He was born more than two centuries ago. In fact, when he was born—1810—older Americans could remember the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Still alive in 1810 were Napoleon, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and England’s King George III. And even though he died seven years before Fort Worth incorporated, he was one of those soldier-statesmen—like Colonel John Peter Smith, Captain Ephraim Merrell Daggett, Major K. M. Van Zandt, Major James Jones Jarvis, and Captain B. B. Paddock—who seemed to leave his fingerprints on every page of early local history. In fact, he is remembered as the father of Tarrant County.

Middleton Tate Johnson was born in South Carolina. By 1832 he was in Alabama, where he was elected to the state legislature at age twenty-two. By 1839 he was in east Texas—Shelby County (Shelby County also sent us Daggett and Captain Charles Turner). When two feuding factions in Shelby County clashed in the Regulator-Moderator War (or Shelby County War) in 1842-1844 over land swindling, fraud, and cattle rustling in east Texas, Johnson was a captain of the Regulators. (Daggett also was a Regulator.)

Middleton Tate Johnson was born in South Carolina. By 1832 he was in Alabama, where he was elected to the state legislature at age twenty-two. By 1839 he was in east Texas—Shelby County (Shelby County also sent us Daggett and Captain Charles Turner). When two feuding factions in Shelby County clashed in the Regulator-Moderator War (or Shelby County War) in 1842-1844 over land swindling, fraud, and cattle rustling in east Texas, Johnson was a captain of the Regulators. (Daggett also was a Regulator.)

During the days of the Republic of Texas Johnson also represented Shelby County in the House and the Senate. After annexation in 1845 he served in the U.S. Army in the Mexican-American War and fought at Monterrey under General William Jenkins Worth. (Photo from Tarrant County College NE.)

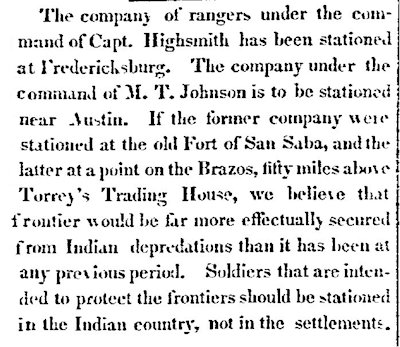

In 1846 Johnson began serving as a Texas Ranger on the northern frontier. The June 7, 1847 Weekly Houston Telegraph offered its opinion on how best to use Johnson’s company to deal with “Indian depredations.”

In 1846 Johnson began serving as a Texas Ranger on the northern frontier. The June 7, 1847 Weekly Houston Telegraph offered its opinion on how best to use Johnson’s company to deal with “Indian depredations.”

Later in 1847 Johnson’s company of Texas Rangers was stationed near a trading post at Marrow Bone Springs (now in Arlington, which was named after Robert E. Lee’s residence). For his service in the Mexican-American War Johnson had received a grant of land at Marrow Bone Springs. He settled his family there in 1848. The settlement that grew up around his home became known as “Johnson Station.” It was located on the only road between Fort Worth and Dallas. A stage coach line served the community.

Later in 1847 Johnson’s company of Texas Rangers was stationed near a trading post at Marrow Bone Springs (now in Arlington, which was named after Robert E. Lee’s residence). For his service in the Mexican-American War Johnson had received a grant of land at Marrow Bone Springs. He settled his family there in 1848. The settlement that grew up around his home became known as “Johnson Station.” It was located on the only road between Fort Worth and Dallas. A stage coach line served the community.

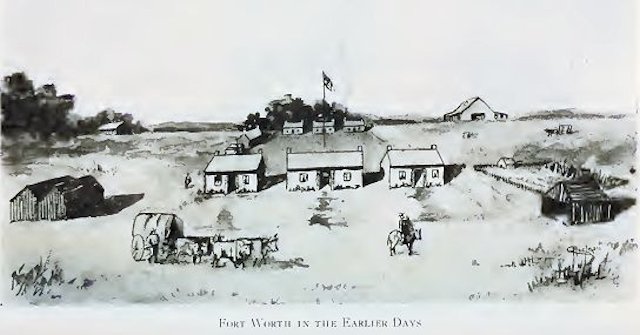

In May 1849 Army Major Ripley Arnold and his dragoons and Colonel Johnson and his Texas Rangers rode west from Johnson Station to scout the location for an Army fort on the Trinity River. On June 6 Arnold established the Army’s Fort Worth. And who owned the land on which the fort was built? Some say that it was owned by Middleton Tate Johnson and Archibald Robinson, who allowed the Army to establish a fort on their land. Johnson also is said by some to have later donated land for the county jail, courthouse, and public square. Other historians dispute the Johnson-Robinson ownership claim and contend that the land was part of Peters Colony. (Drawing from Paddock’s History of Texas.)

