To the chagrin of many a student, history loves to hang its hat on dates—on years (1492, 1776), on days (December 7, September 11). But it’s seldom that history can hang its hat on a minute. One such minute was 11:23. In Fort Worth the days leading up to and following 11:23 a.m., July 19, 1876 were spent first in anticipation and then in celebration of the biggest thing to hit Cowtown since the cow: the railroad.

The campaign to bring a railroad to town had actually begun in 1858 when citizens of Fort Worth at a mass meeting, led by E. M. Daggett (left) and J. C. Terrell (right), wrote resolutions urging the Houston & Texas Central railroad to come to town. That didn’t happen. At least not right away.

The campaign to bring a railroad to town had actually begun in 1858 when citizens of Fort Worth at a mass meeting, led by E. M. Daggett (left) and J. C. Terrell (right), wrote resolutions urging the Houston & Texas Central railroad to come to town. That didn’t happen. At least not right away.

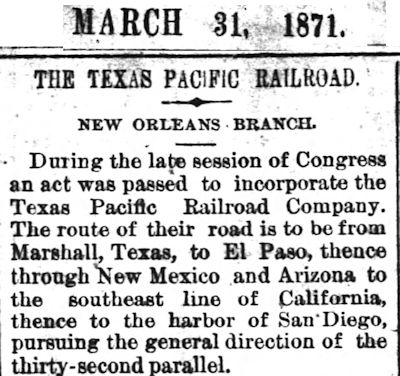

Fast-forward to 1872. Hopes for a railroad for Fort Worth were revived when Colonel Thomas A. Scott, head of Texas & Pacific railroad, assured Fort Worth that the town would be on the T&P route as track was laid westward across Texas from Longview toward the Pacific Ocean.

Fast-forward to 1872. Hopes for a railroad for Fort Worth were revived when Colonel Thomas A. Scott, head of Texas & Pacific railroad, assured Fort Worth that the town would be on the T&P route as track was laid westward across Texas from Longview toward the Pacific Ocean.

The Texas legislature had promised T&P a land grant of sixteen sections (1 section=640 acres) of land per mile if the railroad reached Fort Worth by January 1, 1873.

So eager for its first railroad was Fort Worth that the town sweetened the deal: Major K. M. Van Zandt, E. M. Daggett, Thomas J. Jennings, and H. G. Hendricks donated 320 acres for T&P to locate its passenger depot, roundhouse, and railyard a mile south of the courthouse—with the same January 1, 1873 deadline.

When T&P missed that January 1, 1873 deadline, the legislature extended the deadline. So did Fort Worth.

Missed deadline notwithstanding, the mere promise of a railroad caused a boom in Fort Worth. Fort Worth’s population, the Star-Telegram wrote in 1949, soared from three hundred in 1872 to three thousand in 1873. Fortunes were made in real estate.

B. B. Paddock’s Fort Worth Democrat gleefully ticked off the numbers as the town grew on mere speculation of a railroad: “Two more dry-good stores. Two more drugstores. Two more printing offices. Another livery stable. Three brick kilns in progress.” Soon wholesale grocer Joseph A. Brown came to town. So did lumberman A. J. Roe. And hardware man Charles E. Nash. The bank that would become Fort Worth National was chartered. On March 1, 1873 the city incorporated, elected its first mayor and city council.

Sure enough, by August 1873 the Texas & Pacific railroad had laid tracks westward from Longview to Dallas. Fort Worth was just thirty miles away. Cowtown could almost smell the smoke of the locomotive, could almost hear the shriek of the steam whistle.

In fact, so convinced was Democrat editor (and Cowtown’s head cheerleader) Paddock that Fort Worth was destined to become a railroad hub that in 1873 he drew his tarantula map that showed Fort Worth as a bona-fide railroad hub in the near future.

