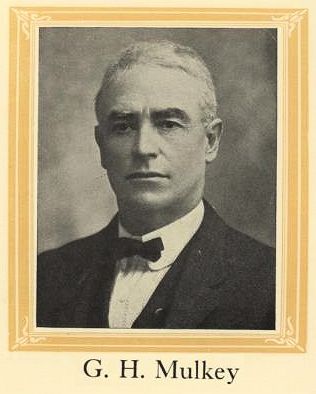

To frontier settlers, he was the mailman. To “soiled doves,” he was the top cop with a heart of gold. To children, he was the patron saint of roller skates. To schools and churches, he was a financial benefactor.

And to a generation of Fort Worth residents, he was just “Uncle George.”

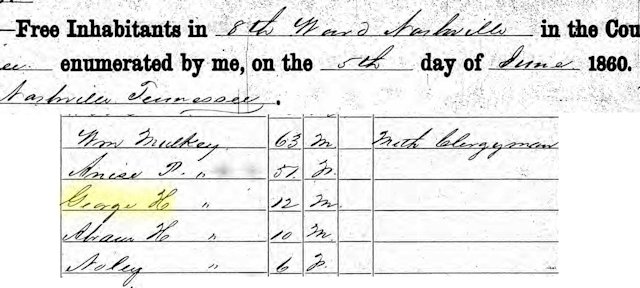

George Hill Mulkey was born in Arkansas in 1847 to Reverend William Aken and Annis Pinkerton Mulkey. Reverend Mulkey (1796-1870) was an early Methodist circuit rider. He also served as a missionary to Native Americans as the federal government relocated them from their homes to the Indian Territory.

George Hill Mulkey was born in Arkansas in 1847 to Reverend William Aken and Annis Pinkerton Mulkey. Reverend Mulkey (1796-1870) was an early Methodist circuit rider. He also served as a missionary to Native Americans as the federal government relocated them from their homes to the Indian Territory.

By 1860 the Mulkeys were living in Nashville. George, age twelve, sold newspapers on the street and saved his pennies and three-cent pieces in a piggy bank.

By 1860 the Mulkeys were living in Nashville. George, age twelve, sold newspapers on the street and saved his pennies and three-cent pieces in a piggy bank.

At the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861 Reverend Mulkey moved with his family to Waxahachie.

George Mulkey recalled: “We put all our worldly possessions in the five-spring hack [wagon] after all six of us were safely stowed away and came to Texas.”

By 1862, with so many men away fighting in the war, George, at age fourteen, got a job delivering the mail on horseback.

“I got my first job in Waxahachie carrying mail. . . . I rode from Waxahachie to Dallas and Tarrant counties and spent the night in Arlington [Johnson Station], then rode into Birdville the next day. It took me three days to make my rounds. Then I started all over again.”

The Star-Telegram later wrote: “For this jaunt Mulkey was paid $1 per day, fed his horse and himself.”

In 1863 Mulkey enlisted in the Confederate Army.

“When I was fifteen I was in the Confederate Army in Texas. Our job was to go through the country and confiscate meat for the army. We would go through a man’s herd and cull out the beeves that were over four years old and drive off the steers on the hoof for the army. No, we were not popular, and oftentimes the cattlemen took a shot at us, and we had a pretty tough time in general. It was hard, too, because we did not want to do it in the first place.”

After the war Mulkey, at age eighteen, became a freighter. His route was from the terminus of the Houston & Texas Central railroad in Houston to Fort Worth, Dallas, and Waxahachie. He slept in his wagon or on the ground and ate what he “toted” with him.

In 1872 he moved to Fort Worth. His first job here paid him a dollar a day and board.

“I could get meat to eat by working for board too, and we didn’t always have it at home,” he recalled. “I worked for a builder named Frazier making bricks by hand. I guess I’ve made some of the bricks in these oldest houses in Fort Worth. At odd times my brothers and I used to plait wheat into strands and make straw hats. We were very frugal in those days.”

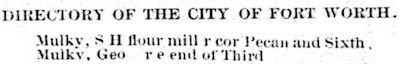

Mulkey and his older brother, Stephen Holland Mulkey, later operated a grist mill on the east side of town.

Mulkey and his older brother, Stephen Holland Mulkey, later operated a grist mill on the east side of town.

The Star-Telegram later wrote: “It was a toll mill, and as he ground the corn for farmers, Mulkey most often took his pay in corn. That mill was on the creek that used to run where the Farmers and Mechanics Bank skyscraper now stands.”

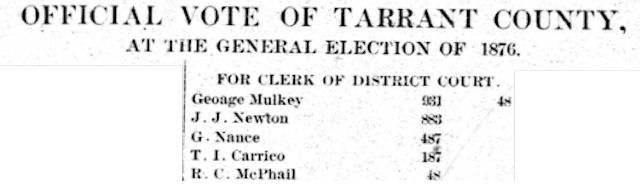

In 1876 Mulkey entered politics. After campaigning on foot through much of the county, he was elected district clerk.

In 1876 Mulkey entered politics. After campaigning on foot through much of the county, he was elected district clerk.

He soon traded politics for banking, joining City National Bank and then Traders’ National Bank.

Meanwhile Mulkey served as one of the early chiefs of Fort Worth’s volunteer fire department in the 1870s and served three terms as city alderman from the First and Sixth wards in the 1880s and 1890s.

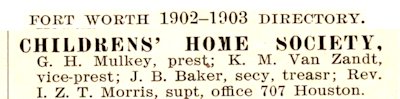

Mulkey also was president of the Texas Children’s Home and Aid Society, which had evolved out of Reverend Isaac Zachary Taylor Morris’s charity work with children of the orphan trains.

Mulkey also was president of the Texas Children’s Home and Aid Society, which had evolved out of Reverend Isaac Zachary Taylor Morris’s charity work with children of the orphan trains.

