In August 1873 Fort Worth’s future looked as bright as a locomotive’s headlight:

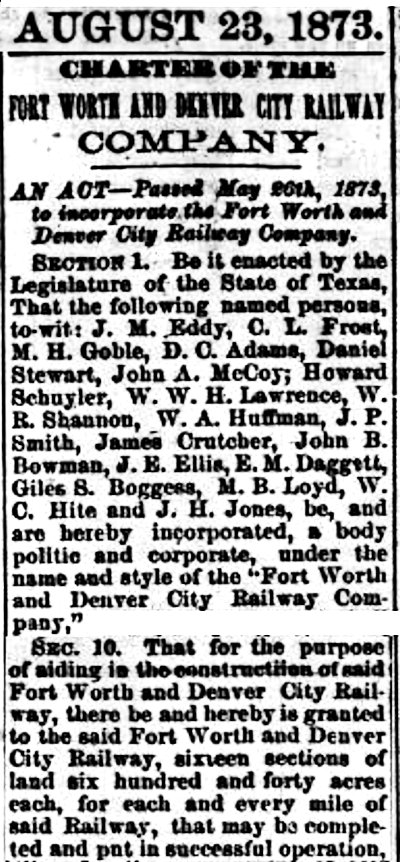

In May Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt, representing Fort Worth in the Texas legislature, had gotten special legislation passed chartering the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad to establish rail service between those two cities. The FW&DC would lay track northwestward from Fort Worth to connect with track laid southeastward from Denver by the Denver & New Orleans railroad. By connecting Fort Worth to Denver, the FW&DC also would be the first railroad to serve the Panhandle.

In May Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt, representing Fort Worth in the Texas legislature, had gotten special legislation passed chartering the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad to establish rail service between those two cities. The FW&DC would lay track northwestward from Fort Worth to connect with track laid southeastward from Denver by the Denver & New Orleans railroad. By connecting Fort Worth to Denver, the FW&DC also would be the first railroad to serve the Panhandle.

Incorporators of the company included E. M. Daggett, Martin Bottom Loyd, Walter A. Huffman, John Peter Smith, and James Franklin Ellis. Note that the state promised to grant the railroad sixteen sections of land for each mile of track laid. That promise was a factor in the railroad’s plan for financing.

Granted, connecting Fort Worth to Denver was an ambitious project: eight hundred miles. The FW&DC would lay about five hundred miles, the D&NO about three hundred. The two railroads hoped to complete the track in six years.

But Fort Worth civic leaders knew that railroads were the midwives of prosperity. Fort Worth would be enriched. And other towns would develop as the FW&DC built depots and roundhouses and repair shops along the way, luring workers and their families, creating the need for stores, banks, saloons, schools.

Fort Worth could be connected to those new towns long before the FW&DC track reached Denver.

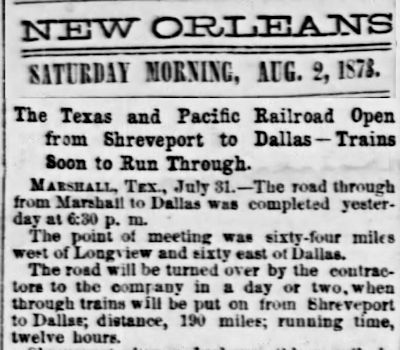

Meanwhile, Fort Worth’s future appeared to be even closer: The Texas & Pacific railroad, laying track from Longview westward toward Fort Worth, had reached Dallas on July 30, 1873.

Meanwhile, Fort Worth’s future appeared to be even closer: The Texas & Pacific railroad, laying track from Longview westward toward Fort Worth, had reached Dallas on July 30, 1873.

The T&P was now just thirty miles from Fort Worth. Track crews could lay thirty miles in a month.

The Texas & Pacific track would be the first leg on B. B. Paddock’s tarantula. Might the Fort Worth & Denver City track be the second leg?