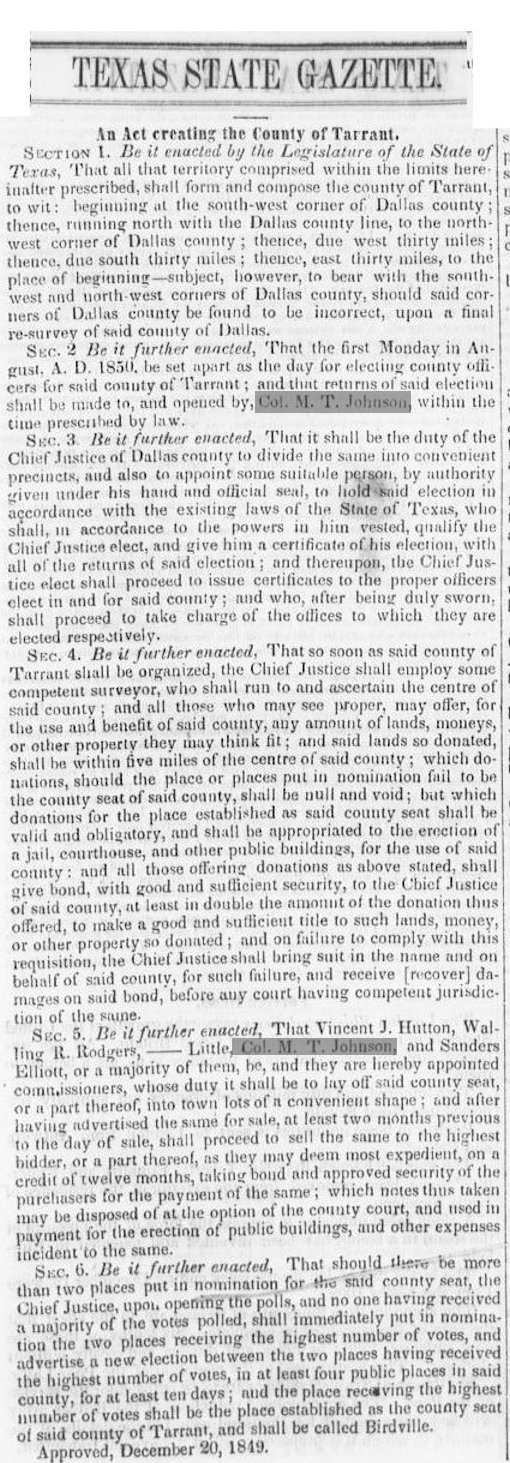

In 1849 the state voted to create a new county from sprawling Navarro County. On February 3, 1850 the Texas State Gazette in Austin, the newspaper of record of state government, published the act creating Tarrant County. I have highlighted where Johnson was mentioned by name as one of the men who would supervise an election of county officers and lay out the county seat.

In 1849 the state voted to create a new county from sprawling Navarro County. On February 3, 1850 the Texas State Gazette in Austin, the newspaper of record of state government, published the act creating Tarrant County. I have highlighted where Johnson was mentioned by name as one of the men who would supervise an election of county officers and lay out the county seat.

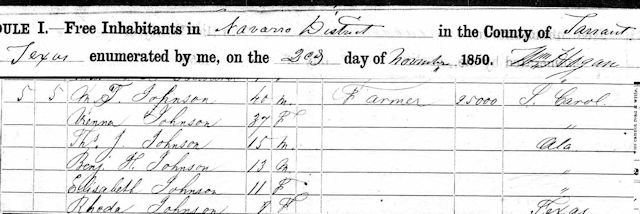

Like so many prosperous men of his time, Middleton Tate Johnson multitasked. He surveyed land, as did John Peter Smith and Albert Gallatin Walker. He established a cotton and corn plantation at Johnson Station and became perhaps the largest slave owner in Tarrant County (see link at bottom). He supplied beef and corn to the Army. He owned a sawmill and a gristmill. He was listed in the 1850 Fort Worth census as a “farmer,” but Johnson became one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in north Texas. (Note that the census calls Navarro a “district.”)