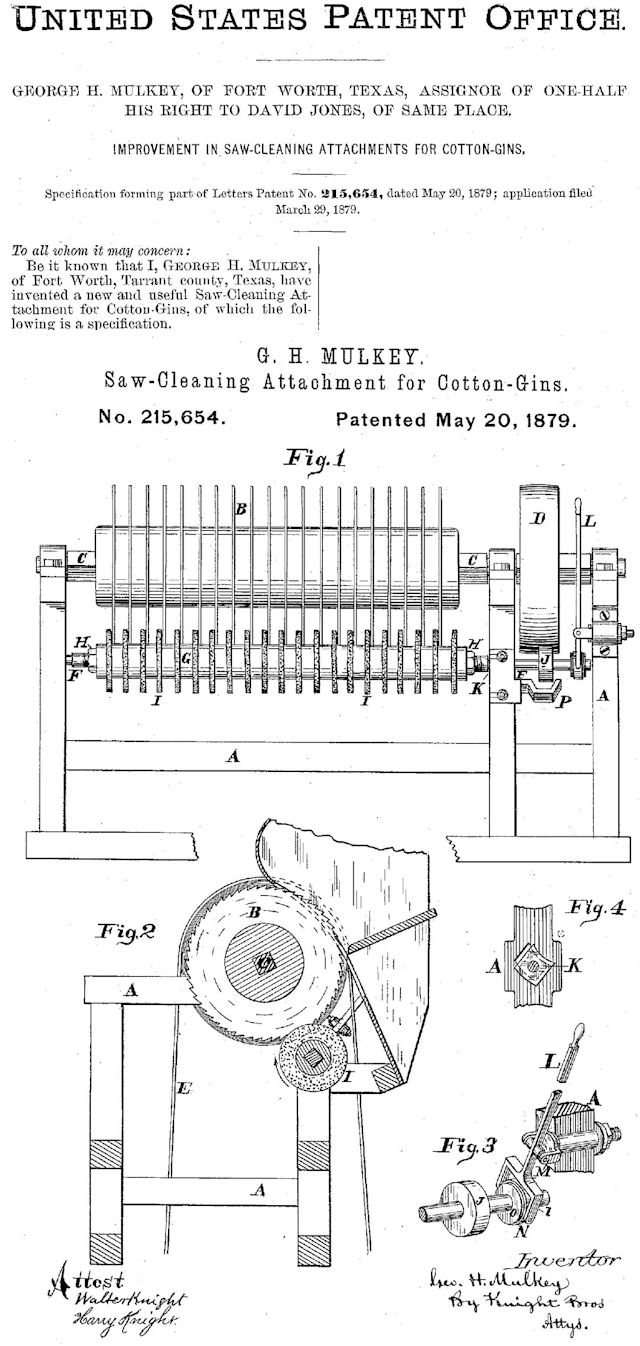

Mulkey found time even to do a little inventing: a saw-cleaning attachment for cotton gins.

Mulkey found time even to do a little inventing: a saw-cleaning attachment for cotton gins.

George’s father William and George’s brother Abe were Methodist preachers. Dedication to Methodism was deep seated in George also. In the early days Fort Worth’s Methodists had no church building. They worshiped in the courthouse, in lodge halls, etc., served by circuit riders such as John Wesley Chalk. But in 1873 local Methodists bought a lot at the corner of Jones and 4th streets and the next year built a one-room wooden building for Fourth Street Methodist Church. J. C. Terrell, William Jesse Boaz, and George Mulkey’s brother Stephen were among those who each contributed $100 ($2,000 today). George Mulkey did not have $100 but donated his labor—at the planing mill where he worked he planed and tongue-and-grooved the lumber for the building.

