During the second half of the nineteenth century railroads built towns just as surely as did masons and carpenters. Railroads provided a town with jobs, provided it with immigrants, and provided it with a means to ship and receive goods, all of which benefited existing business and encouraged new business. Railroads were such an economic boon that sometimes the residents of an existing town relocated their town to place it in the path of a planned railroad track that otherwise would have bypassed their town. Many other towns in Texas sprang up along railroad tracks as tracks were laid and as land along the tracks was sold for city lots. Other towns paid railroads millions of dollars to lay track to them.

Fort Worth first tried to lure a railroad to town in 1858 when citizens at a mass meeting, led by E. M. Daggett and J. C. Terrell, wrote resolutions urging the Houston & Texas Central railroad to lay track to Fort Worth. That didn’t happen. At least not right away.

But fast-forward to 1872. On a hot afternoon in July business was slow in Khleber Miller Van Zandt’s general store on the courthouse square. In his biography Force Without Fanfare Van Zandt writes that he was napping at the counter when a townsman came in and told him who had just arrived in town (by horse, of course): James W. Throckmorton, governor of Texas, and Colonel Tom Scott, president of the Texas & Pacific railroad.

Van Zandt hurried to meet the two dignitaries at their hotel and invited them back to his store to talk a little city-building.

And so it came to pass that Fort Worth’s future was forged in the afternoon heat of that humble general store.

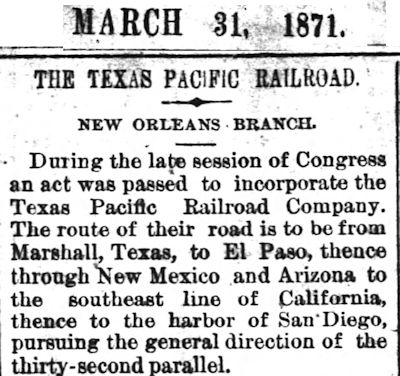

The T&P was laying track westward from Longview—to the Pacific Ocean.

The T&P was laying track westward from Longview—to the Pacific Ocean.

Van Zandt asked Scott what it would take to get the T&P to lay track through Fort Worth on its way west.

Scott said, “I want 320 acres of land south of town [for a depot and railyard]. . . . In consideration of this, I will proceed as rapidly as possible to build the Texas and Pacific Railroad to your town.”

By nightfall Van Zandt, Daggett, T. J. Jennings, and H. G. Hendricks had drawn up a contract.

Van Zandt and Daggett donated a large part of the land.

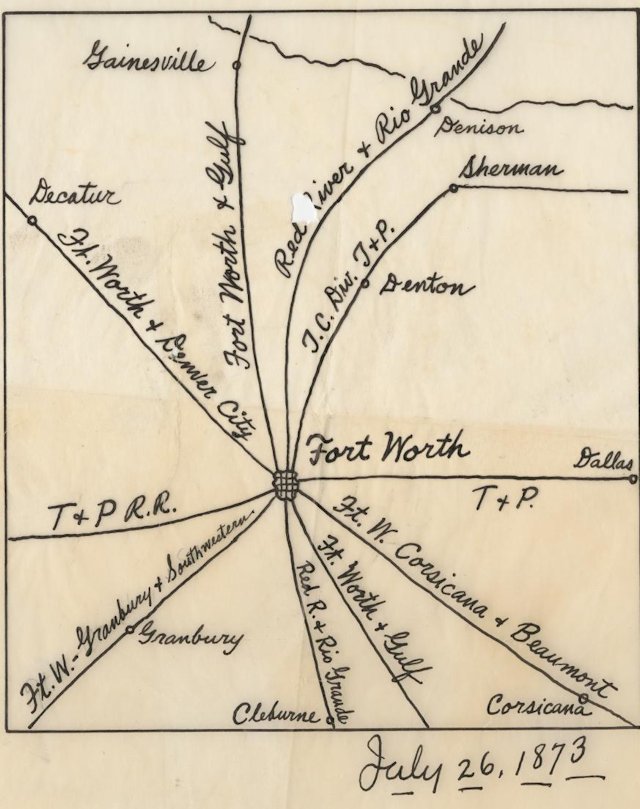

Van Zandt, Daggett, and other civic leaders were confident that the T&P would be just the start for Fort Worth. In fact, in July 1873 B. B. Paddock, editor of the Fort Worth Democrat and the town’s foremost “I think we can, I think we can” cheerleader, drew his ambitious “tarantula map” predicting that Fort Worth would one day be a railroad center. (The map represented Paddock’s vision of the future. Some of the railroad companies on that map either never were established or never served Fort Worth.) (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

Van Zandt, Daggett, and other civic leaders were confident that the T&P would be just the start for Fort Worth. In fact, in July 1873 B. B. Paddock, editor of the Fort Worth Democrat and the town’s foremost “I think we can, I think we can” cheerleader, drew his ambitious “tarantula map” predicting that Fort Worth would one day be a railroad center. (The map represented Paddock’s vision of the future. Some of the railroad companies on that map either never were established or never served Fort Worth.) (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

One month after Paddock drew his map, the T&P reached Dallas. For Fort Worth the future was just thirty miles away.

But the national economic panic of that year stopped the T&P dead in its tracks at Dallas.

However, in 1874 the T&P extended its track westward—six whole miles to Eagle Ford.

And stopped again.

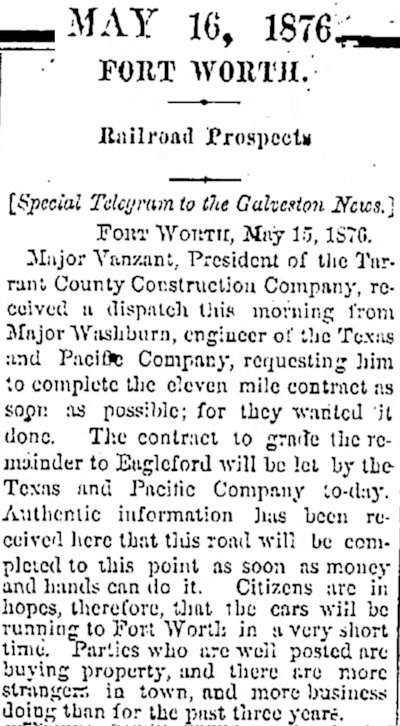

Fort Worth fretfully drummed its fingers for two more years. In 1876, with the Texas & Pacific tracks still stalled at Eagle Ford, Van Zandt pleaded with T&P officials to resume laying track to Fort Worth. He was told that the company had money to buy rails but did not have money to grade the road bed.

So, Van Zandt and other civic leaders formed the Tarrant County Construction Company, which raised $25,000 ($600,000 today) by subscription to pay for grading. Van Zandt was president of the company and negotiated a contract with a grading company.

Thus began a race-against-time drama worthy of a Hollywood movie as Fort Worth worked to beat a deadline imposed by the state legislature for completion of the track.

On July 19, 1876 came one of the seminal events in Fort Worth history. Paddock’s tarantula finally got its first leg. And yet the great event, which today would merit a special edition of the local newspaper, in 1876 received only one column of type—on page 4. Ah, but that column of type was steeped in euphoria: “quick, strong and vigorous,” “light, buoyant and hopeful,” “joy,” “gladdened,” “joy and gladness,” “mighty bulwark of strength,” “clear, bright sunlight of prosperity,” “the greatness, strength, prosperity, wealth and power is manifested,” etc.

On July 19, 1876 came one of the seminal events in Fort Worth history. Paddock’s tarantula finally got its first leg. And yet the great event, which today would merit a special edition of the local newspaper, in 1876 received only one column of type—on page 4. Ah, but that column of type was steeped in euphoria: “quick, strong and vigorous,” “light, buoyant and hopeful,” “joy,” “gladdened,” “joy and gladness,” “mighty bulwark of strength,” “clear, bright sunlight of prosperity,” “the greatness, strength, prosperity, wealth and power is manifested,” etc.

(A more-detailed account of the race to bring the Texas & Pacific railroad to town can be read here.)

And guess what? After reaching Fort Worth, the T&P stopped laying track.