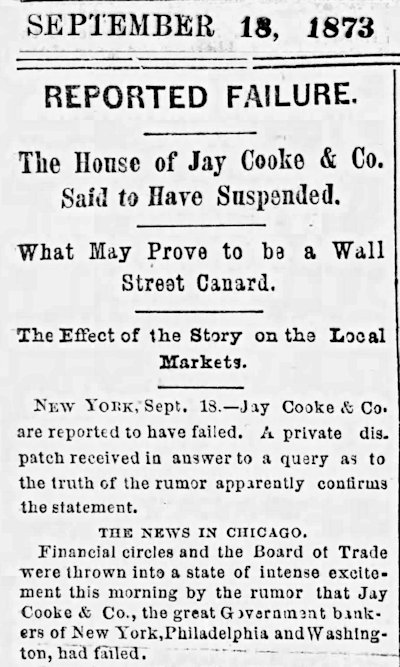

But then came Black Friday. On September 18, 1873 the Wall Street banking firm of Jay Cooke failed, triggering a domino effect of failures that led to an national economic panic. Work on laying the T&P track stalled at Dallas. For Fort Worth the economic panic brought a double whammy: Fort Worth didn’t get the railroad, but downstream arch rival Dallas did. Fort Worth languished. Its population declined. Mayor William Paxton Burts in 1874 said the population was only six hundred. On February 2, 1875 Robert Cowart, a Dallas lawyer who had formerly lived in Fort Worth, wrote a tongue-in-cheek article in the Dallas Daily Herald in which he claimed that Fort Worth had become such a sleepy “suburban village” that one night a panther had come up from the river bottom and wandered the downtown streets “at his own sweet will.”

But then came Black Friday. On September 18, 1873 the Wall Street banking firm of Jay Cooke failed, triggering a domino effect of failures that led to an national economic panic. Work on laying the T&P track stalled at Dallas. For Fort Worth the economic panic brought a double whammy: Fort Worth didn’t get the railroad, but downstream arch rival Dallas did. Fort Worth languished. Its population declined. Mayor William Paxton Burts in 1874 said the population was only six hundred. On February 2, 1875 Robert Cowart, a Dallas lawyer who had formerly lived in Fort Worth, wrote a tongue-in-cheek article in the Dallas Daily Herald in which he claimed that Fort Worth had become such a sleepy “suburban village” that one night a panther had come up from the river bottom and wandered the downtown streets “at his own sweet will.”

And worse, with the national economy depressed until 1879, other existing or proposed railroads that Fort Worth had hoped would come to town—Fort Worth, Cleburne & Waco; Beaumont, Corsicana & Fort Worth; Fort Worth & Denver City; Fort Worth & New Orleans; Houston & Texas Central; Missouri-Kansas-Texas; Red River & Rio Grande—also put plans on hold.

The sympathetic Texas Legislature extended the deadline for T&P to January 1, 1874. But that deadline, too, was missed.

In 1874 the T&P extended the track six miles west to Eagle Ford. Now Fort Worth was just twenty-four miles from its future.

But then a new threat: The delegates to the state Constitutional Convention of 1875 stipulated that T&P would lose its promised land grant if Fort Worth was not reached by the adjournment of the first legislature to meet under the new constitution of 1876.

Faced with this new deadline, Fort Worth took the cowcatcher by the horns. With a “get ’er done” attitude that would serve Fort Worth well in the future, citizens formed the Tarrant County Construction Company, headed by Van Zandt, Jesse Zane-Cetti, John Hirschfield, and W. A. Huffman. The company offered T&P a new deal: We will pay a contractor to grade the roadbed from Eagle Ford to Fort Worth and install bridges and culverts. You lay the tracks and put the rolling stock on those tracks.

Deal.

But work on the roadbed by the local contractor hired by Tarrant County Construction Company progressed slowly. Too slowly for T&P, which did not want to lose that fat land grant. Frustrated, T&P asked the legislature for another deadline extension.

No deal.

The land grant promise would expire when the legislature adjourned.

So, T&P took over the work of the local contractor and began both grading the roadbed and laying the tracks.

After a delay of three years, once again the track was moving toward Fort Worth. But with each clang of hammer on spike, the clock was ticking.

Fast-forward to July 1876. Hopes were high. The long-delayed railroad, Paddock and the Democrat knew, was going to change everything for Fort Worth. The railroad would create jobs, increase the population. (Indeed it did: By 1880 the population would rebound and increase to six thousand.) More hotels, more houses would be needed. More everything would be needed. Fort Worth would be connected to the rest of the country via an iron Internet. Cowtown would get its frontier mojo back! Yee-hah!