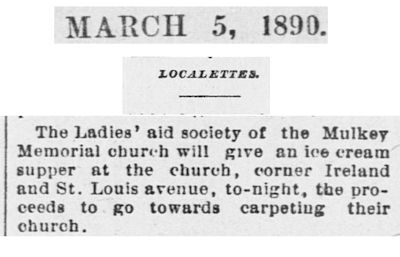

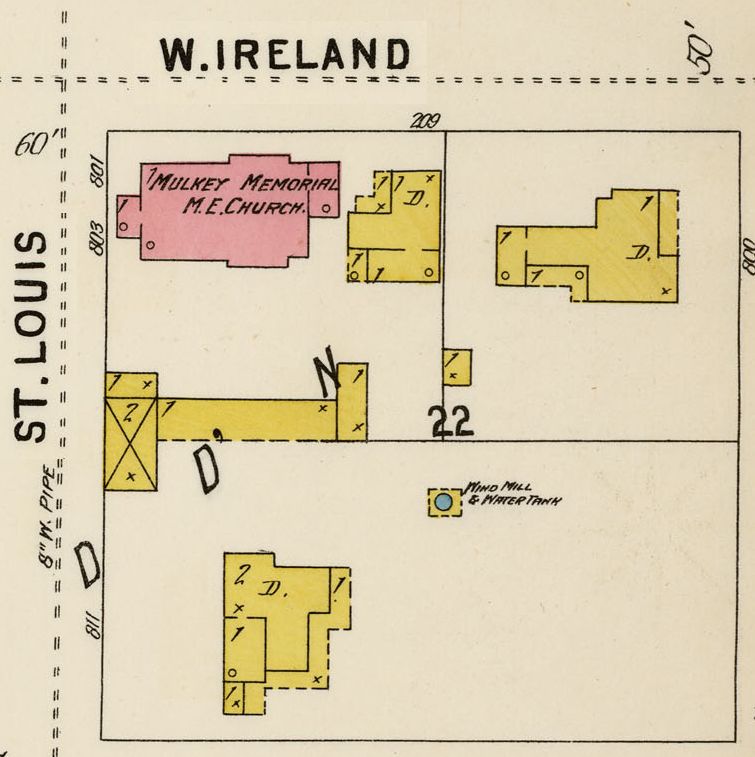

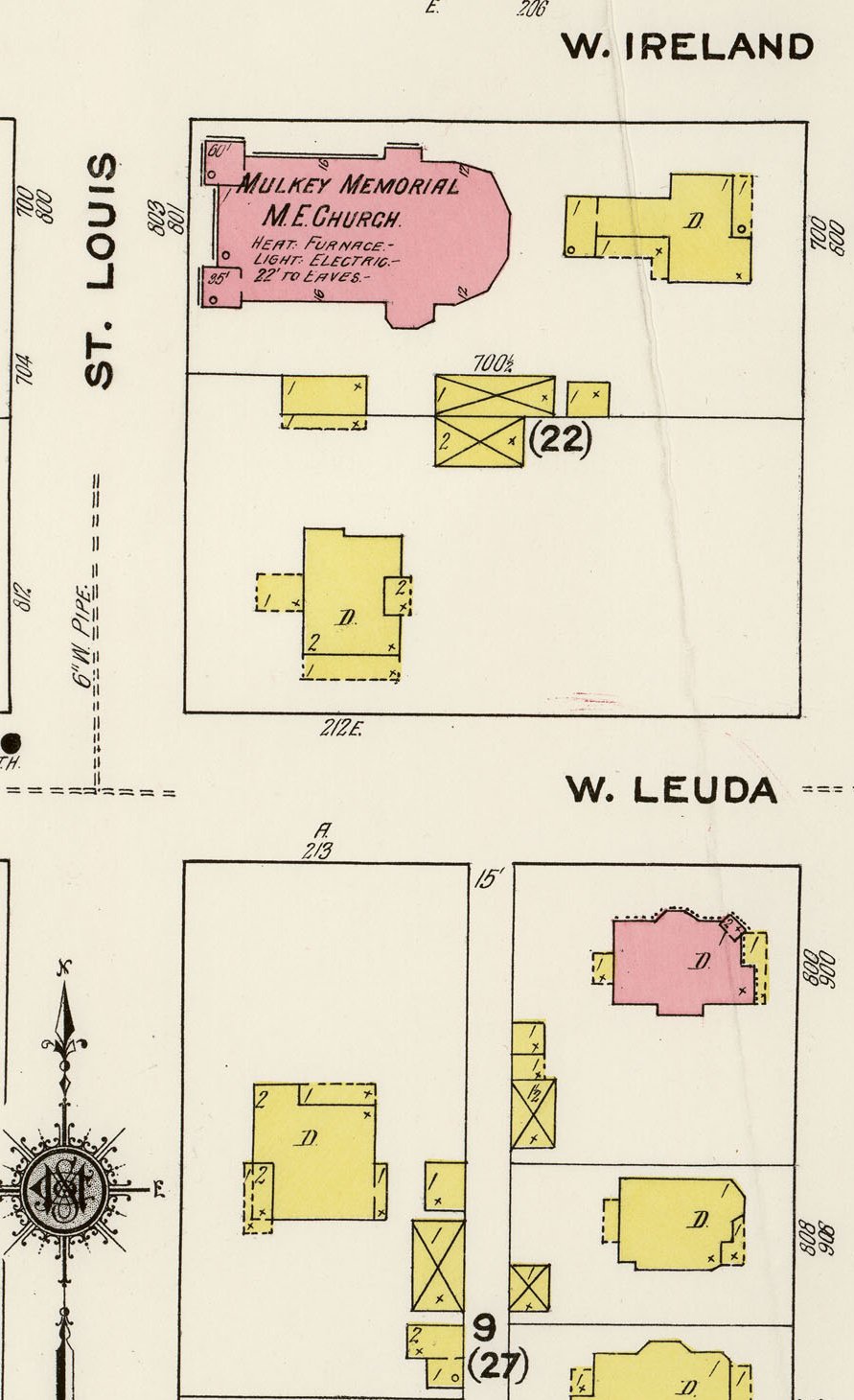

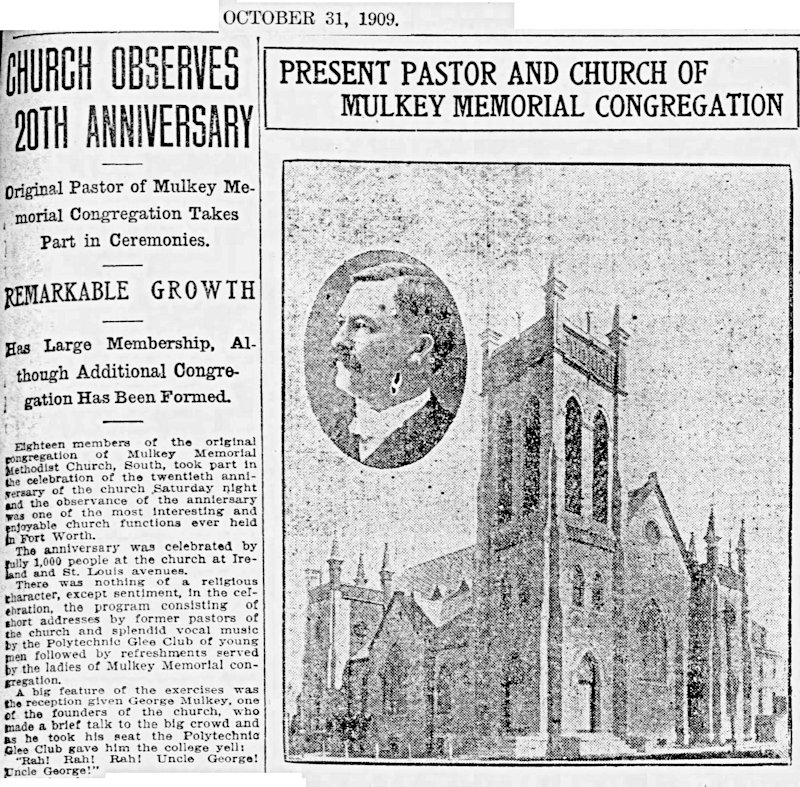

George’s father had died in 1870, his mother in 1868. By 1889 George had prospered. To honor his parents he built a church and named it “Mulkey Memorial Methodist Church.” The church was located at the corner of St. Louis and Ireland (Cannon today) streets on the near South Side. H. A. Boaz was one of the early pastors of the church.

George’s father had died in 1870, his mother in 1868. By 1889 George had prospered. To honor his parents he built a church and named it “Mulkey Memorial Methodist Church.” The church was located at the corner of St. Louis and Ireland (Cannon today) streets on the near South Side. H. A. Boaz was one of the early pastors of the church.

