Happy birthday, America!

To celebrate Independence Day, . . .

To celebrate Independence Day, . . .

and the red, . . .

and the red, . . .

white, . . .

white, . . .

and bluebonnets, let’s climb into the ol’ Retroplex Cruiser time machine and take a little spin back in time.

and bluebonnets, let’s climb into the ol’ Retroplex Cruiser time machine and take a little spin back in time.

First we buckle up. Then we set the “Where?” dial for 32 degrees 46 minutes 23 seconds north, 97 degrees 19 minutes 50 seconds west. Then we set the “When?” dial for July 4, 1859. Now we press the starter, check both side mirrors (taking note of the printed warning that “historical events in mirror are closer than they appear”), and shift into reverse.

To the past, Retroplex Cruiser, and step on it!

Hold on tight and look out your viewing portal as we travel back in time to early Fort Worth: 2020 . . . 1983 (dig those mullets!) . . . 1953 (all the men are wearing hats) . . . 1925 (look: flappers) . . . 1885 (I see bustles!) . . . 1870 (stop asking “Are we there yet? Are we there yet?”) . . . 1860 (No! You should have taken care of that before we left 2022) . . . 1859 . . . December . . . August . . . July 31 . . . 19 . . . 12 . . . 5 . . . 4. Whoa!

Okay, now we’re there: July 4, 1859. Let’s get out of the Retroplex Cruiser and stretch our legs. Look around: Sure enough, we’re at the Cold Springs, which is a popular recreational area of early Fort Worth located in what will become the Samuels Avenue neighborhood. An Independence Day celebration is under way. People seem to be everywhere.

These two clips from the 1856 Dallas Herald show that the July Fourth barbecue “in a delightful grove” near the Cold Springs predates even 1859. Among civic leaders organizing the barbecue in 1856 were Ephraim Daggett, Dr. Carroll Peak, who read the Declaration of Independence, and Colonel Nat Terry, whose plantation home (described by B. B. Paddock as “of several rooms snow-white and well furnished”) is located near the Cold Springs. Terry, chairman of the celebration committee, is a former president of the Alabama state Senate.

These two clips from the 1856 Dallas Herald show that the July Fourth barbecue “in a delightful grove” near the Cold Springs predates even 1859. Among civic leaders organizing the barbecue in 1856 were Ephraim Daggett, Dr. Carroll Peak, who read the Declaration of Independence, and Colonel Nat Terry, whose plantation home (described by B. B. Paddock as “of several rooms snow-white and well furnished”) is located near the Cold Springs. Terry, chairman of the celebration committee, is a former president of the Alabama state Senate.

On this particular July Fourth, historian Julia Kathryn Garrett writes in her Fort Worth: A Frontier Triumph, the modest population of Fort Worth (fewer than five hundred) has a special reason to attend the Independence Day celebration:

Sam Houston (left photo)—hero of the Battle of San Jacinto and first elected president of the republic in 1836—and Governor Hardin Runnels are going to debate at the Cold Springs barbecue today. We are just in time. Houston, who had campaigned in Birdville in 1857 in an unsuccessful campaign for governor against Runnels, is again running for that office—and again facing Runnels, now the incumbent. (I can find no newspaper reports of campaign appearances by either candidate.)

Houston and Runnels are wealthy men—by 1859 frontier standards. But even they lack middle-class amenities of 2022: air conditioning, refrigeration, indoor plumbing, antibiotics, supermarkets, paved roads, radio, television, telephone.

Ah, but the people of 1859 can’t see from the frontier into the future. They are content: simple needs, simple pleasures.

Such as an Independence Day barbecue.

The day is hot. Texas hot. Nary a cloud. In this heat, the oak-shaded Cold Springs, with its clear, cool water, is an oasis on the prairie. Look over there where all those people are gathering. An arbor. Shade! Let’s walk over to get a closer look. The people we pass are dressed humbly, most in homemade clothes. Many of the young people are barefooted. All of the faces are white. As we walk, take a deep breath. Smell that? Fresh air. No automobile exhaust, no industrial smoke, no asphalt frying in the summer sun. Listen. Hear that? No modern sounds: no cars and trucks, no airplanes, no sirens, no lawn mowers, no amplified music. Just the lazy buzz of locusts, a mockingbird singing a medley of other birds’ greatest hits, and people talking, the language or accent of some revealing their homeland: England, Ireland, Scotland, Germany, France, Italy.

