You don’t have to be an experienced explorer of cemeteries to notice something different about this one.

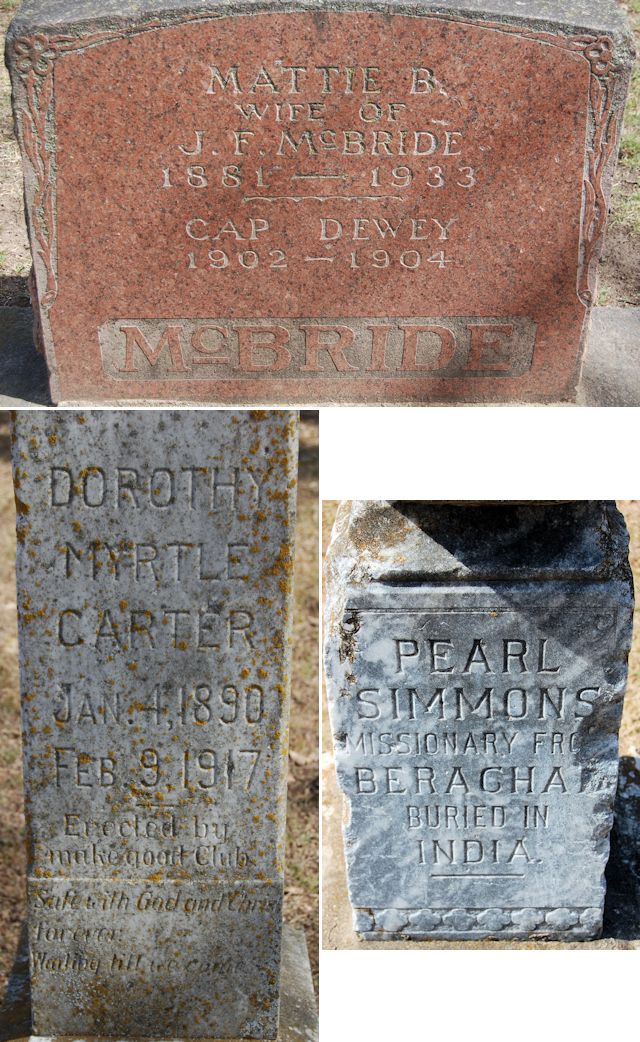

Of its eighty or so tombstones, only three are vertical (and one of the three memorializes a woman buried elsewhere):

Of its eighty or so tombstones, only three are vertical (and one of the three memorializes a woman buried elsewhere):

Most of its tombstones are flat—small bricks of marble set in concrete squares:

Most of its tombstones are flat—small bricks of marble set in concrete squares:

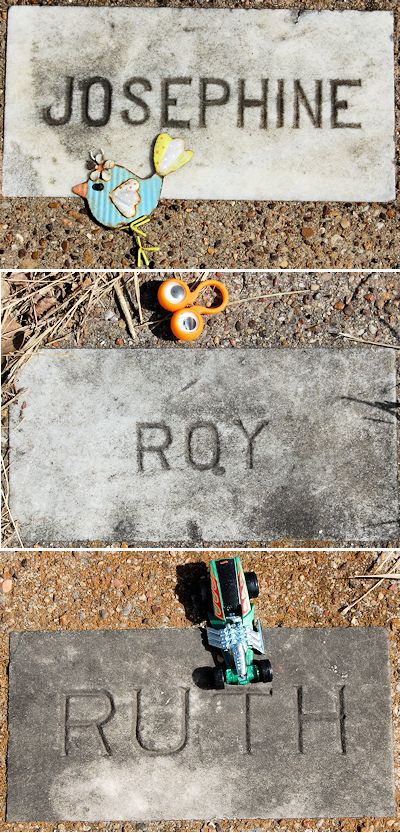

Many of its tombstones bear only a first name.

Many of its tombstones bear only a first name.

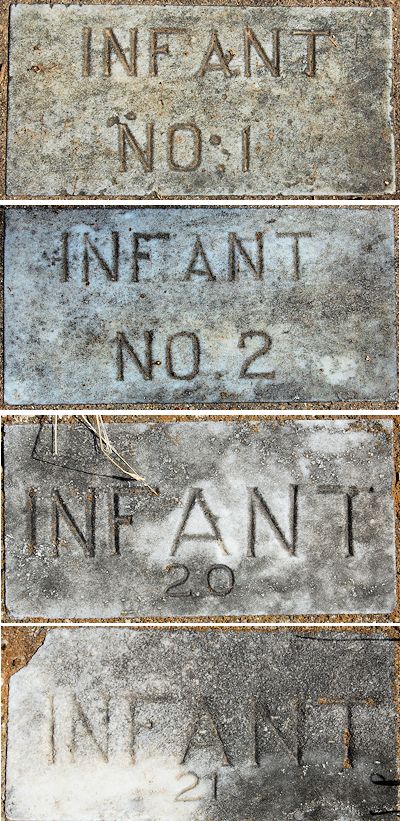

Some bear only the word infant and a number.

Some bear only the word infant and a number.

And one bears neither name nor number.

And one bears neither name nor number.

This cemetery, located in a corner of Doug Russell Park on the edge of the University of Texas at Arlington campus, is the most visible reminder of an example of a social institution that was common early in the twentieth century: the rescue home.

The Berachah Industrial Home for the Redemption of Erring Girls was one of more than two hundred rescue homes in America during the Third Great Awakening, a period of religious activism led by churches and organizations such as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and Young Women’s Christian Association. Such reformers numbered among their missions (1) shutting down gambling houses, saloons, and brothels and (2) “redeeming” young women who had “fallen from grace”—especially prostitutes and more especially prostitutes who were pregnant.

The task of “redeeming” such “fallen women” fell to rescue homes.

Most large cities in Texas had a rescue home.

Reverend James Toney Upchurch founded three of them.

Upchurch was born in 1870 in Bosqueville outside Waco. Upchurch came by his “come to Jesus” moment the hard way: He had been a hard-drinkin’, hard-dancin’ atheist until one night he was invited to attend a revival instead of a dance. He attended, was converted, joined the Methodist church, and—with the zeal of a convert—began conducting religious services in jails and in the Reservation, which was Waco’s vice district.

