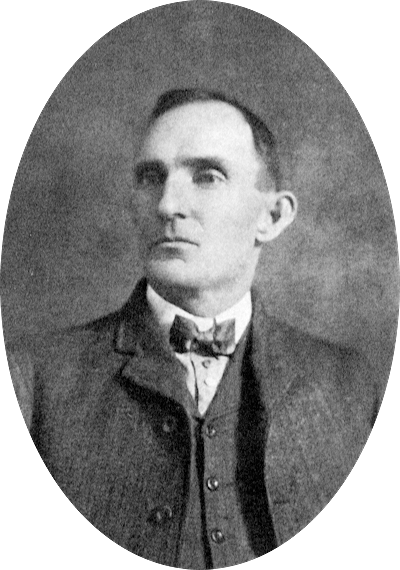

He didn’t smoke, didn’t chew, didn’t drink, didn’t curse. He attended church and read the Bible. He wore a long black coat. With his clean living, church attendance, and somber attire, some people reportedly called James Brown Miller “Deacon Miller.” Other people reportedly had another nickname for him: “Killer Miller.”

James Brown Miller, who lived the last eight years of his life in Fort Worth, is said to have killed between twenty and forty men, some in gunfights, some in assassinations. Indeed, as he was about to be lynched in 1909, he reportedly said, “Let the record show that I’ve killed fifty-one men.” (Photo from Wikipedia.)

James Brown Miller, who lived the last eight years of his life in Fort Worth, is said to have killed between twenty and forty men, some in gunfights, some in assassinations. Indeed, as he was about to be lynched in 1909, he reportedly said, “Let the record show that I’ve killed fifty-one men.” (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Another nickname for Miller could have been “Teflon Jim.” Although suspected of murder many times and charged with murder several times, he was convicted only once. But he never served time. Again and again he was acquitted on a plea of self-defense, or cases were dropped because crucial witnesses were murdered before they could testify.

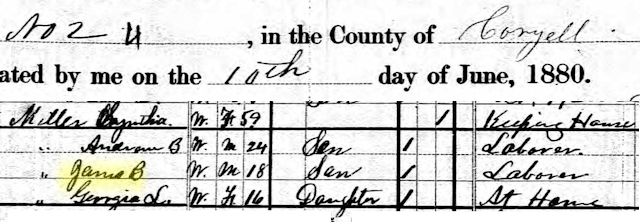

Miller was born in Arkansas in 1861, but his family soon moved to Texas. Fast-forward to 1880. Miller was living with his widowed mother in Coryell County.

Miller was born in Arkansas in 1861, but his family soon moved to Texas. Fast-forward to 1880. Miller was living with his widowed mother in Coryell County.

The 1880s for Miller would be a blur of murder and matrimony:

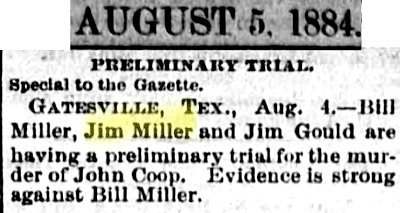

The year 1884 brought Miller his only conviction for murder. Miller was living with his sister Georgia and her husband, John Thomas Coop. Miller didn’t cotton to Coop. So, on the night of July 30 Miller reportedly was attending a revival when he slipped away, shot Coop with a shotgun as Coop slept in his bed, and returned to the revival. Jim Miller, age twenty-three, was arrested. Also arrested was Miller’s older brother Bill. (Throughout Jim Miller’s criminal career, he would be aided by men who were related to him by blood or marriage.)

The year 1884 brought Miller his only conviction for murder. Miller was living with his sister Georgia and her husband, John Thomas Coop. Miller didn’t cotton to Coop. So, on the night of July 30 Miller reportedly was attending a revival when he slipped away, shot Coop with a shotgun as Coop slept in his bed, and returned to the revival. Jim Miller, age twenty-three, was arrested. Also arrested was Miller’s older brother Bill. (Throughout Jim Miller’s criminal career, he would be aided by men who were related to him by blood or marriage.)

Jim Miller was convicted of murder. But the Texas Court of Appeals reversed the conviction on a technicality.

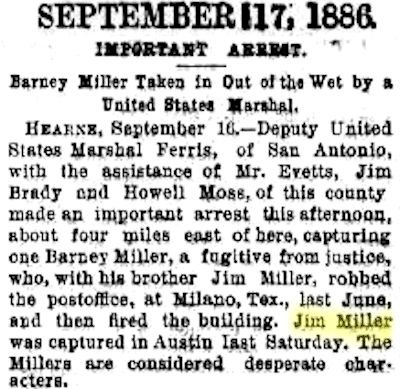

A free man, Miller joined a gang that included at least one other brother: Barney. The gang robbed trains, stagecoaches, post offices, etc., killing when necessary.

