Happy birthday to us! Today—June 6—Fort Worth takes a deep breath and blows out the candles on its birthday cake—all 173 of them. On this date in 1849 Major Ripley Allen Arnold raised Old Glory over a new Army outpost on the north Texas frontier and established the fort that this city would grow from.

So, this morning, before the dawn’s early light, I made a pilgrimage to Pioneers Rest Cemetery to commune with the spirit of Rip. . . .

Major Ripley Allen Arnold’s grave is covered by a huge rock and located near the southeast corner of the cemetery.

Major Ripley Allen Arnold’s grave is covered by a huge rock and located near the southeast corner of the cemetery.

To conjure the old soldier, I stand beside the rock and whistle a few bars of “Reveille.” Suddenly a wisp of fog rises from the rock. As I stare, the fog grows more substantial and begins to take form—a human form. Form becomes flesh. Suddenly there atop the rock stands Major Arnold himself. He stands rigidly at attention, the tip of his right forefinger touching the visor of his plumed cocked hat in a well-practiced salute. He is wearing a double-breasted blue frock coat, blue trousers, and an orange sash. His black boots are polished. From his left hip hangs a sword in a scabbard.

“Good morning, Major. And congratulations. This is your big day. In fact, this is a big day for all of us in Fort Worth.”

[Bewildered and blinking, looking down at me, then around at his surroundings, then back at me.] “‘Big day’? ‘Congratulations’? Who in the blue blazes are you?”

“I am a resident of Fort Worth.”

“Balderdash. You’re no soldier of the fort I commanded.”

“No, sir, not that Fort Worth. The Fort Worth you established for the Army was abandoned on September 17, 1853. Today, Major, Fort Worth is a city.”

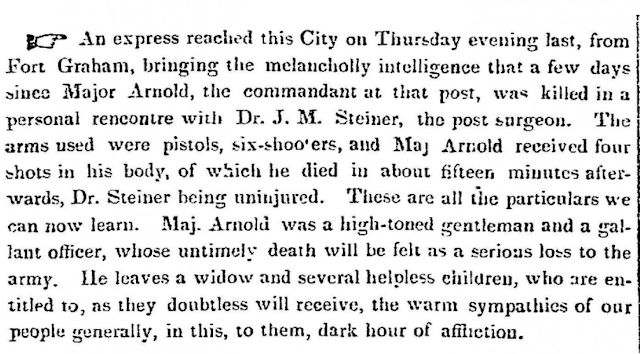

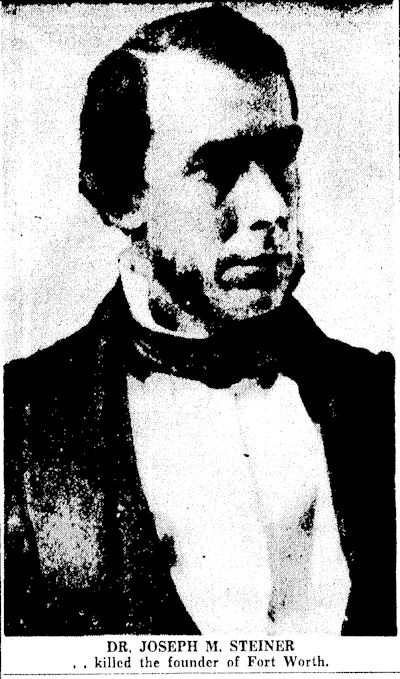

[Looks around at the other tombstones and then down at the “1817-1853” engraved on the huge rock that covers his grave. And he remembers.] “Ah. It’s coming back to me now. [He stares intently.] The last thing I remember, it was that very year: 1853, Fort Graham. Dr. Joseph Murray Steiner, the fort physician—and a thorough blackguard, I hasten to add—was pointing his Colt at me. And the oath that doctor swore was most un-Hippocratic. He fired, and . . .”

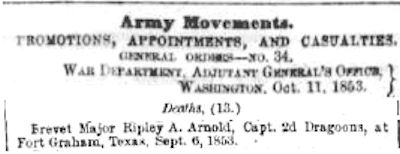

“You were hit four times, Major. The Texas State Gazette on September 10, 1853 reported your death.”

“You were hit four times, Major. The Texas State Gazette on September 10, 1853 reported your death.”

[Processing this 168-year-old news.] “So . . . I am dead. Dead. I had feared as much. [Fatalistic.] Well, so be it. For the soldier death is a way of life. [Looks at me, puzzled. ] But you say I am in Fort Worth, now a city. Why am I not buried at Fort Graham, where I died?”