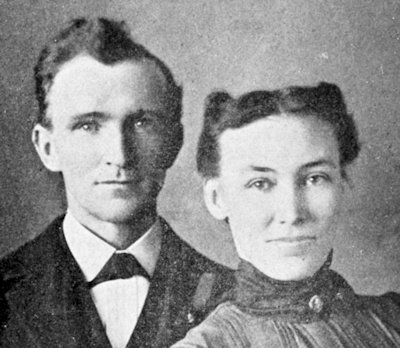

In 1892 Upchurch married Maggie May Adams, and together they ministered to “fallen women,” especially pregnant prostitutes. The life of prostitutes was, in the words of Thomas Hobbes, “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Many lives ended by suicide, drug overdose, inept abortion.

In 1894 the Upchurches founded the Berachah Rescue Home in Waco. (Berachah is Hebrew for “blessing”; 2 Chronicles 20:26). (Photo from Berachah Home Collection, Special Collections, University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

But religious leaders in Waco disapproved of the Upchurches’ efforts to redeem prostitutes, especially Reverend Upchurch’s policy of insisting that prostitutes not put their baby up for adoption. Upchurch’s view was that women who give away their baby are attempting to “cover up their dark sins of social impurity.”

The Upchurches, finding themselves outcasts in Waco, closed their rescue home there and moved to Dallas, where in 1899 they opened a rescue home in Oak Cliff.

But by 1901 Upchurch looked to the west and had a new vision. Both Dallas and Fort Worth had vice districts. A rescue home located midway could take in fallen women of both cities and yet, in those horse-and-buggy days, harbor those women well away from the temptations of the vice districts: Hell’s Half Acre in Fort Worth and Frogtown and Boggy Bayou in Dallas.

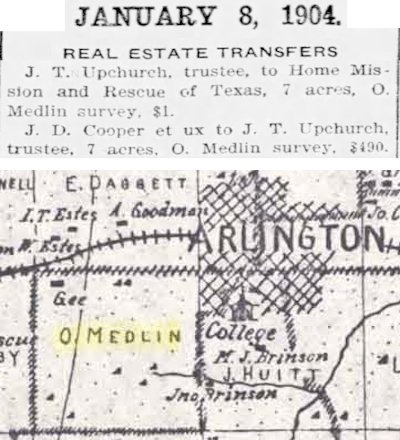

Upchurch began to buy land just outside the Arlington city limits. The land had once been the Peters Colony land grant of William Owen Medlin (as in the Arlington street). Upchurch bought most of the land from James D. Cooper (as in the Arlington street).

Upchurch began to buy land just outside the Arlington city limits. The land had once been the Peters Colony land grant of William Owen Medlin (as in the Arlington street). Upchurch bought most of the land from James D. Cooper (as in the Arlington street).

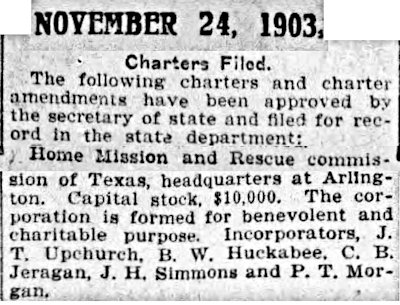

By 1903 Upchurch had enough land (twenty-seven acres) and enough money to open his Berachah Industrial Home for the Redemption of Erring Girls. (Founded a year earlier was adjacent Carlisle Military Academy, which would evolve into UTA.)

By 1903 Upchurch had enough land (twenty-seven acres) and enough money to open his Berachah Industrial Home for the Redemption of Erring Girls. (Founded a year earlier was adjacent Carlisle Military Academy, which would evolve into UTA.)

The Berachah rescue home, in the beginning consisting of a single building, opened in May 1903. (Photo from Berachah Home Collection, Special Collections, University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

The mission of the home, according to Upchurch, was to restore “fallen women” to “honorable lives.”

He said: “Until a few years ago it was not generally believed that a fallen woman could be redeemed to a life of purpose, but it is now becoming an established fact that the grace of God can restore fallen womanhood as easily as it can restore fallen manhood.”

Upchurch lamented the double standard that failed to condemn a pregnant woman’s unscrupulous lover or white slave trader and yet stigmatized the pregnant woman.

He preached that “it was unfair to deal with two sinners so differently as to send one to Congress and one to perdition.”

In Arlington Upchurch continued his policy of insisting that unwed mothers keep their baby.

The Berachah home took in fallen women but only one color of fallen women: white. Megan Martin Joblin in her 2018 master’s thesis on the home calls Upchurch “a clear supporter of the Ku Klux Klan” (not unusual for the time and place).

The first “fallen woman” to enter the home was named “Dilly.” Her son was the first child born at the home. Fittingly he was named “Alpha.”

Dilly was also the home’s first success story: She stayed on at the home as a midwife, helping to deliver the residents’ babies.

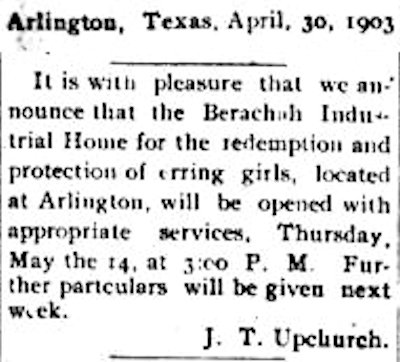

And in 1904 the first person to be buried in Berachah Cemetery was Eunice Bell, age twenty-six. (Photo from Berachah Home Collection, Special Collections, University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

And in 1904 the first person to be buried in Berachah Cemetery was Eunice Bell, age twenty-six. (Photo from Berachah Home Collection, Special Collections, University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