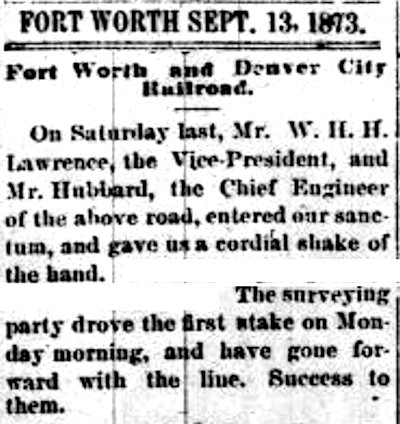

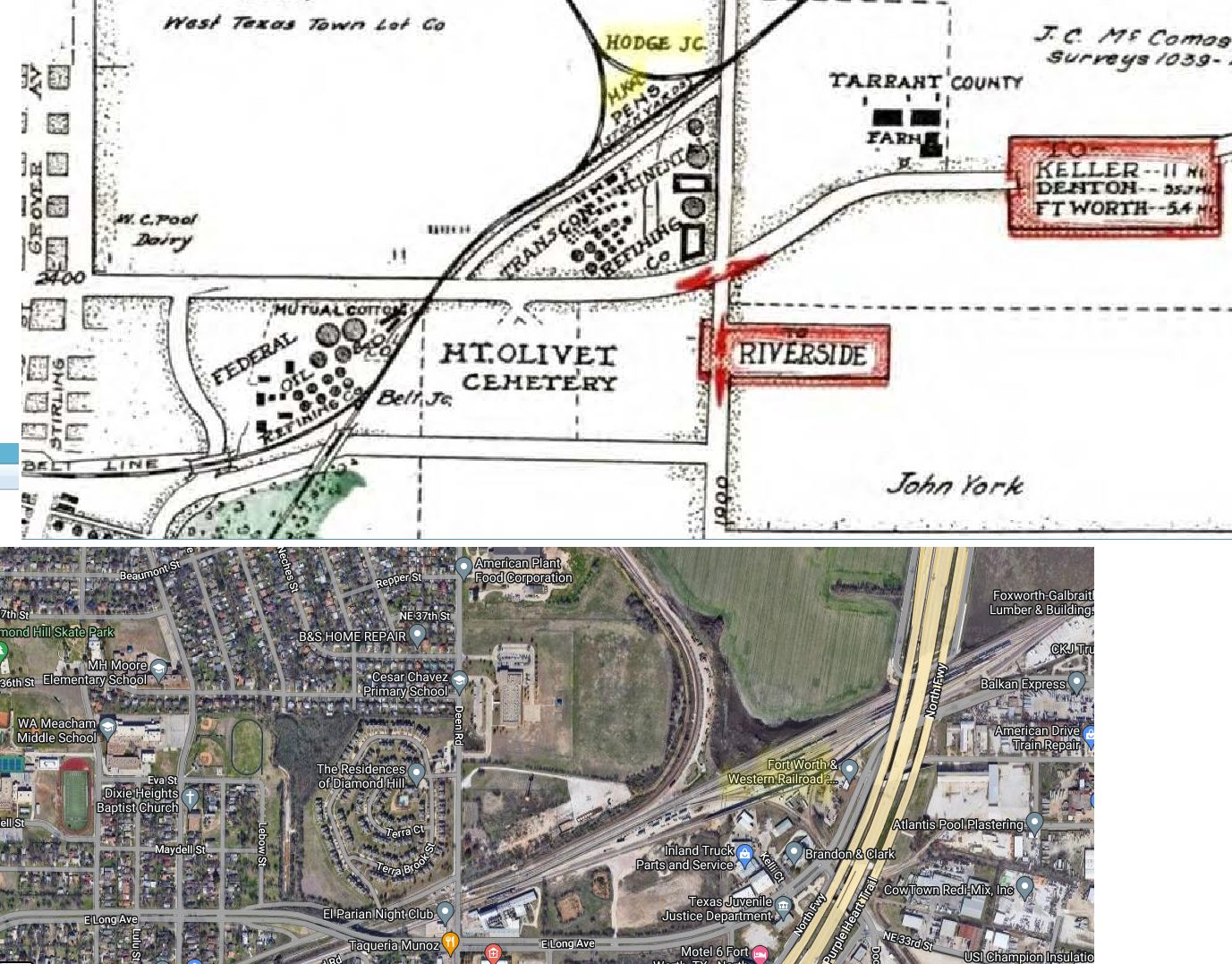

As if to answer that question, one week after the T&P reached Dallas, the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad began surveying right-of-way toward Denver. On September 6 a survey stake was driven at Hodge junction about four miles north of downtown Fort Worth.

As if to answer that question, one week after the T&P reached Dallas, the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad began surveying right-of-way toward Denver. On September 6 a survey stake was driven at Hodge junction about four miles north of downtown Fort Worth.

Hodge was a junction on the Katy track just north of today’s Mount Olivet Cemetery and west of the county poor farm. Today the junction (no longer a three-sided “wye”) is the site of a Fort Worth & Western railroad yard. Note that the Missouri-Kansas-Texas (Katy) railroad had a small stock pen at Hodge.

Hodge was a junction on the Katy track just north of today’s Mount Olivet Cemetery and west of the county poor farm. Today the junction (no longer a three-sided “wye”) is the site of a Fort Worth & Western railroad yard. Note that the Missouri-Kansas-Texas (Katy) railroad had a small stock pen at Hodge.

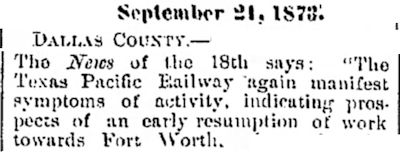

Meanwhile, on the T&P track in Dallas, on September 18 the Dallas News forecast “early resumption of work towards Fort Worth.”

Meanwhile, on the T&P track in Dallas, on September 18 the Dallas News forecast “early resumption of work towards Fort Worth.”

But then came the double whammy of 1873.

But then came the double whammy of 1873.

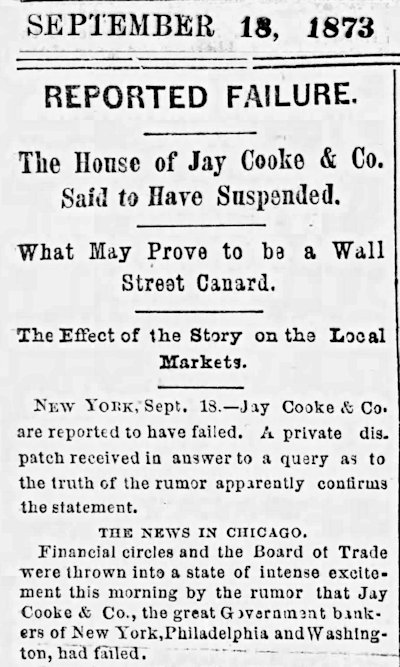

On September 18—the very day the Dallas News had forecast “early resumption of work towards Fort Worth” from Dallas by Texas & Pacific—Fort Worth’s future was blindsided by developments far, far away in the East.

Jay Cooke & Company, a major U.S. bank, failed—in part because of speculation in railroads. The Cooke failure rippled through the financial industry. The New York Stock Exchange closed for ten days. Between 1873 and 1875 eighteen thousand businesses—including many insurance companies—would fail. Unemployment in 1878 would hit 8.25 percent. Building construction would slow, wages would be cut, real estate values would fall, corporate profits would vanish.

And Fort Worth’s future would be shunted onto a siding.

The panic hit the railroad industry like a ten-pound hammer. By November 1873 fifty-five railroads had failed, and another sixty would go bankrupt within a year. Construction of new rail lines would fall from 7,500 miles of track in 1872 to just 1,600 miles in 1875.

Work stopped on both the Texas & Pacific and Fort Worth & Denver City railroads.

Double whammy.

Fast-forward three years. Despite the financial panic, in 1876 Fort Worth took the cowcatcher by the horns. With a “get ’er done” attitude that would serve Fort Worth well in the future, citizens raised money to form the Tarrant County Construction Company, headed by Van Zandt, Jesse Zane-Cetti, John Hirschfield, and Walter A. Huffman, to grade the Texas & Pacific roadbed from Dallas County to Fort Worth and install bridges and culverts. All the T&P had to do was lay the track and put the rolling stock on that track.

On July 19, 1876 Fort Worth’s future finally rolled into town.

But the FW&DC was still stalled at Hodge junction.

Fast-forward five years.

Enter General Grenville Mellen Dodge (1831-1916), one of the master railroad builders of the nineteenth century. He had been the Union Pacific railroad’s chief engineer as the first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869. He had been the ramrod pushing the T&P from Longview to Dallas in 1873 (and ultimately to Fort Worth in 1876). And now, in 1881, he was the ramrod pushing the T&P west from Fort Worth toward El Paso, there to meet the Southern Pacific railroad and form the nation’s second transcontinental railroad. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Enter General Grenville Mellen Dodge (1831-1916), one of the master railroad builders of the nineteenth century. He had been the Union Pacific railroad’s chief engineer as the first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869. He had been the ramrod pushing the T&P from Longview to Dallas in 1873 (and ultimately to Fort Worth in 1876). And now, in 1881, he was the ramrod pushing the T&P west from Fort Worth toward El Paso, there to meet the Southern Pacific railroad and form the nation’s second transcontinental railroad. (Photo from Wikipedia.)

Now Dodge again became Fort Worth’s iron angel. In 1881 he jumpstarted the stalled FW&DC project by forming a construction company to lay track from Fort Worth.

Roy H. Kimble, who worked forty-six years for the Fort Worth & Denver City, recalled of Dodge: “He proposed to the stockholders to build, furnish all material, and to equip the road to Denver, any point in Colorado, or into the Indian Territory for $20,000 a mile in stock and the same amount in bonds. The stockholders accepted his offer, and a contract was signed on April 29, 1881.”