Again.

But Fort Worth didn’t complain. Because for the next four years Fort Worth was the western terminus on the line. Being the terminus town brought economic benefits.

The population of Fort Worth in 1870 was 500. In 1880, after four years with a railroad, the population was 6,663.

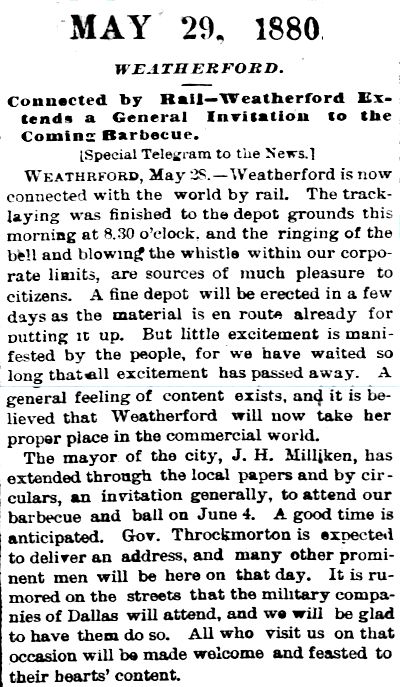

But in 1880 the track was extended to Weatherford as the Texas & Pacific began laying track westward to El Paso to meet the Southern Pacific railroad, which was laying track eastward to form America’s second transcontinental line.

Fort Worth was conflicted about the westward extension. Yes, the extension gave Fort Worth’s tarantula a second leg, but it also ended the economic benefits of being the terminus town.

Fort Worth’s civic leaders were determined to compensate for the loss of terminus status by luring more railroads. The Santa Fe railroad had laid track from Galveston north to Temple, and the Missouri Pacific (Katy) railroad had laid track south to Denison, Van Zandt writes in his biography. Van Zandt, John Peter Smith, Walter Huffman, and James Jones Jarvis calculated that if they could lure the Santa Fe to town, the Missouri Pacific would follow in order to connect with the Santa Fe track and thus gain a route to the gulf coast. Fort Worth, now just a stop on T&P’s east-west line, with a north-south track could become a railroad crossroads. The four men decided that Van Zandt would approach the Santa Fe company because he had two friends on the board of directors.

The Santa Fe company told Van Zandt that track would be extended north to Fort Worth if the city paid the railroad $75,000 ($2 million today) and provided the right-of-way. According to B. B. Paddock, a town hall meeting was called, the doors locked, and no one allowed to leave the room until the $75,000 and the money for the right-of-way had been raised by residents.

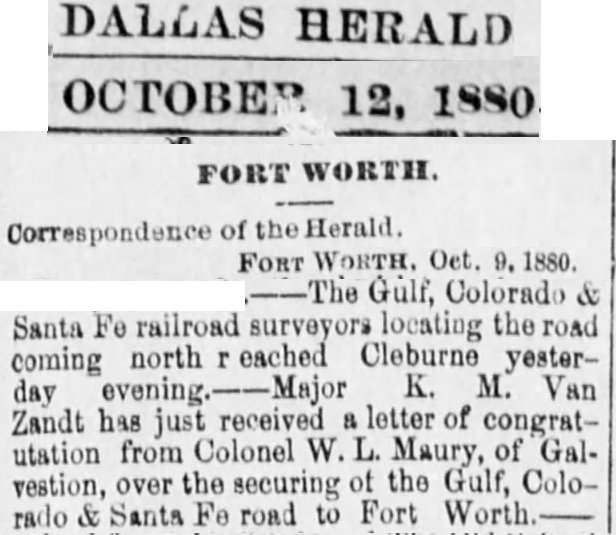

In October 1880 William Lewis Moody of Galveston, one of Van Zandt’s two friends on the Santa Fe board, congratulated Van Zandt on securing the railroad for Fort Worth. Moody and Van Zandt had fought together in the 7th Texas Infantry at the Battle of Fort Donelson in the Civil War, had been prisoners of war together after the Confederate defeat.

In October 1880 William Lewis Moody of Galveston, one of Van Zandt’s two friends on the Santa Fe board, congratulated Van Zandt on securing the railroad for Fort Worth. Moody and Van Zandt had fought together in the 7th Texas Infantry at the Battle of Fort Donelson in the Civil War, had been prisoners of war together after the Confederate defeat.

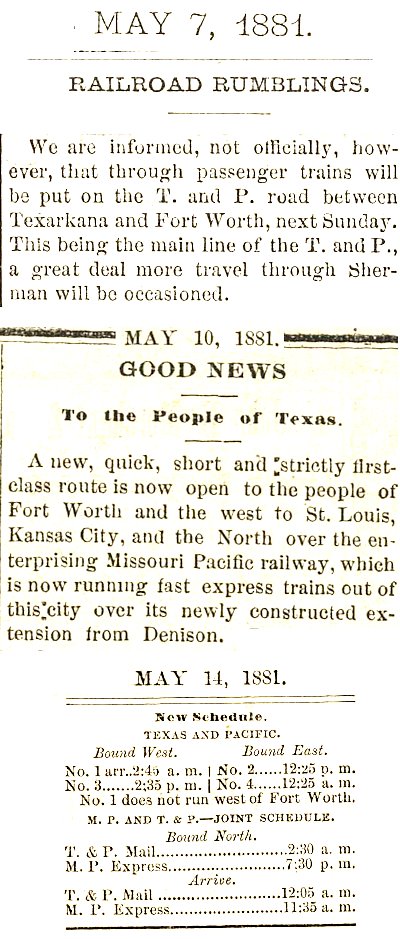

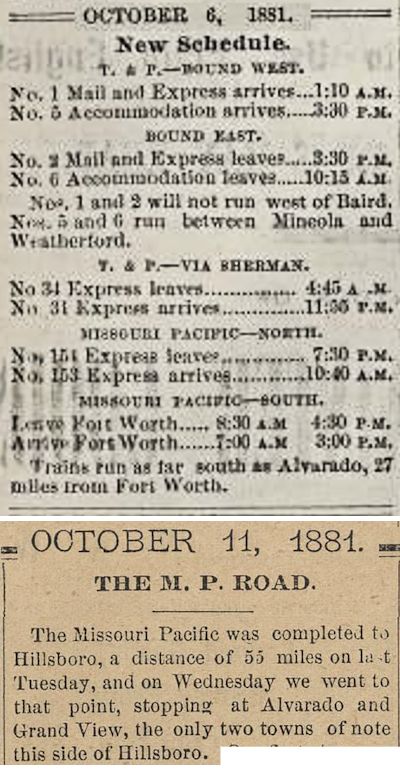

The next year, 1881, was monumental in Fort Worth’s rail history. In May the T&P opened a track north from Fort Worth to Sherman and east to Texarkana, contributing a third leg to the tarantula. This track was a twofer: Not only the T&P but also the Missouri Pacific railroad began serving Fort Worth on that track.

The next year, 1881, was monumental in Fort Worth’s rail history. In May the T&P opened a track north from Fort Worth to Sherman and east to Texarkana, contributing a third leg to the tarantula. This track was a twofer: Not only the T&P but also the Missouri Pacific railroad began serving Fort Worth on that track.

And in October the Missouri Pacific began serving Fort Worth from the south.

And in October the Missouri Pacific began serving Fort Worth from the south.

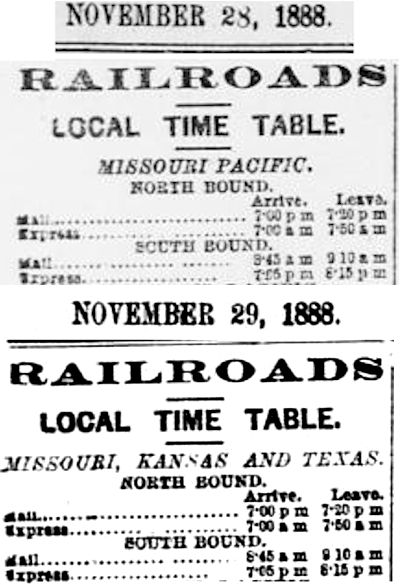

(On November 29, 1888 the Fort Worth Gazette railroad time table began listing the Missouri Pacific as “Missouri, Kansas and Texas” [Katy].)

