What he pulled off was a real long shot in his line of work: Whereas gambling led many a man to skid row and a violent death during the nineteenth century, gambling led Jake Johnson to silk stocking row and a natural death.

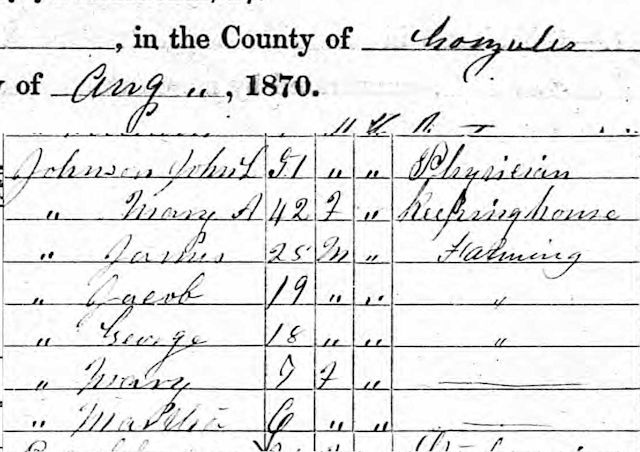

Jacob Christopher Johnson was born in 1850 in Gonzales County. The 1870 census for Gonzales County lists Jake Johnson, age nineteen, as a farmer. His father John was a physician.

Jacob Christopher Johnson was born in 1850 in Gonzales County. The 1870 census for Gonzales County lists Jake Johnson, age nineteen, as a farmer. His father John was a physician.

![]() By 1878 Jake Johnson was in Fort Worth, listed in the city directory as a “drummer” (salesman) for Abe Goldstein’s clothing and furnishings store on Houston Street. But after working hours Johnson was already moving into the realm beyond retail: On September 10, 1878 the Fort Worth Democrat reported that “Jake Johnson was in a fight at the Cattle Exchange [Saloon] late last night and had a large part of his right cheek bitten out by a man named Hardin.”

By 1878 Jake Johnson was in Fort Worth, listed in the city directory as a “drummer” (salesman) for Abe Goldstein’s clothing and furnishings store on Houston Street. But after working hours Johnson was already moving into the realm beyond retail: On September 10, 1878 the Fort Worth Democrat reported that “Jake Johnson was in a fight at the Cattle Exchange [Saloon] late last night and had a large part of his right cheek bitten out by a man named Hardin.”

In 1879 Johnson married Georgia Lebus. They would have six children.

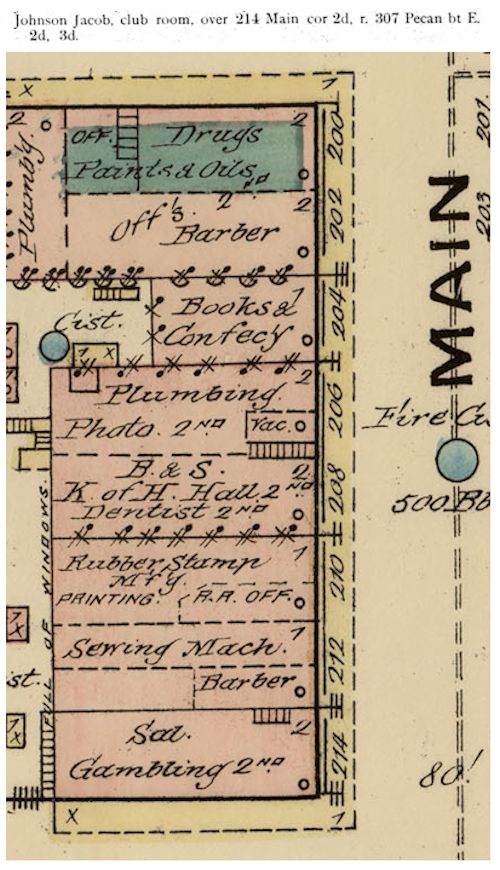

By 1885 Johnson had put down his sales book for good and had picked up deck and dice. The city directory listed Johnson’s place of business as the “club room” over 214 Main Street. A club room was a gambling room, often located over a saloon. Indeed, the 1885 Sanborn map shows a gambling room over the saloon at 214 Main. (There was also a saloon named “Club Room” on Main Street between 1st and 2nd streets.)