As the track inched toward Fort Worth from the east, Paddock and his Democrat had three civic obligations: 1. to report regularly on how far the track had progressed, 2. to pat Fort Worth on its collective back for the tremendous asset it finally was about to acquire (Part 2), and 3. to tweak the collective nose of Dallas (Part 3), which would no longer be the western terminus of the T&P and which, in Fort Worth’s collective mind, had lorded it over the sleepy “suburban village” of “Pantherville” for far too long.

An optimistic T&P, the Star-Telegram wrote in 1949, ordered twenty locomotives and four hundred cars. The Democrat wrote in 1876: “As soon as the track is laid the cars will begin delivering timber and lumber for the most extensive cattle yards in the state.” (And indeed an early map shows a modest stockyards near the T&P depot south of downtown before a stockyards was built north of downtown.)

On July 4, 1876, in a grand gesture that celebrated both America’s independence centennial and Fort Worth’s imminent coming of age, the weekly Democrat became the daily Democrat. Now Paddock and his newspaper could provide readers with daily coverage of the railroad’s progress.

But meanwhile down in Austin, the state legislature had finished its work and wanted to adjourn. The Senate sent the House a resolution to adjourn. T&P was going to lose its land grant. Fort Worth, so close and yet so far, was going to lose its railroad.

Then came an unlikely hero. Tarrant County’s representative in the Texas House was Nicholas Henry Darnell. As the House began to vote to adjourn, Darnell was ill. But each day for fifteen days as the railroad got ever closer to Fort Worth, Darnell was carried into the House chamber on a cot to vote “nay” to adjournment.

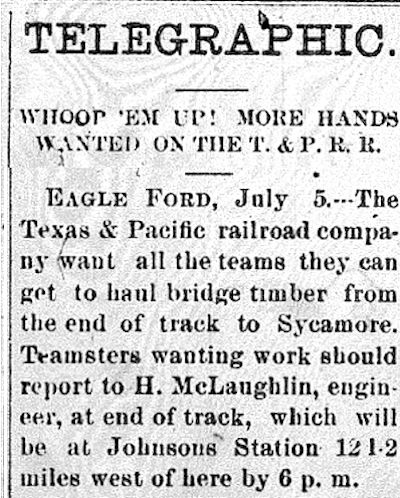

Meanwhile, sweating in the Texas summer heat, workers laid track at a rate of one mile a day. On July 6 the Democrat reported that the T&P supervisors at Eagle Ford were calling for teams to haul bridge timber from the end of the track at Johnson Station (in today’s Arlington) to Sycamore Creek (at the old Sycamore Golf Course). The track had advanced about thirteen miles from Eagle Ford to Johnson Station. That many more miles remained to reach Fort Worth.

Meanwhile, sweating in the Texas summer heat, workers laid track at a rate of one mile a day. On July 6 the Democrat reported that the T&P supervisors at Eagle Ford were calling for teams to haul bridge timber from the end of the track at Johnson Station (in today’s Arlington) to Sycamore Creek (at the old Sycamore Golf Course). The track had advanced about thirteen miles from Eagle Ford to Johnson Station. That many more miles remained to reach Fort Worth.

Cowtown’s future was halfway home.

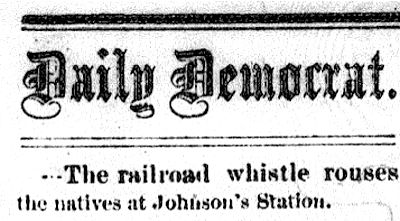

On July 8 the Democrat reported that the sound of a steam locomotive’s whistle was heard at Johnson Station.

On July 8 the Democrat reported that the sound of a steam locomotive’s whistle was heard at Johnson Station.