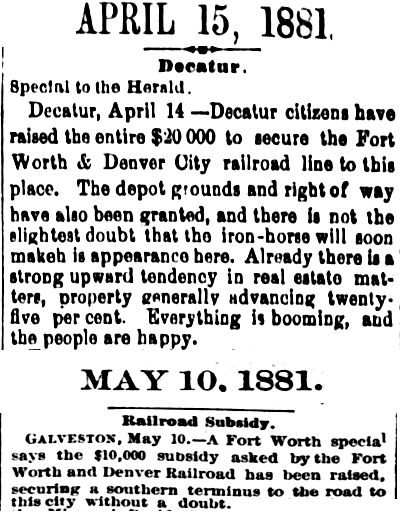

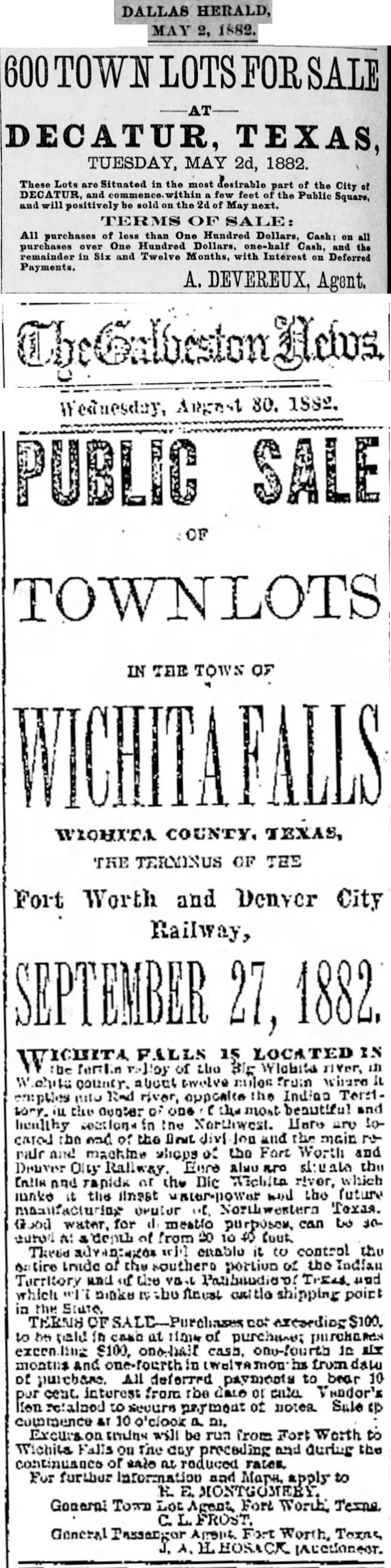

Towns were keenly aware of the economic benefits of being served by a railroad. Towns often paid a subsidy to a railroad company and donated land for a depot, railyard, etc. to induce the company to lay track through them. The FW&DC received $10,000 from Fort Worth, $20,000 from Decatur.

Towns were keenly aware of the economic benefits of being served by a railroad. Towns often paid a subsidy to a railroad company and donated land for a depot, railyard, etc. to induce the company to lay track through them. The FW&DC received $10,000 from Fort Worth, $20,000 from Decatur.

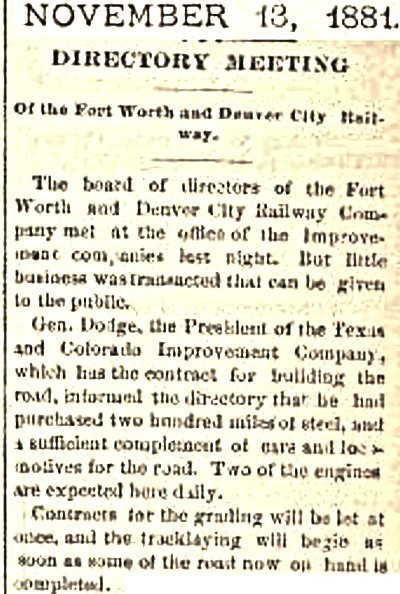

In November General Dodge told the FW&DC board of directors that grading and track-laying toward Decatur would begin soon.

In November General Dodge told the FW&DC board of directors that grading and track-laying toward Decatur would begin soon.

But before work could begin, the FW&DC received another blow.

Kimble wrote: “In 1882 the state of Texas withdrew the then current offer to give sixteen sections of land for every mile of railroad built in the state. . . . A number of Texas railroads . . . received sixteen sections or 10,240 acres of Texas land for each mile of railway constructed. The Fort Worth and Denver City Railway . . . got none of this premium.”

Railroad companies relied on the sale of such state grant land to finance construction.

General Dodge and the FW&DC officers swallowed their disappointment and began laying track anyway.

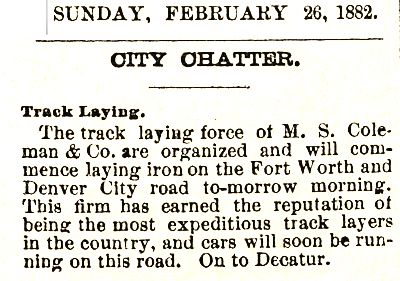

In February 1882 track-laying began. “On to Decatur.”

In February 1882 track-laying began. “On to Decatur.”

The FW&DC reached Decatur in April and on May 1 began running two trains a day between Fort Worth and Decatur: forty miles. The FW&DC could now consider itself a leg—albeit a stubby one—on Paddock’s tarantula.

The FW&DC reached Decatur in April and on May 1 began running two trains a day between Fort Worth and Decatur: forty miles. The FW&DC could now consider itself a leg—albeit a stubby one—on Paddock’s tarantula.

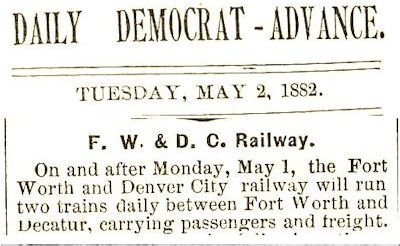

But the FW&DC was not the second leg of the tarantula. Far from it. By 1879 the pressure of the financial panic of 1873 had eased, and railroads had begun to lay track again. Fort Worth had continued to woo railroads to town. In fact, as the above time table shows, by the time the FW&DC reached Decatur in May 1882, Paddock’s tarantula had six other legs.

But the FW&DC was not the second leg of the tarantula. Far from it. By 1879 the pressure of the financial panic of 1873 had eased, and railroads had begun to lay track again. Fort Worth had continued to woo railroads to town. In fact, as the above time table shows, by the time the FW&DC reached Decatur in May 1882, Paddock’s tarantula had six other legs.