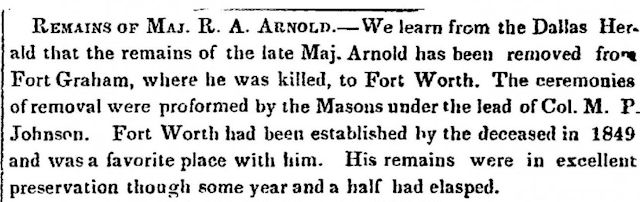

“You were, Major. But in 1855, as the Texas State Gazette reported on June 30, you were moved here to Fort Worth. Your fellow Masons Middleton Tate Johnson and Adolph Gounah were among the men who had your body moved and reburied next to your two children. Remember: Dr. Gounah had Sophie and Willis buried here in 1850.”

“You were, Major. But in 1855, as the Texas State Gazette reported on June 30, you were moved here to Fort Worth. Your fellow Masons Middleton Tate Johnson and Adolph Gounah were among the men who had your body moved and reburied next to your two children. Remember: Dr. Gounah had Sophie and Willis buried here in 1850.”

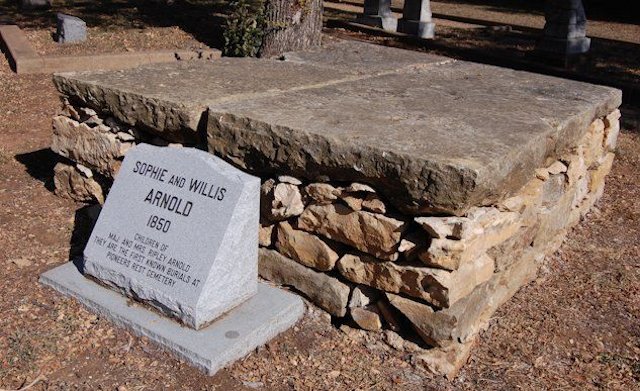

“There they are over there, Major, right beside your grave.”

“There they are over there, Major, right beside your grave.”

[Stares at a nearby stone slab covering a double grave.] “Little Sophie, little Willis! My babies. [Chin trembles briefly, but then soldierly bearing prevails.] Now I remember. We lost them both to cholera.”

[Looks down between his feet.] “What is the reason for this huge rock atop my grave? I’ve been staring up at its underside for a good many years now.”

“This rock is a fairly recent improvement, Major. Your original grave covering had fallen into disrepair some years ago. So, this chiseled rock was installed. See the plaque inset in the rock? That depicts you and your troops. This cemetery, as you may recall, is about half a mile from where you and your troops camped at Live Oak Point while building the fort on the bluff in 1849. This cemetery is also about a half a mile from where you built the fort on the bluff 173 years ago.”

“This rock is a fairly recent improvement, Major. Your original grave covering had fallen into disrepair some years ago. So, this chiseled rock was installed. See the plaque inset in the rock? That depicts you and your troops. This cemetery, as you may recall, is about half a mile from where you and your troops camped at Live Oak Point while building the fort on the bluff in 1849. This cemetery is also about a half a mile from where you built the fort on the bluff 173 years ago.”

[Repeating.] “‘One hundred and seventy-three’ . . .” [With a clatter of the sword on his hip, Arnold sits down on the rock, places a hand on the rock at each side to steady himself.]

“Yes, Major. This is the twenty-first century. It’s 2021. But I must say you look good for a man of two hundred and four.”

[Repeats in awe.] “‘Two thousand twenty’ . . . [Holds out his hands, first palms down and then palms up, and looks at them.] Two hundred and four years old.”

[Hastening to brighten the tone of the conversation.] “Major, do you remember this?”

[Singing.]

“‘Come fill your glasses, fellows, and stand up in a row

[A broad smile of recognition spreads across Rip’s face. He begins to wag his head in time.]

“To singing sentimentally we’re going for to go;

[Rip, haltingly at first, then with confidence, begins to sing along.]

“In the Army there’s sobriety, promotion’s very slow.

“So we’ll sing our reminiscences of Benny Havens, oh!”

[By the chorus Rip is in full voice.]

“Oh! Benny Havens, oh! Oh! Benny Havens, oh!

“We’ll sing our reminiscences of Benny Havens, oh!’”

[Laughing and slapping his knee so hard that his sword rattles.] “By the saints, sir! How that takes me back. Benny Havens! Bless his soul and his bottomless keg!”

“You do remember, Major! As you recall, Benny Havens operated an off-limits tavern that was popular with West Point cadets, yourself included.”