By 1885 Johnson had put down his sales book for good and had picked up deck and dice. The city directory listed Johnson’s place of business as the “club room” over 214 Main Street. A club room was a gambling room, often located over a saloon. Indeed, the 1885 Sanborn map shows a gambling room over the saloon at 214 Main. (There was also a saloon named “Club Room” on Main Street between 1st and 2nd streets.)

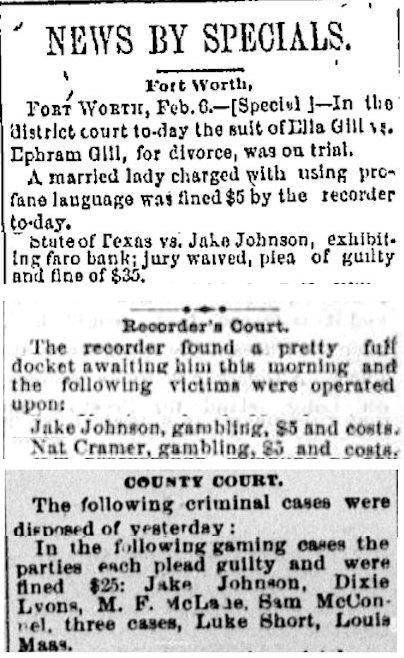

Jake Johnson, Nat Kramer, and Luke Short were Fort Worth’s “three of a kind”: the best-known gamblers in town. They gambled together, owned or operated saloons and club rooms together, showed up in court to pay their fines together.

Jake Johnson, Nat Kramer, and Luke Short were Fort Worth’s “three of a kind”: the best-known gamblers in town. They gambled together, owned or operated saloons and club rooms together, showed up in court to pay their fines together.

Johnson was often in court for gambling, fighting, selling liquor on Sundays in his saloons. Like Short and Kramer he would pay his gambling fine and go right back to the table or the track. (The “M. F. McLane” in the bottom clip probably was Frank McLain, who in 1883 was a member, along with Luke Short, Bat Masterson, and Wyatt Earp, of the “Dodge City Peace Commission.”) Clips are from the February 8, 1883 Dallas Weekly Herald and April 23, 1883 and May 9, 1885 Fort Worth Gazette.

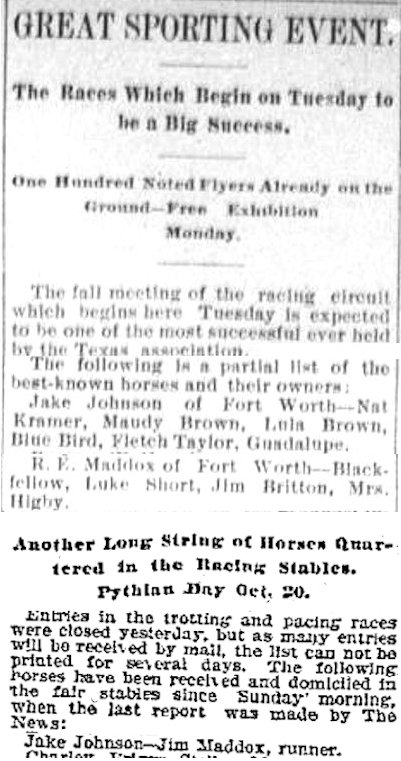

The sporting fraternity in Fort Worth was close. Jake Johnson owned a racehorse named “Nat Kramer” and a racehorse named “Jim Maddox.” Jim Maddox was city marshal in the 1890s and brother of horse breeder Robert E. Maddox, who owned a racehorse named “Luke Short.” Thus, a day at the races with Johnson, Kramer, and Maddox could easily turn into an Abbott and Costello “who’s on first?” routine. Clips are from the November 1, 1885 Fort Worth Gazette and October 7, 1896 Dallas Morning News.

The sporting fraternity in Fort Worth was close. Jake Johnson owned a racehorse named “Nat Kramer” and a racehorse named “Jim Maddox.” Jim Maddox was city marshal in the 1890s and brother of horse breeder Robert E. Maddox, who owned a racehorse named “Luke Short.” Thus, a day at the races with Johnson, Kramer, and Maddox could easily turn into an Abbott and Costello “who’s on first?” routine. Clips are from the November 1, 1885 Fort Worth Gazette and October 7, 1896 Dallas Morning News.