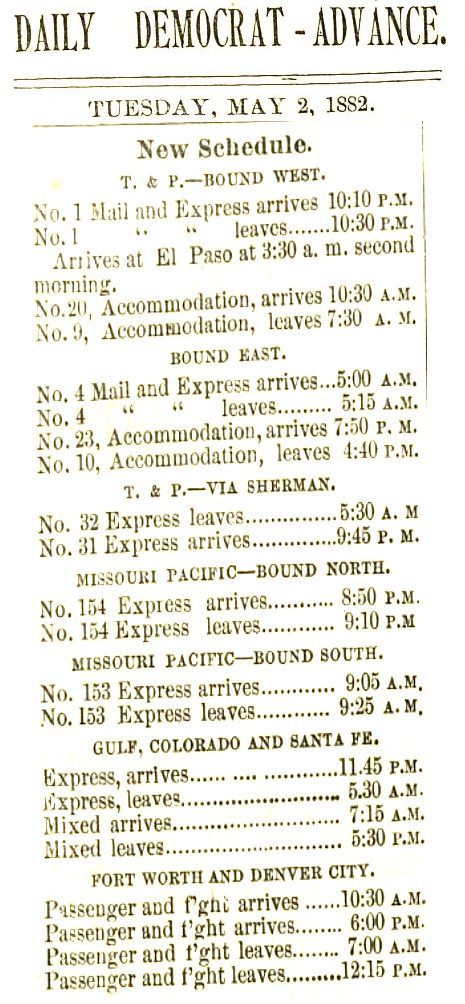

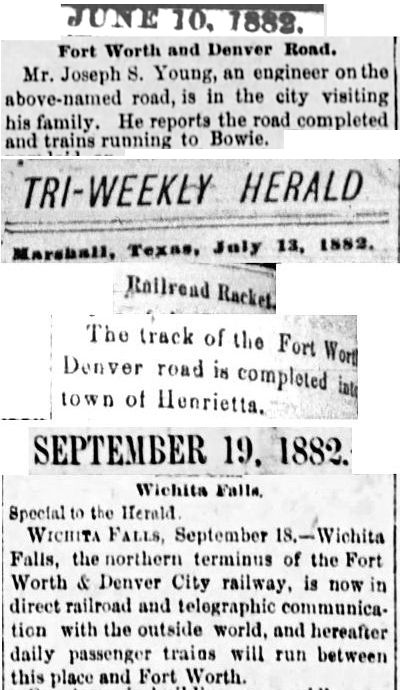

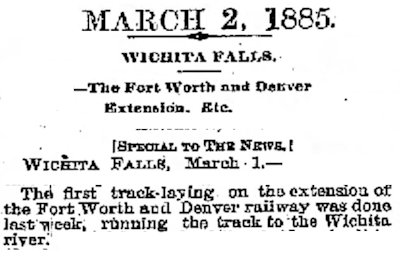

General Dodge and his crew pressed on from Decatur: Bowie, Henrietta, Wichita Falls. Note that the Wichita Falls clip says the city was “now in direct railroad and telegraphic communication with the outside world.” Railroad companies strung telegraph lines along their right-of-way as they laid track, thus bringing both transportation and communication to the cities along the track.

General Dodge and his crew pressed on from Decatur: Bowie, Henrietta, Wichita Falls. Note that the Wichita Falls clip says the city was “now in direct railroad and telegraphic communication with the outside world.” Railroad companies strung telegraph lines along their right-of-way as they laid track, thus bringing both transportation and communication to the cities along the track.

The railroad brought economic activity to each town, whether new or established, as town lots were sold.

The railroad brought economic activity to each town, whether new or established, as town lots were sold.

But at Wichita Falls in July 1882 track-laying stopped.

J. M. Eddy, president of the Fort Worth & Denver City, said General Dodge’s crew would not lay track beyond Wichita Falls until the Denver & New Orleans—the railroad laying track from Colorado toward Texas—reached the Canadian River in Texas. The D&NO had gotten only as far as Pueblo—120 miles—when it stopped laying track. In 1885 the company went bankrupt and was sold at auction.

And thus for three years Wichita Falls was the northern terminus of the FW&DC line, just as Fort Worth had been on the T&P line from 1876 to 1880.

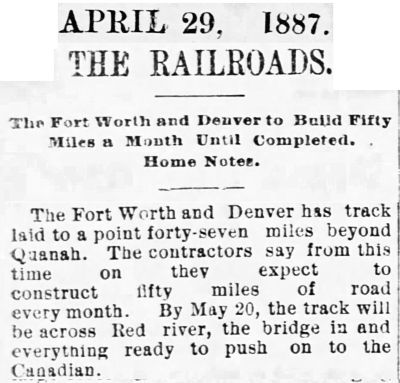

In 1885 a new company—Denver, Texas & Gulf—took over the D&NO’s half of the project and began laying track.

And so did General Dodge. Grading for construction beyond Wichita Falls began in February.

And so did General Dodge. Grading for construction beyond Wichita Falls began in February.

By May 5, 1885 the FW&DC had reached Harrold.

Then on to Vernon, Chillicothe, Quanah.

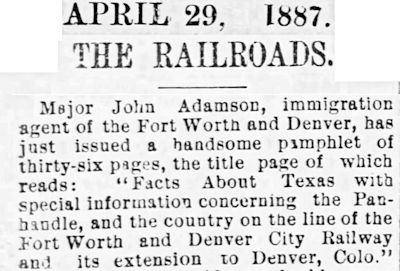

In April 1887 the track was forty-seven miles beyond Quanah. Contractors said they expected to lay fifty miles of track a month.

In April 1887 the track was forty-seven miles beyond Quanah. Contractors said they expected to lay fifty miles of track a month.

Texas, especially areas such as the Panhandle, was still being settled in the 1880s. Railroad companies—especially those that received land from the state to sell—published immigrant guides that extolled the virtues of the area that the railroads laid track through.

Texas, especially areas such as the Panhandle, was still being settled in the 1880s. Railroad companies—especially those that received land from the state to sell—published immigrant guides that extolled the virtues of the area that the railroads laid track through.

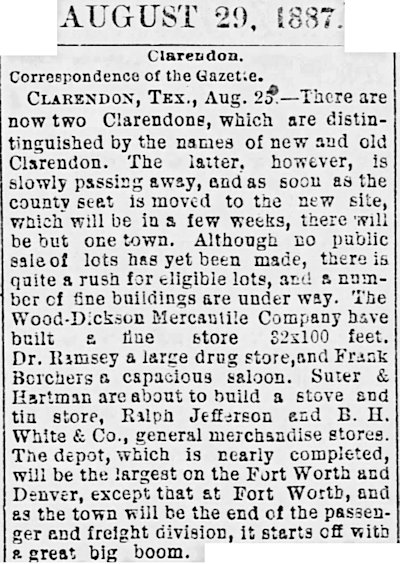

If the locomotive will not come to Muhammad, then Muhammad must go to the locomotive: When the FW&DC planned to miss the town of Clarendon by six miles, townspeople moved the town to the track.

If the locomotive will not come to Muhammad, then Muhammad must go to the locomotive: When the FW&DC planned to miss the town of Clarendon by six miles, townspeople moved the town to the track.

Then came Washburn (named for FW&DC official D. W. Washburn), Amarillo, the Canadian River.

The saga of the Fort Worth & Denver City was followed even in England.

The saga of the Fort Worth & Denver City was followed even in England.

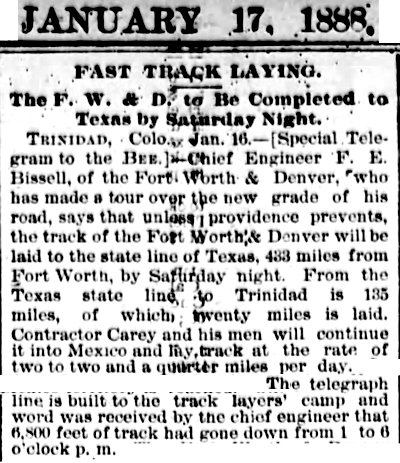

On January 16, 1888 a FW&DC engineer said the track probably would reach the Texas border by January 21. The contractor said his men would lay two-plus miles of track a day. In one five-hour span they laid 6,800 feet!

On January 16, 1888 a FW&DC engineer said the track probably would reach the Texas border by January 21. The contractor said his men would lay two-plus miles of track a day. In one five-hour span they laid 6,800 feet!