A free man, Miller joined a gang that included at least one other brother: Barney. The gang robbed trains, stagecoaches, post offices, etc., killing when necessary.

Miller also embarked on a specialty vocation: contract killing. Accounts of his fee range from $150 ($4,300 today) to $1,800 ($52,000 today).

Miller drifted into McCulloch County, where rancher Emanuel Clements Sr., cousin of outlaw John Wesley Hardin, hired him. While on the Clements ranch Miller became friends with two of Emanuel’s children: son Emanuel Jr. and daughter Sallie.

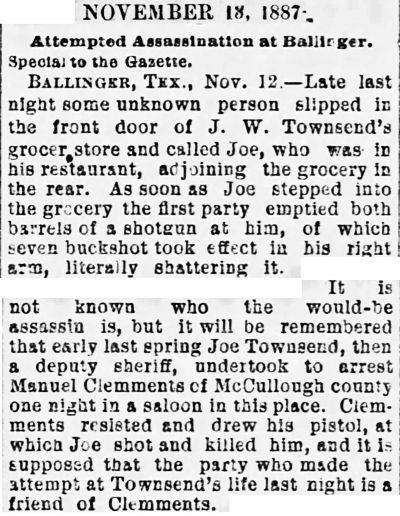

In 1887 Ballinger City Marshal Joe Townsend killed Clements Sr. Soon after, a would-be assassin armed with a shotgun ambushed Townsend. Townsend survived the blast of buckshot but lost an arm to amputation.

Killer Miller had failed to kill, but he had found his MO: ambush with a double-barrel shotgun loaded with buckshot.

Miller’s long black frock coat—which he wore regardless of the weather—concealed the shotgun and reportedly the metal breast-plate that he wore as a bullet-proof vest. (Photo from Geisterspiegel.)

Miller’s long black frock coat—which he wore regardless of the weather—concealed the shotgun and reportedly the metal breast-plate that he wore as a bullet-proof vest. (Photo from Geisterspiegel.)

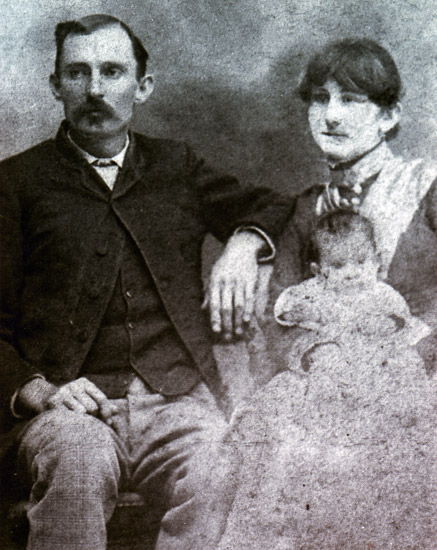

In 1888 Miller married Clements Sr.’s daughter Sallie—a second cousin of John Wesley Hardin. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

In 1888 Miller married Clements Sr.’s daughter Sallie—a second cousin of John Wesley Hardin. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

By 1891 Miller was in the west Texas town of Pecos. Reeves County Sheriff Bud Frazer hired Miller as a deputy. Miller may have regarded the badge as a license to kill. He soon earned a reputation for killing Mexicans, claiming that they had been attempting to escape.

Local gunfighter Barney Riggs—Frazer’s brother-in-law—noticed that local cattle rustling and horse theft had increased about the time Miller rode into town. Miller ostensibly spent much of his time in pursuit of the thieves but never caught any. Riggs became suspicious.

After Miller killed a Mexican prisoner who was allegedly trying to escape, Riggs told Frazer that Miller had murdered the man because he knew that Miller had stolen two mules. Frazer found the mules and fired Miller.

Thus began the Frazer-Miller feud.

In 1892 Miller ran against Frazer for the office of sheriff but lost. However, Miller was appointed city marshal of Pecos. Miller deputized his brother-in-law, Emanuel Clements Jr. Miller also befriended two gunmen: Bill Earhart and John Denson. Denson was yet another cousin of John Wesley Hardin.