Sometimes a day at the races went sour. On November 8, 1891 the Dallas Morning News reported that Johnson and another local “sporting man” had mutually raised cane.

Sometimes a day at the races went sour. On November 8, 1891 the Dallas Morning News reported that Johnson and another local “sporting man” had mutually raised cane.

Not surprisingly, Johnson, along with A. J. Roe, was a partner in the driving park, which was an early race track off Samuels Avenue. Clip is from the April 14, 1885 Fort Worth Gazette.

Not surprisingly, Johnson, along with A. J. Roe, was a partner in the driving park, which was an early race track off Samuels Avenue. Clip is from the April 14, 1885 Fort Worth Gazette.

Johnson also was an officer of the newly formed gun club. Other officers included former Mayor G. H. Day, Jim Courtright, and A. J. Anderson. Clip is from the December 10, 1883 Fort Worth Gazette.

Johnson also was an officer of the newly formed gun club. Other officers included former Mayor G. H. Day, Jim Courtright, and A. J. Anderson. Clip is from the December 10, 1883 Fort Worth Gazette.

In 1904 Johnson threatened to go to court to close all the pool rooms in Texas because the National News Company was supplying race odds and results to pool rooms but not to him. Clip is from the November 8 Telegram.

In 1904 Johnson threatened to go to court to close all the pool rooms in Texas because the National News Company was supplying race odds and results to pool rooms but not to him. Clip is from the November 8 Telegram.

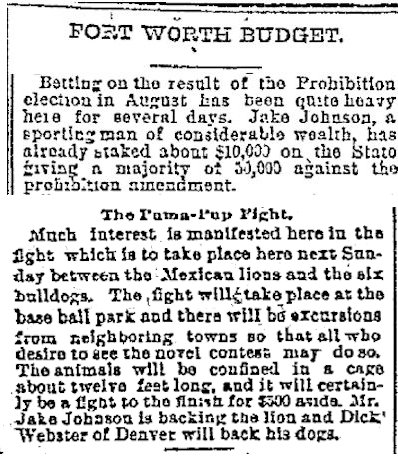

Johnson bet not just on horses and club room games of chance. He also bet on the results of a prohibition election and a fight between caged “Mexican lions” and bulldogs. Clips are from the July 5, 1887 and June 13, 1890 Dallas Morning News.

Johnson bet not just on horses and club room games of chance. He also bet on the results of a prohibition election and a fight between caged “Mexican lions” and bulldogs. Clips are from the July 5, 1887 and June 13, 1890 Dallas Morning News.

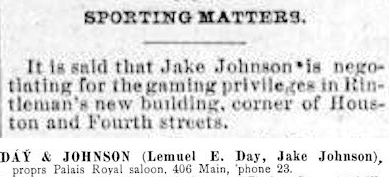

Johnson, like Short and Kramer, branched out from gambling in saloons and club rooms to owning the saloons and club rooms. The 1892 city directory shows that Johnson was partner with Lemuel Day in the Palais Royal Saloon. (Luke Short worked at the Palais Royal after cutting his ties to the White Elephant.) On February 28, 1883 the Fort Worth Democrat reported that Johnson was interested in the gambling concession at Rintleman’s new saloon. Christopher and Gus Rintleman were prominent saloon owners.

Johnson, like Short and Kramer, branched out from gambling in saloons and club rooms to owning the saloons and club rooms. The 1892 city directory shows that Johnson was partner with Lemuel Day in the Palais Royal Saloon. (Luke Short worked at the Palais Royal after cutting his ties to the White Elephant.) On February 28, 1883 the Fort Worth Democrat reported that Johnson was interested in the gambling concession at Rintleman’s new saloon. Christopher and Gus Rintleman were prominent saloon owners.

Johnson and Kramer in the early 1880s also were co-owners of the Cattle Exchange Saloon’s club room. (When Hell’s Half Acre madam Mary Porter died, she left most of her estate to Kramer.)