Like so many prosperous men of his time, Middleton Tate Johnson multitasked. He surveyed land, as did John Peter Smith and Albert Gallatin Walker. He established a cotton and corn plantation at Johnson Station and became perhaps the largest slave owner in Tarrant County (see link at bottom). He supplied beef and corn to the Army. He owned a sawmill and a gristmill. He was listed in the 1850 Fort Worth census as a “farmer,” but Johnson became one of the wealthiest and most powerful men in north Texas. (Note that the census calls Navarro a “district.”)

According to the Pioneers Rest Cemetery Association, when Major Arnold’s children Sophie and Willis died in 1850, they were buried on land belonging to Johnson near today’s Samuels Avenue. Fort Worth’s first cemetery grew from those burials. In 1855, when Masons moved the remains of Ripley Arnold (killed in 1853) from Fort Graham to Pioneers Rest in Fort Worth, Johnson led the delegation.

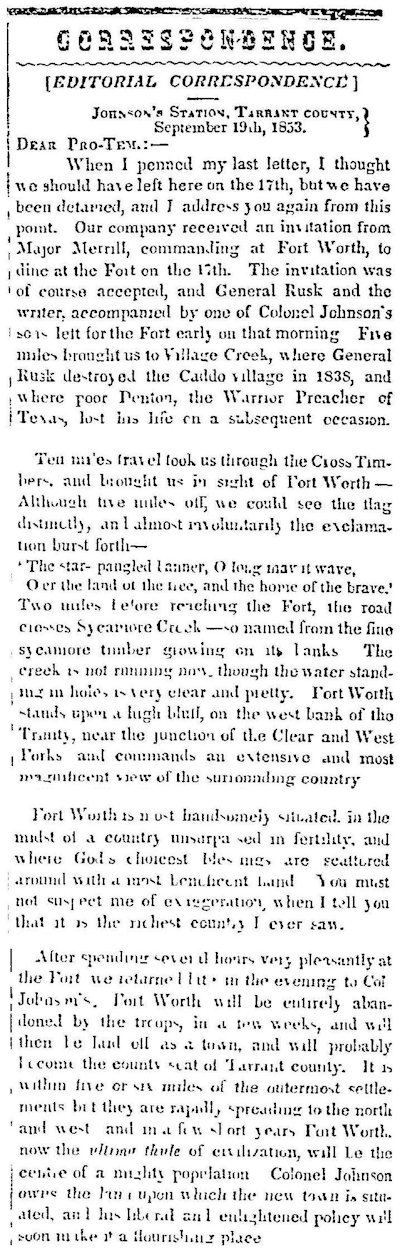

This letter written from Johnson Station in 1853 was published October 4 by the Nacogdoches Chronicle. The writer described a trip to Fort Worth, which the Army was preparing to abandon. The writer mentioned Sycamore Creek and Village Creek, site of General Thomas Jefferson Rusk’s 1838 fight with Native Americans and General Tarrant’s 1841 Battle of Village Creek. The writer also predicted that “Fort Worth, now the ultima thule of civilization, will be the centre of a mighty population” and the county seat. The writer added that Colonel Johnson “owns the land upon which the new town is situated.”

This letter written from Johnson Station in 1853 was published October 4 by the Nacogdoches Chronicle. The writer described a trip to Fort Worth, which the Army was preparing to abandon. The writer mentioned Sycamore Creek and Village Creek, site of General Thomas Jefferson Rusk’s 1838 fight with Native Americans and General Tarrant’s 1841 Battle of Village Creek. The writer also predicted that “Fort Worth, now the ultima thule of civilization, will be the centre of a mighty population” and the county seat. The writer added that Colonel Johnson “owns the land upon which the new town is situated.”

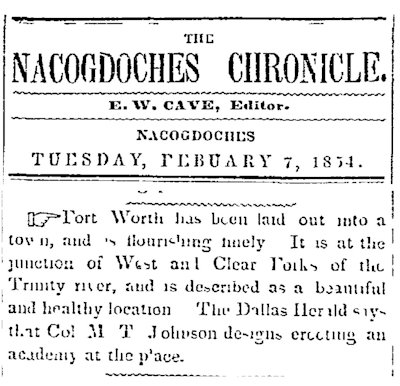

On February 7, 1854 the Nacogdoches Chronicle quoted the Dallas Herald as saying that the new town of Fort Worth had been laid out and was flourishing and that Johnson planned to build an academy.