[Chuckling.] “Many a cadet’s legs carried him from his barracks to Benny Havens more steadily than they carried him back to his barracks. Ahem, as you say, myself included.”

“Not to mention, Major, Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, and Jefferson Davis. They all went to Benny Havens as West Point cadets. In 1838 your friend Lieutenant Lucius O’Brien of the 8th Infantry stopped at West Point to visit you on his way to join his regiment. Remember? You took him to Benny Havens, and he liked it so much that he, along with you and two other cadets, wrote the song ‘Benny Havens, Oh.’”

[Self-deprecatingly.] “Oh, it was Lucius’s song, although in those days I did enjoy tinkering with a tune. I may have helped a little.”

“Major, the cadets at West Point still sing your song. There are considerably more stanzas now than when you and Lieutenant O’Brien let the ink dry on the first five.”

“Major, the cadets at West Point still sing your song. There are considerably more stanzas now than when you and Lieutenant O’Brien let the ink dry on the first five.”

[Somber, remembering.] “Lucius was killed in 1841 during the Seminole War in Florida.”

“West Point cadets added a stanza to your song to honor O’Brien:

“‘From the land of death and danger—

“From Tampa’s deadly shore,

“Comes up the wail of manly grief,

“O’Brien is no more.’”

[Swallows hard but then shakes off the grief.] “Rest in peace, sweet Lucius.”

“That year, 1838, you graduated from West Point.”

[Chuckling and shaking his head.] “Thirty-third in a class of forty-five, I must confess, sir. I have no one to blame but myself. [Winks.] And Benny Havens.”

“After graduation in 1838 you were assigned on July 1 as a second lieutenant to the First Dragoons in Florida—to fight in the same Seminole War that would claim Lieutenant O’Brien. But the next year war had to yield temporarily to love: In August of 1839 you married your childhood sweetheart, Catherine Bryant.”

[Yearning.] “Kate! Dearest Kate. An angel upon this Earth if ever there was one. We were wed on her fourteenth birthday. Her parents disapproved. We eloped.”

[Looking down at the ground, eyes glazed.] “Dearest Kate. I wonder what became . . .”

“Catherine died in 1894, Major, in Waco.”

[Repeats dumbly.] “Died. . . . Eighteen ninety-four. From the time my life ended, hers ended forty years in the future. [Rebounding.] That means a long life. I hope it was a good one. My dearest Kate. I trust she did not long mourn my death.”

“For the rest of her life, Major, she cherished your sword and uniform.”

[Rip stares but does not speak.]

“As a young soldier you rose quickly through the ranks. Soon after your marriage you were promoted to first lieutenant.”

“As a young soldier you rose quickly through the ranks. Soon after your marriage you were promoted to first lieutenant.”

“You were cited three times for bravery against the Seminoles in Florida and brevetted to the rank of captain.

“You were cited three times for bravery against the Seminoles in Florida and brevetted to the rank of captain.

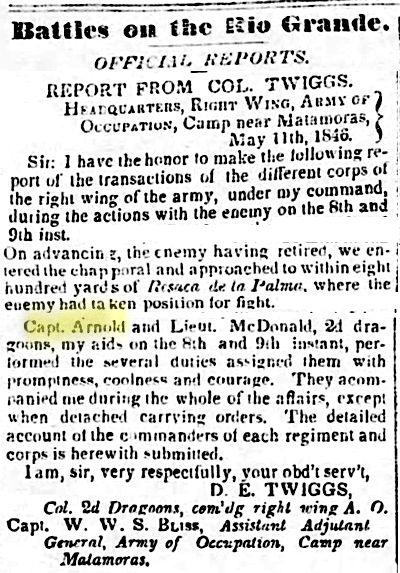

“Then came the Mexican-American War of 1846-1848.”

“You were brevetted to the rank of major in May 1846 for your performance in the Battle of Palo Alto and the Battle of Resaca de la Palma. Later that year you fought under General William Jenkins Worth at the Battle of Monterrey.”

“You were brevetted to the rank of major in May 1846 for your performance in the Battle of Palo Alto and the Battle of Resaca de la Palma. Later that year you fought under General William Jenkins Worth at the Battle of Monterrey.”

[At the mention of General Worth, Rip instinctively raises the tip of his right forefinger to the visor of his hat.]

“In 1847 you fought under General Winfield Scott at the Battle of Molino del Rey and the capture of Mexico City.”

[Closing his eyes as if to better “see” the battles.] “Yes. It all comes back to me now. Florida. Mexico. So many battles, so much blood, so many good soldiers fallen.”