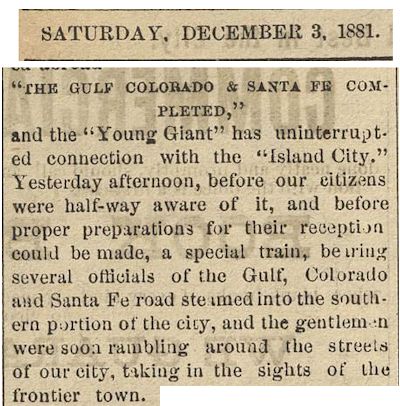

And the Santa Fe finally began service from the south in December 1881. In the clipping, “Young Giant”—like “City of Heights” and “Queen City of the Prairies”—was one of the Democrat’s nicknames for Fort Worth.

And the Santa Fe finally began service from the south in December 1881. In the clipping, “Young Giant”—like “City of Heights” and “Queen City of the Prairies”—was one of the Democrat’s nicknames for Fort Worth.

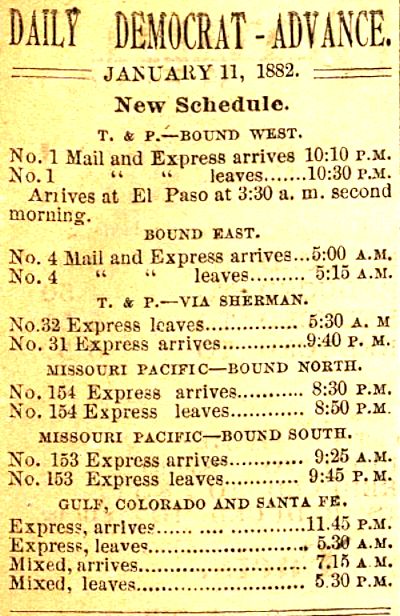

As the year 1882 began, thanks to Van Zandt and others, Fort Worth now was served by these rail lines: Texas & Pacific to the east, west, and north; Missouri Pacific to the north and south; Santa Fe to the south. Note that now the T&P extended all the way to El Paso, connecting with the Southern Pacific track to form the transcontinental line.

As the year 1882 began, thanks to Van Zandt and others, Fort Worth now was served by these rail lines: Texas & Pacific to the east, west, and north; Missouri Pacific to the north and south; Santa Fe to the south. Note that now the T&P extended all the way to El Paso, connecting with the Southern Pacific track to form the transcontinental line.

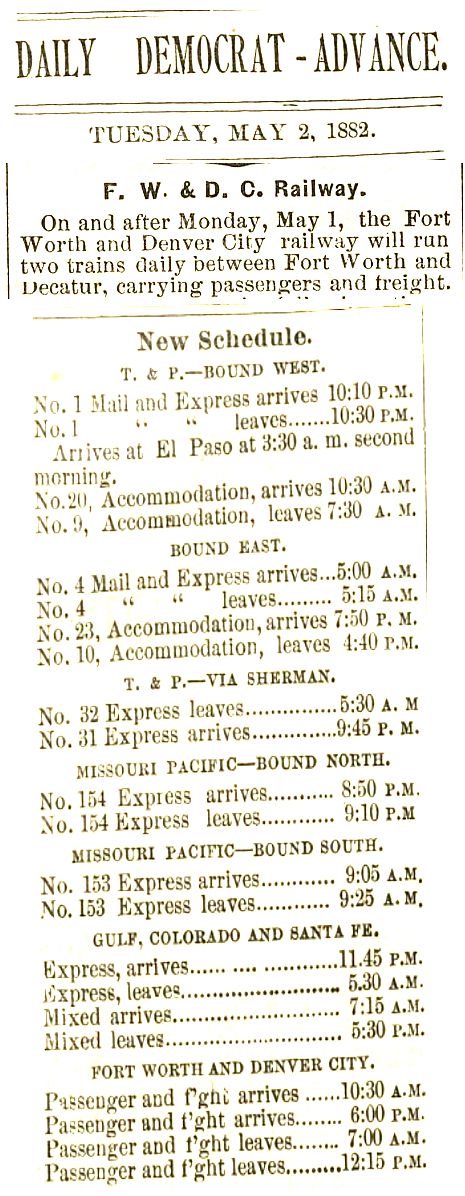

In May 1882 the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad began running—not to Denver but to Decatur. Completion of the track to Denver was six years away.

In May 1882 the Fort Worth & Denver City railroad began running—not to Denver but to Decatur. Completion of the track to Denver was six years away.

Also in 1882 Fort Worth got a new passenger station, located near today’s Tower 55 interlocking plant where the east-west and north-south tracks crossed. The new station was much grander than the little two-room station of 1876.

Also in 1882 Fort Worth got a new passenger station, located near today’s Tower 55 interlocking plant where the east-west and north-south tracks crossed. The new station was much grander than the little two-room station of 1876.

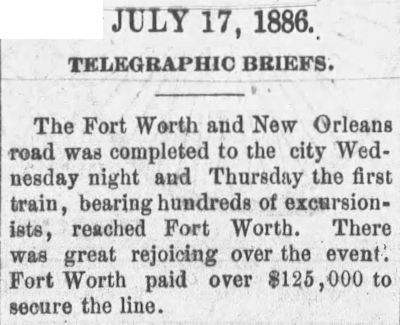

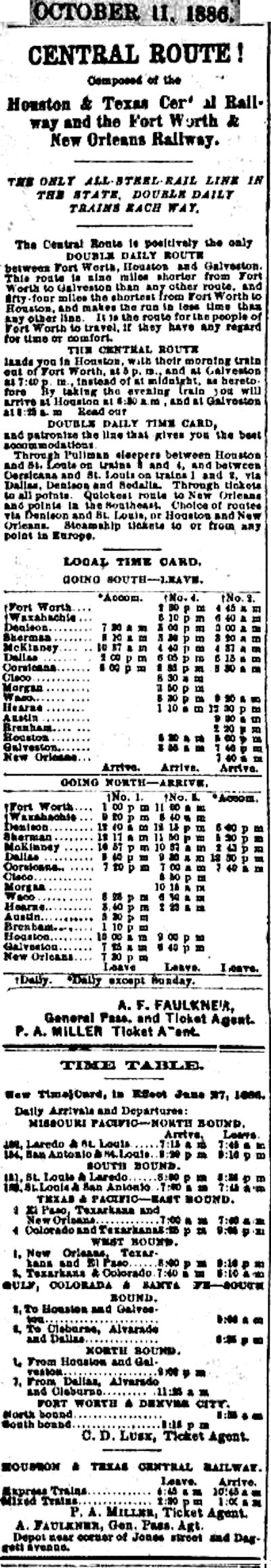

Fast-forward to 1886. In July the Fort Worth & New Orleans railroad began service from Waxahachie, where it connected with the Houston & Texas Central railroad. Note that Fort Worth paid FW&NO $125,000 ($3.6 million today) to bring its railroad to town. Now Fort Worth had five railroads.

Fast-forward to 1886. In July the Fort Worth & New Orleans railroad began service from Waxahachie, where it connected with the Houston & Texas Central railroad. Note that Fort Worth paid FW&NO $125,000 ($3.6 million today) to bring its railroad to town. Now Fort Worth had five railroads.

The FW&NO was soon acquired by the Houston & Texas Central.

The FW&NO was soon acquired by the Houston & Texas Central.

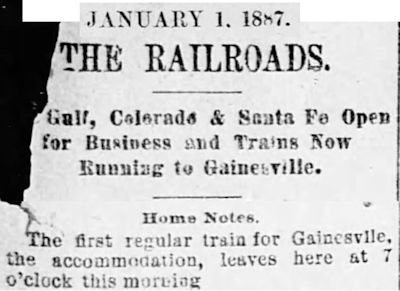

In January 1887 the Santa Fe put its second leg on the tarantula with a track running north. By my count, that track gave Paddock’s tarantula its eighth leg. It was now anatomically correct.

