Edward H. Tarrant was born in North Carolina in 1796 (some sources say 1792 or 1799). Still alive when he was born were George Washington, Beethoven, Napoleon, and England’s King George III.

Tarrant was born a fighter. As a soldier not yet twenty years old in 1815, Tarrant, under General Andrew Jackson, fought the Battle of New Orleans. Tarrant survived the War of 1812 and came to Texas in 1835 to fight another war: the Texas Revolution of 1836. After Texas independence he served the Republic of Texas as a Texas Ranger on the northeastern frontier.

In 1838 he was elected to the legislature of the republic from Red River County. But he found that he yearned for the life of the frontier soldier and rejoined the Rangers. He later would be an Indian agent, a delegate to the Texas convention on annexation to the United States, and a Texas state legislator.

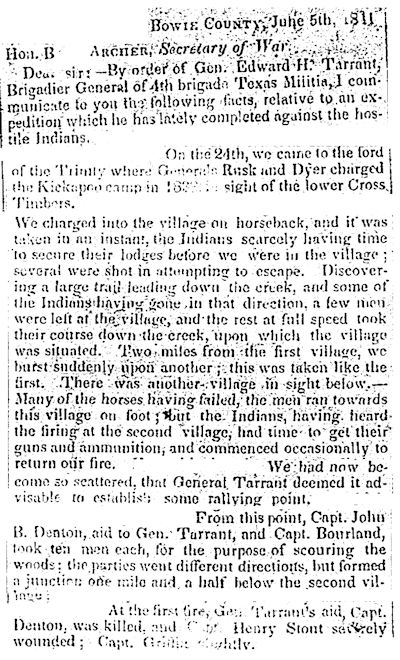

In 1841, during the days of the Republic of Texas, Tonkawa, Caddo, and Cherokee Native Americans lived in a string of villages along Village Creek in present-day Arlington. The villages were a stronghold against the advancement of white settlers. As tension between encroaching whites and entrenched Native Americans increased, the Republic of Texas ordered raids against the Village Creek Native Americans. In May 1841 General Tarrant formed a company of about seventy volunteers from the counties along the Red River. On May 14 Tarrant and his men left Fort Johnson in Grayson County and traveled southwest in what has come to be known as “Tarrant’s Expedition.” The soldiers captured a Native American who, under duress, told them where to find villages along Village Creek. Early on May 24 the soldiers attacked the southernmost village on the creek. The soldiers encountered only light opposition as they took the village by surprise and captured it. Some volunteers rode off in pursuit of villagers who had survived the attack and fled. While Tarrant and other volunteers remained behind at the captured village, captains James Bourland, John Bunyan Denton, and Henry Stout led scouts north downstream along Village Creek toward the Trinity River. The scouting party encountered increasingly larger villages and more resistance as it traveled along the creek. In a running gun battle south of the Trinity River Native American gunfire injured Henry Stout and Captain John Griffin. Methodist circuit rider/Native American fighter John B. Denton, for whom a new county would be named in 1846, was the only white fatality, killed near where today the Texas & Pacific tracks cross Rush Creek, a tributary of Village Creek.

In 1841, during the days of the Republic of Texas, Tonkawa, Caddo, and Cherokee Native Americans lived in a string of villages along Village Creek in present-day Arlington. The villages were a stronghold against the advancement of white settlers. As tension between encroaching whites and entrenched Native Americans increased, the Republic of Texas ordered raids against the Village Creek Native Americans. In May 1841 General Tarrant formed a company of about seventy volunteers from the counties along the Red River. On May 14 Tarrant and his men left Fort Johnson in Grayson County and traveled southwest in what has come to be known as “Tarrant’s Expedition.” The soldiers captured a Native American who, under duress, told them where to find villages along Village Creek. Early on May 24 the soldiers attacked the southernmost village on the creek. The soldiers encountered only light opposition as they took the village by surprise and captured it. Some volunteers rode off in pursuit of villagers who had survived the attack and fled. While Tarrant and other volunteers remained behind at the captured village, captains James Bourland, John Bunyan Denton, and Henry Stout led scouts north downstream along Village Creek toward the Trinity River. The scouting party encountered increasingly larger villages and more resistance as it traveled along the creek. In a running gun battle south of the Trinity River Native American gunfire injured Henry Stout and Captain John Griffin. Methodist circuit rider/Native American fighter John B. Denton, for whom a new county would be named in 1846, was the only white fatality, killed near where today the Texas & Pacific tracks cross Rush Creek, a tributary of Village Creek.