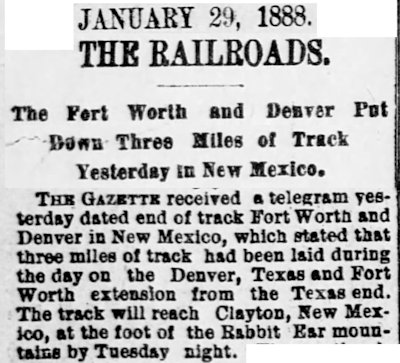

The Fort Worth & Denver City share of the track and the Denver, Texas & Gulf share of the track were supposed to meet at the Texas-New Mexico border. When General Dodge reached the border ahead of the other team, he kept right on going, laying track into New Mexico.

The Fort Worth & Denver City share of the track and the Denver, Texas & Gulf share of the track were supposed to meet at the Texas-New Mexico border. When General Dodge reached the border ahead of the other team, he kept right on going, laying track into New Mexico.

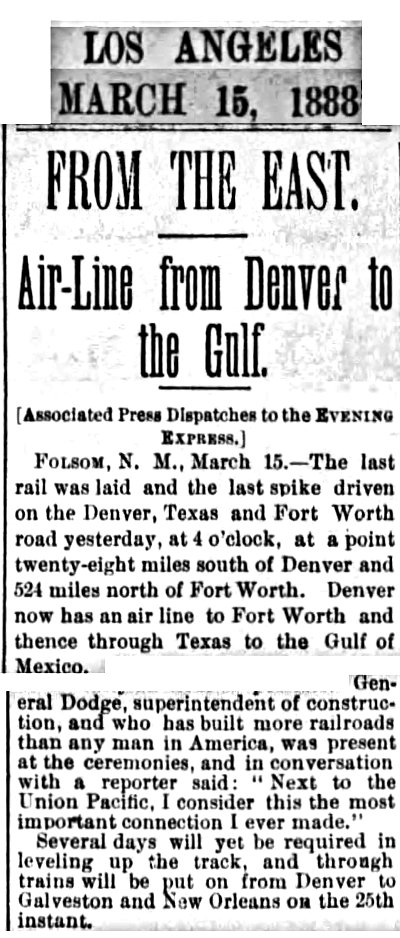

On March 14, 1888 the two tracks met at Folsom, New Mexico 528 miles from Fort Worth.

On March 14, 1888 the two tracks met at Folsom, New Mexico 528 miles from Fort Worth.

General Dodge drove the last spike.

Dodge said, “Next to the Union Pacific, I consider this the most important connection I ever made.”

Fifteen years after the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad was chartered, its track finally connected its namesake cities.

The eight hundred-mile train trip between Fort Worth and Denver took thirty-six hours.

The effect of railroads was exponential. Because Fort Worth was a railroad hub, the FW&DC line didn’t connect Denver to just Fort Worth. After a Denver traveler reached Fort Worth he could connect to trains going to the Gulf coast, to New Orleans, to St. Louis, even to California via the transcontinental line that General Dodge had ramrodded in 1882.

(In the clipping, “twenty-eight miles” should be “280 miles.”)

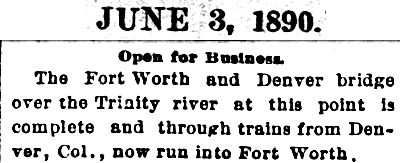

Two years after reaching Denver, the FW&DC laid its own track between Hodge junction and downtown Fort Worth, where it had its own depots and yard.

Two years after reaching Denver, the FW&DC laid its own track between Hodge junction and downtown Fort Worth, where it had its own depots and yard.

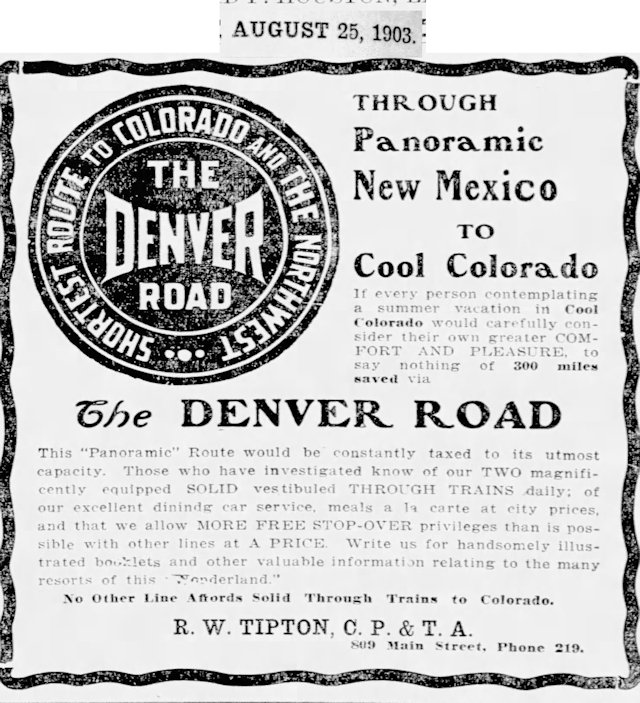

The Fort Worth & Denver City railroad soon became known as the “Denver Road.”

The Fort Worth & Denver City railroad soon became known as the “Denver Road.”

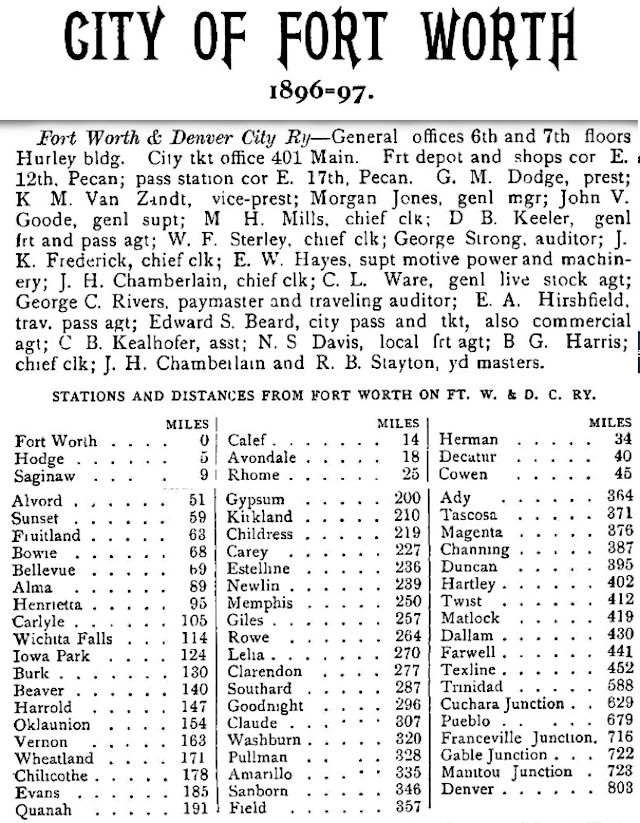

The 1906 city directory lists the stations and distance between Fort Worth and Denver. By 1906 General Dodge was president of the company. K. M. Van Zandt was vice president.

The 1906 city directory lists the stations and distance between Fort Worth and Denver. By 1906 General Dodge was president of the company. K. M. Van Zandt was vice president.

In 1908 the FW&DC was acquired by the Burlington railroad.

In 1908 the FW&DC was acquired by the Burlington railroad.

