple Houston, even in death, could not escape the label he had run from all his life: “son of General Sam Houston.” This clip is from the August 18 Bryan Morning Eagle.

In 1904 Houston suffered a stroke and was invalided. He died on August 15, 1905. Forty-two years after Sam Houston died, Temple Houston, even in death, could not escape the label he had run from all his life: “son of General Sam Houston.” This clip is from the August 18 Bryan Morning Eagle.

Temple Lea Houston is buried in Woodward, Oklahoma. He was forty-five years old.

Temple Lea Houston is buried in Woodward, Oklahoma. He was forty-five years old.

Temple Houston would kick the dung out of Rafael Cruz and his lying cabal of foreign insurgents!

Great story. That last line sent chills down my spine.

Thanks, Ramiro. We had to know that no son of Sam was going to lead a quiet life. I have never seen the short-lived TV series based (loosely, I am sure) on his life.