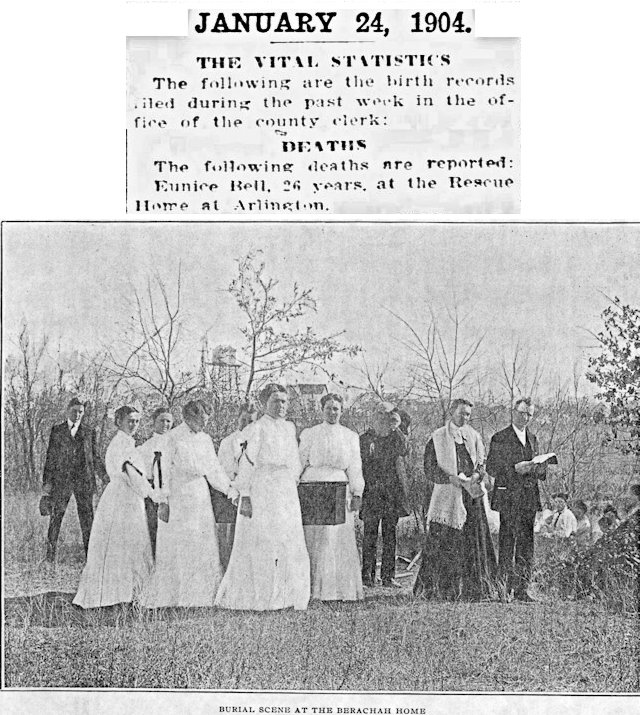

In time the Berachah home grew to sixty-seven acres. The home had an infirmary, nursery, laundry, tabernacle, chapel, dormitories, school, dining hall, and print shop.

Residents maintained an orchard and garden, canned their own fruits and vegetables. Residents also kept chickens and cows. Residents brought in extra revenue by picking cotton on area farms. (Photo from Berachah Home Collection, Special Collections, University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

The word “Industrial” in the name of the home was perhaps overblown. The home had a small wood-frame “factory” where residents made handkerchiefs to learn a skill and to produce income for the home.

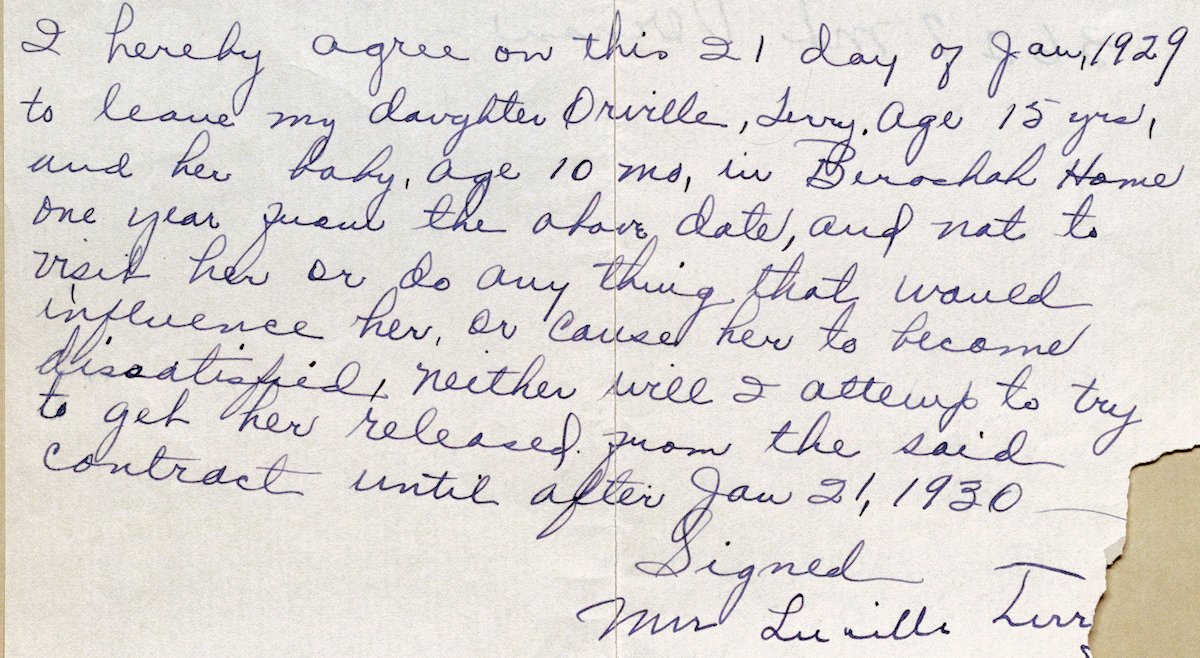

When a girl enrolled in the home she or her parents signed a contract that required the girl to remain at the home for one year after the birth of her child.

When a girl enrolled in the home she or her parents signed a contract that required the girl to remain at the home for one year after the birth of her child.

Life at the home was regimented.

Upon arrival girls dropped their jewelry into a wooden keg.

Residents wore their hair pulled back in a bun.

The home did not allow residents to use caffeine, tobacco, or alcohol, to eat pork, dance, swim with males, or use the telephone on Sundays.

The home provided room and board and kept the residents busy: religious instruction, vocational training (printing, domestic service, nursing, stenography, sewing), school, and work. Residents were taught how to care for their newborn child.

After staying in the home for a year, a resident was considered to be “redeemed” and fit to be released back into society. (Photo from Berachah Home Collection, Special Collections, University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

A photo from about 1905. Upchurch is the man on the left. (Photo from Berachah Home Collection, Special Collections, University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

Religious rallies were held in the home’s Whitehill Tabernacle, named for a donor. (Photo from Berachah Home Collection, Special Collections, University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

Outside a dormitory. (Photo from Berachah Home Collection, Special Collections, University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

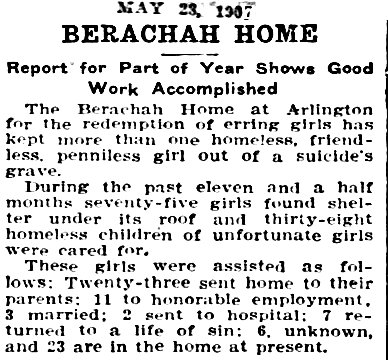

In 1907 the Telegram reported on the home’s work:

In 1907 the Telegram reported on the home’s work:

“The Berachah Home at Arlington for the redemption of erring girls has kept more than one homeless, friendless, penniless girl out of a suicide’s grave.

“During the past eleven and a half months seventy-five girls found shelter under its roof and thirty-eight homeless children of unfortunate girls were cared for.