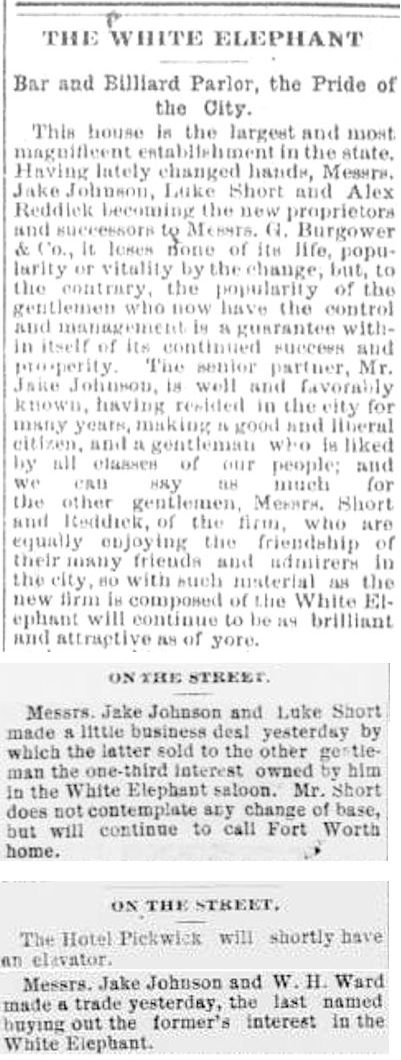

In 1884 Jake Johnson and Luke Short, along with Alex Reddick, bought the White Elephant Saloon from Burgower, Berliner, Bornstein. On February 7, 1887, one day before Short killed Courtright, Short sold his third of the saloon to Johnson. Nine days later Johnson “flipped” his share of the saloon to William Ward. Clips are from the December 21, 1884 and February 8 and February 17, 1887 Fort Worth Gazette.

In 1884 Jake Johnson and Luke Short, along with Alex Reddick, bought the White Elephant Saloon from Burgower, Berliner, Bornstein. On February 7, 1887, one day before Short killed Courtright, Short sold his third of the saloon to Johnson. Nine days later Johnson “flipped” his share of the saloon to William Ward. Clips are from the December 21, 1884 and February 8 and February 17, 1887 Fort Worth Gazette.

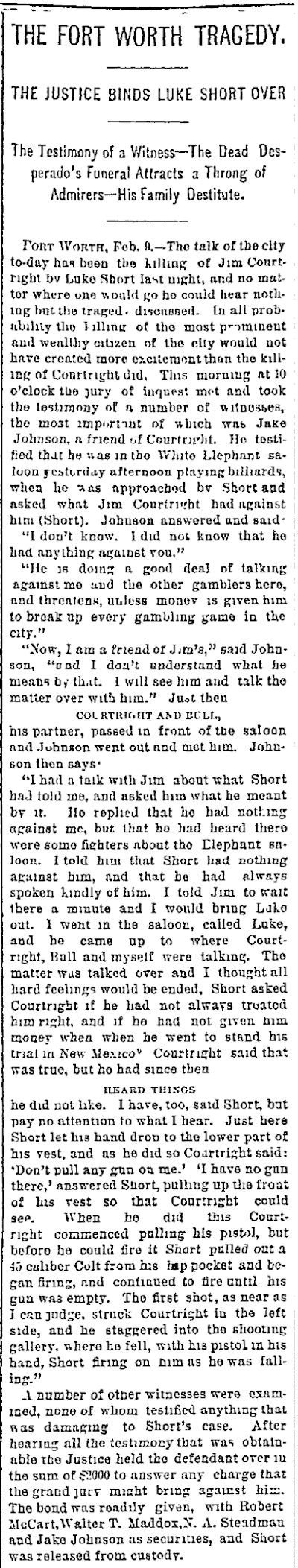

Then came February 8, 1887. Johnson, who was a friend of both Luke Short and Jim Courtright, was the only witness to the Short-Courtright shooting. On February 10 the Dallas Morning News printed his testimony.

Then came February 8, 1887. Johnson, who was a friend of both Luke Short and Jim Courtright, was the only witness to the Short-Courtright shooting. On February 10 the Dallas Morning News printed his testimony.

Note that Johnson put up bail for Short. As did attorney Robert McCart and former Sheriff Walter T. Maddox. Walter Maddox was the brother of horse breeder Robert E. Maddox and Jim Maddox (Jim Maddox the man, not Jim Maddox the racehorse).