In 1925 the FW&DC began service to Dallas on the Rock Island track.

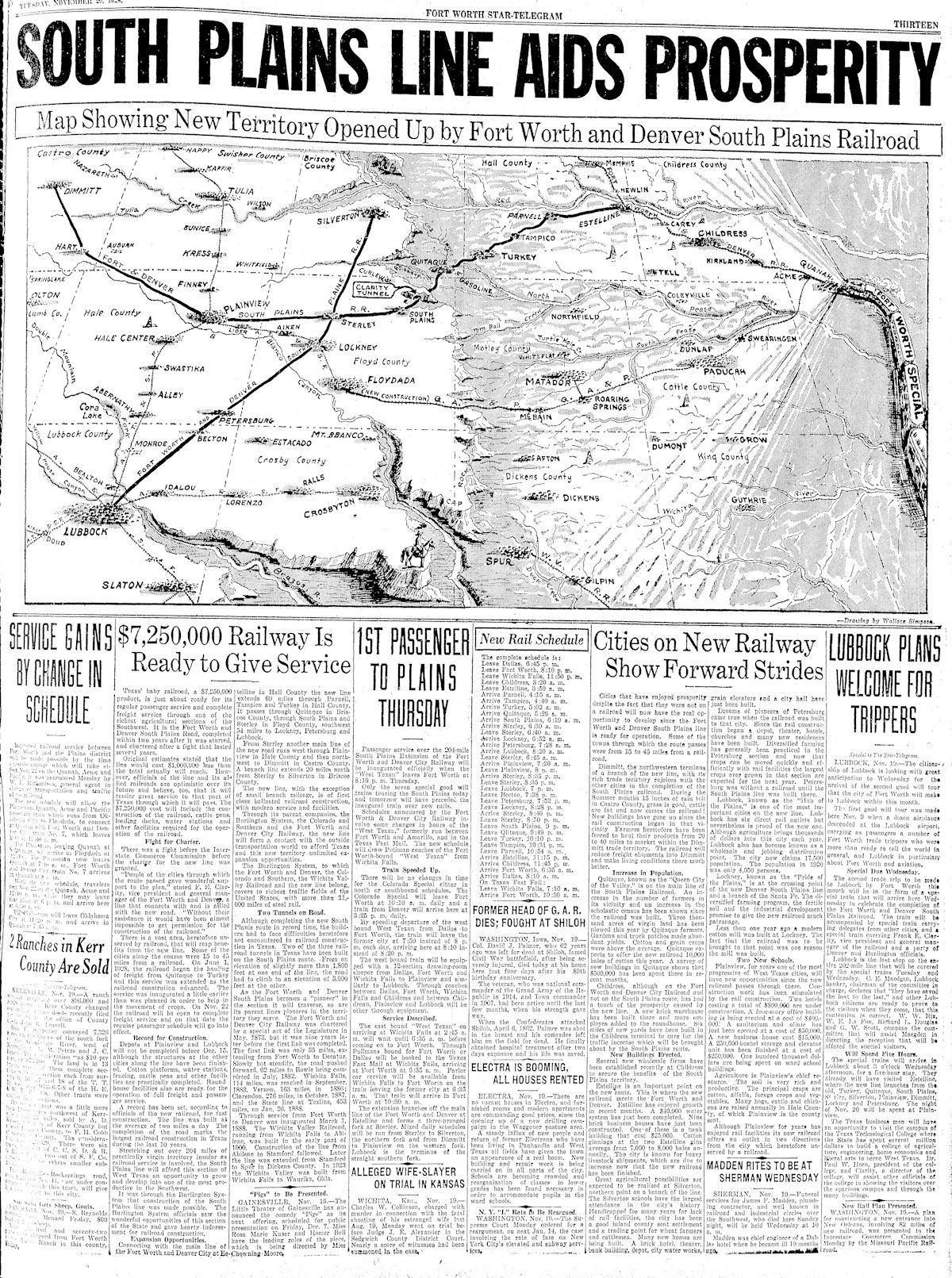

In 1928 the Fort Worth & Denver City added to its Panhandle service. The Star-Telegram trumpeted the railroad’s new South Plains lines, which stretched across a sprawling and sparsely populated area of pump jacks and jackrabbits from the FW&DC main line at Estelline to Lubbock, from Sterley to Dimmitt, and from Sterley to Silverton.

In 1928 the Fort Worth & Denver City added to its Panhandle service. The Star-Telegram trumpeted the railroad’s new South Plains lines, which stretched across a sprawling and sparsely populated area of pump jacks and jackrabbits from the FW&DC main line at Estelline to Lubbock, from Sterley to Dimmitt, and from Sterley to Silverton.

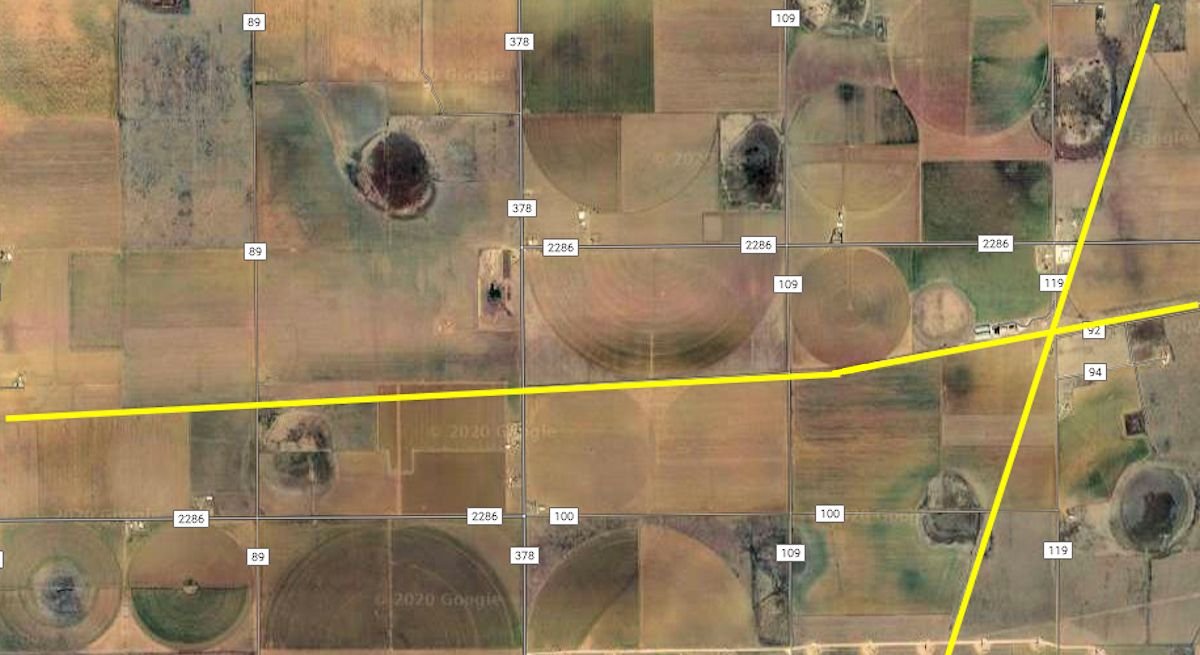

Sterley, like so many towns, was established as the FW&DC track was laid. And like so many towns born of a railroad, it was named for a railroad official, in this case W. F. Sterley, general agent of the FW&DC. The town of Sterley was twice blessed: built at the crossroads of the two Fort Worth & Denver City South Plains lines. Indeed, the town prospered for a while, having a depot, school, cotton gin, two churches.