On February 7, 1854 the Nacogdoches Chronicle quoted the Dallas Herald as saying that the new town of Fort Worth had been laid out and was flourishing and that Johnson planned to build an academy.

Johnson also was a member of Fort Worth’s first Masonic lodge in 1854 and donated land for the lodge building at East Belknap and Grove streets.

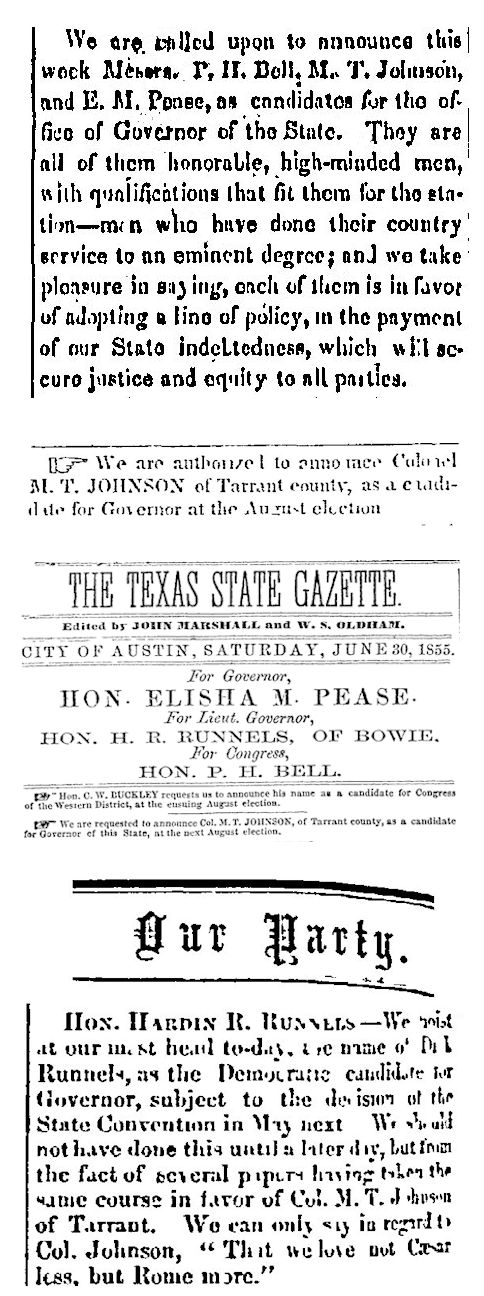

In 1849 Johnson ran for the lieutenant governorship but lost. In 1851, 1853, 1855, and 1857 he ran for governor and lost. Clips, top to bottom, are from the April 10, 1851 Texian Advocate of Victoria, June 7, 1853 Nacogdoches Chronicle, June 30, 1855 Texas State Gazette of Austin, and January 31, 1857 Texas State Gazette. Note that in the 1857 clip the Texas State Gazette favored Hardin Runnels over Johnson for the Democratic nomination. Runnels would indeed win the nomination and defeat Sam Houston. But in 1859 Houston would defeat Runnels after the two men campaigned in Fort Worth. Johnson would host Runnels during his stay here.

In 1849 Johnson ran for the lieutenant governorship but lost. In 1851, 1853, 1855, and 1857 he ran for governor and lost. Clips, top to bottom, are from the April 10, 1851 Texian Advocate of Victoria, June 7, 1853 Nacogdoches Chronicle, June 30, 1855 Texas State Gazette of Austin, and January 31, 1857 Texas State Gazette. Note that in the 1857 clip the Texas State Gazette favored Hardin Runnels over Johnson for the Democratic nomination. Runnels would indeed win the nomination and defeat Sam Houston. But in 1859 Houston would defeat Runnels after the two men campaigned in Fort Worth. Johnson would host Runnels during his stay here.