One historian speculated that the normally lightning-fast Courtright was slow on the draw that day outside the White Elephant because the hammer of his pistol snagged on his watch chain as he drew. Was that watch chain attached to the watch that Jake Johnson had given to Courtright three years earlier? Clip is from the January 27, 1884 Fort Worth Gazette.

One historian speculated that the normally lightning-fast Courtright was slow on the draw that day outside the White Elephant because the hammer of his pistol snagged on his watch chain as he drew. Was that watch chain attached to the watch that Jake Johnson had given to Courtright three years earlier? Clip is from the January 27, 1884 Fort Worth Gazette.

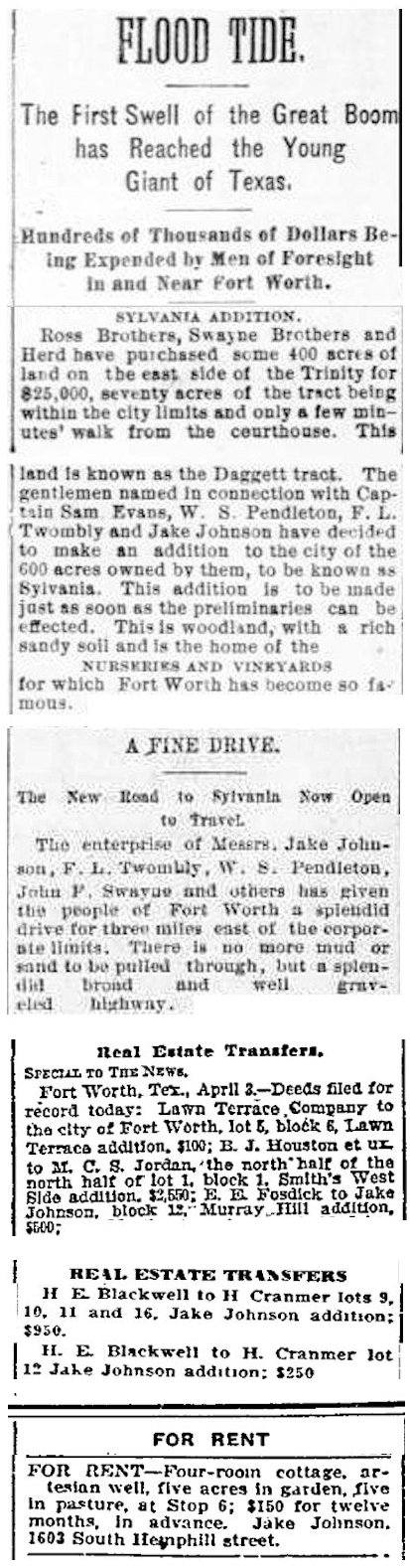

Johnson used his gambling profits to make money away from the race track and the club room. He dealt in cattle. He bought and sold real estate. There is a Jake Johnson Addition in Fairmount. He was one of the developers of the Sylvania subdivision east of the river. Clips are from the October 28 and March 25, 1887 Fort Worth Gazette, February 24, 1889 Fort Worth Gazette, April 4, 1902 Dallas Morning News, May 7, 1903 Fort Worth Telegram, and January 20, 1907 Fort Worth Telegram.

Johnson used his gambling profits to make money away from the race track and the club room. He dealt in cattle. He bought and sold real estate. There is a Jake Johnson Addition in Fairmount. He was one of the developers of the Sylvania subdivision east of the river. Clips are from the October 28 and March 25, 1887 Fort Worth Gazette, February 24, 1889 Fort Worth Gazette, April 4, 1902 Dallas Morning News, May 7, 1903 Fort Worth Telegram, and January 20, 1907 Fort Worth Telegram.