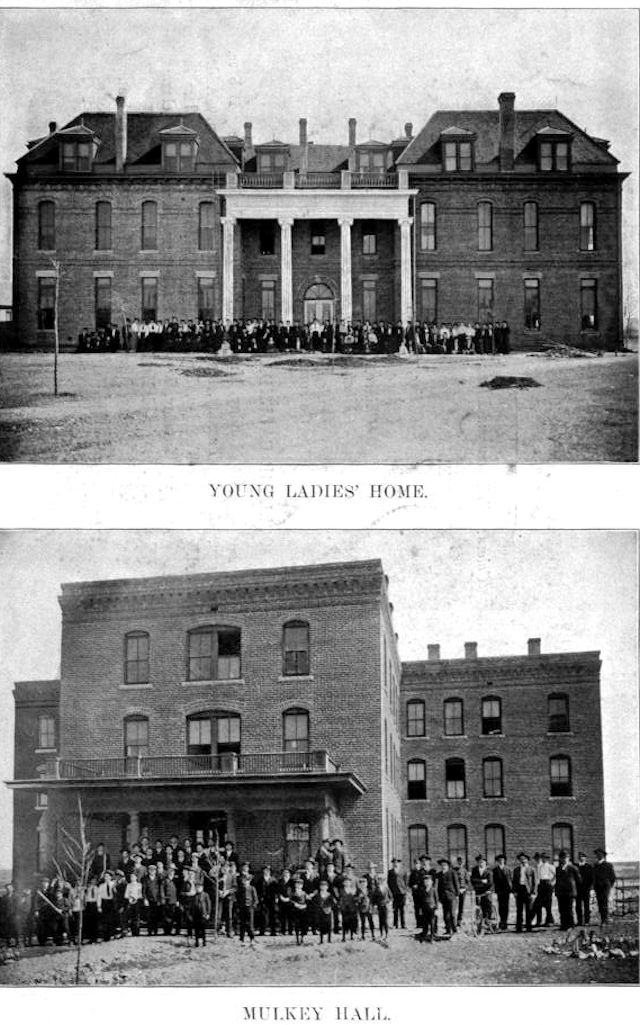

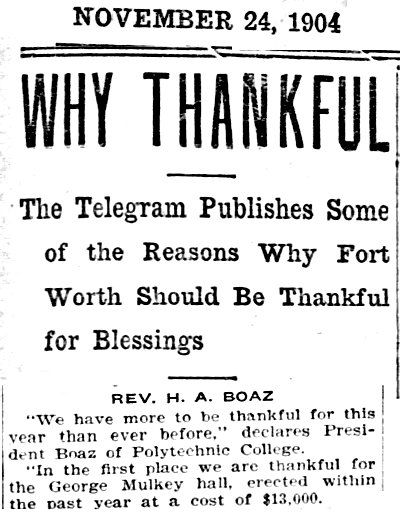

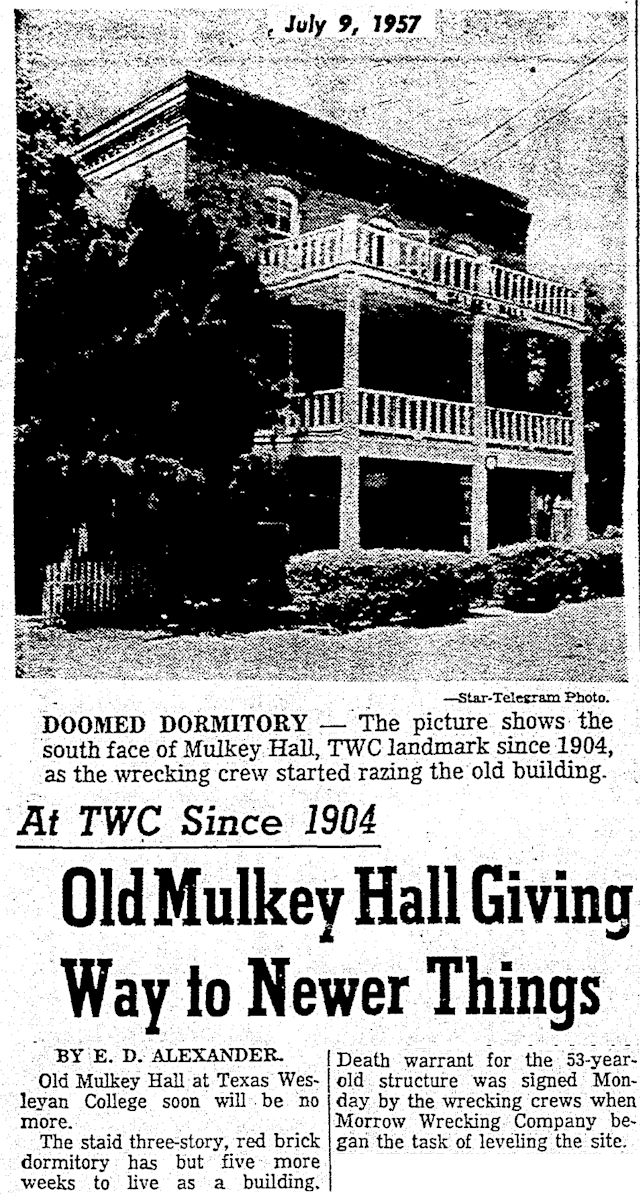

George Mulkey also was one of the biggest financial supporters of another Methodist institution: Polytechnic College. In 1904 he donated $13,000 ($375,000 today) to build Mulkey Hall dormitory. By 1904 H. A. Boaz was president of Polytechnic College.

George Mulkey also was one of the biggest financial supporters of another Methodist institution: Polytechnic College. In 1904 he donated $13,000 ($375,000 today) to build Mulkey Hall dormitory. By 1904 H. A. Boaz was president of Polytechnic College.

The year 1907 brought two milestones for George Mulkey.

The year 1907 brought two milestones for George Mulkey.

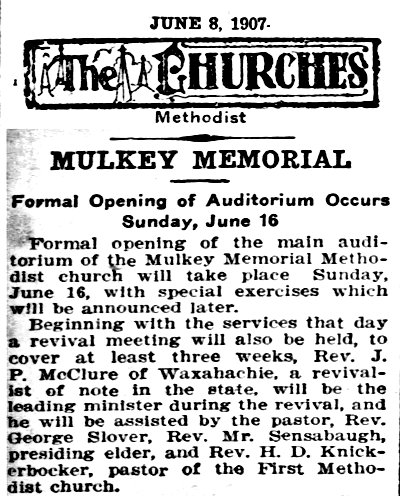

First, he helped finance a new building for Mulkey Memorial Methodist Church, whose auditorium was formally opened on June 16. The new building was built on the site of the old one. George Mulkey’s home at 213 West Leuda Street was directly behind the church.

(The Telegram reported that a revival would be held in the new building. Among ministers leading the revival would be Reverend Oscar Sensabaugh, whose daughter Leona in 1910 would marry a fellow Polytechnic College graduate who in 1915 would plant a time bomb that damaged the U.S. Capitol building, shoot financier J. P. Morgan Jr. in Morgan’s mansion, and plant a time bomb on a ship carrying munitions to England.)