“After the war you were given command of Company F of the Second Dragoons and sent to northern Texas to establish a military post. In the summer of 1849, after locating a site for the new post near the confluence of the Clear and West forks of the Trinity River, you and your men hacked that post out of the wilderness, and on June 6 you raised Old Glory over that post. Your former commander, General Worth, had just died of cholera.”

[Rip’s nostrils flare.] “General Worth! No finer soldier ever pulled on a pair of boots.”

“In fact, Major, so high was your regard for General Worth that you named the new post after your former commander.”

[Remembering.] “But looking back now, it seems I did not hold my command here long.”

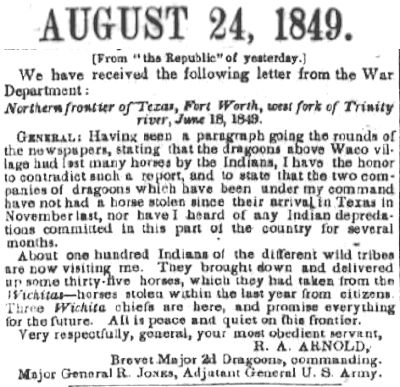

“You arrived in 1849 and withdrew in 1852. Perhaps due to the presence of you and your men here, the frontier of northern Texas was pretty quiet during your command here. You reported as much in 1849 soon after the fort was established.”

“You arrived in 1849 and withdrew in 1852. Perhaps due to the presence of you and your men here, the frontier of northern Texas was pretty quiet during your command here. You reported as much in 1849 soon after the fort was established.”

“And again in 1852, as you neared the end of your command at Fort Worth. By then the line of the frontier had shifted, and you and Company F of the Second Dragoons moved to Fort Graham.”

“And again in 1852, as you neared the end of your command at Fort Worth. By then the line of the frontier had shifted, and you and Company F of the Second Dragoons moved to Fort Graham.”

[Remembering.] “Now I recall. Then came that serpent, Dr. Steiner, and . . . but earlier you said something about ‘big day’ and ‘congratulations’?”

“Indeed, Major. Today Fort Worth—the city of Fort Worth—celebrates its birthday 173 years after you raised Old Glory at the Army fort.”

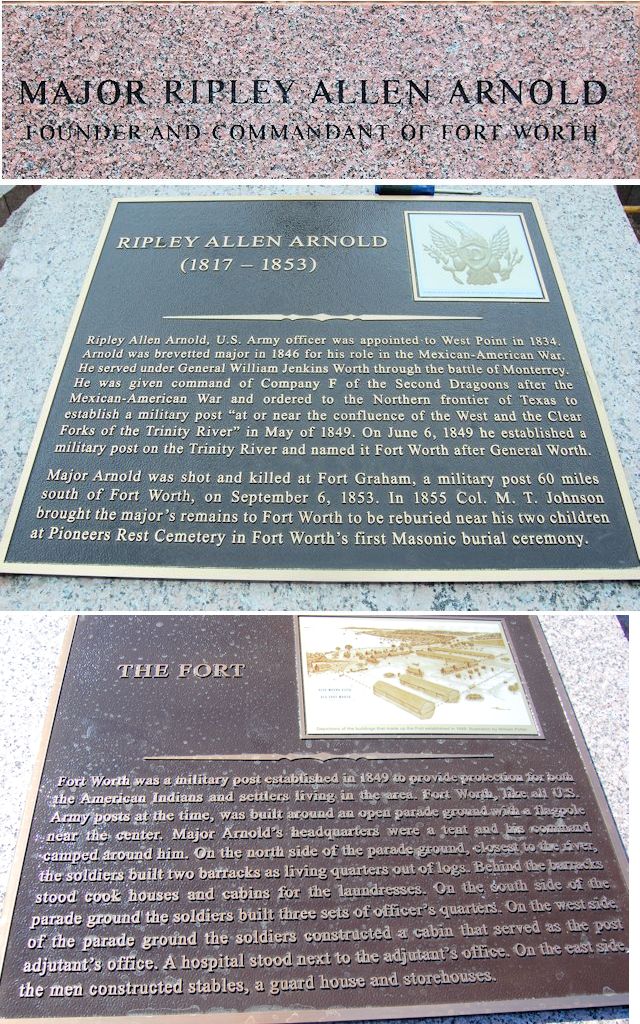

“Major, you are honored today as the founder of the city of Fort Worth. Since June 6, 2014 your statue, cast in bronze and twelve feet tall, has stood on a stone pedestal at the confluence of the Clear and West forks of the Trinity River, just below the bluff where you and your men built the fort.”