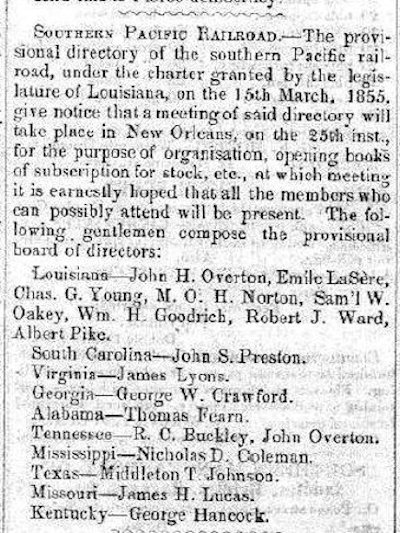

Johnson also was a railroad promoter. He helped General Rusk (for whom our Commerce Street originally was named) survey the proposed Southern Pacific route across Texas to El Paso. The January 2, 1856 South-Western newspaper of Shreveport listed Johnson among the directors of the Southern Pacific.

Johnson also was a railroad promoter. He helped General Rusk (for whom our Commerce Street originally was named) survey the proposed Southern Pacific route across Texas to El Paso. The January 2, 1856 South-Western newspaper of Shreveport listed Johnson among the directors of the Southern Pacific.

Johnson also was instrumental in raising funds in 1859 to build a new Tarrant County courthouse of brick and stone. When Birdville talked the state legislature into reconsidering the election of Fort Worth as county seat, Johnson helped argue Fort Worth’s case.

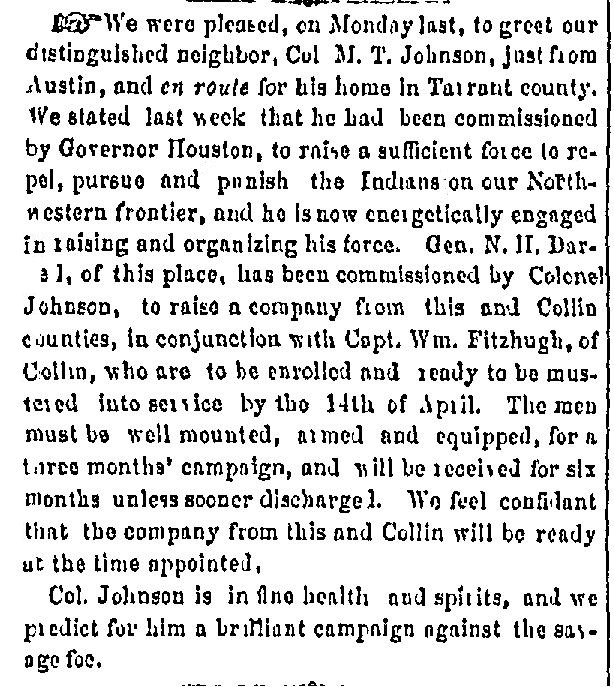

In 1860 Johnson returned to duty as a Texas Ranger. Governor Houston authorized him “to raise a sufficient force to repel, pursue and punish the Indians in our Northwestern frontier.” Clip is from the April 4, 1860 Dallas Weekly Herald.

In 1860 Johnson returned to duty as a Texas Ranger. Governor Houston authorized him “to raise a sufficient force to repel, pursue and punish the Indians in our Northwestern frontier.” Clip is from the April 4, 1860 Dallas Weekly Herald.