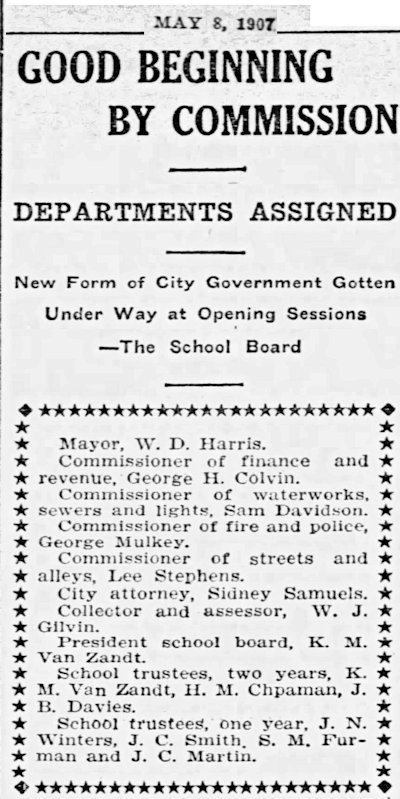

Second, in 1907 George Mulkey re-entered politics. He was elected a city commissioner after the city adopted the city commission form of government. W. D. Harris was elected mayor and assigned to each of the four commissioners a city department to govern: finance and revenue; waterworks, sewers, and lights; streets and alleys; and fire and police. Mulkey, who had wanted to be commissioner of streets and alleys, was appointed the city’s first commissioner of fire and police.

Second, in 1907 George Mulkey re-entered politics. He was elected a city commissioner after the city adopted the city commission form of government. W. D. Harris was elected mayor and assigned to each of the four commissioners a city department to govern: finance and revenue; waterworks, sewers, and lights; streets and alleys; and fire and police. Mulkey, who had wanted to be commissioner of streets and alleys, was appointed the city’s first commissioner of fire and police.

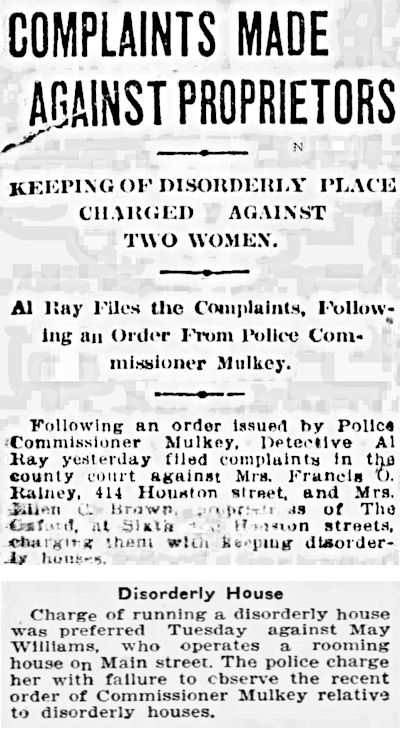

Among Mulkey’s priorities as commissioner of the police department was eliminating vice, especially prostitution and especially in Hell’s Half Acre, the redlight district in the south end of downtown.

Among Mulkey’s priorities as commissioner of the police department was eliminating vice, especially prostitution and especially in Hell’s Half Acre, the redlight district in the south end of downtown.

Mulkey’s plan to control vice in Fort Worth included two strategies that were controversial.

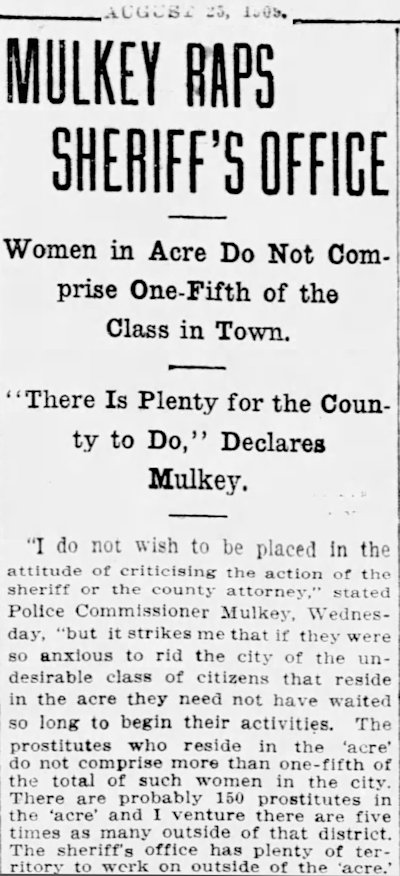

First, unlike some reformers, he did not think that forcing prostitutes, gamblers, etc. to move out of the Acre would be effective. Mulkey feared that scattering such lawbreakers throughout the city would make them more difficult to find and arrest.

Second, Mulkey felt that the county government, via the county attorney and sheriff, should share the responsibility for controlling vice in Fort Worth, including in the Acre.

Second, Mulkey felt that the county government, via the county attorney and sheriff, should share the responsibility for controlling vice in Fort Worth, including in the Acre.

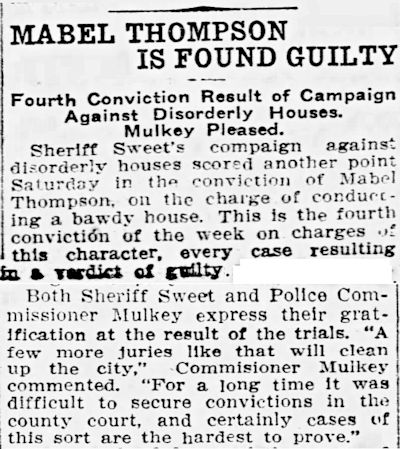

Thus, Mulkey was pleased when four women arrested in Fort Worth by Sheriff Oliver Sweet were convicted of operating “disorderly houses.”

Thus, Mulkey was pleased when four women arrested in Fort Worth by Sheriff Oliver Sweet were convicted of operating “disorderly houses.”

Two of the convicted women plied their trade in the Acre.

Mulkey vowed to eliminate vice, but at the end of Mulkey’s long arm of the law was a kid glove. The Star-Telegram later wrote: “When Mulkey was first fire and police commissioner of Fort Worth under the commission form of goverment he had under him at that time officers who often found it necessary to treat women rough when making arrests. But even when Mulkey caused raids to be made in old Hell’s Half Acre, he insisted that the women of the underworld be gently treated.”