“Major, you are honored today as the founder of the city of Fort Worth. Since June 6, 2014 your statue, cast in bronze and twelve feet tall, has stood on a stone pedestal at the confluence of the Clear and West forks of the Trinity River, just below the bluff where you and your men built the fort.”

“And there’s more, Major. On the bluff a plaque commemorates the fort where it once stood.”

“And there’s more, Major. On the bluff a plaque commemorates the fort where it once stood.”

[Hands Rip a photo.] “Here, look at this.”

[Gazes at photo, remembering.] “Yes! We had just finished Fort Graham in April of forty-nine and were ordered over here to establish an outpost on the Trinity. Oh, the summer sun was merciless, and I was equally as merciless as I worked the men. But they bent their backs to their task, and how the wood chips flew.” [Looks back at the photo of the statue of himself.]

“I must say, Major, the statue is an excellent likeness of you, don’t you think? Today we don’t have many photographs of you for reference.”

[Puzzled.] “Pho-to-graphs?”

“A photo is like a daguerreotype. Like the daguerreotypes your friend Dr. Gounah made.”

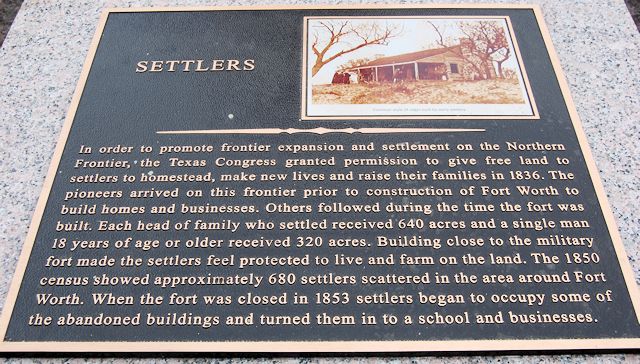

[Stares at the photo of his bronze face, unconsciously runs his hand over his cheekbones and chin whiskers.] “Twelve feet tall, you say? Bronze? A statue to honor me? I don’t know what to say. When I was at the Point, there were some statues of our great military leaders. But me? I am—I was—just a humble soldier, posted to the frontier. Just an outpost. And a short-lived one in the wilds of Texas at that. There was just a smattering of settlers here when I was . . . alive: Uncle Press Farmer, Ed Terrell, Henry Daggett, Archie Leonard.”

[Stares at the photo of his bronze face, unconsciously runs his hand over his cheekbones and chin whiskers.] “Twelve feet tall, you say? Bronze? A statue to honor me? I don’t know what to say. When I was at the Point, there were some statues of our great military leaders. But me? I am—I was—just a humble soldier, posted to the frontier. Just an outpost. And a short-lived one in the wilds of Texas at that. There was just a smattering of settlers here when I was . . . alive: Uncle Press Farmer, Ed Terrell, Henry Daggett, Archie Leonard.”

“In fact, Major, the 1850 census enumerated fewer than seven hundred settlers in the entire county.”

“In fact, Major, the 1850 census enumerated fewer than seven hundred settlers in the entire county.”

“But today, Major, Fort Worth alone has more than 900,000 people. That’s more people than your entire home state of Mississippi had in 1850. [Showing satellite photo.] You and I are where the X is on this satellite photograph. See? Fort Worth stretches for miles in all directions around you now. See what you started?”

“But today, Major, Fort Worth alone has more than 900,000 people. That’s more people than your entire home state of Mississippi had in 1850. [Showing satellite photo.] You and I are where the X is on this satellite photograph. See? Fort Worth stretches for miles in all directions around you now. See what you started?”

[Stares at photograph, trying to comprehend.] “Nine hundred thou— . . .” [Sways, almost falling off rock.]