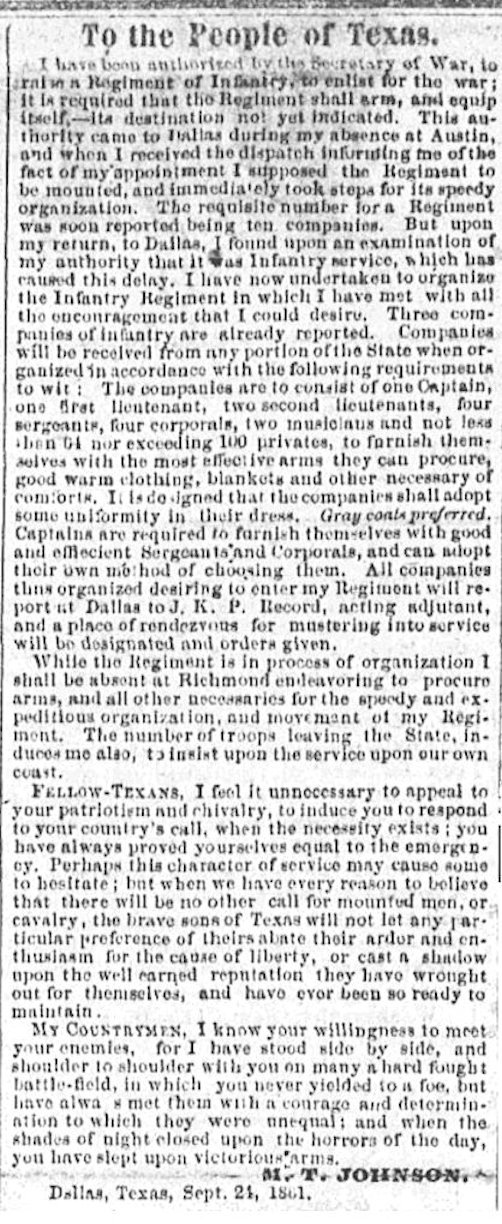

In 1861, although Johnson opposed secession, he raised a cavalry regiment for the Confederacy and served as regimental commander. Volunteers were recruited and drilled at Johnson Station. Jefferson Davis had promised Johnson that if Johnson could raise a brigade, Johnson would be commissioned a brigadier general in the Confederate Army. In this impassioned open letter to Texans in the September 25, 1861 Dallas Weekly Herald Johnson wrote that he had been authorized by the Confederate secretary of war to raise an infantry regiment. Volunteers would supply their own weapons and their own uniforms. “Gray coats preferred.”

In 1861, although Johnson opposed secession, he raised a cavalry regiment for the Confederacy and served as regimental commander. Volunteers were recruited and drilled at Johnson Station. Jefferson Davis had promised Johnson that if Johnson could raise a brigade, Johnson would be commissioned a brigadier general in the Confederate Army. In this impassioned open letter to Texans in the September 25, 1861 Dallas Weekly Herald Johnson wrote that he had been authorized by the Confederate secretary of war to raise an infantry regiment. Volunteers would supply their own weapons and their own uniforms. “Gray coats preferred.”

(Jefferson Davis failed to make Johnson a brigadier general, possibly because Johnson had been so staunchly against secession until Texas seceded.)

According to historian Julia Kathryn Garrett, after Robert E. Lee surrendered in 1865, John Peter Smith and Johnson, dreading life in the South under Reconstruction, fled to Mexico but reconsidered and returned to Tarrant County.

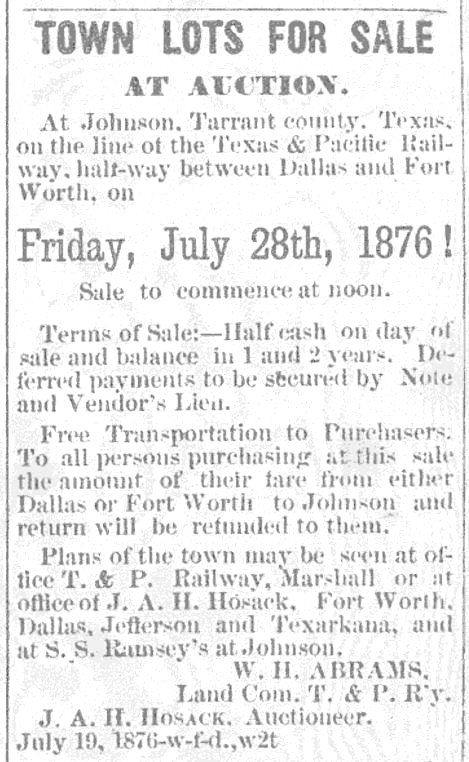

On July 19, 1876—the day the Texas & Pacific railroad reached Fort Worth—B. B. Paddock’s Fort Worth Democrat announced that town lots would go on sale on July 28 in another settlement newly served by the railroad—Johnson Station. (If Arlington’s Abram Street is named for W. H. Abrams, the street signs are shy an s.)

On July 19, 1876—the day the Texas & Pacific railroad reached Fort Worth—B. B. Paddock’s Fort Worth Democrat announced that town lots would go on sale on July 28 in another settlement newly served by the railroad—Johnson Station. (If Arlington’s Abram Street is named for W. H. Abrams, the street signs are shy an s.)

But Middleton Tate Johnson would not live to see those lots sold in the town named for him. After the Civil War Johnson returned to politics. In January 1866 he was elected to the state constitutional convention. But in May (the exact date is disputed) while in Austin he suffered a stroke and died. Clip is from the May 12 Dallas Weekly Herald.

