On the North Side, south of what is left of the Swift packing plant, jutting out of the embankment over Marine Creek is a horizontal iron pipe that seems to aim at downtown like a cannon.

Indeed, that “cannon” may have fired the first round at the city of Fort Worth in an early war over pollution in Texas.

Indeed, that “cannon” may have fired the first round at the city of Fort Worth in an early war over pollution in Texas.

If that supposition is true, that pipe is a remnant of early sewage treatment in Fort Worth.

The history of sewage treatment in Fort Worth is a story of frontier pragmatism, advances in science, changes in domestic life, politickin’, and, of course, good ol’ Cowtown-Big D fussin’ ’n’ feudin’.

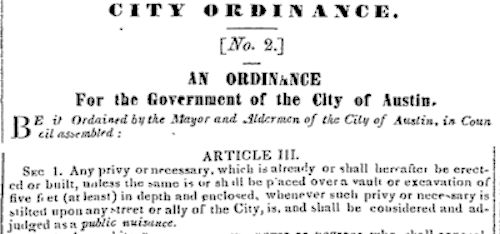

In the early days of Fort Worth, as elsewhere on the frontier, toilet facilities were plentiful. In fact, there was a toilet behind every tree. But soon, much to the relief of arborists, came such advances as chamber pots, outhouses, and cesspools (primitive septic tanks). For example, on March 31, 1855 the Texas State Gazette in Austin printed a city ordinance regulating privies. (A “necessary” was a privy or outhouse.)

In the early days of Fort Worth, as elsewhere on the frontier, toilet facilities were plentiful. In fact, there was a toilet behind every tree. But soon, much to the relief of arborists, came such advances as chamber pots, outhouses, and cesspools (primitive septic tanks). For example, on March 31, 1855 the Texas State Gazette in Austin printed a city ordinance regulating privies. (A “necessary” was a privy or outhouse.)

Until cisterns (receptacles for holding rain water), artesian wells, and—in 1882—a municipal waterworks came along, the unfiltered Trinity River was Fort Worth’s main source of drinking water. It was not uncommon for cities located on a river to use that river as both water fountain and cesspool. Fort Worth was no exception. People (and livestock) drank from the Trinity; people bathed themselves and their horses in it, dumped their sewage into it.

In the mid-1800s people did not have today’s fuller understanding of pathology. Some scientists believed that moving water—such as river water—purifies itself within a few miles. Thus, moving water polluted by raw sewage, the thinking was, is purified naturally as the water moves downstream.

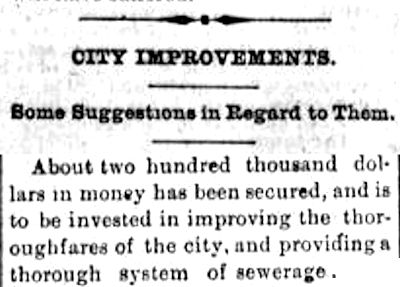

On the other hand, people did have enough understanding of pathology to know that standing water is a health hazard. So, early in 1883 the Fort Worth city council voted to pave its two main streets—Main and Houston—from the courthouse to the Texas & Pacific tracks—a distance of one mile—and to install a “thorough system of sewerage” on those two streets. That system was just gutters or other conduits to channel standing water from the streets down to the river. It was not—as we think of it today—a network of pipes and pumps channeling human waste to a treatment plant. (The city council in 1883 debated the choice of wood blocks or stone to pave Main and Houston. Stone, being cheaper, was chosen.) Clip is from the February 5, 1883 Daily Democrat.

On the other hand, people did have enough understanding of pathology to know that standing water is a health hazard. So, early in 1883 the Fort Worth city council voted to pave its two main streets—Main and Houston—from the courthouse to the Texas & Pacific tracks—a distance of one mile—and to install a “thorough system of sewerage” on those two streets. That system was just gutters or other conduits to channel standing water from the streets down to the river. It was not—as we think of it today—a network of pipes and pumps channeling human waste to a treatment plant. (The city council in 1883 debated the choice of wood blocks or stone to pave Main and Houston. Stone, being cheaper, was chosen.) Clip is from the February 5, 1883 Daily Democrat.

Grocer C. W. Slattery in his ad in the April 6, 1883 Daily Democrat applauded the city’s progress. And well he should: His store was located on Main—one of the two streets to receive the improvements.