In January 1887 the Santa Fe put its second leg on the tarantula with a track running north. By my count, that track gave Paddock’s tarantula its eighth leg. It was now anatomically correct.

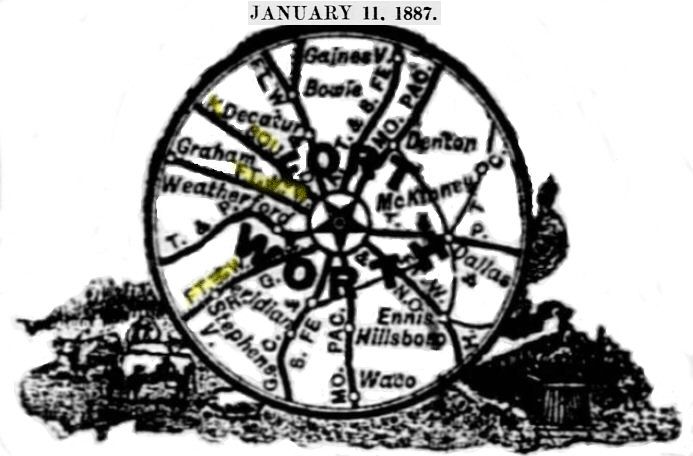

In fact, that same month a version of Paddock’s tarantula map became the centerpiece of the Gazette’s page 1 nameplate. The map shows eleven legs, but those highlighted in yellow did not exist per se.

In fact, that same month a version of Paddock’s tarantula map became the centerpiece of the Gazette’s page 1 nameplate. The map shows eleven legs, but those highlighted in yellow did not exist per se.

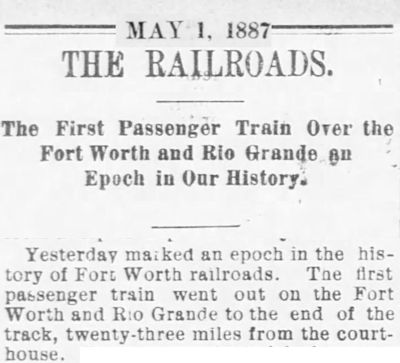

In May 1887 Paddock’s tarantula got its ninth leg, and Paddock got his own train set to play with: The Fort Worth & Rio Grande railroad began service. Paddock was president of the company.

In May 1887 Paddock’s tarantula got its ninth leg, and Paddock got his own train set to play with: The Fort Worth & Rio Grande railroad began service. Paddock was president of the company.

Paddock and other Fort Worth civic leaders, with financial backing by the Vanderbilt railroad syndicate, had an ambitious plan: to build a transcontinental route from New York to Fort Worth and across Mexico to the Pacific port of Topolobampo. Laying of track from Fort Worth began in November 1886. But by May 1887 only twenty-three miles had been laid.

Meanwhile the FW&RG was a major sponsor of the Texas Spring Palace exhibition in 1889-1890.

In 1901 the Fort Worth & Rio Grande was bought by the St. Louis & San Francisco (“Frisco,” see below) railroad.

Railroads often were chartered with plans to reach destinations they never reached. The Fort Worth & Rio Grande never reached the Rio Grande, much less the Pacific port of Topolobampo. The Frisco extended the line only as far as Menard—two hundred miles from Fort Worth.

And that’s a shame because Topolobampo surely would have been the most melodic destination ever for Fort Worth rail travelers.

“Topolobampo, Topolobampo,

ya no puede caminar.”

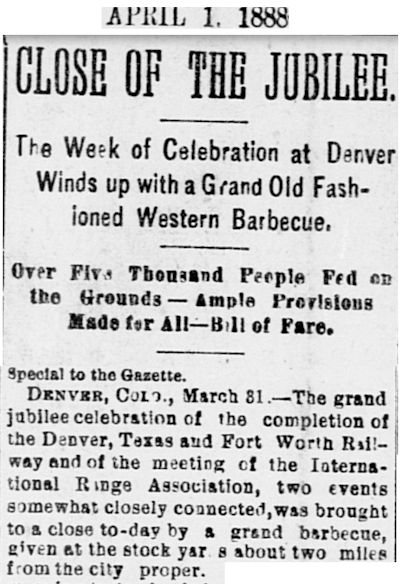

But the year 1888 did bring a success story: The Fort Worth & Denver City railroad finally reached Denver.

But the year 1888 did bring a success story: The Fort Worth & Denver City railroad finally reached Denver.

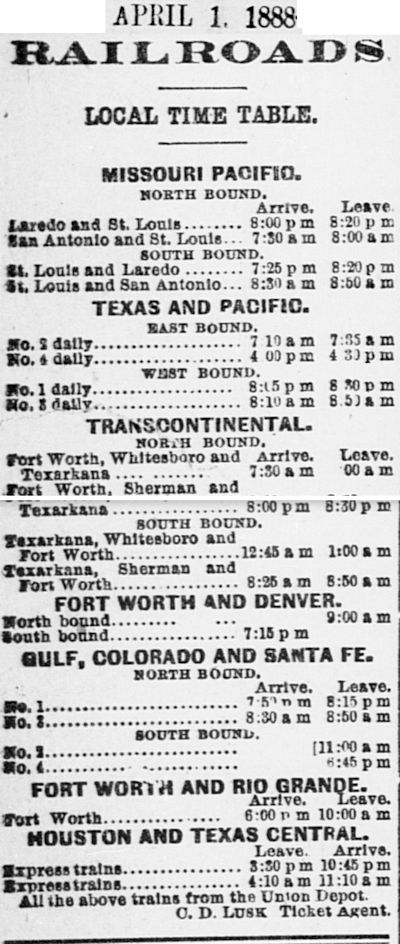

This time table of April 1888 shows seven railroad companies running trains over nine legs. The Missouri Pacific northern line ran on the T&P’s track to the north.

This time table of April 1888 shows seven railroad companies running trains over nine legs. The Missouri Pacific northern line ran on the T&P’s track to the north.

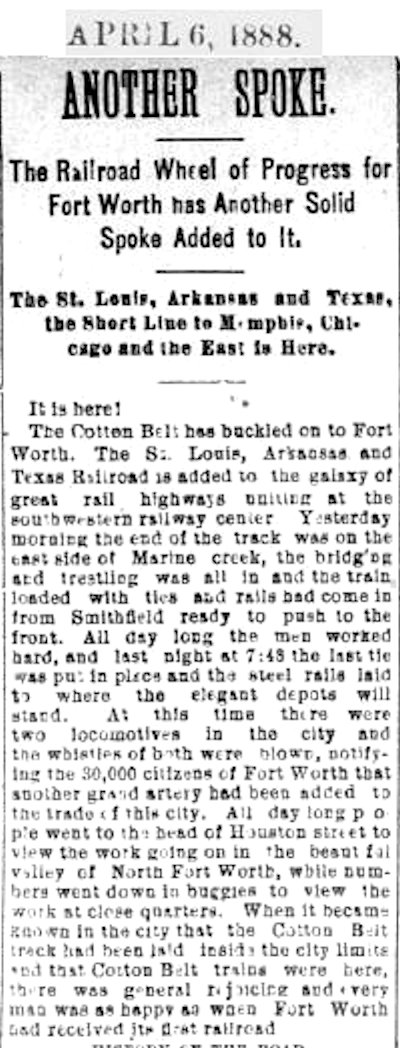

Also in April 1888 the St. Louis, Arkansas & Texas (later “St. Louis-Southwestern,” known as the “Cotton Belt”) railroad began service.

Also in April 1888 the St. Louis, Arkansas & Texas (later “St. Louis-Southwestern,” known as the “Cotton Belt”) railroad began service.

By 1890 Fort Worth’s population was 23,076 as the railroads continued to build the city.