“These girls were assisted as follows: Twenty-three sent home to their parents; 11 to honorable employment, 3 married; 2 sent to hospital; 7 returned to a life of sin; 6, unknown, and 23 are in the home at present.”

In addition to prostitutes, the Berachah home enrolled victims of domestic abuse, abandonment, incest, and rape—all viewed as “fallen” despite their victimization.

Berachah workers recorded the human ebb and flo at the home in ledgers. For example, in early 1916 the registrar wrote these entries:

“Jan. 7. Ran away to Fort Worth, Josephine B. and Pearl N.

“Jan. 10. Miss Eva M., aged 22, betrayed by sweetheart. Promise of marriage. Expectant mother since latter part of July 1915. Agrees to stay until babe is one year old. Seems an agreeable and likely girl.

“Jan. 18. Mrs. Birdie G., deceived by sweetheart. Promise of marriage. Expectant mother since early June. Agrees to stay.

“Jan. 22. Jessie C. dismissed from home. Would not be content here.

“Feb. 19. Died to Miss Lillian H., little Raenette, 8 1/2 mons. old — Apparently consumption.”

The home claimed that 75 percent of its residents who stayed “any length of time” became “redeemed.”

But life at Berachach did not suit all residents. Some residents chafed at the home’s rules. The home’s religious messaging stuck in the craw of others. Some prostitutes returned to their former profession, which paid better than the vocations they were taught at the home.

Residents who did not stay at the home a full year were considered to be “dishonorably discharged” back into a life of sin.

But others were contented. One Berachah girl wrote, “When I first saw Berachah I thought it was the most beautiful place I had ever seen. After being told it was a place where broken hearts and blighted lives were made happy, I rejoiced.” (Photo from Berachah Home Collection, Special Collections, University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