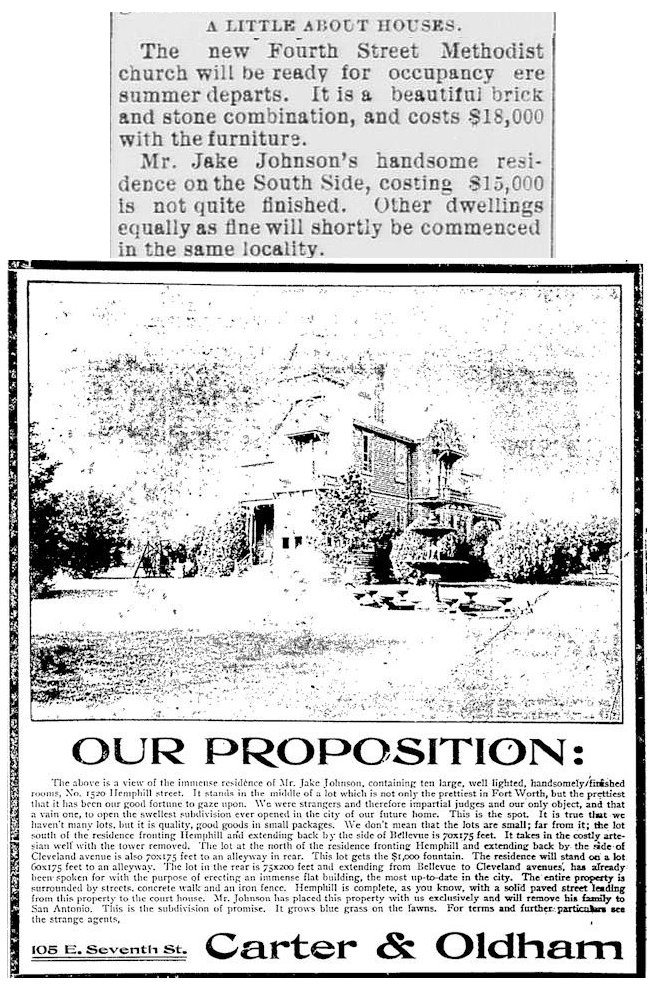

By 1887 Johnson had raked in enough money to build a fine house on Hemphill Street. Just two blocks south on Hemphill Street fellow capitalist E. E. Chase built Bellevue, his “immense residence.” Note that at $15,000 ($383,000 today) Johnson’s house cost only slightly less than the new Methodist church.

By 1887 Johnson had raked in enough money to build a fine house on Hemphill Street. Just two blocks south on Hemphill Street fellow capitalist E. E. Chase built Bellevue, his “immense residence.” Note that at $15,000 ($383,000 today) Johnson’s house cost only slightly less than the new Methodist church.

But by 1909 Johnson was ill, and his “immense residence” in “the swellest subdivision ever opened in this city” was for sale. Clips are from the June 9, 1887 Fort Worth Gazette and January 29, 1909 Star-Telegram.

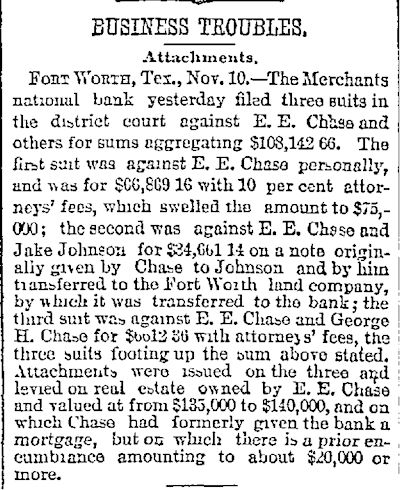

Fellow capitalists and neighbors E. E. Chase and Johnson occasionally did business together. Clip is from the November 11, 1891 Dallas Morning News.

Fellow capitalists and neighbors E. E. Chase and Johnson occasionally did business together. Clip is from the November 11, 1891 Dallas Morning News.

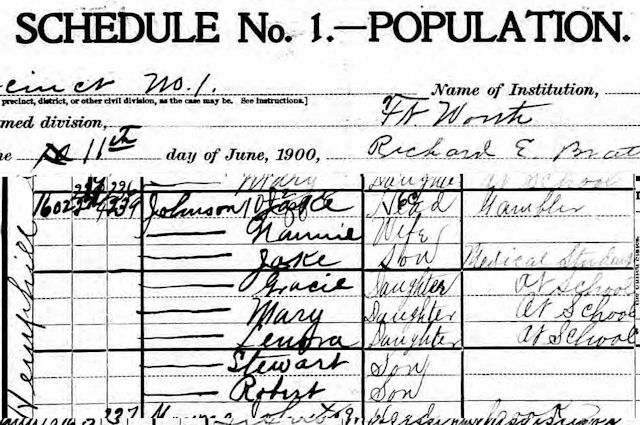

In the 1900 census Jake Johnson listed his “occupation, trade, or profession” as “gambler.” Son Jake Jr. was a medical student.