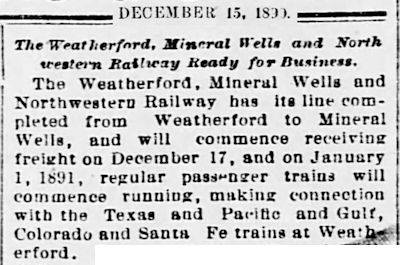

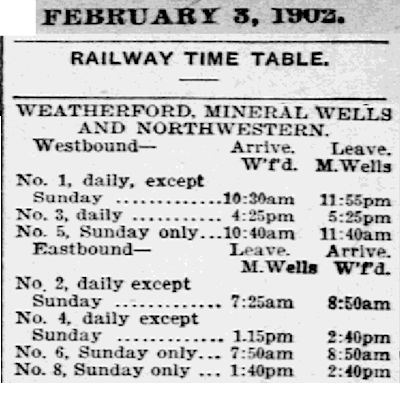

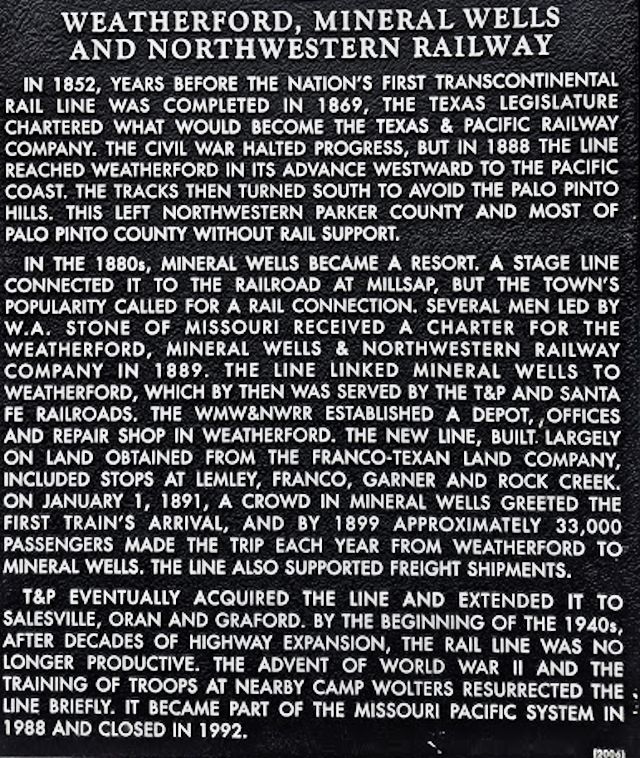

In 1890 a lesser-known railroad began operation. The Weatherford, Mineral Wells & Northwestern railroad operated between—you guessed it—Weatherford and Mineral Wells. Twenty miles. It also served the Acme brick plant at Bennett in Parker County.

Why do I include it in a chronology of Fort Worth railroads?

Because the Fort Worth newspapers included the WMW&N in its timetables. But as far as I can determine, the railroad merely connected in Weatherford with T&P trains westbound from Fort Worth.

Because the Fort Worth newspapers included the WMW&N in its timetables. But as far as I can determine, the railroad merely connected in Weatherford with T&P trains westbound from Fort Worth.

In fact, the Weatherford, Mineral Wells & Northwestern was bought by the T&P, which extended the line and operated it almost until the shortline’s centennial. The Missouri Pacific railroad acquired the line in 1988 and closed it in 1992 at age 102—a remarkably long life for a shortline.

In fact, the Weatherford, Mineral Wells & Northwestern was bought by the T&P, which extended the line and operated it almost until the shortline’s centennial. The Missouri Pacific railroad acquired the line in 1988 and closed it in 1992 at age 102—a remarkably long life for a shortline.

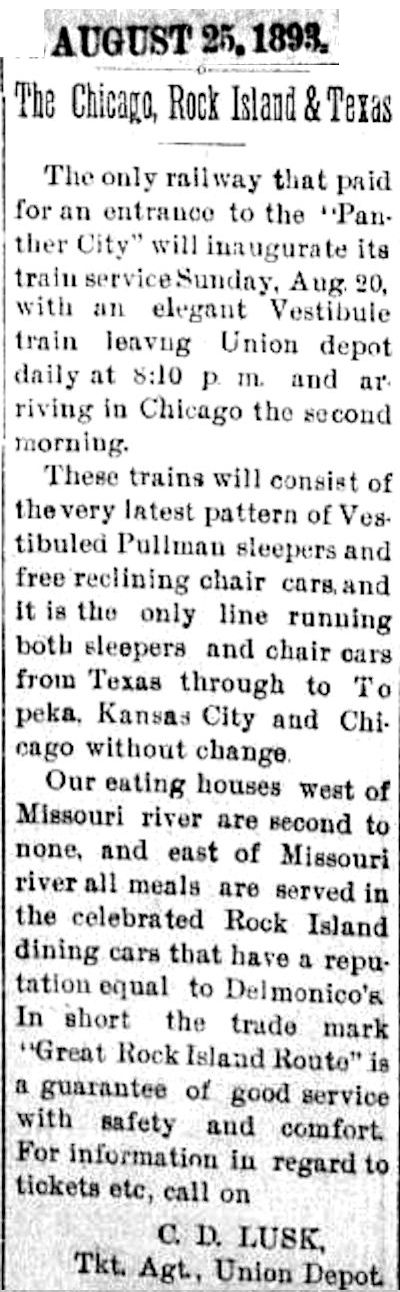

The Rock Island began service to Fort Worth south from Bowie on August 20, 1893.

The Rock Island began service to Fort Worth south from Bowie on August 20, 1893.

The ad claimed that the Rock Island was the only railroad that paid money—rather than received money—to serve Fort Worth.

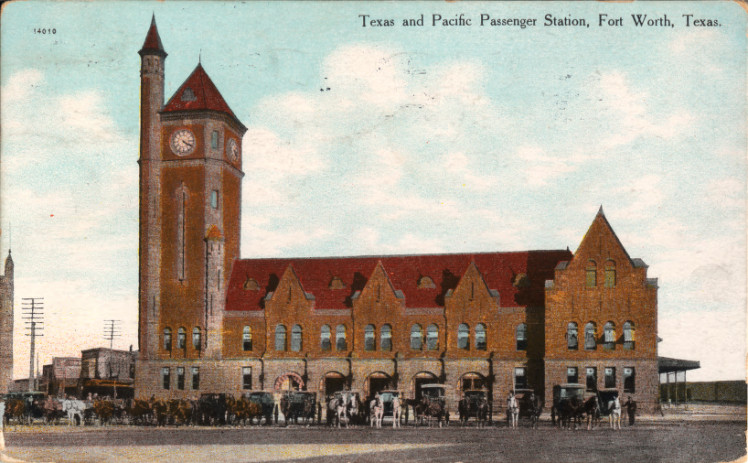

The year 1899 was another twofer for Fort Worth. Two new passenger stations opened: the Texas & Pacific on Main Street and the Union Station (Santa Fe) on Jones Street. The Fort Worth Register gave very little coverage to the Santa Fe opening.

The year 1899 was another twofer for Fort Worth. Two new passenger stations opened: the Texas & Pacific on Main Street and the Union Station (Santa Fe) on Jones Street. The Fort Worth Register gave very little coverage to the Santa Fe opening.