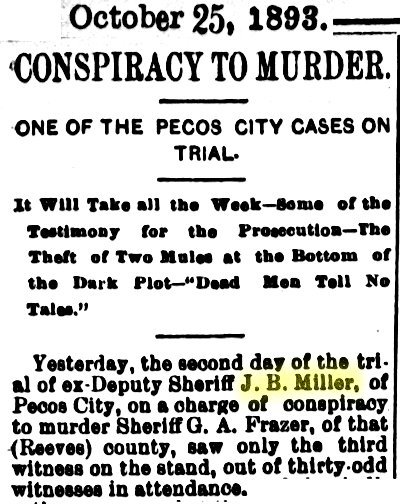

When Frazer left town briefly, Miller and his henchmen plotted to kill Frazer: When Frazer returned to town by train, Miller and associates would stage a shootout at the train station. One of the conspirators would shoot Frazer. The conspirators would claim that Frazer had been killed by a stray bullet.

But a Pecos man, Con Gibson, overheard the conspirators plotting and warned Frazer, who had the Texas Rangers arrest the conspirators. Miller and two others were indicted for conspiring to kill Frazer. But before the case came to trial, Miller henchman John Denson killed Con Gibson. As so often happened, the state was deprived of its star witness.

But a Pecos man, Con Gibson, overheard the conspirators plotting and warned Frazer, who had the Texas Rangers arrest the conspirators. Miller and two others were indicted for conspiring to kill Frazer. But before the case came to trial, Miller henchman John Denson killed Con Gibson. As so often happened, the state was deprived of its star witness.

And thus Killer Miller was acquitted.

But the Frazer-Miller feud simmered on.

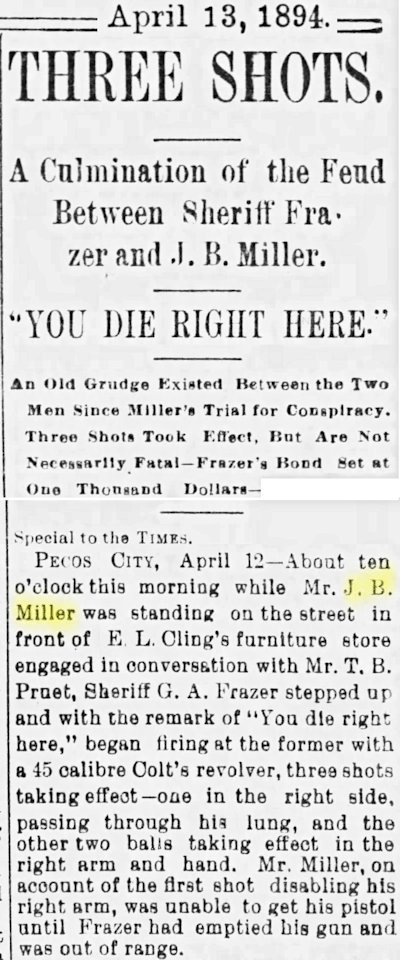

On April 18, 1894 Sheriff Frazer walked up to Miller on a street in Pecos and accused him of being involved in the murder of Con Gibson. Frazer said to Miller: “You die right here” and shot Miller three times with a Colt .45. Satisfied that Miller was dead, Frazer walked away.

On April 18, 1894 Sheriff Frazer walked up to Miller on a street in Pecos and accused him of being involved in the murder of Con Gibson. Frazer said to Miller: “You die right here” and shot Miller three times with a Colt .45. Satisfied that Miller was dead, Frazer walked away.

So did Jim Miller. His metal breast-plate had saved his life.

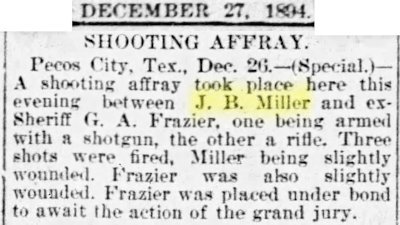

In December 1894 Miller and Frazer—by then no longer sheriff—again butted heads. This time Frazer had a rifle, Miller had his shotgun. Both men were wounded in an exchange of gunfire. Miller’s breast-plate again saved him, and he filed a complaint against Frazer for attempted murder. Frazer was placed under bond.

In December 1894 Miller and Frazer—by then no longer sheriff—again butted heads. This time Frazer had a rifle, Miller had his shotgun. Both men were wounded in an exchange of gunfire. Miller’s breast-plate again saved him, and he filed a complaint against Frazer for attempted murder. Frazer was placed under bond.