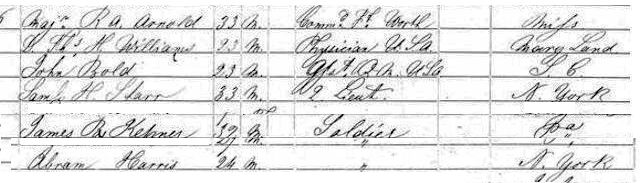

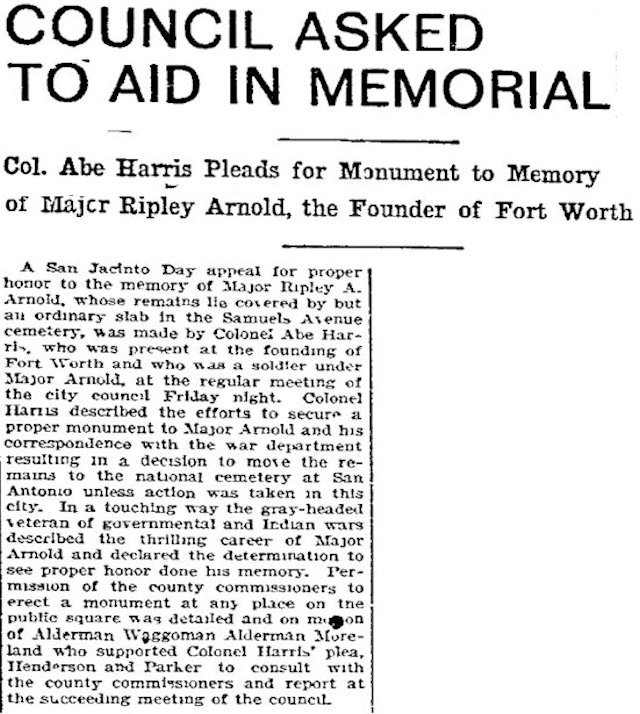

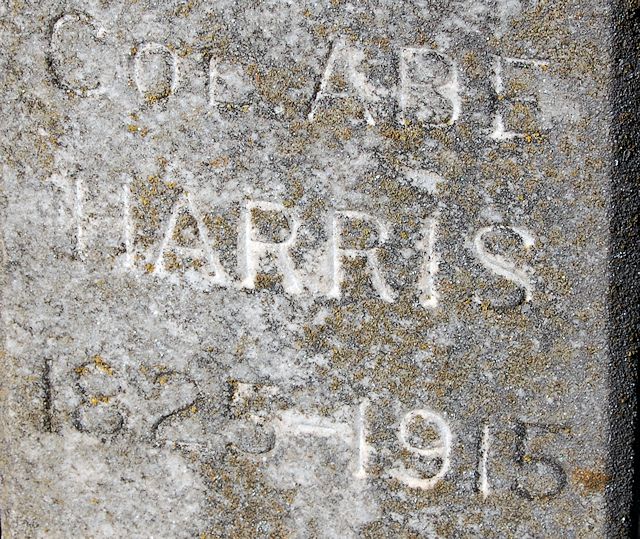

“Steady, Major. Your statue, your recognition, have been a long time coming. You remember Abe Harris? He served under you here at the fort.”

“Steady, Major. Your statue, your recognition, have been a long time coming. You remember Abe Harris? He served under you here at the fort.”

[Squints, trying to remember.] “Harris . . . Yes! Sergeant Abram Harris! Good man. Born in England, as I recollect.”

“Correct, Major. Born in Leicestershire in 1825. You have an excellent memory. Abe Harris rose to the rank of colonel in the Civil War. As this February 22—”

“Correct, Major. Born in Leicestershire in 1825. You have an excellent memory. Abe Harris rose to the rank of colonel in the Civil War. As this February 22—”

[Puzzled.] “Halt, sir! What do you mean, ‘civil war’? How can there be a civil war?”

“It’s a long story, Major. Let’s come back to that later. Now, as this February 22, 1905 article in the Fort Worth Telegram newspaper shows, in that year Colonel Harris began campaigning for a public monument to honor you.”

“Colonel Harris is buried right over there near the cemetery entrance. His headstone is very weathered now. He has been dead 107 years.”

“Colonel Harris is buried right over there near the cemetery entrance. His headstone is very weathered now. He has been dead 107 years.”

“Good ol’ Abe. I must go say hello . . . [Jumps down from rock, starts to walk, falters.] Ohhhhhhhh. I think I’d best stand at ease. It’s been a long time since I used my legs. I feel as if I’m walking home from Benny Havens.”

“Quite understandable, Major. You’ve been ‘asleep’ for 169 years, Rip. You were only thirty-six when you died. You were only thirty-two when you raised Old Glory at Fort Worth on June 6, 1849. There were thirty stars on that flag then. Today Old Glory has fifty stars.”

“Fifty!”

“The last one added was for Hawaii.”

[Puzzled.] “Ha-wa-ii?”

“You might know Hawaii as the ‘Sandwich Islands.’”