Another anecdote demonstrates Mulkey’s compassion: He was forced to suspend a police officer for ten days because of drunkenness. The officer, with tears in his eyes, pleaded with Mulkey, saying that missing ten days of pay would cause him to miss a mortgage payment and lose his home.

Mulkey stood firm.

“I will not change the decision I have made concerning you,” Mulkey said. He then opened his wallet and handed the officer $40.

“Go pay your house note and sober up and come back in ten days.”

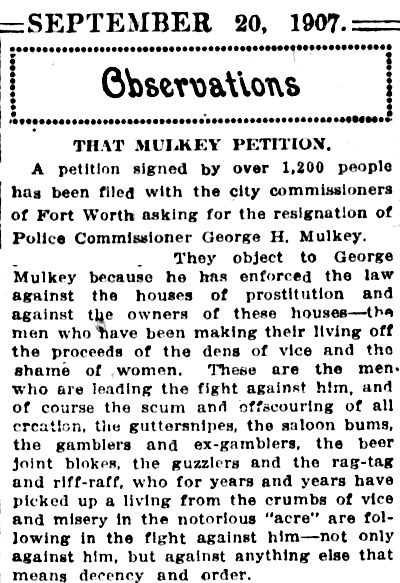

But other residents saw Mulkey as anything but compassionate. He had not been on the job long before a petition—signed by twelve hundred residents—was filed with the city commission asking for his recall.

But other residents saw Mulkey as anything but compassionate. He had not been on the job long before a petition—signed by twelve hundred residents—was filed with the city commission asking for his recall.

The Telegram wrote of the leaders of the recall effort: “They object to George Mulkey because he has enforced the law against the houses of prostitution and against the owners of these houses—the men who have been making their living off the proceeds of the dens of vice and the shame of women. These are the men who are leading the fight against him, and of course the scum and offscouring of all creation, the guttersnipes, the saloon bums, the gamblers and ex-gamblers, the beer joint blokes, the guzzlers and the rag-tag and riff-raff.”

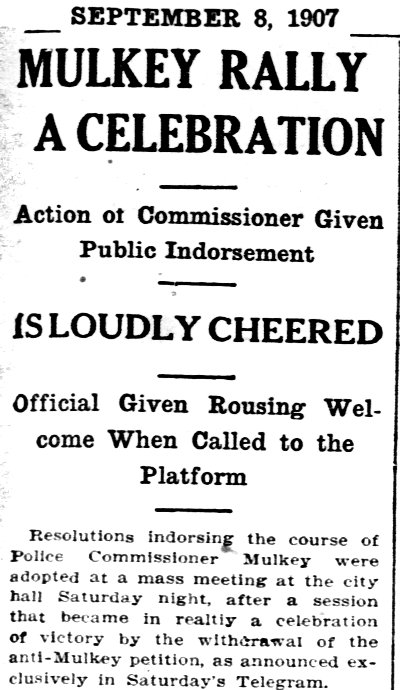

The rag-tag and riff-raff soon dropped their petition, and Mulkey went about his business.

The rag-tag and riff-raff soon dropped their petition, and Mulkey went about his business.

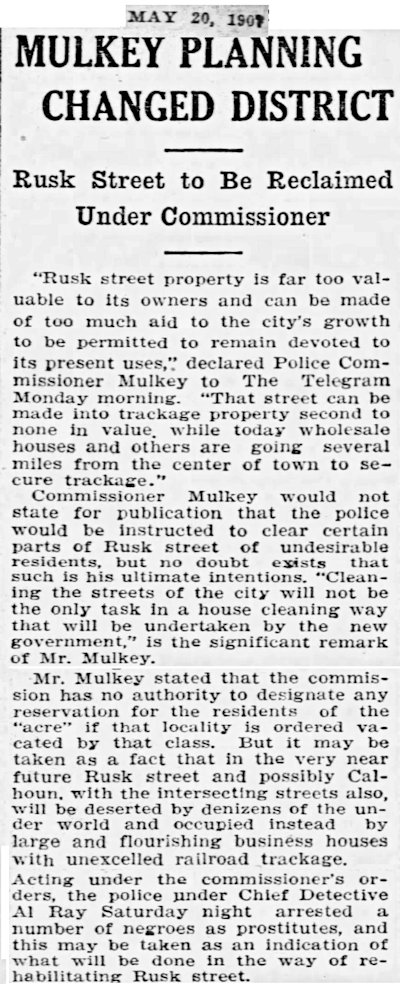

Mulkey did not think it wise to scatter the lawbreakers of the Acre, but he did think that Rusk Street—the dark heart of the Acre—should be cleaned up and provided with railroad trackage to benefit the street’s legitimate businesspeople.

Mulkey did not think it wise to scatter the lawbreakers of the Acre, but he did think that Rusk Street—the dark heart of the Acre—should be cleaned up and provided with railroad trackage to benefit the street’s legitimate businesspeople.

(But change was slow to come. In 1909 those legitimate businesspeople along Rusk Street answered Shakespeare’s question “What’s in a name?” with one word: “stigma.” They demanded that their street be renamed so that their addresses would not be associated with vice. The street was renamed “Commerce.”)