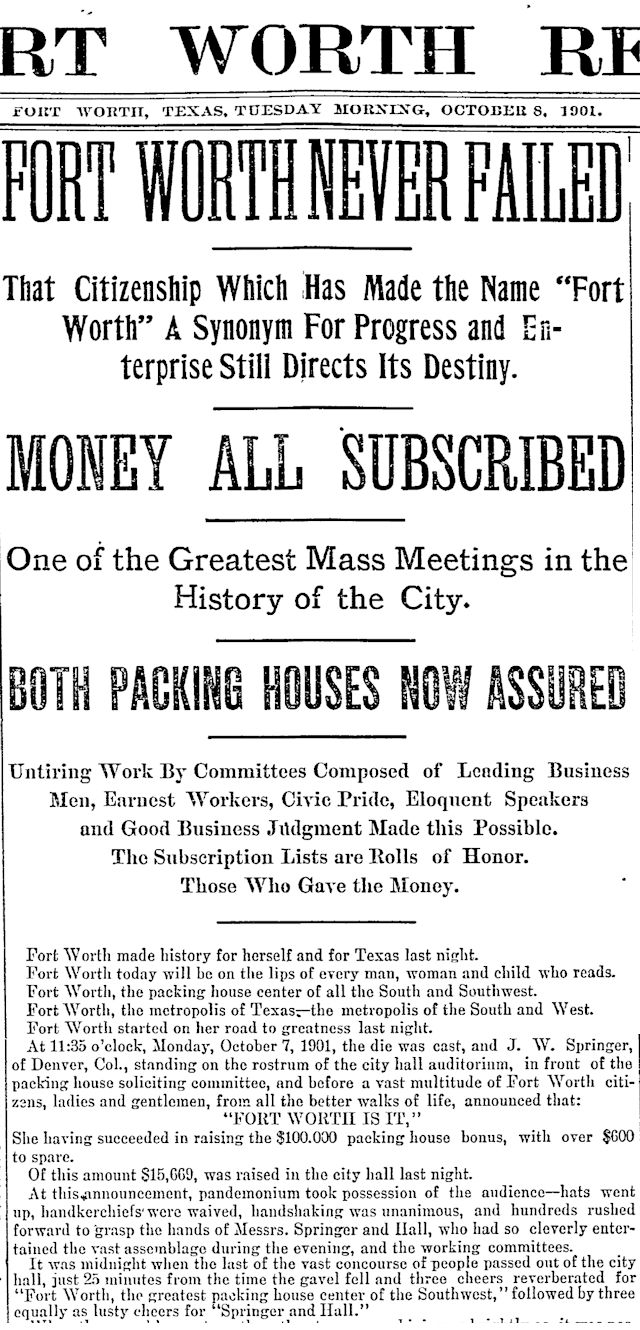

Railroads built towns not only because railroads were an economic boon in their own right but also because railroads had a ripple effect. In 1901 when Swift and Armour packing companies agreed to come to town, their decision was made in part because Fort Worth by then had become a railroad center. Soon the packing plants and reorganized stockyards would join the railroads as major employers. In 1900 Fort Worth’s population was 26,668. In 1910 the population was 73,312.

Railroads built towns not only because railroads were an economic boon in their own right but also because railroads had a ripple effect. In 1901 when Swift and Armour packing companies agreed to come to town, their decision was made in part because Fort Worth by then had become a railroad center. Soon the packing plants and reorganized stockyards would join the railroads as major employers. In 1900 Fort Worth’s population was 26,668. In 1910 the population was 73,312.

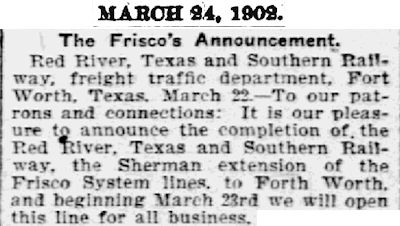

On March 23, 1902 the St. Louis & San Francisco (Frisco) railroad began service.

On March 23, 1902 the St. Louis & San Francisco (Frisco) railroad began service.

But despite its name, the Frisco never reached San Francisco.

March 23, 1902 was another twofer day for Fort Worth. On that day the Red River, Texas & Southern railroad began service. The Red River, Texas & Southern had been chartered in 1901 to build a railroad from the Red River in Grayson County south to Fort Worth. Except for four miles of new track in Fort Worth, the Red River, Texas & Southern used Cotton Belt track into Fort Worth. In 1904 the Red River, Texas & Southern railroad merged with the Frisco line.

March 23, 1902 was another twofer day for Fort Worth. On that day the Red River, Texas & Southern railroad began service. The Red River, Texas & Southern had been chartered in 1901 to build a railroad from the Red River in Grayson County south to Fort Worth. Except for four miles of new track in Fort Worth, the Red River, Texas & Southern used Cotton Belt track into Fort Worth. In 1904 the Red River, Texas & Southern railroad merged with the Frisco line.

A Red River, Texas & Southern trestle still spans the Trinity River near Oakwood Cemetery.

A Red River, Texas & Southern trestle still spans the Trinity River near Oakwood Cemetery.

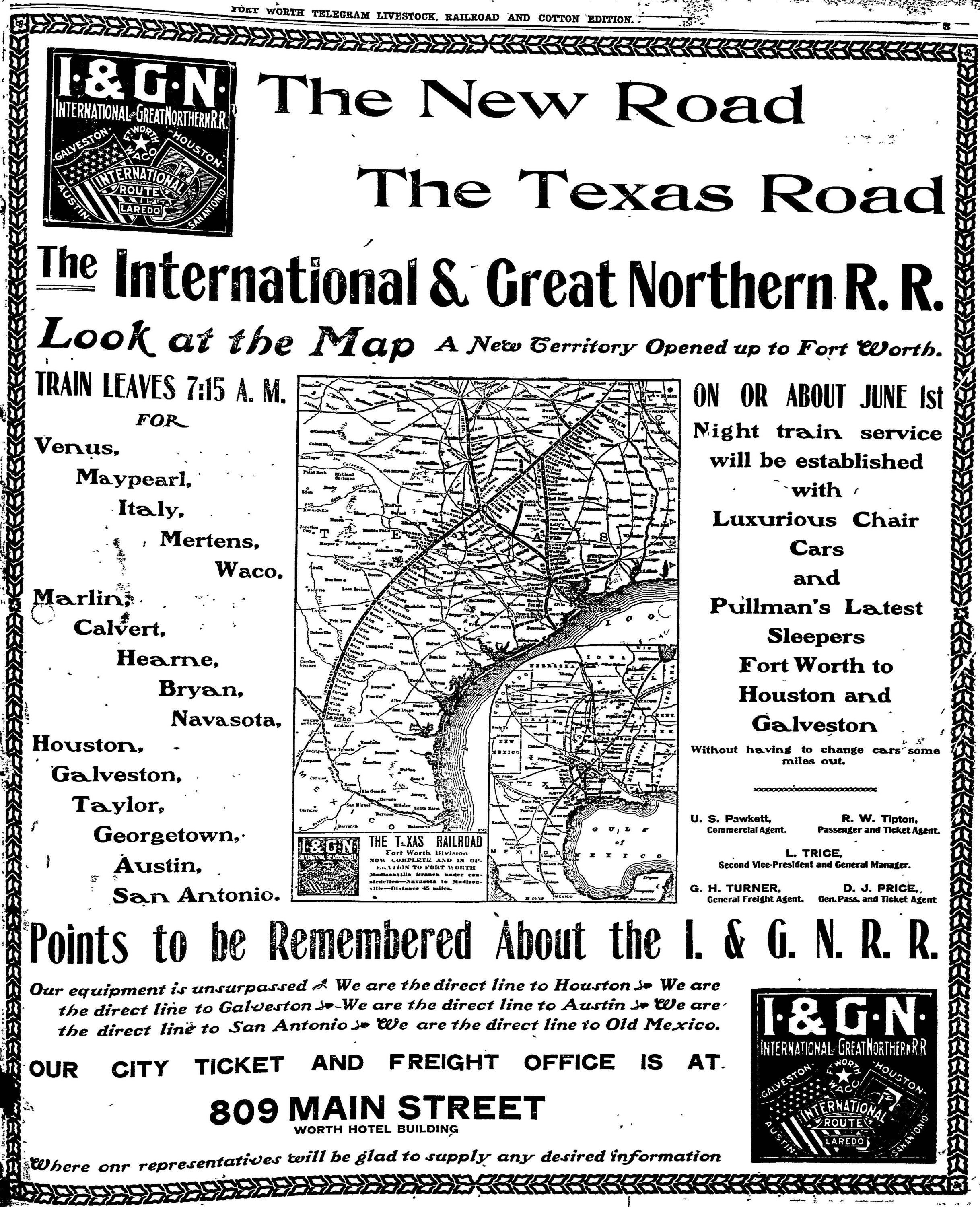

In April 1903 the International & Great Northern railroad began service to the south. Despite its name, the International & Great Northern was neither international nor northern. It was a Texas railroad between Fort Worth and Galveston and Longview and Laredo.