But Middleton Tate Johnson would not live to see those lots sold in the town named for him. After the Civil War Johnson returned to politics. In January 1866 he was elected to the state constitutional convention. But in May (the exact date is disputed) while in Austin he suffered a stroke and died. Clip is from the May 12 Dallas Weekly Herald.

Johnson was honored in various ways. Johnson County was named for him. He originally was buried in the state cemetery in Austin. In 1873 Fort Worth organized a volunteer fire department and named its hook and ladder company for Johnson. (Among the company’s members was Jim Courtright.)

In 1870 Masons of Johnson’s Fort Worth lodge moved his body from the state cemetery. The father of Tarrant County is now buried in the Johnson family cemetery in Arlington where his plantation once stood.

In 1870 Masons of Johnson’s Fort Worth lodge moved his body from the state cemetery. The father of Tarrant County is now buried in the Johnson family cemetery in Arlington where his plantation once stood.

Your historic stories about Fort Worth are wonderful. I never knew I had any connection to Texas and Fort Worth until I took up doing genealogy research. I learned that Capt. Isaac Ferguson was my 4th great grandfather. His daughter Mary Ann Ferguson married Charles Biggers Daggett, brother of Ephraim M. Daggett.

Capt. Isaac Ferguson died January 1848 in Mexico City, leaving widow Elizabeth Johnson Ferguson in Texas. I have a copy of Isaac’s pension file for his service in the Mexican War. One document, filed by widow Elizabeth in Shelby County, Texas in December 1849, was witnessed by E. M. Daggett and M. T. Johnson.

I have never been able to find Elizabeth Johnson’s parents. I am wondering if she might have a family connection to M. T. Johnson. Your history of Johnson has given me some good information - thanks!

Thanks, Marilyn. I was reading the historical marker for Charles Daggett’s crossing just this morning.

Great short biography on MT Johnson, my fifth great

grandfather. I descend through MT and Vienna Johnson’s daughter Louisa who married MJ Brinson.

Thanks, Deborah. He didn’t live to see what a big, BIG figure he would become in local history.

Deborah: I am a commissioner on the Tarrant County Historical Commission and am researching (for a book) on Johnson Station. I would like to speak with descendants of Middleton Tate Johnson. If you have contact information of anyone who might be interested in sharing your family’s history, please leave the name and number for Floreen Henry at the TCHC message bot # 817-212-7462. Thank you, Handlebar!

Deborah, I would be interested in information and photos on M.T.Johnson’s family. I haven’t researched actively for a number of years, but am a descendant through Ben Johnson from Oklahoma.

The previous post was made for me by my husband. If there are direct descendants of Middleton Tate Johnson please post your name and relation.

My wife is the great great great grand daughter of Middleton Tate Johnson (Elizabeth Reid Johnson McLemore)

My husbands 2nd great grandfather. His mother was Margaret McLamore and her mother was Elizabeth Reid Johnson daughter of MT Johnson.

Col. M.T. Johnson was my great-great uncle by marriage.

After reading a hundred or so Texas slave narratives , this one from a stolen soul, Betty Bonner, was a stand out. She was Col. Johnson’s slave. Her story led me to him and this site. He was a compassionate and interesting guy for his peculiar times. I wonder how Betty’s descendants faired? https://www.loc.gov/resource/mesn.161/?sp=115&st=text

Bob, I have written up a half-dozen or so stories of ex-slaves and never been able to find much on their lives beyond the FWP interviews-no obituaries, few census or city directory listings. This is all I have on Betty: Verbatim: “I Hears Marster Say Dem Was de Quantrell Mens” . The ex-slave stories are in Verbatim.

Great history. Arlington knows so little about the community that they swallowed up. In 1857, there was a Comanche attack on Johnson’s Station, if memory serves. Lots of history in this area that most people don’t know about.

Thank you, Jim. Having lived in Arlington for several years, I have tried to include that part of the county with posts on Lake Arlington, Lake Erie, Battle of Village Creek, Randol Mill, Arlington Downs, the lost locomotive, River Legacy Park, etc.

Thank you for all this research…it is so interesting…I have a greater appreciation for M. Johnson’s contribution.

Thanks, Shirley. He was indeed a major figure in our history.

COL Johnson was my Great Great Uncle by marriage.