Look over there: Under a large oak tree well away from the arbor, a white-haired man of sixty-something—ancient for 1859—is playing a fiddle so softly that only he can hear it. But in a few hours he will be the center of attention.

Before the Houston-Runnels debate, a local dignitary reads the Declaration of Independence—a document today only eighty-three years old. The crowd is stilled, silent.

Then, in anticipation of the Houston-Runnels debate, people cluster in the shade of ancient oak trees and under the arbor. Look! In the shade of a majestic oak near the arbor is Sam Houston! He and Governor Runnels are standing on the bed of a wagon—an improvised speaker’s podium—that elevates them above their audience. Governor Runnels is introduced to the crowd by Middleton Tate Johnson; Houston by Colonel Terry. The debate begins. As the two candidates take turns addressing their audience, they gesture and pace about the wagon bed, causing it to rock and creak. Despite the shade, both candidates soon are sweating profusely. Houston, six-foot-six, is still a formidable figure at age sixty-six. He takes off his shirt; the governor, overheated but cognizant of the dignity of his high office, remains in his damp shirtsleeves. Each man dabs his forehead often with a handkerchief. People in the audience are fanning themselves, even in the shade of trees and under the arbor. As the two politicians debate, their listeners murmur agreement or dissent, cheer, applaud, boo; now and then a horse neighs at its hitch; a child shouts, a parent shushes. The two debaters raise their voices to be heard.

Houston is clearly the better orator.

In July 1859 John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry is only three months in the future. The issues of slavery and secession dominate conversations even in a small frontier settlement in north Texas. Governor Runnels is a secessionist (as is Colonel Terry). Houston is a unionist (as is Colonel Johnson).

Runnels advocates reopening African slave trade. Houston opposes reopening slave trade but not because he is sympathetic to African Americans.

Both men own slaves.

As Houston addresses the crowd he urges allegiance to the U.S. Constitution. “Be steadfast,” he implores the audience. The tone of his speech is mostly optimistic, but he does warn of disaster for the South if it secedes. Because Fort Worth, like much of Texas, leans toward secession, applause for Houston is polite but tempered as he delivers his closing remarks.

After the debate is concluded, Colonel Terry escorts the two candidates to his plantation house for cigars and perhaps something stronger than Cold Springs water. Runnels will spend the night at Johnson’s plantation east of Fort Worth; Houston will spend the night at Terry’s plantation before continuing his campaign trip around the state in a two-horse buggy.

The campaign rhetoric ended, the Independence Day feast begins. Food covers split-log tables under the live oaks: barbecue and other meats “cooked and seasoned so as to satisfy every taste,” breads, pies and cakes, watermelons and cider chilled in the Cold Springs. (Fort Worth won’t have the capacity to import or manufacture ice for several years, hence the attraction of the Cold Springs.)

Then comes the entertainment. According to Garrett, a tournament is held in which pairs of riders snare hoops as their horses gallop the length of a field.

In the late afternoon, as the air finally begins to cool, a dance is held under the arbor. The white-haired fiddler has become the man of the hour, the Spotify of his day. He bends to his bow, playing tunes both fast and slow—reels, schottisches, waltzes. Onlookers clap, tap their feet, and sway in time. Under the arbor each dance couple—man and woman standing side by side—moves in formations of lines, circles, and squares.

By evening holiday celebrants are dispersing by foot, by horseback, by buggy. As the pleasantly exhausted celebrants head homeward—most to log cabins—on July 4 their world looks the same as it did on July 3. But they are aware that the differences expressed in the debate they have just witnessed between unionist and secessionist are the embodiment of the differences between states, between neighbors, between even members of families. The words of Houston and Runnels seem to hang heavy in the still summer air this Independence Day evening: Ahead lies uncertainty for the nation founded on this date in 1776.