In the 1900 census Jake Johnson listed his “occupation, trade, or profession” as “gambler.” Son Jake Jr. was a medical student.

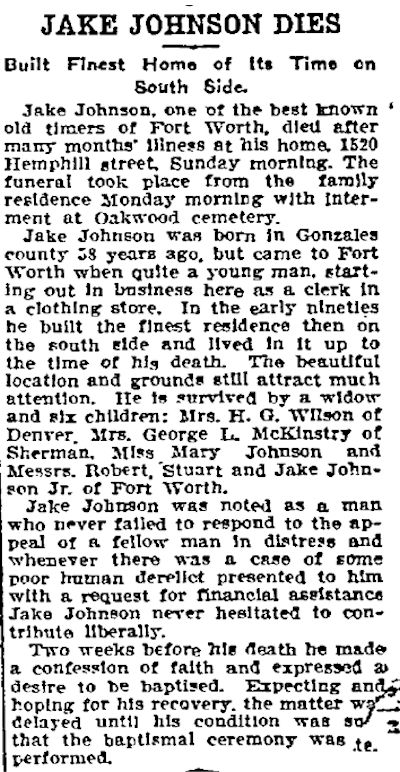

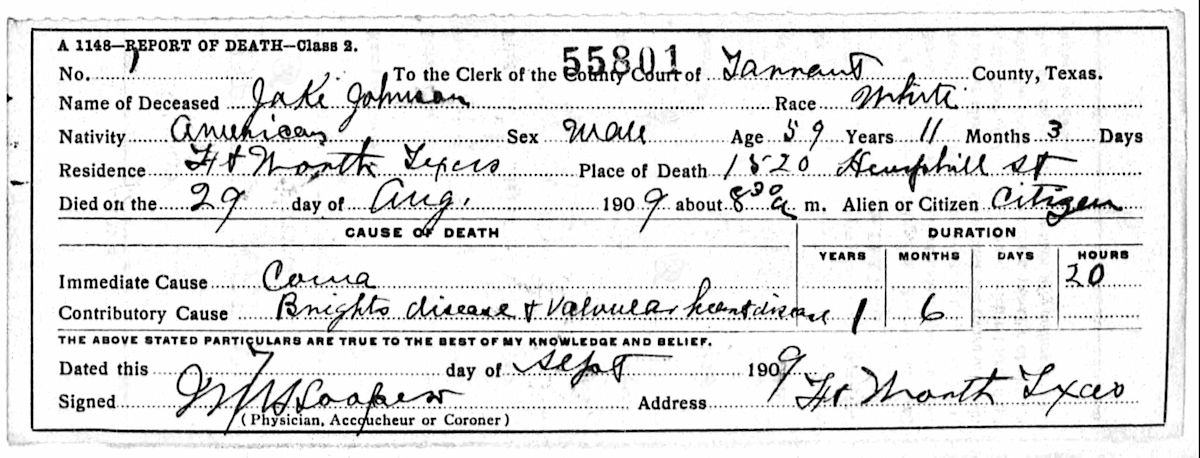

On August 29, 1909 Jake Johnson the gambler folded. Jacob Christopher Johnson died in his “immense residence” on Hemphill Street’s silk stocking row. He was just a month shy of sixty years old. (Luke Short had died at age thirty-nine; Jim Courtright at forty-two.) The Star-Telegram obituary seemed to be in denial of Jake Johnson’s colorful life. His estate was valued at $37,000 ($940,000 today). Clip is from the August 30, 1909 Star-Telegram.

On August 29, 1909 Jake Johnson the gambler folded. Jacob Christopher Johnson died in his “immense residence” on Hemphill Street’s silk stocking row. He was just a month shy of sixty years old. (Luke Short had died at age thirty-nine; Jim Courtright at forty-two.) The Star-Telegram obituary seemed to be in denial of Jake Johnson’s colorful life. His estate was valued at $37,000 ($940,000 today). Clip is from the August 30, 1909 Star-Telegram.