“Sandwich Islands? Yes. But those islands are over three thousand miles . . . [Suddenly Major Arnold cocks his head and listens. A low rumbling grows louder. Defensively, Arnold instinctively touches his right hand to the hilt of the sword in the scabbard on his left hip. He watches in wary amazement—as if witnessing the transit of Venus—as a diesel locomotive appears and slowly skirts the eastern edge of the cemetery on the Burlington Northern Santa Fe track one hundred feet away. He stares at the locomotive and doesn’t speak until it has passed from sight.] Upon my soul, I feel a bit light-headed. Overwhelmed, in truth. Everything you have told me, everything I have seen seems fantastic, beyond the ken of man, living or dead. [Suddenly suspicious.] And look here, reputed ‘resident of Fort Worth,’ how is it that you know all this information about me anyway? How did you get that image of this reputed colossal city of seven hundred thousand souls as if seen by the angels from the very heavens above? How did you get that colorful image of that statue of me? Even Dr. Gounah himself with his daguerreotypes could not work such magic.”

“Nothing to it these days, Major, with the Internet, a satellite, and a digital camera.”

[Baffled.] “In-ter-net? Sa-tell-ite? Di-git-al?”

“Maybe you’d better lie back down, Rip, and I’ll try to explain. You see, after you died, . . .”

[Dazed but nodding assent.] Rip lies down on the rock that covers his grave and prepares to listen. As he lies down, he begins to softly sing:

“‘Come fill your glasses, fellows, and stand up in a row

“To singing sentimentally we’re going for to go . . .”

The song “Benny Havens, Oh” at YouTube

Posts About Aviation and War in Fort Worth History

Thank you again for the great post.

For what it’s worth, I came across another interesting footnote regarding Arnold’s murder by Dr. Steiner. Dr. Steiner had a personal dislike of Arnold dating back to at least 1849. In September of 1853, Steiner and Arnold were serving together at Fort Graham. Steiner gave evidence against Arnold to a visiting lieutenant regarding the questionable sale of the government horse.

The Don Carlos Buell papers at Notre Dame include a routine order informing Steiner that he could go home on leave that month, just as soon as a new Army surgeon arrived at Fort Graham to replace him. Steiner had been on the frontier for four years without a break, and must have been eager to get on the road and travel home to (I believe) Ohio.

On the morning of September 6th, Arnold sent a subordinate with a note telling Steiner he was under arrest for drunken and rowdy behavior the night before.

This must have been a terrible blow for the doctor — by placing him in arrest, Arnold was effectively canceling his leave, possibly for months, due to the slow and cumbersome court martial process in place at the time. Additionally, a humiliating blow to his pride, from a personal enemy.

Not entirely surprising that Steiner threw the note on the ground, walked over to Arnold’s porch and reached for his gun …

Let’s automatically renew that artistic license of yours.

LOL. Thanks, Troy. I don’t think I could pass parallel parking again.

Thanks for this great post. Major Arnold traveled from Ft. Graham to the Gulf coast in 1852, en route to Washington. He apparently rode a government horse, then sold the horse on the coast, allegedly without proper authority. This sale raised some eyebrows at headquarters and an investigation was ordered.

It seems unlikely that this matter would have ended Arnold’s career. He was an experienced quartermaster and must have been thoroughly familiar with the regulations. If he were in the wrong, he probably would have gotten off with a slap on the wrist and an order to reimburse the treasury for any loss.

Feeding and transporting a horse cost money, and there were frequent disagreements over travel vouchers, allowable expenses, etc. Much like today.

I have tried to find the final report on Arnold’s sale of the horse, without success.

Thanks again for this interesting post.

Thanks, Clay. It’s a shame we have so few facts about a person so prominent in Fort Worth’s history. Thanks for your contribution.

If anyone ever does get to talk with the major, i hope it is you.

Thanks, Ron. Quite a legacy.

Two sides to every story Ava. I appreciate “Hometown’s” research and recognition of Major Arnold, as his whole body of work is indeed memorable and worthy of recognition. His heroic participation in some of the major military operations of the day are remarkable. He founded at least two forts in the wild, untamed areas of the west, and one became a major city, Ft. Worth. He was greatly respected by superiors, peers and subordinates. The ultimate feud that took his life has lots of questions surrounding it, as the surgeon who killed him had lots of friends in high places also. I will be doing a deep dive in the Texas archives to try and get to the truth of things, but Arnold’s character in no ways point to him being a horse thief. How was he to profit from extra horses in the wilderness he was instrumental in blazing? Must investigate. In any event, the Major was a stud in all his endeavors up until that fateful year. Salute.

My reply is not a reflection on your fine style for your report on Major Ripley. And what is more, you obviously did a lot of research on the subject. So my thought there is that if Paul Harvey were telling the tale, a real raconteur, would we have learned a little bit more?