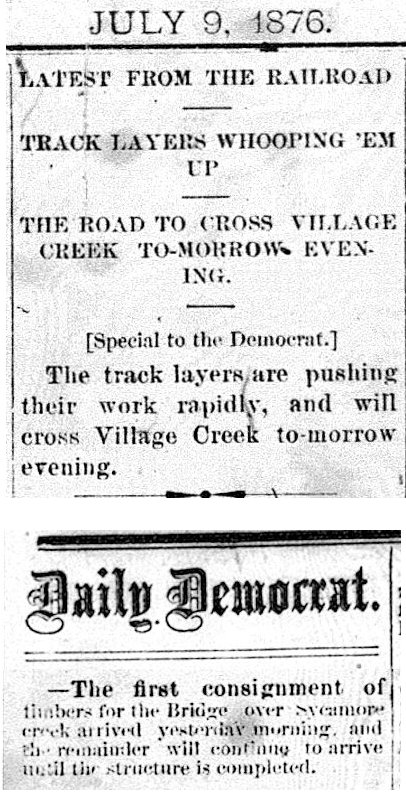

On July 9 the Democrat reported that the track was about to cross Village Creek, putting the track four miles closer to Fort Worth. (In 1885 the T&P would lose a locomotive in Village Creek.) Closer to Cowtown, the first consignment of bridge timbers for Sycamore Creek also had arrived.

On July 9 the Democrat reported that the track was about to cross Village Creek, putting the track four miles closer to Fort Worth. (In 1885 the T&P would lose a locomotive in Village Creek.) Closer to Cowtown, the first consignment of bridge timbers for Sycamore Creek also had arrived.

Building bridges across streams was a major challenge to the track layers. Three streams had to be bridged: the Trinity River at Eagle Ford, Village Creek in Arlington, and Sycamore Creek in what is today east Fort Worth.

Building bridges across streams was a major challenge to the track layers. Three streams had to be bridged: the Trinity River at Eagle Ford, Village Creek in Arlington, and Sycamore Creek in what is today east Fort Worth.

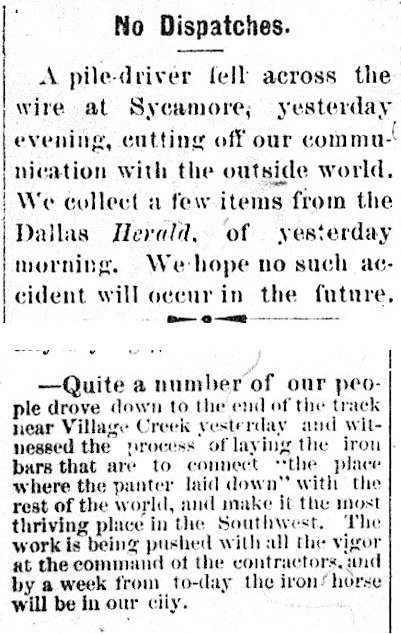

On July 12 the Democrat reported that a pile driver working at Sycamore Creek had cut the telegraph wire between Dallas and Fort Worth, leaving the Democrat largely bereft of outside news.

The newspaper also reported that some Fort Worth residents had driven out to Village Creek to watch the progress as the track crept closer to “the place where the panter laid down.” (The word panther was often spelled panter in the context of Robert Cowart’s yarn.)

On July 14 the Democrat reported that citizens also were driving out to Sycamore Creek every evening to watch the bridge being built. The bridge was the last major challenge for the workers. There was not time to build a proper trestle, so workers hastily threw up a makeshift “crib” to get the first train over the creek and on its way into Fort Worth.

On July 14 the Democrat reported that citizens also were driving out to Sycamore Creek every evening to watch the bridge being built. The bridge was the last major challenge for the workers. There was not time to build a proper trestle, so workers hastily threw up a makeshift “crib” to get the first train over the creek and on its way into Fort Worth.

After building the crib, with little time to grade and level a roadbed, workers laid track on a dirt road. Ties were weighted with stones at each end. Paddock’s Democrat later would write of the track: “It was as crooked as the proverbial ram’s horn, but it bore the rails.”

As Representative Darnell delayed adjournment in Austin, in Fort Worth citizens pitched in: Employers released workers to go work on the railroad; women delivered sandwiches to the rail workers. The rail workers called the women “angels.”

Workers began to work day and night shifts with little sleep in between.

On July 15 the Democrat mitigated the drama with some comic relief: A young horseman was riding out to look at the track-laying progress when he was distracted by a “pretty damsel” and fell flat on his caboose.

On July 15 the Democrat mitigated the drama with some comic relief: A young horseman was riding out to look at the track-laying progress when he was distracted by a “pretty damsel” and fell flat on his caboose.

The July 17 briefs column of the Democrat began appropriately with an ad for men’s briefs but followed with more news of the track-laying. The newspaper office apparently had field glasses that afforded a view of the distant workers. The Democrat reported even being able to see—with unaided eye—the workers at Sycamore Creek three miles away.