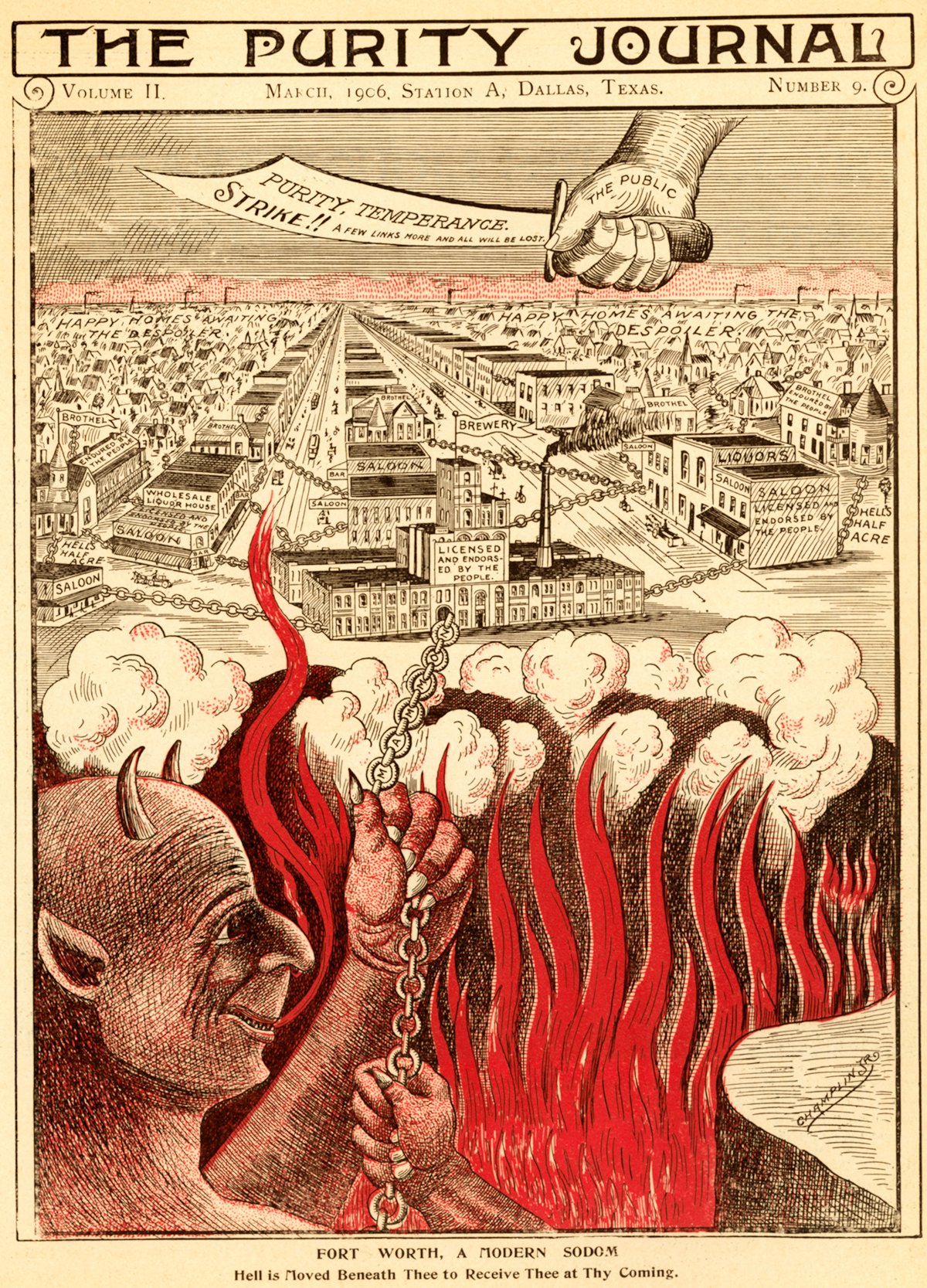

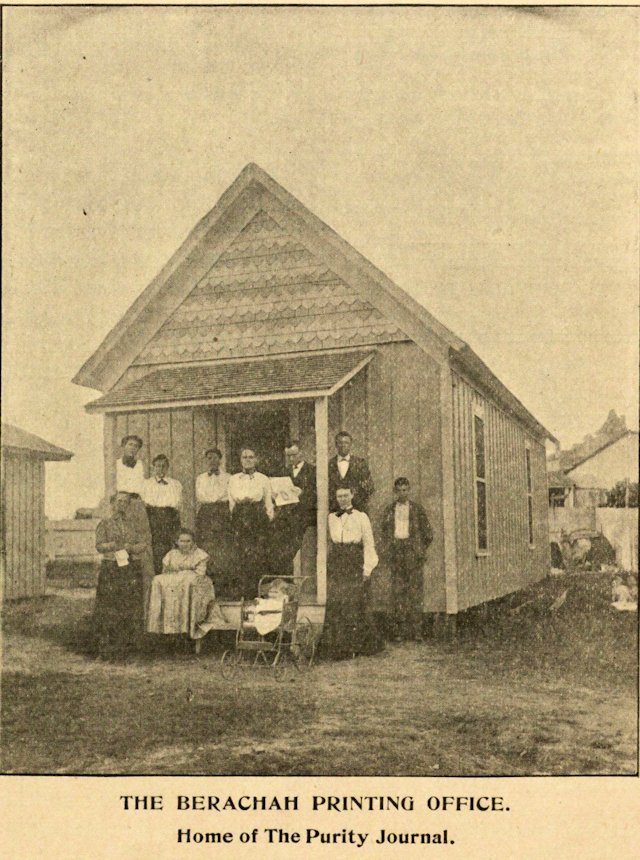

The Berachah home did not collect any money from its residents. In addition to the sale of handkerchiefs, the home derived revenue from the sale of Upchurch’s publications, including his Purity Journal and Purity Crusader. In these newsletters the home’s residents detailed their stories of ruin and redemption. Upchurch also used the newsletters to solicit donations. The newsletters had subscribers in most states and several foreign countries.

“Fort Worth, A Modern Sodom”: This cover of a 1906 issue of Purity Journal singled out Hell’s Half Acre’s saloons, brothels, and Texas Brewing Company as “endorsed by the people” who live in “happy homes awaiting the despoiler.” (Photo from Berachah Home Collection, Special Collections, University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

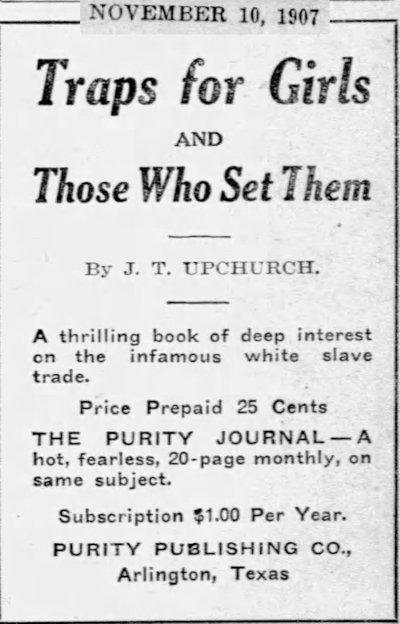

Upchurch wrote two booklets—Traps for Girls and Those Who Set Them and Black Slavery 1860 Versus White Slavery 1912—about the danger of white slavery.

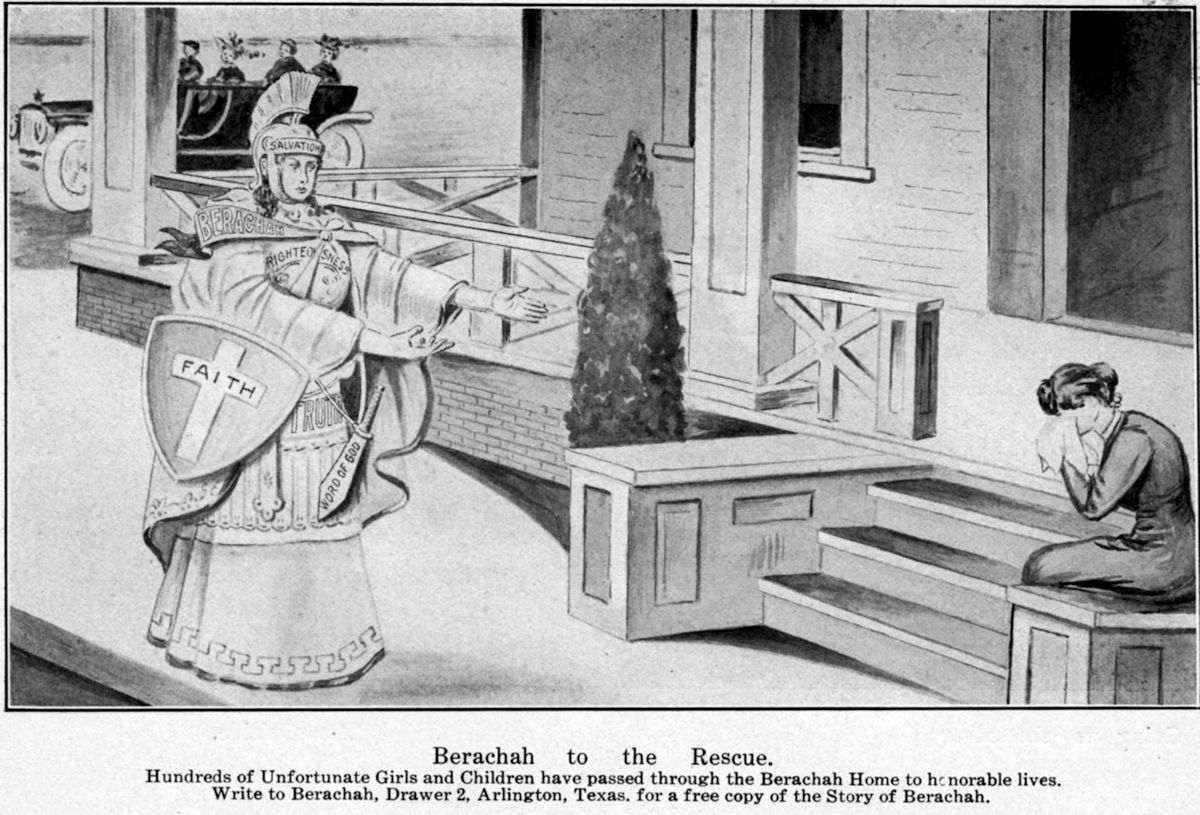

The 1912 image portrays an angel (outfitted in the helmet of Salvation, breastplate of Righteousness, sash of Berachah, shield of Faith, belt of Truth, and sword of the Word of God) reaching out to a weeping woman. (Photo from Berachah Home Collection, Special Collections, University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