From Captain John B. Denton, Preacher, Lawyer and Soldier (1905): “They found his dead body where it had fallen off in the brush by the side of the trail, and not far from where he had been shot. Strange to relate, the Indians had not disturbed him, probably not knowing that they had killed any one. His friends carried him to a secluded spot away from the trail, wrapped him in a blanket, and buried him. His grave they dug with their hatchets and knives, and lined with slabs of slate rock; then they laid him tenderly in, covering him with another slab, and filled up the grave, carefully smoothing it level, and scattering leaves over it, that the Indians might not find and disturb his last resting-place.”

Denton’s burial may have been the first white burial in Tarrant County. He was later reburied in his namesake county.

In the battle of May 24, among the Native Americans of Village Creek a dozen were killed and many more injured. Meanwhile, Tarrant had discovered from Native American prisoners that the Village Creek villages had a population of one thousand warriors. The soldiers counted 225 lodges. Realizing that they were vastly outnumbered, Tarrant and company retreated, taking with them cows, horses, guns, powder, lead, blacksmithing tools, axes, saddles, buffalo robes, and other valuables from the captured village.

In July, General Tarrant, his mission unaccomplished, returned to Village Creek, this time with about four hundred men. But the villages had been abandoned.

The above newspaper clip describing the battle, from the July 14, 1841 Austin City Gazette, is a letter written to Republic of Texas Secretary of War Branch Archer.

The Battle of Village Creek is the subject of five historical markers in Arlington.

The Battle of Village Creek is the subject of five historical markers in Arlington.

1 On the seventh tee of Lake Arlington Golf Course: marker about the Native Americans who for centuries had lived along Village Creek and about the Battle of Village Creek.

2 At 6005 West Pioneer Parkway (1,500 feet west of Green Oaks Boulevard): marker about General Tarrant and the Battle of Village Creek.

3 On the eastern edge of the parking lot of Village Creek Historical Area: marker about the Native Americans who lived along Village Creek.

4 On the hike-and-bike trail in Bob Findlay Linear Park just south of Meadowbrook Boulevard: marker about the Battle of Village Creek.

5 On the hike-and-bike trail along Northwest Green Oaks Boulevard north of West Lamar Boulevard: marker about the ambush and killing of Captain John Bunyan Denton in the Battle of Village Creek.

This is the marker on the golf course. Much of the Battle of Village Creek site today lies beneath Lake Arlington.

This is the marker on the golf course. Much of the Battle of Village Creek site today lies beneath Lake Arlington.

This is the marker at 6005 West Pioneer Parkway.

This is the marker at 6005 West Pioneer Parkway.

By 1843 General Tarrant the Native American fighter had reinvented himself: General Tarrant the Indian commissioner. This hard-to-read clip from the October 7, 1843, Red-Lander newspaper of San Augustine reads:

By 1843 General Tarrant the Native American fighter had reinvented himself: General Tarrant the Indian commissioner. This hard-to-read clip from the October 7, 1843, Red-Lander newspaper of San Augustine reads:

“Correspondence.

Washington.

Sept. 23d, 1843.

A. W. Camfield:

Having received instructions from Generals Terrell and Tarrant, Indian commissioners, Mr. Eldredge left here on the 20th for the neighborhood of Bird’s Fort, in company with Colonel Tom J. Smith. Nothing has been heard from the commissioners since I last wrote you.

Yours, S.”

Some background: In 1843 President Sam Houston, governing from Washington-on-the-Brazos, the capital of the Republic of Texas, wanted to make peace with hostile tribes. He sought a treaty that would end hostilities, establish a line of demarcation between white settlers and Native Americans, and allow for trading posts along that line. Houston dispatched Joseph C. Eldridge, superintendent of Indian affairs, to visit hostile tribes and invite them to a treaty council at Bird’s Fort, which was in today’s north Arlington.

Negotiating the treaty at Bird’s Fort with Eldridge were two Indian commissioners of the republic: General Tarrant and General George W. Terrell.

The treaty was signed on September 29, 1843.