You see, I take umbrage given to honor by degrees of statuary for a city, to a man whom I believe was accused of a serious crime in his day.

Ironically, in our own times, many people are insisting statues across the nation be pulled down because of their “racist” elements, yet the city of Fort Worth put up a statue and included a praising tone toward its diversity, yet all the historic evidence says there should have been no reason and logic to give him such special honor.

What’s more, you made the surgeon in your charming dialogue to be the villainous slayer of your hero, Major Ripley.

I want to point out what I consider to be interesting insights in your tale to Major Ripley’s character. You shared he was, “33rd out of 45” in rank to graduate. I am no genius, but 33rd in the academy out of a class of 45 says to me something was lacking… Now, I suspect your article is only using “artistic license” when you make an inference to the Major’s rank results coming as a result of frequent visits to Benny’s Haven, so much so that, I might infer, his real classroom during his time at the academy was at the bar. Perhaps that was even where helped to pen the memorial song.

I think old gamblers of the same historic period might have called these traits a “Tell” to his character, at least if they had played poker in the pub with the Major.

So, in telling your delightful tale, you left out the history that says the surgeon who killed the Major was taken to trial, and evidence was presented, including witnesses who were soldiers at Fort Graham. The evidence was proof that Major Ripley had defrauded the government of horses. The soldier witnesses testified that the Major had threatened the surgeon as follows, “I will put him out of the way. He shall not live to give evidence against me,”.

History tells us the doctor surgeon had filed a report against the Major for a crime he believed the Major had committed. We would call such a person today a “whistle blower”. #Metoo movement comes to mind.

Major Arnold made charges against the surgeon so to have him arrested. The surgeon denied the charges. He believed a military court martial would find him guilty. I think it is safe to infer that the Major had popularity in his favor among many in the army. After all, he was a graduate of West Point, although 33rd in his class of 45. We would probably call what the Major was trying to do,”Whistle Blower Retaliation” today.

At his civilian trial, the Army surgeon was acquitted after all the evidence was presented. And I want to clarify that the Army had sent attorneys for the prosecution. So by all accounts the Major, though already dead from the surgeon’s gunshots (isn’t it another interesting insight that the Major hero was out gunned down by the army surgeon?)the Brevet Major Ripley A Arnold, whose extensively detailed, uniform regalia, 12 foot Statue sits on panther island, was by all accounts a “Horse Thief”. And that, sir, is the Rest of the Story.

Passing the buck? Blaming some poor dead Army veteran for the boondoggle called Fort Worth. I was down slum a while back and saw a wino sleeping in the street. No, not a panther, a wino. Must put the sleeping wino figure on the cop badges. A life-size sleeping homeless person bronze statue on the courthouse lawn.

WOW, I wonder if he could see what he hath wrought upon this plain what would his thoughts be (thanks to Mike Nichols we know)

Thanks, John. What people like Arnold accomplished in a short life is just amazing. He didn’t plan it. He was just doing his job, going to the office each day. But now, 167 years later, he has a big city to show for his 9-to-5.

I was wondering why you did not include the photo of Ripley Arnold? I can’t seem to find any likenesses of his on the internet. Do you know what the sculptors based the image on? By the way, I just discovered this site…I’m a Fort Worth native and am enjoying reading the history of the city.

Thanks, David. Getting permission from private collectors (Applewhite-Clark in this case) usually means red tape (and/or expense), so I usually rely on public domain images.

Excellent information about The Major. An absolutely amazing job of research.

Thank you, Clara. I did put a lot of effort into that one. And now we have a grand new statue (even if the walk back up the bluff is a killer).

Excellent! Thank you so much for bringing this to my attention. I loved your artistic approach as having a personal conversation with Major Arnold. My great great grandfather Col. Abe also had 2 young children die during that time while married to first wife Margaret Connor. I would love to know what additional information you may have on him. Thank you again. Sharon

Thanks, Sharon. Have sent you some clips.

Mike, you are a genius. In all of your articles & pictures, I felt as though I was there. You are remarkable in your journey of Fort Worth, past, present & hopefully future. I enjoy everything you write. I have a lot more reading to do & I just had to tell you how much I enjoyed this article. Thanks a million, Mike.

Thank you so much for your kind words, Delores. I did put more thought than usual into my conversation with the major.

Congratulations Mike, another masterpiece in the works.

Thanks, Jack!

I really enjoyed this post. I loved the symbolic breaking of ether to hear you talk to the past.

Do it again!

Thank you, Genevieve. This post was special to me.

Excellent post. When will Ripley’s statue be unveiled?

Thanks, Steve. The major was long overdue.