And so, before the situation becomes too strained here in 1859, let us climb back into the Retroplex Cruiser and return to the world of July 4, 2022.

Come election day on August 1, 1859, Sam Houston this time will defeat Hardin Runnels. (The votes will take almost a month to count.) Houston will take office as governor in December.

Come election day on August 1, 1859, Sam Houston this time will defeat Hardin Runnels. (The votes will take almost a month to count.) Houston will take office as governor in December.

The summer of 1860 will bring arson and lynching to Tarrant and Dallas counties.

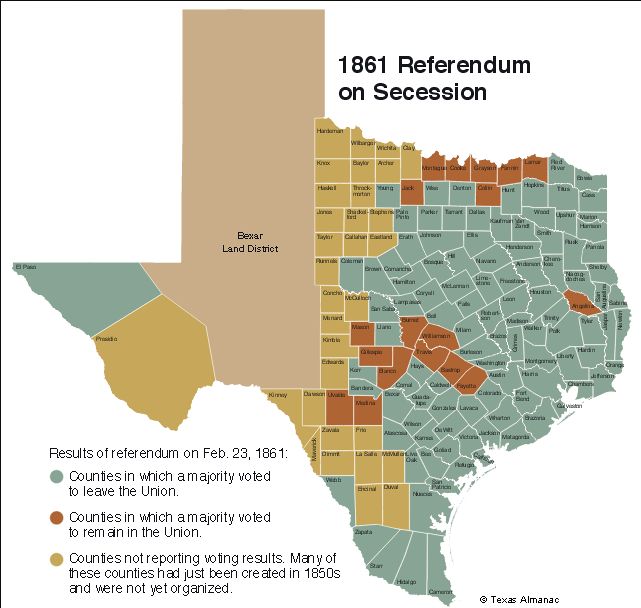

On February 1861 Texans will vote to secede from the Union, and on March 2 that secession will be formalized. That date—March 2—will be the twenty-fifth anniversary of Texas independence from Mexico; it will be Sam Houston’s sixty-eighth birthday.

On February 1861 Texans will vote to secede from the Union, and on March 2 that secession will be formalized. That date—March 2—will be the twenty-fifth anniversary of Texas independence from Mexico; it will be Sam Houston’s sixty-eighth birthday.

Two weeks later Sam Houston will refuse to take an oath of loyalty to the Confederacy and will be evicted from office.

Two weeks later Sam Houston will refuse to take an oath of loyalty to the Confederacy and will be evicted from office.