Sterley, like so many towns, was established as the FW&DC track was laid. And like so many towns born of a railroad, it was named for a railroad official, in this case W. F. Sterley, general agent of the FW&DC. The town of Sterley was twice blessed: built at the crossroads of the two Fort Worth & Denver City South Plains lines. Indeed, the town prospered for a while, having a depot, school, cotton gin, two churches.

But as the railroad industry shrank, the trains stopped running. When the Sterley post office closed in 1969, the population of the town was ten.

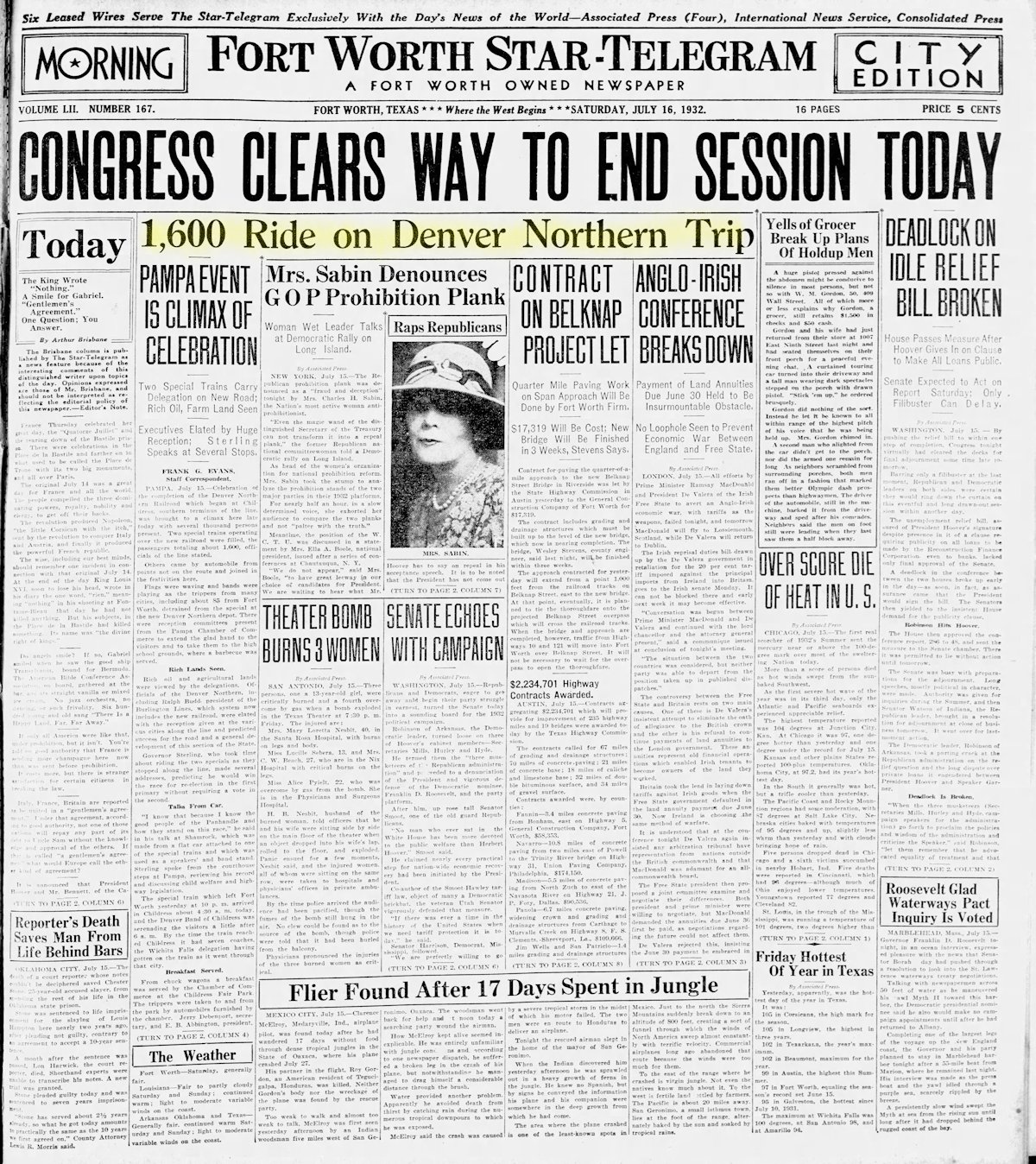

In 1932 the Denver Road added another line in the Panhandle between Childress and Pampa. To celebrate, the railroad ran excursion trains along the new route. Governor Ross Sterling rode along and made speeches.

In 1932 the Denver Road added another line in the Panhandle between Childress and Pampa. To celebrate, the railroad ran excursion trains along the new route. Governor Ross Sterling rode along and made speeches.

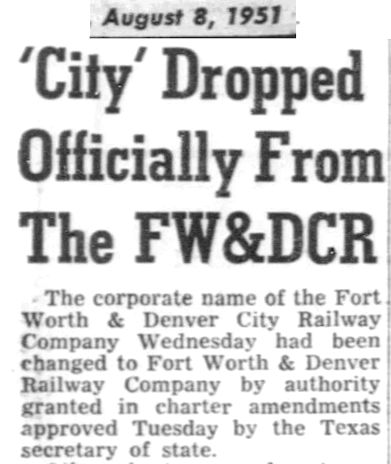

In 1951 the name of the railroad was changed to “Fort Worth & Denver” (no “City”).

In 1951 the name of the railroad was changed to “Fort Worth & Denver” (no “City”).