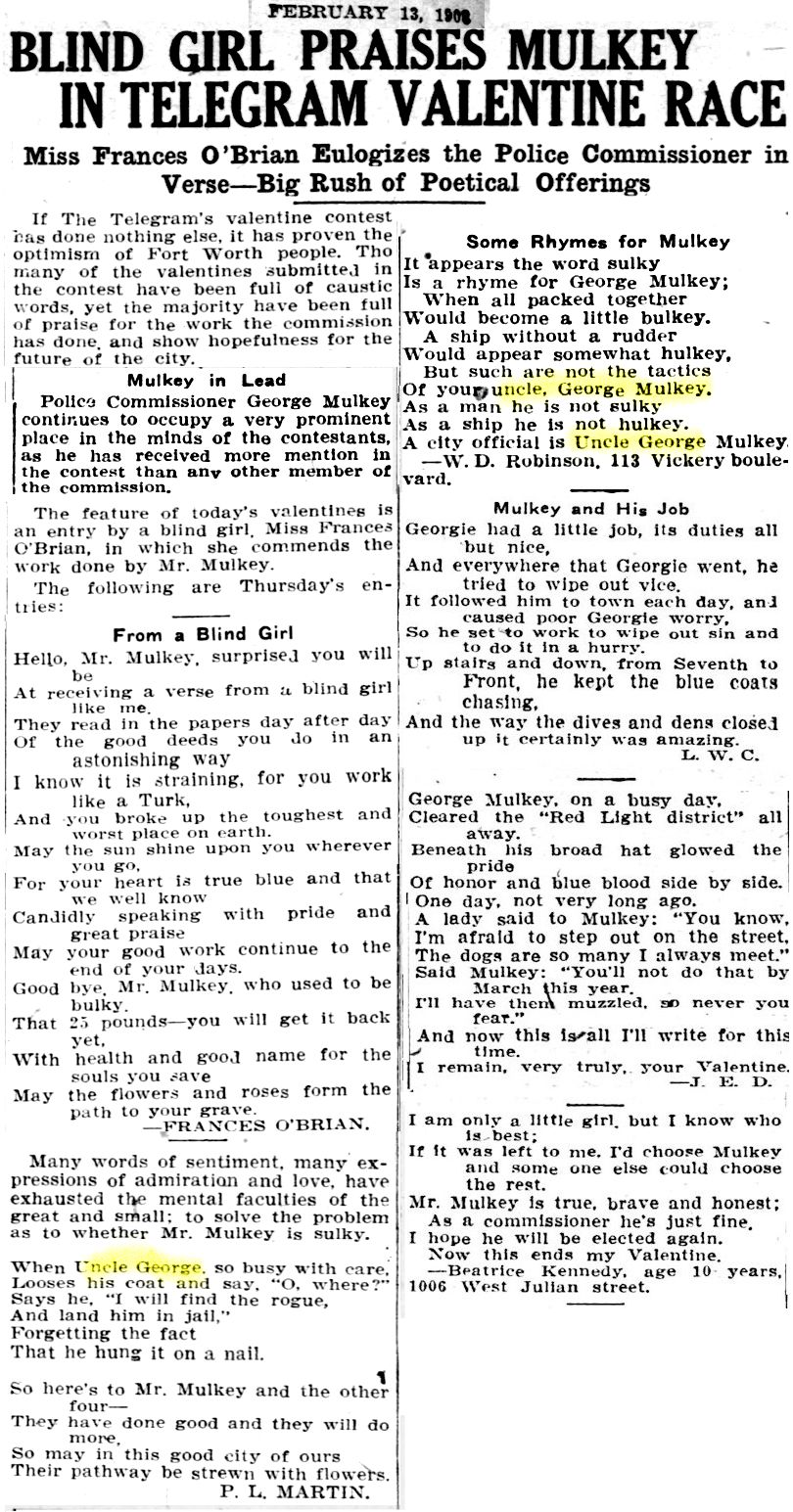

In 1908 the Telegram conducted a poetry contest, the subject being the city commission, which was ending its first year of governance. Most of the poems—some written by children—were about Mulkey, praising his campaigns to clean up the Acre and enforce laws against vagrants and stray dogs.

In 1908 the Telegram conducted a poetry contest, the subject being the city commission, which was ending its first year of governance. Most of the poems—some written by children—were about Mulkey, praising his campaigns to clean up the Acre and enforce laws against vagrants and stray dogs.

Note that two poems referred to Mulkey as “Uncle George.”

White of hair, gentle of nature, and quick to smile, avuncular Mulkey was known to Fort Worth residents as “Uncle George.”

White of hair, gentle of nature, and quick to smile, avuncular Mulkey was known to Fort Worth residents as “Uncle George.”

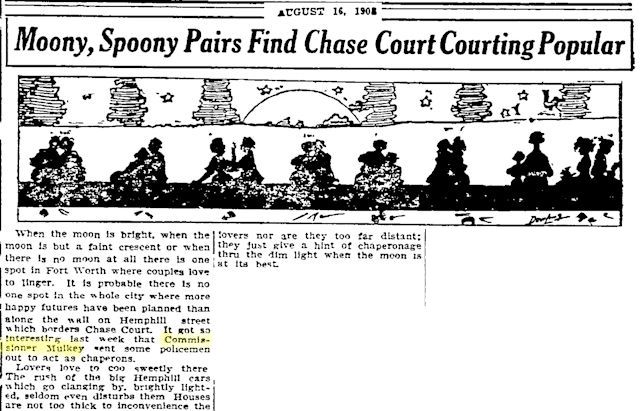

In 1908 the near South Side was still sparsely populated, and Hemphill Street’s lack of illumination was inviting to lovebirds, who at night perched on the wall surrounding the new enclave of Chase Court. So popular was the wall with bill-and-cooers that Mulkey dispatched officers to act as “chaperones.”

In 1909 the congregation of the second church that Mulkey had built to honor his parents celebrated the church’s twentieth anniversary. After Mulkey addressed the audience, the Polytechnic Glee Club chanted, “Rah! Rah! Rah! Uncle George! Uncle George!”

In 1909 the congregation of the second church that Mulkey had built to honor his parents celebrated the church’s twentieth anniversary. After Mulkey addressed the audience, the Polytechnic Glee Club chanted, “Rah! Rah! Rah! Uncle George! Uncle George!”

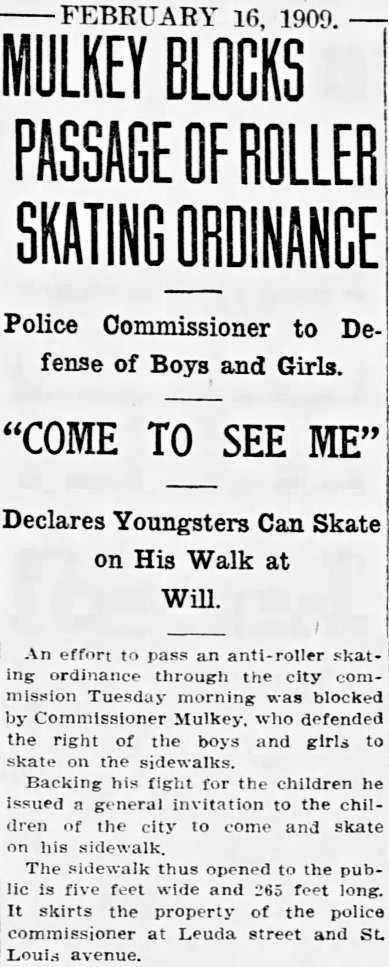

Also in 1909 Uncle George earned more praise, especially from the too-young-to-vote set, when he blocked passage of a proposed ordinance that would have prohibited roller skating on streets and sidewalks. In fact, he invited Fort Worth children to skate on his sidewalks.