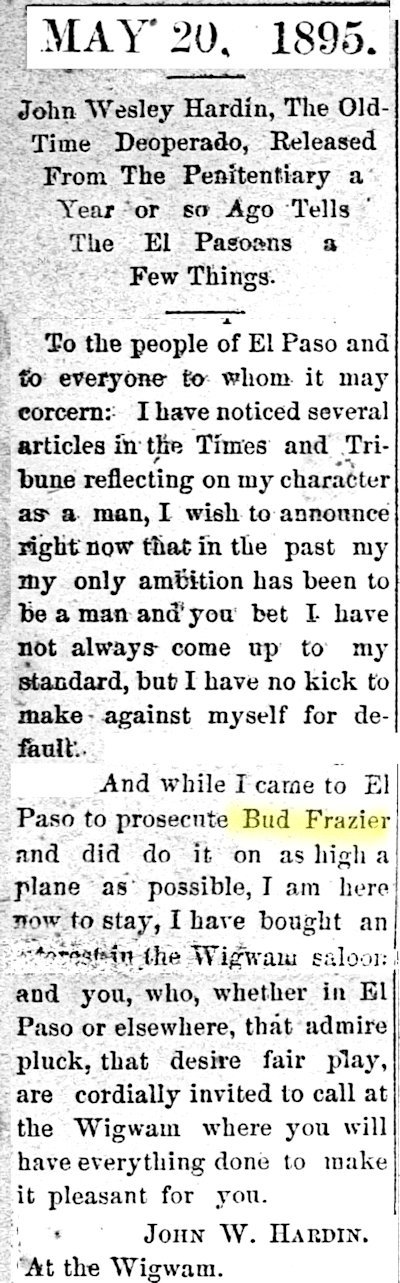

And now John Wesley Hardin finally makes a personal appearance. After seventeen years in prison, during which he studied law, Hardin was released and passed the state bar exam. In 1895 Hardin went to El Paso to prosecute Frazer on behalf of Jim Miller. Frazer, only too aware of the reputation of Miller and Hardin, convinced Governor C. A. Culberson to order a detachment of Texas Rangers to El Paso to keep the peace during the trial.

And now John Wesley Hardin finally makes a personal appearance. After seventeen years in prison, during which he studied law, Hardin was released and passed the state bar exam. In 1895 Hardin went to El Paso to prosecute Frazer on behalf of Jim Miller. Frazer, only too aware of the reputation of Miller and Hardin, convinced Governor C. A. Culberson to order a detachment of Texas Rangers to El Paso to keep the peace during the trial.

When Hardin was not in the courtroom, he was in a gambling room or saloon. One night while gambling at the Gem, Hardin suspected that the dealer was cheating him. Hardin pulled a revolver, said to the dealer, “You seem so damn cute that I believe you may hand me the money I have paid for chips,” and cocked the trigger. The dealer complied. Hardin was not pleased with local newspaper coverage of the incident and wrote a letter of complaint to an El Paso newspaper. In the letter Hardin mentioned his prosecution of Frazer. Hardin also mentioned that he had bought an interest in the Wigwam Saloon in El Paso and invited readers to drop by. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

When Hardin was not in the courtroom, he was in a gambling room or saloon. One night while gambling at the Gem, Hardin suspected that the dealer was cheating him. Hardin pulled a revolver, said to the dealer, “You seem so damn cute that I believe you may hand me the money I have paid for chips,” and cocked the trigger. The dealer complied. Hardin was not pleased with local newspaper coverage of the incident and wrote a letter of complaint to an El Paso newspaper. In the letter Hardin mentioned his prosecution of Frazer. Hardin also mentioned that he had bought an interest in the Wigwam Saloon in El Paso and invited readers to drop by. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

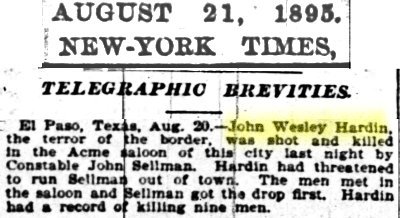

In August John Wesley Hardin was shot to death by constable/gunfighter John Selman (who, in turn, would be gunned down in 1896 in an alley next to the Wigwam Saloon).

In August John Wesley Hardin was shot to death by constable/gunfighter John Selman (who, in turn, would be gunned down in 1896 in an alley next to the Wigwam Saloon).

Bud Frazer was acquitted and returned to Pecos. The Texas Rangers left El Paso.

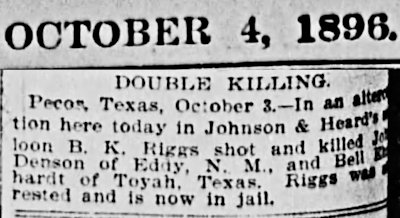

Next on Jim Miller’s grudge list was Barney Riggs, who had told Sheriff Frazer that Miller had stolen two mules in Pecos. In October 1896 Miller sent his two henchmen John Denson and Bill Earhart to kill Riggs. Riggs was working as a bartender in R. S. Johnson’s saloon when Denson and Earhart walked in. A shot from Earhart grazed Riggs, who returned fire, killing Earhart. Denson fled and ran down the street. Riggs followed and shot Denson in the back of the head. Riggs was tried for murder and acquitted.