The July 17 briefs column of the Democrat began appropriately with an ad for men’s briefs but followed with more news of the track-laying. The newspaper office apparently had field glasses that afforded a view of the distant workers. The Democrat reported even being able to see—with unaided eye—the workers at Sycamore Creek three miles away.

In a clever legal “fudge” the Fort Worth city council extended the city limits a quarter-mile east toward the approaching track.

On July 18 the Democrat broke out the journalistic razzle-dazzle: an engraving. Such illustrations in those days were usually limited to ads. Even though the construction train (which delivered workers and building materials) apparently crossed the new eastern city limits on July 18, that event did not count as the official arrival of the railroad. Nonetheless, the Democrat urged residents to drive out and welcome the workers.

On July 18 the Democrat broke out the journalistic razzle-dazzle: an engraving. Such illustrations in those days were usually limited to ads. Even though the construction train (which delivered workers and building materials) apparently crossed the new eastern city limits on July 18, that event did not count as the official arrival of the railroad. Nonetheless, the Democrat urged residents to drive out and welcome the workers.

In another brief of July 18 the Democrat indicated that the track was now three miles from downtown—at or near Sycamore Creek.

And then suddenly the track was nearing the site where the depot would be built (Main Street at Lancaster Avenue). But a duck pond lay dead ahead. With no time to drain and fill the pond, rail workers curved the track around the pond.

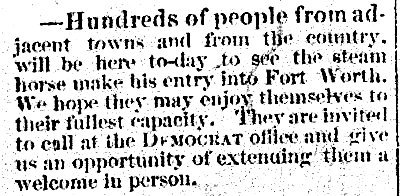

The long-awaited day—July 19—arrived. The morning-edition Democrat predicted that hundreds of people would be in town to watch Fort Worth enter the steam age.

The long-awaited day—July 19—arrived. The morning-edition Democrat predicted that hundreds of people would be in town to watch Fort Worth enter the steam age.

And they did: Thousands of people turned out dressed in their finery to see the “contraption.” The twelve-piece Fort Worth Cornet Band played.

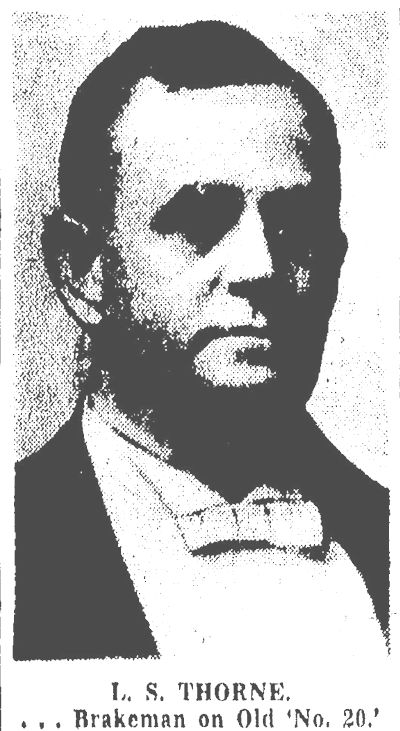

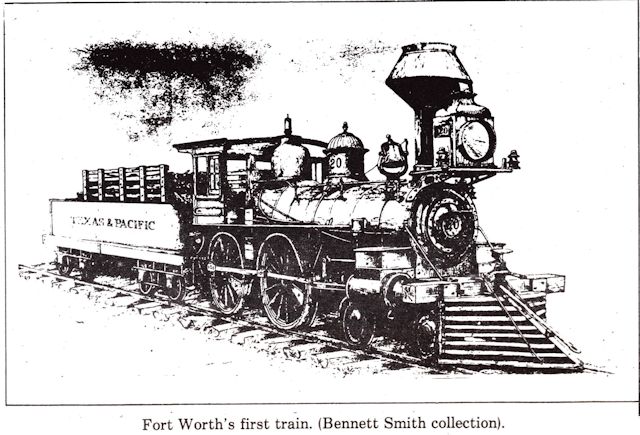

Texas & Pacific construction locomotive No. 20 was hauling four flat cars, three crewmen (engineer James Kelly, conductor W. R. Bell, and brakeman L. S. Thorne), and one town’s future as it puffed and wobbled westward into town on temporary tracks.