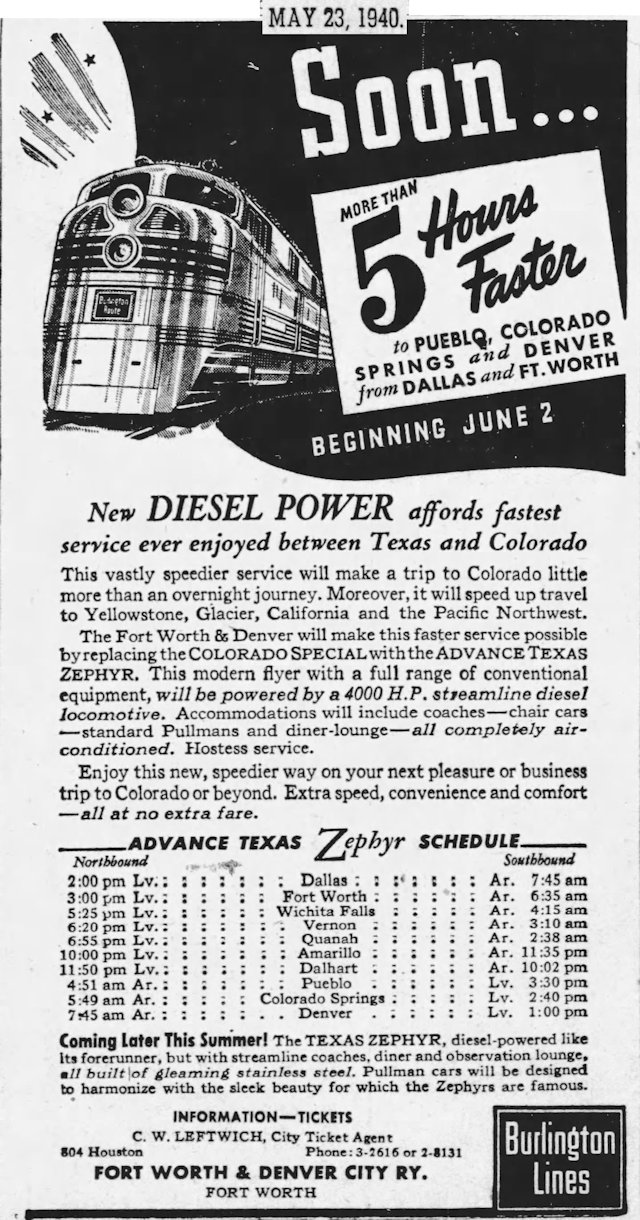

In the 1940s the Denver Road continued to switch from steam locomotives to diesel engines on trains such as the Zephyr: air-conditioned, stainless steel, four thousand horsepower. The new engines reduced the trip from Fort Worth to Denver to under seventeen hours—half the duration of 1888.

In the 1940s the Denver Road continued to switch from steam locomotives to diesel engines on trains such as the Zephyr: air-conditioned, stainless steel, four thousand horsepower. The new engines reduced the trip from Fort Worth to Denver to under seventeen hours—half the duration of 1888.

By 1959 only two steam locomotives remained on the Denver Road.

In the late 1950s the railroad industry, already facing competition from the airlines, now competed with the interstate highway system.

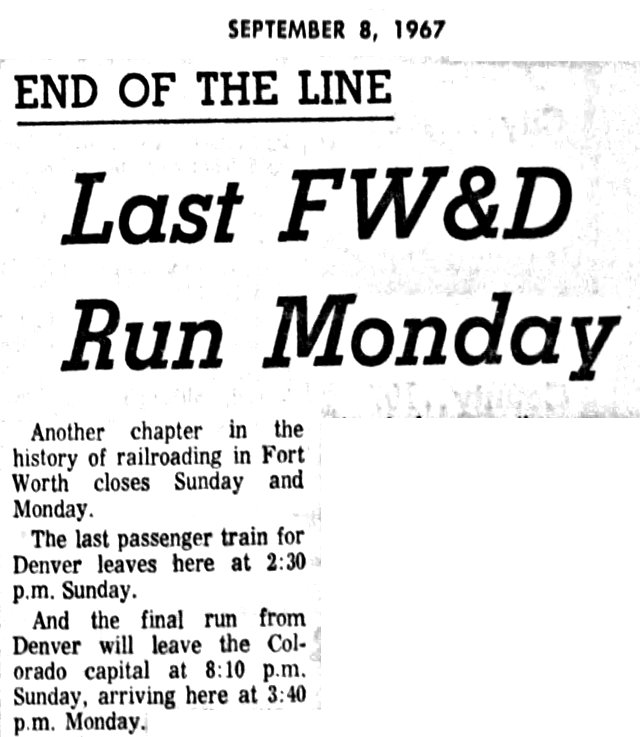

Fort Worth & Denver passenger service in Fort Worth ended in 1967 after eighty-five years. Texas & Pacific passenger service ended in 1969 after ninety-three years. That’s a combined 178 years for two railroads that overcame the double whammy of 1873.

Fort Worth & Denver passenger service in Fort Worth ended in 1967 after eighty-five years. Texas & Pacific passenger service ended in 1969 after ninety-three years. That’s a combined 178 years for two railroads that overcame the double whammy of 1873.

What remains of the Denver Road in Fort Worth today?

This Fort Worth & Denver overpass is on Northeast 28th Street.

This Fort Worth & Denver overpass is on Northeast 28th Street.

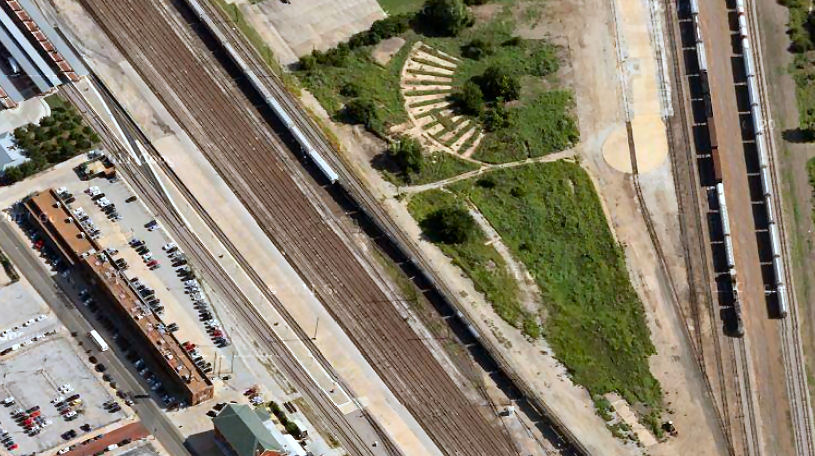

This aerial photo of the railyard just east of the Convention Center downtown shows the footprint of a roundhouse (the fan-shaped concrete pads) of the Fort Worth & Denver railroad.

This aerial photo of the railyard just east of the Convention Center downtown shows the footprint of a roundhouse (the fan-shaped concrete pads) of the Fort Worth & Denver railroad.

The roundhouse was still there in 1952, as this aerial photo shows. The roundhouse was gone by 1970.

The roundhouse was still there in 1952, as this aerial photo shows. The roundhouse was gone by 1970.

Posts About Trains and Trolleys

So enjoyed this. On that lonesome drive to Denver get off of the highway a few miles north and go through Folsom NM. Now somewhat of a ghost town. It too moved to be close to the tracks. Previously named Madison, then became Ragtown because of all of the tents they lived in to be close to the tracks. President Cleveland stepped off of that train at Ragtown with his beautiful fiancé Frances Folsom. Folks were so enamored by her they then changed the name of the town to Folsom!

Thanks, Jane.

Where could I find the primary source for the newspaper referring to Clarendon?

That clip is from the Fort Worth Gazette, online at Portal to Texas History.

Wish they would put a passenger back train on that line. It is a long drive!

Long and lonesome.

I think Sterley had a cafe which kept a 6-foot tall invisible rabbit as a pet rather than an eatery actually operated by the Fred Harvey Co. It was common back in the day to describe a railroad cafe as a “Harvey House” especially if the food was good. FW&DC did not contract with Fred Harvey.

Nice write-up, as usual!

Makes sense. I think Harvey was aligned with Santa Fe. Have made that correction. Thanks.

The line from Estelline to South Plains, including the Clarity Tunnel is now the Caprock Canyons State Trailway, a hike-and-bike trail operated by Texas Parks and Wildlife. The FW&D South Plains depot in Lubbock is now the Buddy Holly Center, featuring exhibits on the Lubbock-born rock star and anchor to the surrounding Depot District.

Thanks, Greg. An important part of history for more than just Fort Worth and Denver.