Next on Jim Miller’s grudge list was Barney Riggs, who had told Sheriff Frazer that Miller had stolen two mules in Pecos. In October 1896 Miller sent his two henchmen John Denson and Bill Earhart to kill Riggs. Riggs was working as a bartender in R. S. Johnson’s saloon when Denson and Earhart walked in. A shot from Earhart grazed Riggs, who returned fire, killing Earhart. Denson fled and ran down the street. Riggs followed and shot Denson in the back of the head. Riggs was tried for murder and acquitted.

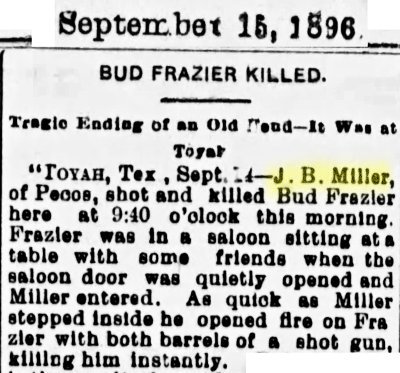

His two henchmen dead, six months later Miller got back to doing his own killing. In the nearby town of Toyah, one morning nemesis Bud Frazer was playing cards with friends in a saloon when Miller rested the barrels of his shotgun on the batwing front doors and fired, killing Frazer with two blasts of buckshot.

His two henchmen dead, six months later Miller got back to doing his own killing. In the nearby town of Toyah, one morning nemesis Bud Frazer was playing cards with friends in a saloon when Miller rested the barrels of his shotgun on the batwing front doors and fired, killing Frazer with two blasts of buckshot.

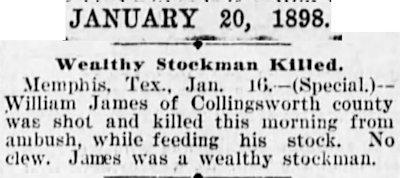

Fast-forward to 1898. Miller is said to have assassinated wealthy rancher William James in January.

Fast-forward to 1898. Miller is said to have assassinated wealthy rancher William James in January.

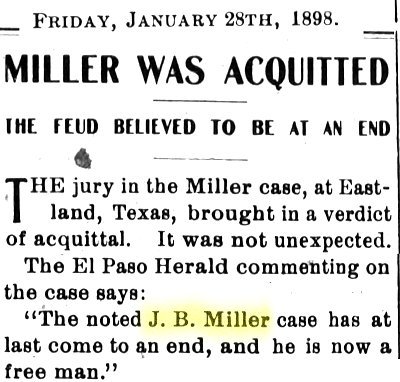

Also in January 1898 Killer Miller pleaded self-defense and was acquitted of the murder of Bud Frazer in 1896.

Also in January 1898 Killer Miller pleaded self-defense and was acquitted of the murder of Bud Frazer in 1896.

During Miller’s trial a man named “Joe Earp” (no known relation to the Earp brothers) had testified.

You guessed it: After Miller was acquitted, Joe Earp was shot dead. Miller was never charged, but some historians have carved another notch on the stock of Miller’s shotgun.

Miller next roamed up into the Panhandle, where he ran a saloon, worked as a deputy sheriff, even reportedly was briefly a special (unpaid) Texas Ranger.

In 1899 an attorney named “Stanley” claimed that Miller during his trial for killing Bud Frazer had persuaded witness Joe Earp to commit perjury, thus committing subornation of perjury.

You guessed it again: After making that claim, Stanley died of food poisoning. That was not Miller’s MO, but some historians again point a finger at Jim Miller.

That would make Stanley the sixth victim of the Frazer-Miller feud.

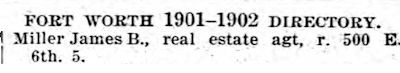

In 1901 Jim and Sallie Miller and their three children moved to Fort Worth. Mrs. Miller operated a boarding house on East Weatherford Street downtown. Jim Miller bought and sold real estate.

In 1901 Jim and Sallie Miller and their three children moved to Fort Worth. Mrs. Miller operated a boarding house on East Weatherford Street downtown. Jim Miller bought and sold real estate.

Was Killer Miller content to confine himself to title policies and closing statements?

What do you think?

Death Wore a Long Black Coat (Part 2): “Let Her Rip”

Posts About Fort Worth’s Wild West History

Posts About Crime Indexed by Decade