In April 1903 the International & Great Northern railroad began service to the south. Despite its name, the International & Great Northern was neither international nor northern. It was a Texas railroad between Fort Worth and Galveston and Longview and Laredo.

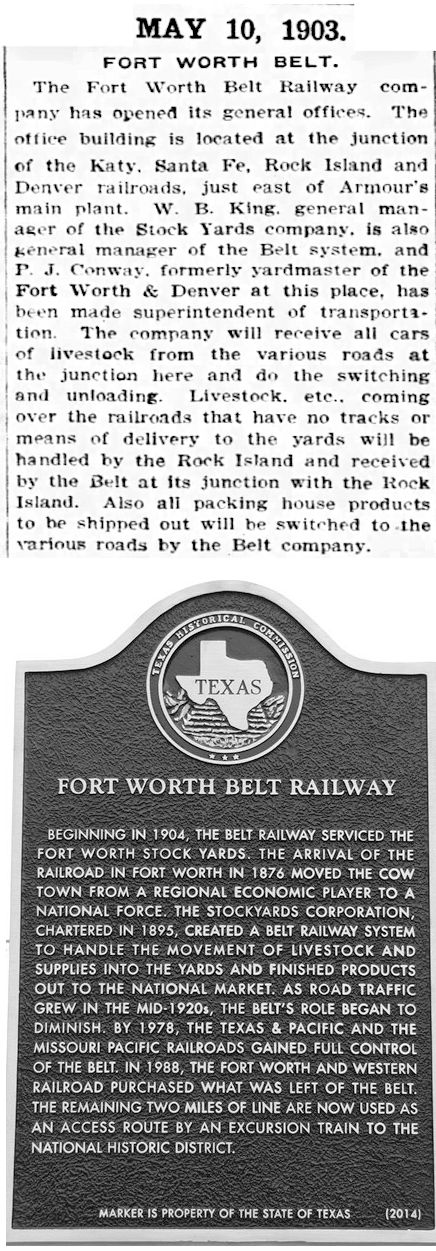

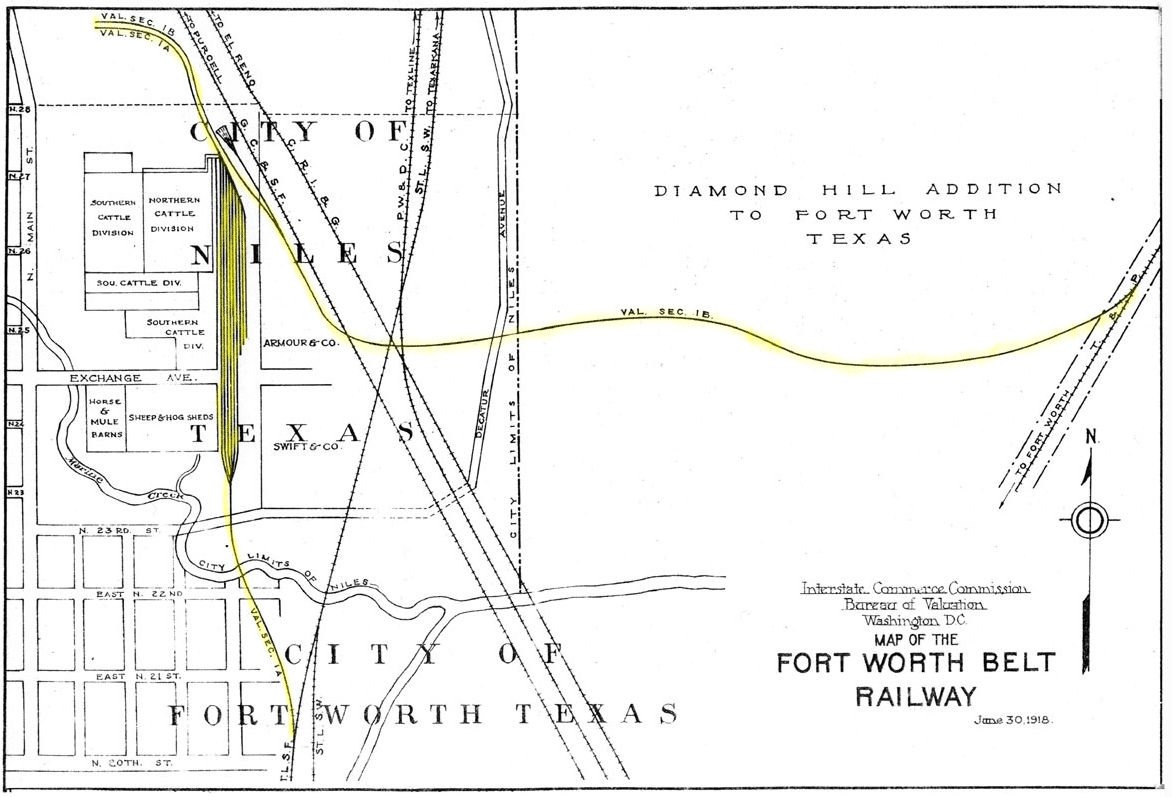

In May 1903 Paddock’s tarantula got yet another leg—a very short one. The Fort Worth Belt Railway opened its offices at the stockyards-packing plants complex in Niles City.

In May 1903 Paddock’s tarantula got yet another leg—a very short one. The Fort Worth Belt Railway opened its offices at the stockyards-packing plants complex in Niles City.

The Fort Worth Belt Railway was a terminal line with only three miles of main-line track and fifteen miles of yard track and sidings. It was founded for a specific purpose: to move livestock and livestock products between the various main-line railroads and the packing plants and stockyards.

The Fort Worth Belt Railway was a terminal line with only three miles of main-line track and fifteen miles of yard track and sidings. It was founded for a specific purpose: to move livestock and livestock products between the various main-line railroads and the packing plants and stockyards.

The Fort Worth Belt Railway was merged into the Missouri Pacific network in 1978.

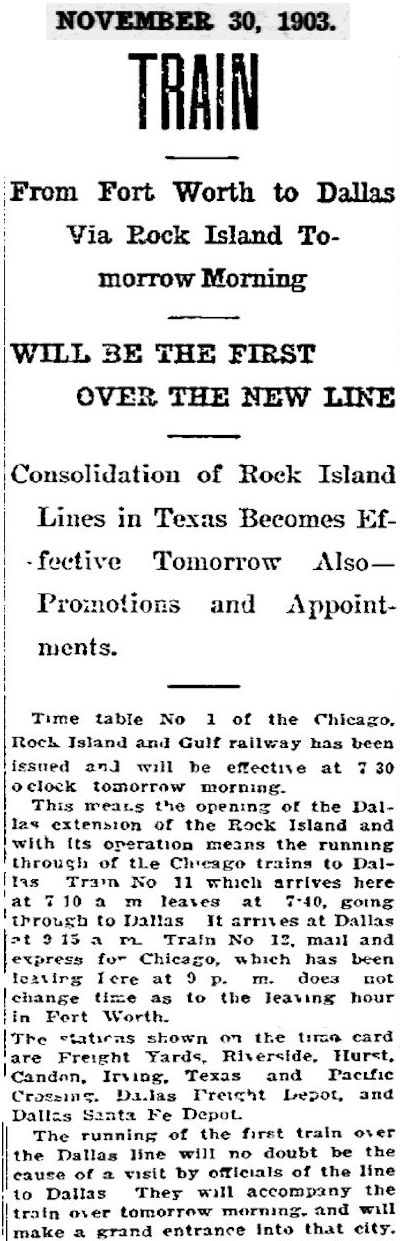

In December 1903 the Rock Island added a second line—from Dallas. Towns, including Hurst, Candor (Euless today), and Irving, sprang up as the track was laid.

In December 1903 the Rock Island added a second line—from Dallas. Towns, including Hurst, Candor (Euless today), and Irving, sprang up as the track was laid.