Upchurch’s publications were printed in the home’s print shop, operated by residents. (Photo from Berachah Home Collection, Special Collections, University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

Upchurch’s publications were printed in the home’s print shop, operated by residents. (Photo from Berachah Home Collection, Special Collections, University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

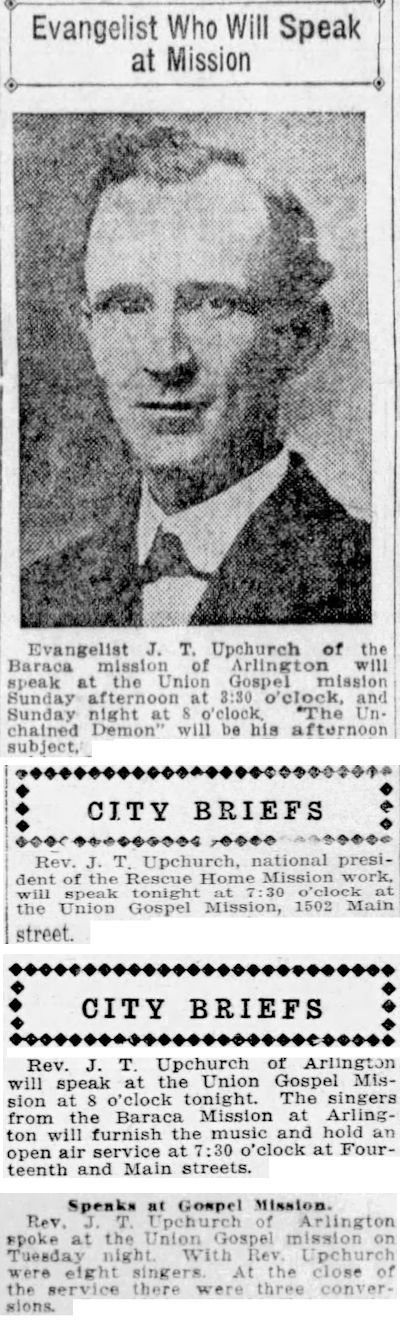

When J. T. Upchurch was not writing or raising money, he was preaching. He often went into the Acre to preach at the Union Gospel Mission.

When J. T. Upchurch was not writing or raising money, he was preaching. He often went into the Acre to preach at the Union Gospel Mission.

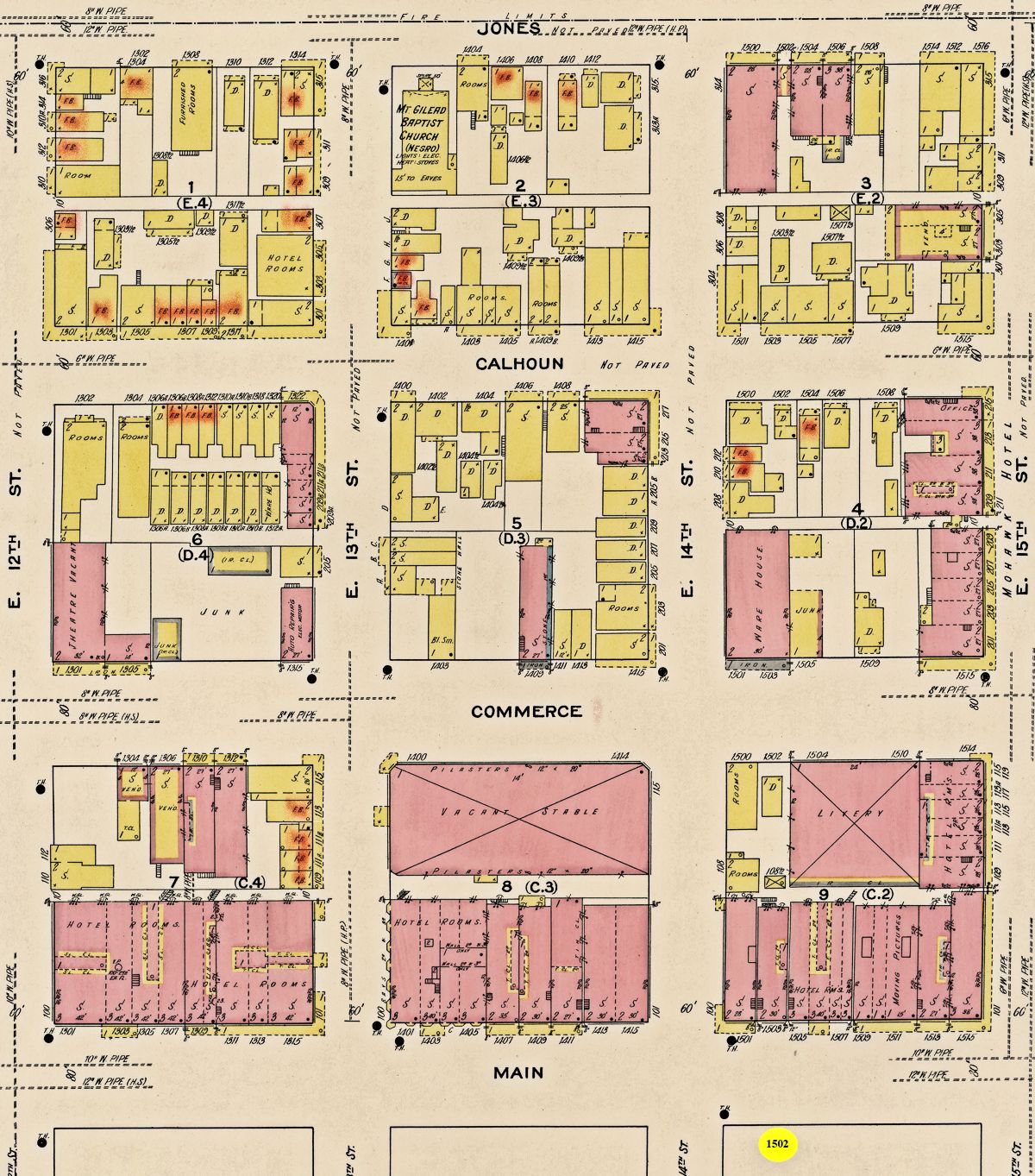

The mission was located at 1502 Main Street (yellow circle on map). In 1911 twenty-seven “female boardinghouses” (red-highlighted “FB”s on map), a euphemism for “brothel,” were located within three blocks of the mission.