Grocer C. W. Slattery in his ad in the April 6, 1883 Daily Democrat applauded the city’s progress. And well he should: His store was located on Main—one of the two streets to receive the improvements.

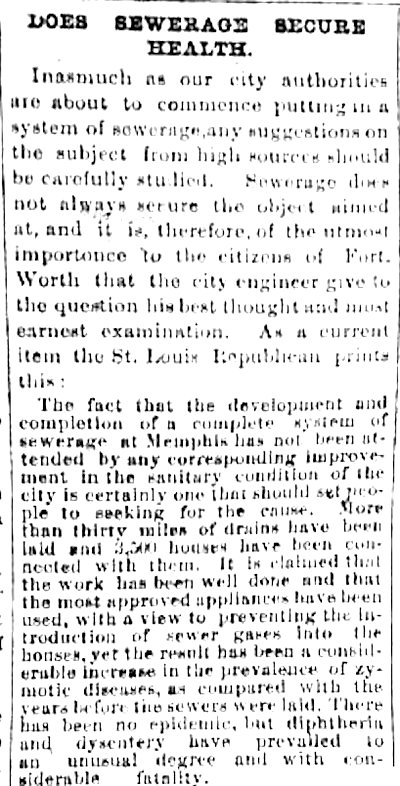

But on January 30, 1883 the Daily Democrat wondered aloud if a sewage system actually secures health. The Democrat reprinted an article from the St. Louis Republican that reported that installation of a sewage system in Memphis had created more health problems than it had prevented.

But on January 30, 1883 the Daily Democrat wondered aloud if a sewage system actually secures health. The Democrat reprinted an article from the St. Louis Republican that reported that installation of a sewage system in Memphis had created more health problems than it had prevented.

But by August 25, 1883 the Democrat was won over to the health benefits of a sewage system, lamenting the slow implementation of Fort Worth’s system and attributing sickness to “lack of sewerage.”

But by August 25, 1883 the Democrat was won over to the health benefits of a sewage system, lamenting the slow implementation of Fort Worth’s system and attributing sickness to “lack of sewerage.”

By 1886 some Fort Worth homes had indoor plumbing (water closets) connected to city sewer pipes. On December 16, 1886 the Democrat printed suggestions by the chairman of the board of health regarding installation of a water closet in homes. But even if a water closet was connected to the city sewer system, that system merely channeled waste—untreated—from house to river.

By 1886 some Fort Worth homes had indoor plumbing (water closets) connected to city sewer pipes. On December 16, 1886 the Democrat printed suggestions by the chairman of the board of health regarding installation of a water closet in homes. But even if a water closet was connected to the city sewer system, that system merely channeled waste—untreated—from house to river.

If a house had no “system of sewerage,” the health board chairman recommended a dry-earth closet (a toilet whose medium was dirt instead of water, also called an “earth commode”).

By September 25, 1886 the city of Dallas was worried about the quality of its water supply, which came from the Trinity River and from local springs. The Dallas Morning News said Dallas was receiving from Fort Worth river water that was “beyond any possibility of purifaction.”

By September 25, 1886 the city of Dallas was worried about the quality of its water supply, which came from the Trinity River and from local springs. The Dallas Morning News said Dallas was receiving from Fort Worth river water that was “beyond any possibility of purifaction.”

On May 5, 1887 the Fort Worth Gazette responded to a plea by the Dallas Times for pure drinking water. The Gazette hoped that Dallas could find a source of drinking water other than the Trinity River because if cholera broke out because Dallasites drank river water polluted by Fort Worth sewage, “Fort Worth and all Texas would suffer.”

On May 5, 1887 the Fort Worth Gazette responded to a plea by the Dallas Times for pure drinking water. The Gazette hoped that Dallas could find a source of drinking water other than the Trinity River because if cholera broke out because Dallasites drank river water polluted by Fort Worth sewage, “Fort Worth and all Texas would suffer.”

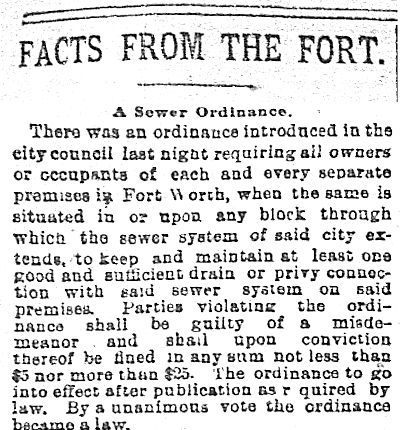

On November 13, 1890 the Dallas Morning News reported that Fort Worth had passed an ordinance requiring owners of houses located on blocks served by a sewer line to maintain a “drain or privy connection” to that line.