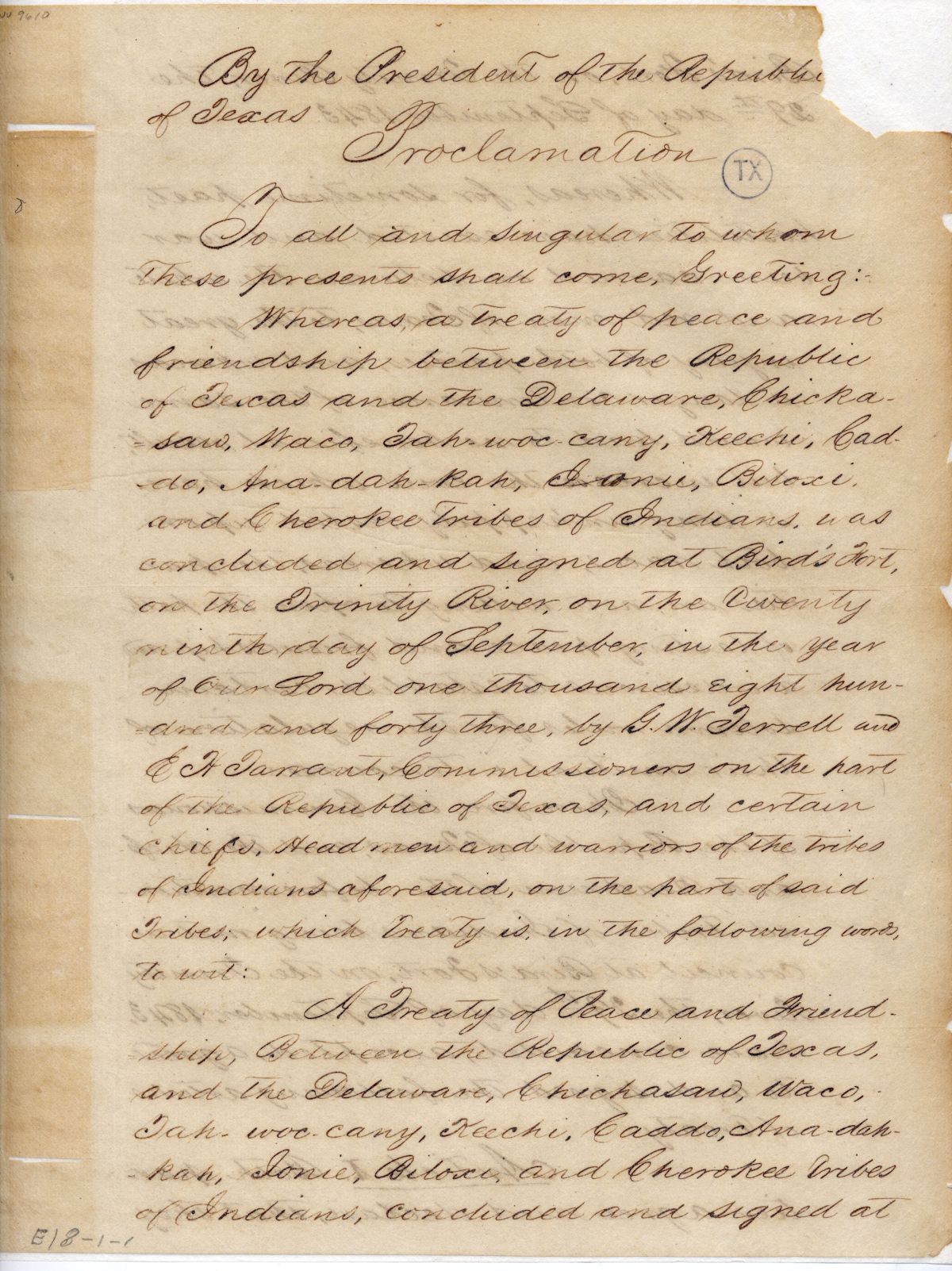

Page 1 of the treaty reads:

“By the President of the Republic of Texas

Proclamation

To all and singular to whom these presents shall come, Greeting:

Whereas, a treaty of peace and friendship between the Republic of Texas and the Delaware, Chickasaw, Waco, Tah-woc-cany, Keechi, Caddo, Ana-dah-kah, Ionie, Biloxi, and Cherokee tribes of Indians, was concluded and signed at Bird’s Fort, on the Trinity River, on the twenty ninth day of September, in the year of Our Lord one thousand eight hundred and forty three, by G.W. Terrell and E.H. Tarrant, Commissioners on the part of the Republic of Texas, and certain chiefs, Headmen and warriors of the tribes of Indians aforesaid, on the part of said Tribes; which treaty is, in the following words, to wit:

A Treaty of Peace and Friendship, Between the Republic of Texas, and the Delaware, Chickasaw, Waco, Tah-woc-cany, Keechi, Caddo, Ana-Dah-kah, Ionie, Biloxi, and Cherokee tribes of Indians, concluded and signed at”

The last page of the treaty, ratified in 1844, reads:

The last page of the treaty, ratified in 1844, reads:

“Now, Therefore, be it known That I, Sam Houston, President of the Republic of Texas, having seen and considered said Treaty, do, in pursuance of the advice and consent of the Senate, as expressed by their resolution of the thirty first of January, one thousand eight hundred and forty

four, accept, ratify and confirm the same, and every clause and article thereof.

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the Great Seal of the Republic to be affixed

Done at the town of Washington [-on-the-Brazos], this third day of February in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and forty four and of the Independence of the Republic the Eighth.

By the President

Sam Houston

Anson Jones

Secretary of State”

(Photos from Texas State Library & Archives Commission.)

From Wikipedia, a summary of some of the treaty’s twenty-four articles:

Article I. The parties will “forever live in peace” and “meet as friends and brothers. The existing state of war shall cease and never be renewed.”

Article VII. No white man may sell or provide “ardent spirits or intoxicating liquors” to the Indians.

Article X. No trader may furnish any “warlike stores” to the Indians without the permission of the President of Texas.

Article XIII. Any white man who kills an Indian or commits an outrage against an Indian shall be punished for a felony.

Article XIV. If an Indian kills a white person, he will be punished by death. If an Indian steals the property of a white man, he shall be punished by the tribe.

Article XVIII. The President of Texas may “send among the Indians” blacksmiths and other mechanics and schoolmasters for the purpose of instructing the Indians in English and Christianity.

Article XXII. After the Indians have shown that they will keep the treaty and not make war upon the whites, the President will authorize the traders to sell arms to the Indians and to provide gifts to the Indians.

Article XXIV. The President will make all arrangements and regulations with the Indians as he sees fit “for their peace and happiness.”

Article I’s declaration that both sides would “forever live in peace” didn’t come to pass, and five years later Texas, by then part of the Union, was deemed to need more forts along the frontier of northern Texas, one of which, of course, was Fort Worth.

Marker is in River Legacy Park, Arlington.

Marker is in River Legacy Park, Arlington.

When Tarrant County was created in 1849 it was named for General Tarrant in recognition of his Native American-fighting career, especially Tarrant’s Expedition at Village Creek. Tarrant never lived in his namesake county.

Tarrant died on August 2, 1858. Clip is from the August 11 Dallas Weekly Herald.

Tarrant died on August 2, 1858. Clip is from the August 11 Dallas Weekly Herald.

Fellow Masons paid tribute to General Tarrant. Clip is from the August 21, 1858 Dallas Weekly Herald.

Fellow Masons paid tribute to General Tarrant. Clip is from the August 21, 1858 Dallas Weekly Herald.

General Tarrant originally was buried in Parker County, then reburied on his farm in Ellis County, and finally came to a stop in Pioneers Rest Cemetery on Samuels Avenue in March 1928. Clip is from the March 9, 1859 Dallas Weekly Herald.

General Tarrant originally was buried in Parker County, then reburied on his farm in Ellis County, and finally came to a stop in Pioneers Rest Cemetery on Samuels Avenue in March 1928. Clip is from the March 9, 1859 Dallas Weekly Herald.

General Tarrant had been in Pioneers Rest Cemetery only three months when his grave was decorated for Memorial Day in 1928.

General Tarrant had been in Pioneers Rest Cemetery only three months when his grave was decorated for Memorial Day in 1928.

In 1930 a fund was started to raise money for a granite memorial to honor General Tarrant.

In 1930 a fund was started to raise money for a granite memorial to honor General Tarrant.

The memorial was installed in 1932.

The memorial was installed in 1932.

“Tarrant County is his monument.”

“Tarrant County is his monument.”