Upchurch also traveled around the country preaching and preached on the radio.

He also promoted the home with the all-girl Berachah Band, which gave concerts across the country. A Berachah quartet sang at local revivals and church services.

One member of that quartet was Pearl Simmons (see photo above). Her great-nephew writes: “She was orphaned when a teenager and became desperate and involved in prostitution in Dallas. The Berachah organization brought her to their home in Arlington. She became part of their famous lady quartet visiting churches and revivals. She went to India as a missionary and died from smallpox” in 1912 at age twenty-eight.

Upchurch wrote of Pearl Simmons: “She entered the home despised and rejected by society but was tenderly pointed to Him who came to seek and save that which was lost. . . . He pardoned her sins, sanctified her, and called her to work for Him in faraway India.”

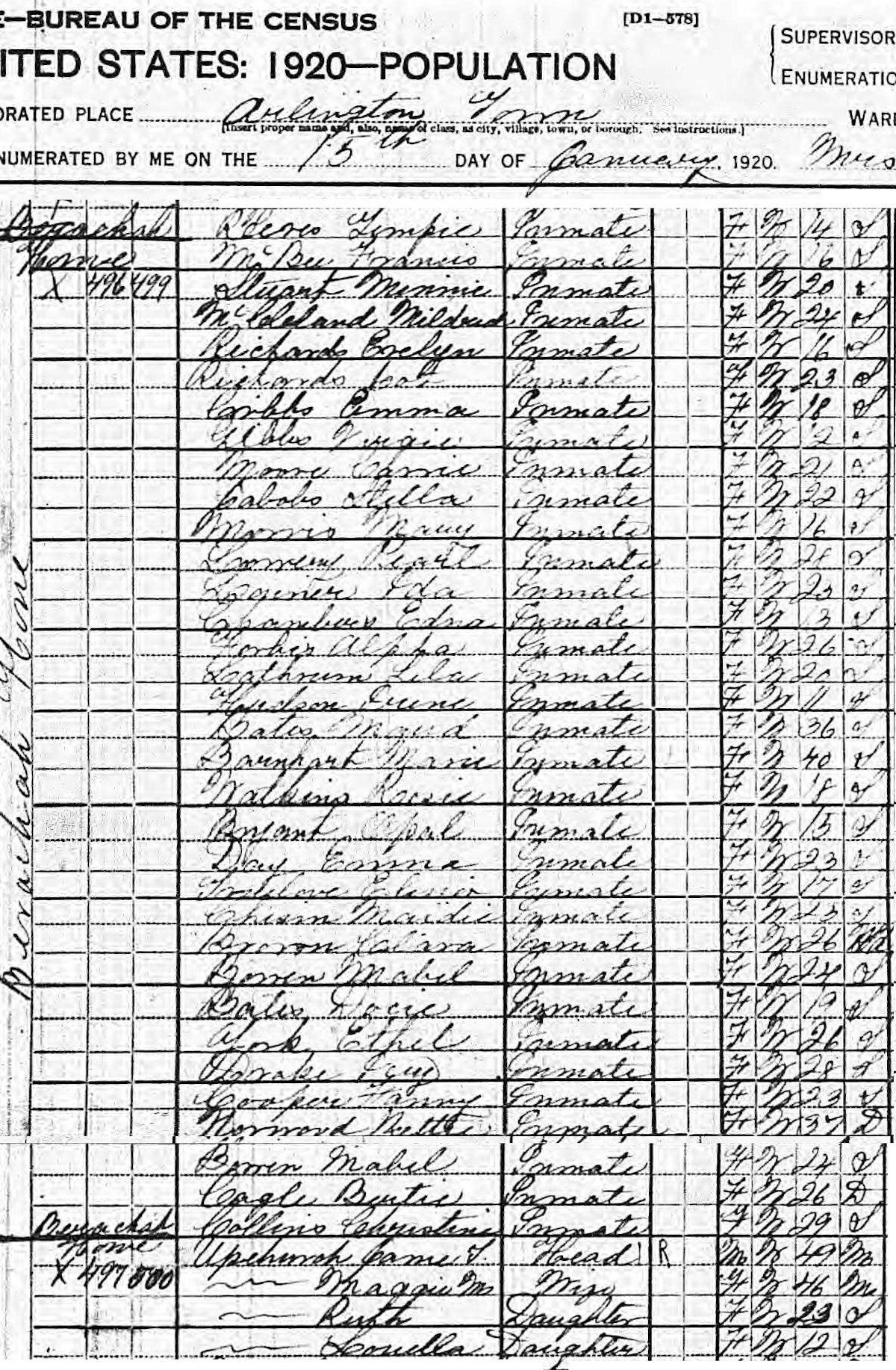

The 1920 census enumerated thirty-four Berachah “inmates” between the ages of eleven and forty.

The 1920 census enumerated thirty-four Berachah “inmates” between the ages of eleven and forty.

By 1924 the home had admitted 1,321 girls and their babies.

But the home closed in 1935. Researchers have cited these factors: Upchurch’s failing health, the Great Depression, and competition from the Edna Gladney home.

But the home closed in 1935. Researchers have cited these factors: Upchurch’s failing health, the Great Depression, and competition from the Edna Gladney home.

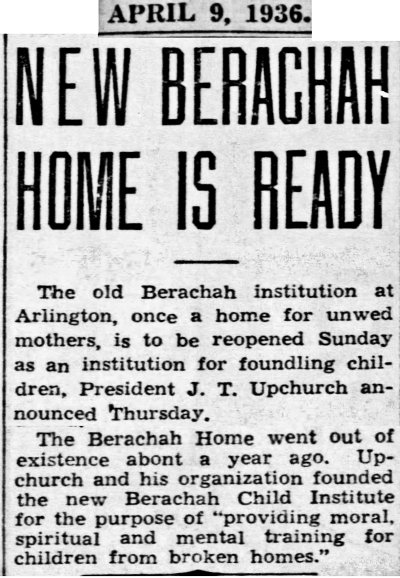

In 1936 the Upchurches’ daughter and son-in-law reopened the home as the Berachah Child Institute, which operated as something that J. T. Upchurch had resisted for forty years: an orphanage and adoption agency.