Also in 1909 Uncle George earned more praise, especially from the too-young-to-vote set, when he blocked passage of a proposed ordinance that would have prohibited roller skating on streets and sidewalks. In fact, he invited Fort Worth children to skate on his sidewalks.

Mulkey lived on a corner with sidewalks along two sides of his lot—a total of 265 feet. Soon his sidewalk was crowded from edge to edge with roller skaters. Those children who could not be there in person telephoned their gratitude to Uncle George.

Today Uncle George’s house at the corner of St. Louis and West Leuda streets is gone, but all that smooth-rollin’ sidewalk survives.

Mulkey served four years as fire and police commissioner and retired.

But he remained active.

“More people die from too little work than from too much,” he said.

He bought and sold real estate and continued his long association with Traders’ National Bank, serving as vice president.

George Mulkey was a never-too-later. He had become fire and police commissioner at age sixty. And in 1922, at age seventy-five, he became a farmer, buying a farm near Joshua. His wife told the Star-Telegram: “He catches the 6:30 [street]car every morning so he can work it [the farm].”

Because the Mulkeys lived on West Leuda Street just two blocks from Main Street, Mulkey each morning probably walked to Main, where he boarded a streetcar headed to downtown, where he boarded a Dallas interurban car and rode east to the junction of the Dallas interurban and Cleburne interurban, where, switching lines again, he rode his third streetcar of the morning south to Joshua. Now that was a man determined to sow some seeds!

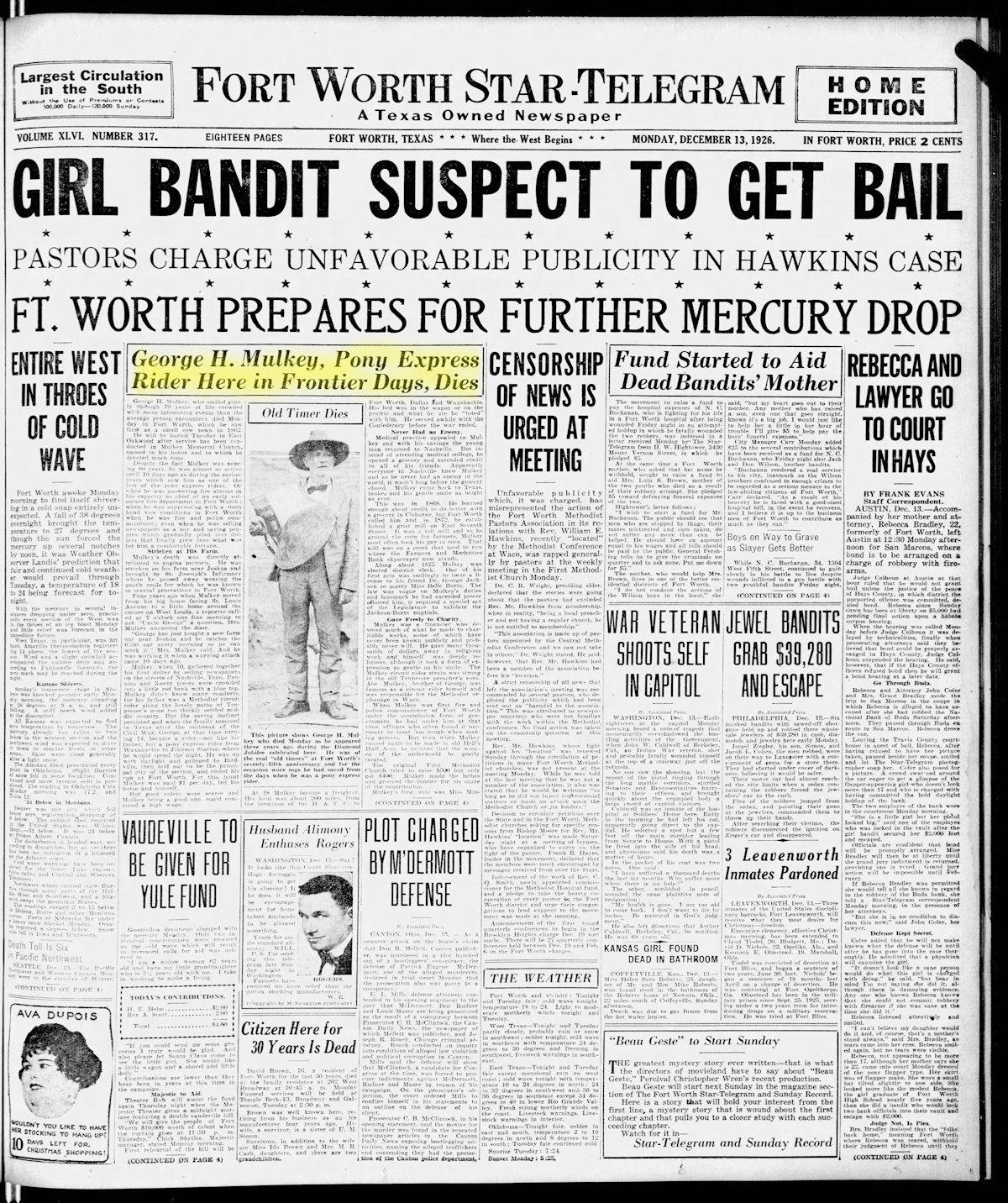

But in 1926, at age seventy-nine, Mulkey was working at his farm when he was stricken by angina pectoris. He died at St. Joseph’s Infirmary.

But in 1926, at age seventy-nine, Mulkey was working at his farm when he was stricken by angina pectoris. He died at St. Joseph’s Infirmary.

The headline refers to him as having been a “Pony Express rider,” but technically the Pony Express was a long-distance mail service between Missouri and California. Mulkey had been a short-distance mail rider under contract to George Franklin Marchbanks of Waxahachie.

Mulkey’s funeral was held in the second church he built and named for his parents.

George Hill Mulkey is buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

George Hill Mulkey is buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

The rest of the story:

The rest of the story:

In 1940 Mulkey Memorial Methodist Chutch merged with Broadway Methodist Church to become “St. Mark United Methodist Church.” In 1959 St. Mark moved to 6250 South Freeway. The church changed its name to “Christ United Methodist Church” about 1990 and in 1993 moved to Sycamore School Road. The site of Mulkey Memorial Methodist Church is now occupied by a nursing home.

Mulkey Hall was demolished in 1957.