On November 13, 1890 the Dallas Morning News reported that Fort Worth had passed an ordinance requiring owners of houses located on blocks served by a sewer line to maintain a “drain or privy connection” to that line.

These classified ads from the August 8, 1901 Fort Worth Register show that water closets, bathrooms, hot water, sewage, and electric lights were something to brag about in the new century.

These classified ads from the August 8, 1901 Fort Worth Register show that water closets, bathrooms, hot water, sewage, and electric lights were something to brag about in the new century.

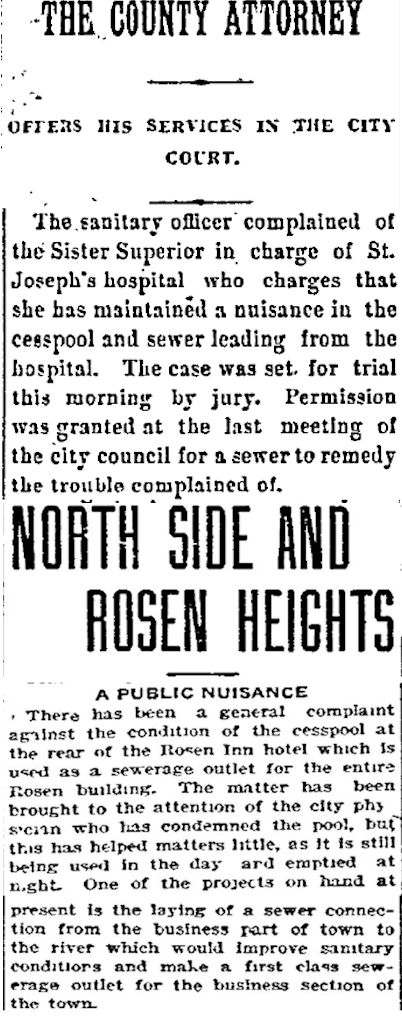

Indeed, as the twentieth century began, many private homes and businesses still had outhouses or cesspools. In 1897 St. Joseph Hospital had a cesspool. In 1904 Sam Rosen’s hotel had a cesspool. Clips are from the July 3, 1897 Register and January 7, 1904 Telegram. Note that the Rosen clip says a sewer line being laid from “the business part of town” (the city of North Fort Worth) to the river would “make a first class sewerage outlet.”

Indeed, as the twentieth century began, many private homes and businesses still had outhouses or cesspools. In 1897 St. Joseph Hospital had a cesspool. In 1904 Sam Rosen’s hotel had a cesspool. Clips are from the July 3, 1897 Register and January 7, 1904 Telegram. Note that the Rosen clip says a sewer line being laid from “the business part of town” (the city of North Fort Worth) to the river would “make a first class sewerage outlet.”

And it was in that city of North Fort Worth in 1903 that a major boon for the greater Fort Worth economy would bring a major increase in the sewage that Cowtown dumped into the Trinity River—sewage that flowed downstream from Cowtown—out of sight and out of mind—and became the problem of someone else.

And that someone else’s name starts with a Big D.

Thanks for this terrific article.

Would you know when Waco put in a sewer or had indoor plumbing? I’m working on something and would love to include the information, but haven’t found it yet.

Thanks, Chris. I can’t answer your question. The Fort Worth newspapers would not have covered Waco that closely, I suspect. But Newspapers.com has the Waco Morning News from 1888 to 1918.

The saying when I was in school*, was “Flush the commode, Dallas needs the water”.

*(Paschal High School, 1957)

More good detective work from Mike. Watch out for those landmines, west Texas. Well, normally I would say something nasty about Funky Town. But this time they were right. And Dallas was correct in being worried. They should still be. Remember Dr. Strangelove. You will never see a Commie drinking tap water. You never see a Mex doing so, either. Note all the special water kiosks around town. They will drink bottled water only.

Thanks, Earl. Dr. Strangelove is one of my favorites. This week I have been watching Sterling Hayden (General Jack D. Ripper) in the film noir classic Asphalt Jungle.

“…there was a toilet behind every tree…”

Must have been tough to live in West Texas!

It was no place for the modest. Where is a tumbleweed when you need one?