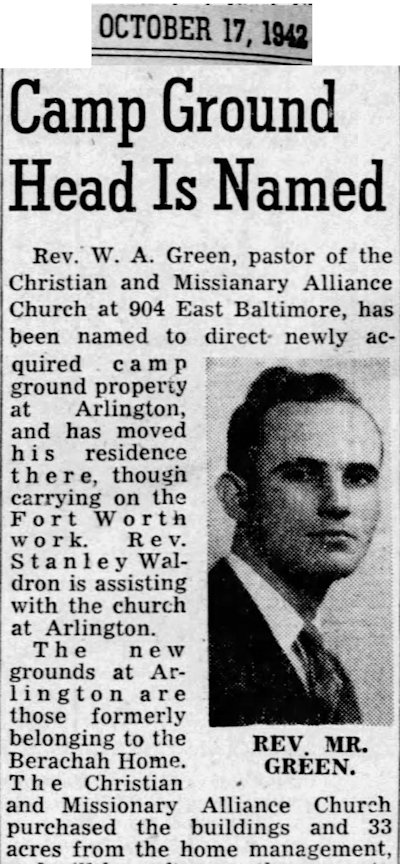

The institute lasted only until 1942.

The institute lasted only until 1942.

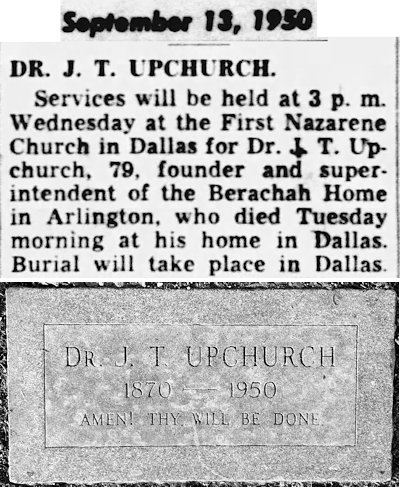

In 1950 James Toney Upchurch died in Dallas.

In 1950 James Toney Upchurch died in Dallas.

In 1963 Arlington State College (now the “University of Texas at Arlington”) and the city of Arlington acquired the Berachah campus.

Today only the Berachah home’s cemetery remains, like some sad nursery in eternity. (UTA’s Berachah Home Collection contains photos, journals, ledgers, and other printed relics.)

Today only the Berachah home’s cemetery remains, like some sad nursery in eternity. (UTA’s Berachah Home Collection contains photos, journals, ledgers, and other printed relics.)

Most of the cemetery’s eighty graves are those of children. Because of the stigma attached to unwed motherhood at the time, surnames were not included on most tombstones. Contemporary visitors to the cemetery have placed toys on some infants’ tombstones. Some researchers have attributed many of the infant deaths to measles in 1914-1915, but a woman who worked at the home disagreed. She recalled in 1993: “It was pure lack of care. They [Berachah workers] never called a doctor for anything except delivery of the babies.”

Most of the cemetery’s eighty graves are those of children. Because of the stigma attached to unwed motherhood at the time, surnames were not included on most tombstones. Contemporary visitors to the cemetery have placed toys on some infants’ tombstones. Some researchers have attributed many of the infant deaths to measles in 1914-1915, but a woman who worked at the home disagreed. She recalled in 1993: “It was pure lack of care. They [Berachah workers] never called a doctor for anything except delivery of the babies.”

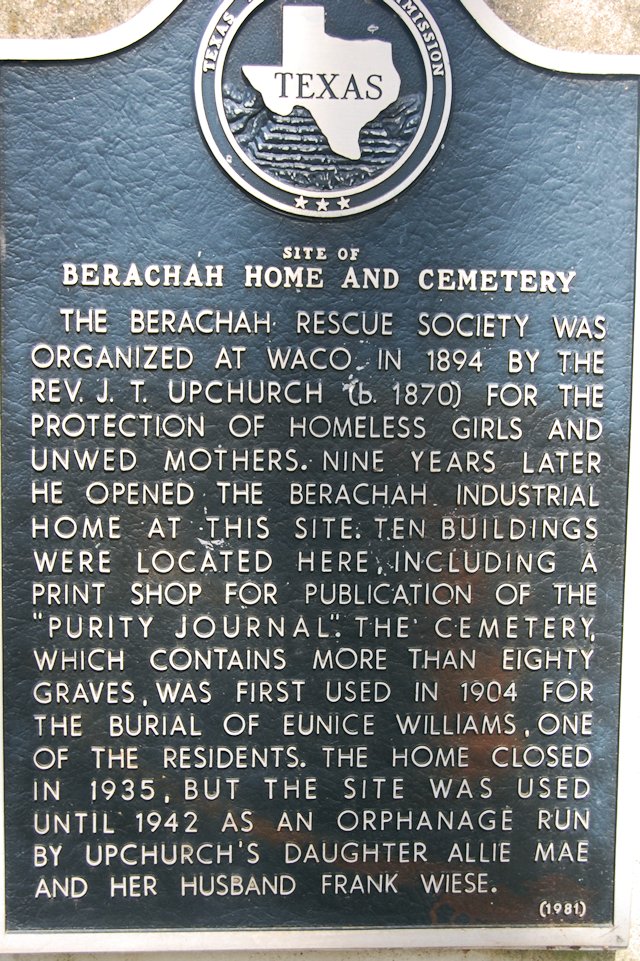

In 1981 the cemetery received a state historical marker.

In 1981 the cemetery received a state historical marker.

A marker near the cemetery entrance commemorates Berachah founder James Toney Upchurch, who sought to make “a place where broken hearts and blighted lives were made happy.”

A marker near the cemetery entrance commemorates Berachah founder James Toney Upchurch, who sought to make “a place where broken hearts and blighted lives were made happy.”