Texas & Pacific construction locomotive No. 20 was hauling four flat cars, three crewmen (engineer James Kelly, conductor W. R. Bell, and brakeman L. S. Thorne), and one town’s future as it puffed and wobbled westward into town on temporary tracks.

On July 20 the Democrat again indulged in an engraving as it proclaimed that “at last” “the day has come.” As the “contraption” approached, some onlookers cheered the iron behemoth; others feared that it might explode. Cowboys fired pistols into the air. Frightened horses stampeded. J. J. Jarvis clanged a hammer on an anvil borrowed from a blacksmith.

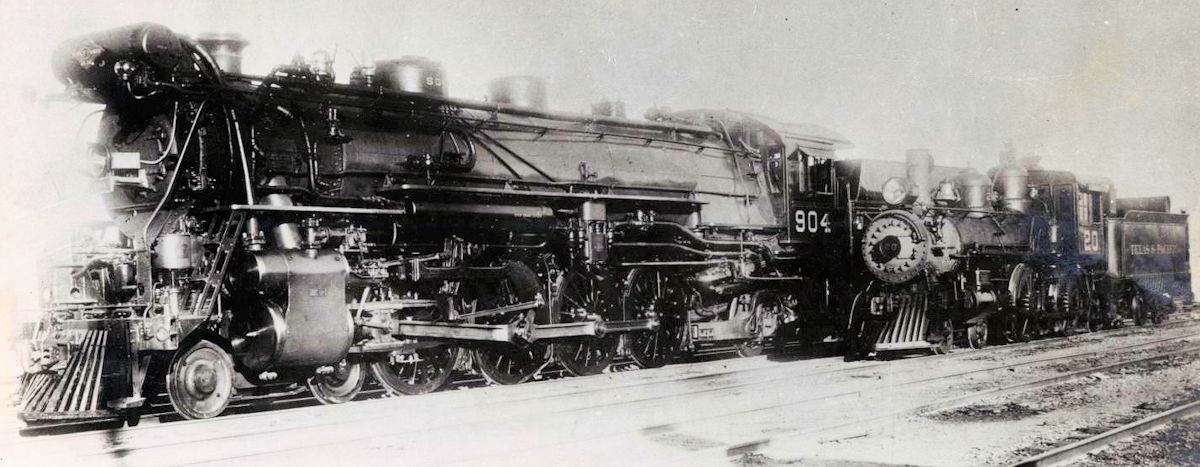

This undated photo shows locomotive No. 20 beside a more modern locomotive. (Photo from Grace Museum.)

This undated photo shows locomotive No. 20 beside a more modern locomotive. (Photo from Grace Museum.)

At last down in Austin, Tarrant County’s Representative Nicholas Henry Darnell could vote “yea” and go home to get well. Because at 11:23 a.m. July 19, 1876 Fort Worth’s future came rolling into town with a shrill scream that aroused the “panter” from his lair.

B. B. Paddock and Pantherville had waited three long years to hear that scream.

11:23 a.m. (Part 2): “A Grand Jollification”

A first-person account of laying the track: Verbatim: Cowpunchers and Cowcatchers

Mr. Nichols,

I read the article Star Telegram abot “The Lake Worth Goatman! It was very interesting and I am old enough to remember all of this when it was going on. I remember all the locations as I grew up in River Oaks and we used to drive around the Lake as teenagers. I had forgotten about Rehab Center but remembered it when you mentioned it in the article. I had never before heard the story about “Foots Fowler” before reading your article. It makes a lot of since and I was wondering where you found this information. thanks for writing the article!

Mr. Gregory, thank you. My sources for most of the blog post and column were the Star-Telegram and Press. Police sergeant Dale Hinz was my sole source for the Foots Fowler theory. He told me that theory in an e-mail before he died. Here is the blog post.

Here’s a photo of T&P locomotive #20 compared to one of the modern steam locomotives T&P operated until steam’s end:

https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth853406/?q=Texas%20%26%20Pacific

Thanks for the tip. I had no idea that a photo of that engine exists.

That had to be a great day for Fort Worth. Where is that “can do” today? It would be neat to find the lost loco. But it was probably recovered. Good story, Mike.

Thanks, Earl. Wish I could have witnessed that day.