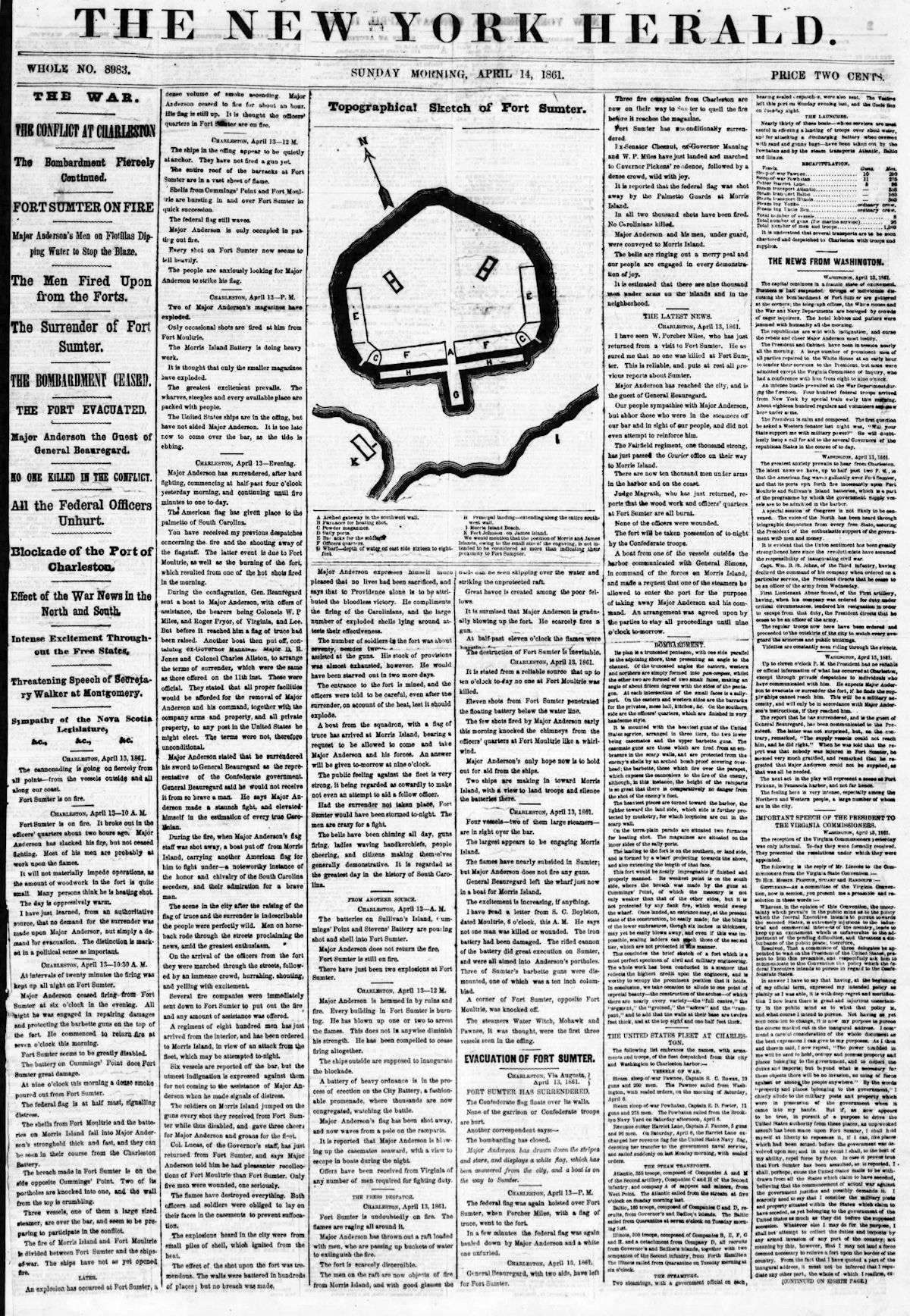

On April 12, 1861 at 4:30 a.m. Confederate batteries will open fire on the Union’s Fort Sumter.

Sam Houston will die on July 26, 1863.

Sam Houston will die on July 26, 1863.

Texas will not be readmitted to the Union until March 30, 1870.

Mike, OMG! Thank you for your astounding writing that took me back to early times in Texas. I loved hearing Big Sam debate in his run for Governor of Texas…I promise I could swear I smelled the cut trees used for the tables and I felt the sweltering heat as the day wore on. And the map of the secession of Texas, WOW! I think you should write another book so we, your faithful readers, could pick you off the bookshelf and read your mesmerizing stories whenever we felt the need. Thanks for furnishing a bright spot in the day. We surely need that these days.

Thank you so much for your kind words, Ann Gale. Ala a metal detector or geiger counter, I wish there were a Sam-o-meter we could use to detect just where at the Cold Springs Sam Houston spoke. Of course, first we’d need a Cold Springs-o-meter to determine just where the springs were!

Fourth Worth!

Beats “Forth Worth” all to heck!

Two-Shay.

OK, I know all about the Hill Country folk who were True to the Union; I revere them. I’ve read a bit about wild-eyed Methodists in Red River counties agitating as far south as Dallas. But who in the world are the dear souls who formed an island of loyalty in the sea of east TX traitors?

Fascinating map. Raises as many questions as it answers.

I wonder what many think of Houston’s comment “Texas will again lift its head and stand among the nations. It ought to do so, for no country upon the globe can compare with it in natural advantages.”

I believe he felt that the secession of 1860’s was not in benefit of Texas and it’s people, but given current climate of 10th Amendment being walked on by federal governemnt, Congress and Supreme Court, can this be a prohetic statement by Sam

God bless Houston. As he said, Texas worked too hard to become part of the Union to ever leave it.