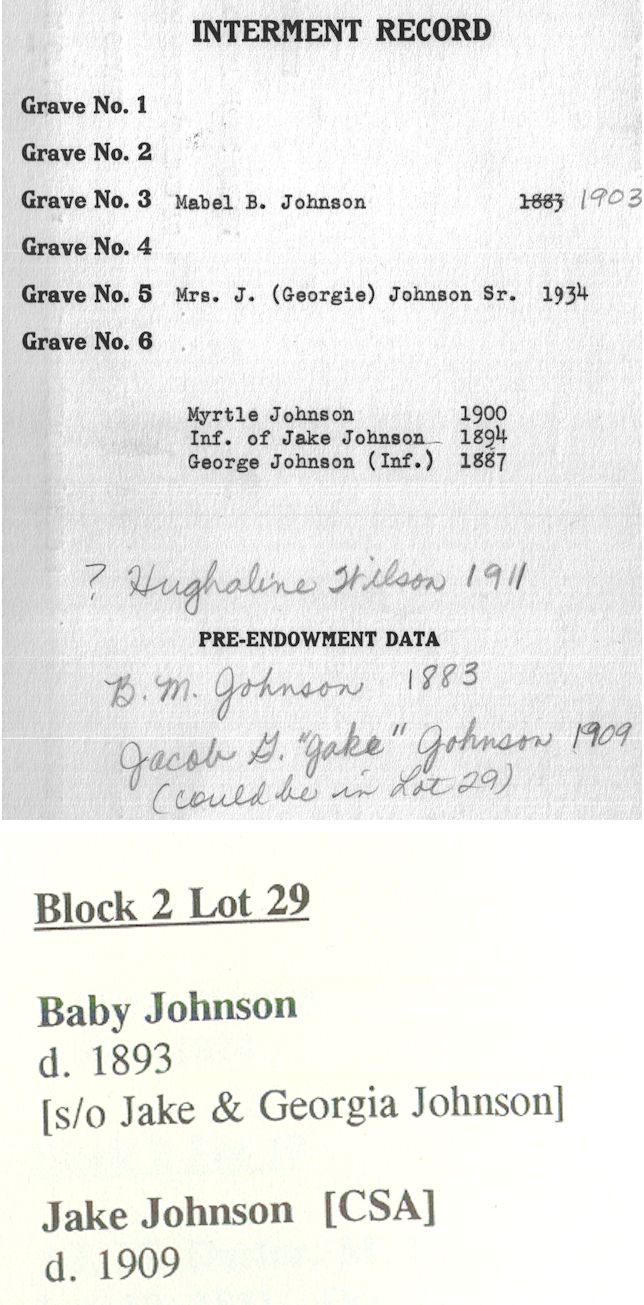

Win, place, and no show: The obituary says Johnson was buried in Oakwood Cemetery. And indeed the records of Oakwood Cemetery (top) indicate that a Jake Johnson who was married to “Georgie” Johnson and who died in 1909 was buried there (no headstone), although the exact location is unclear. (Mrs. Georgia Johnson, per the Oakwood record, indeed died in 1934.) Ah, but the records of Pioneers Rest Cemetery (bottom) indicate that a Jake Johnson who was married to Georgia Johnson and who died in 1909 was buried there (no headstone). A canvass of city directories of the time show only one Jake Johnson in Fort Worth. (Cemetery records from Sarah Biles at Oakwood and the book Pioneers Rest Cemetery.)

Win, place, and no show: The obituary says Johnson was buried in Oakwood Cemetery. And indeed the records of Oakwood Cemetery (top) indicate that a Jake Johnson who was married to “Georgie” Johnson and who died in 1909 was buried there (no headstone), although the exact location is unclear. (Mrs. Georgia Johnson, per the Oakwood record, indeed died in 1934.) Ah, but the records of Pioneers Rest Cemetery (bottom) indicate that a Jake Johnson who was married to Georgia Johnson and who died in 1909 was buried there (no headstone). A canvass of city directories of the time show only one Jake Johnson in Fort Worth. (Cemetery records from Sarah Biles at Oakwood and the book Pioneers Rest Cemetery.)

Buried in two cemeteries? Perhaps the old gambler was just hedging his bets.