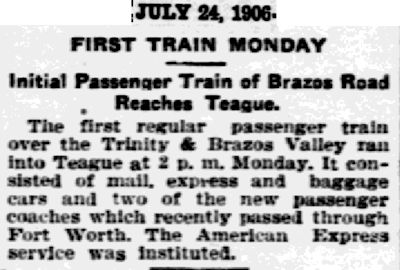

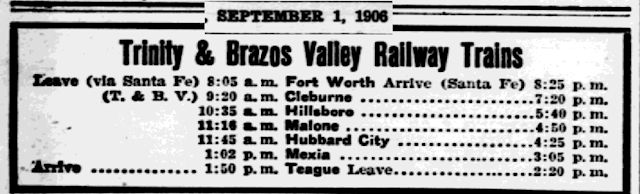

In July 1906 another lesser-known railroad began service to Fort Worth: the Trinity & Brazos Valley. The T&BV ran mostly on its own track but ran on Santa Fe track between Fort Worth and Cleburne. The company operated from Fort Worth through Teague to Houston and Galveston.

In July 1906 another lesser-known railroad began service to Fort Worth: the Trinity & Brazos Valley. The T&BV ran mostly on its own track but ran on Santa Fe track between Fort Worth and Cleburne. The company operated from Fort Worth through Teague to Houston and Galveston.

As far as I can tell, after Fort Worth added the Trinity & Brazos Valley in 1906 Fort Worth added no railroads until the Fort Worth & Western in 1988.

The first railroad—Texas & Pacific—and the last railroad—Trinity & Brazos Valley—were separated by seventy years.

As the twentieth century began railroads were the biggest industry in the nation, although the industry began to decline after World War I.

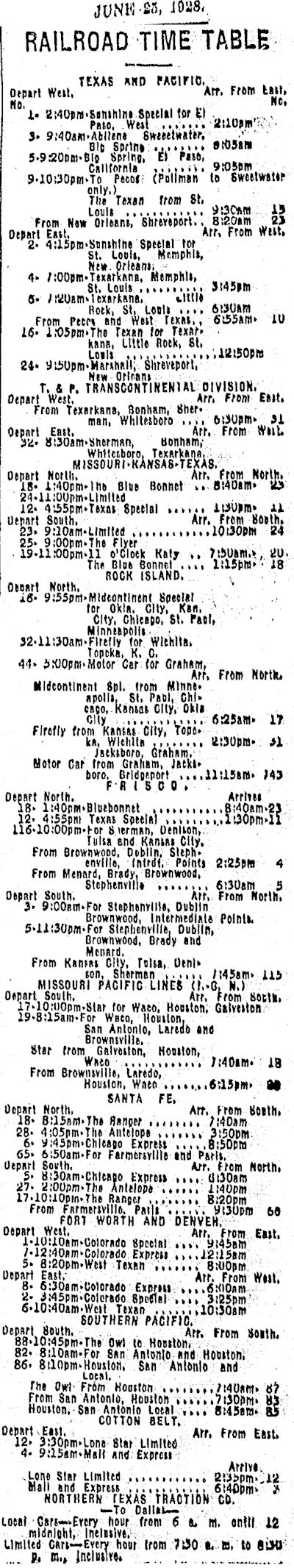

This 1928 time table shows an impressive number of trains serving Fort Worth.

This 1928 time table shows an impressive number of trains serving Fort Worth.

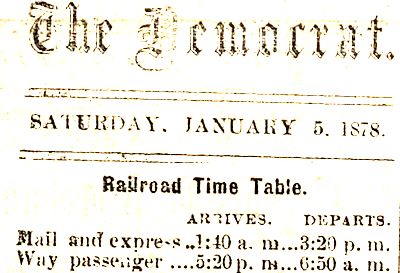

Compare it with this time table from 1878.

Compare it with this time table from 1878.

But the June 1928 time table apparently was the last one printed in the Star-Telegram. The fact that after a half-century a Fort Worth newspaper was no longer printing a railroad time table was telling.

Indeed nationally railroads would be hurt by the Great Depression and would continue to decline after World War II even as railroads tried to remain attractive to travelers by adding amenities and diesel engines.

For example, the Texas & Pacific railroad spent $13 million ($202 million today) in Fort Worth in the late 1920s and early 1930s, building a new railyard, new underpasses, a new passenger station, and a new freight depot.

For example, the Texas & Pacific railroad spent $13 million ($202 million today) in Fort Worth in the late 1920s and early 1930s, building a new railyard, new underpasses, a new passenger station, and a new freight depot.

But the decline of the railroads continued. Gradually the newspaper time tables shrank and then disappeared. Small railroads were taken over by big railroads; some railroads ceased operation; people increasingly traveled by automobiles, buses, and airplanes; freight was increasingly shipped by truck, not train. The interstate highway system, authorized in 1956, would drive yet another railroad spike into the coffin.

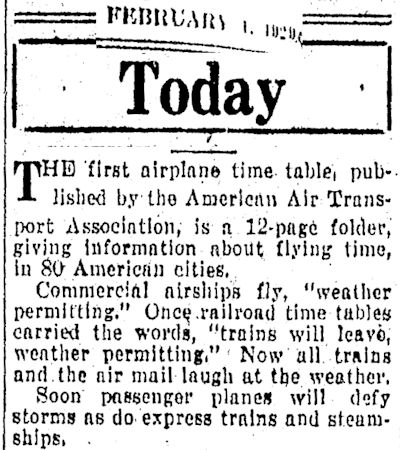

Railroad time tables were replaced by airline time tables.

Railroad time tables were replaced by airline time tables.

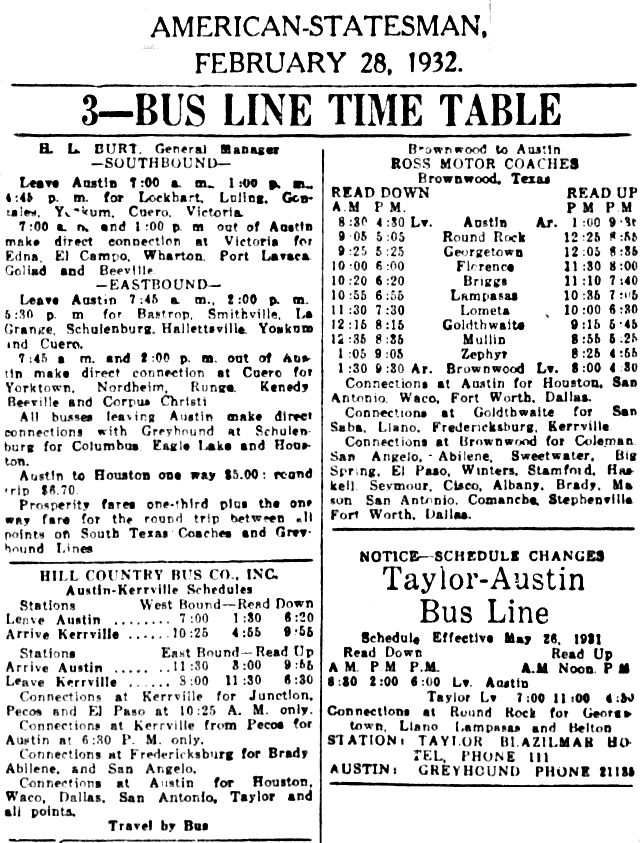

And bus time tables.

And bus time tables.

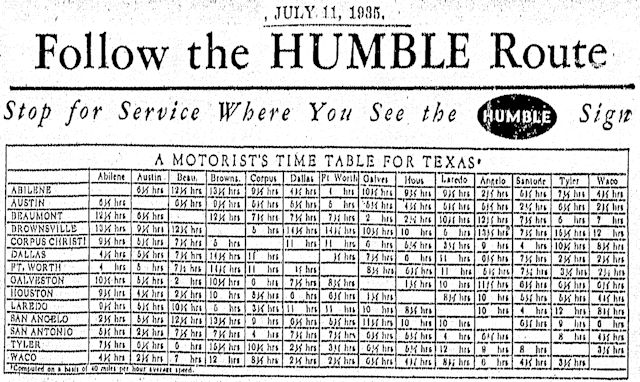

And automobile time tables.

And automobile time tables.

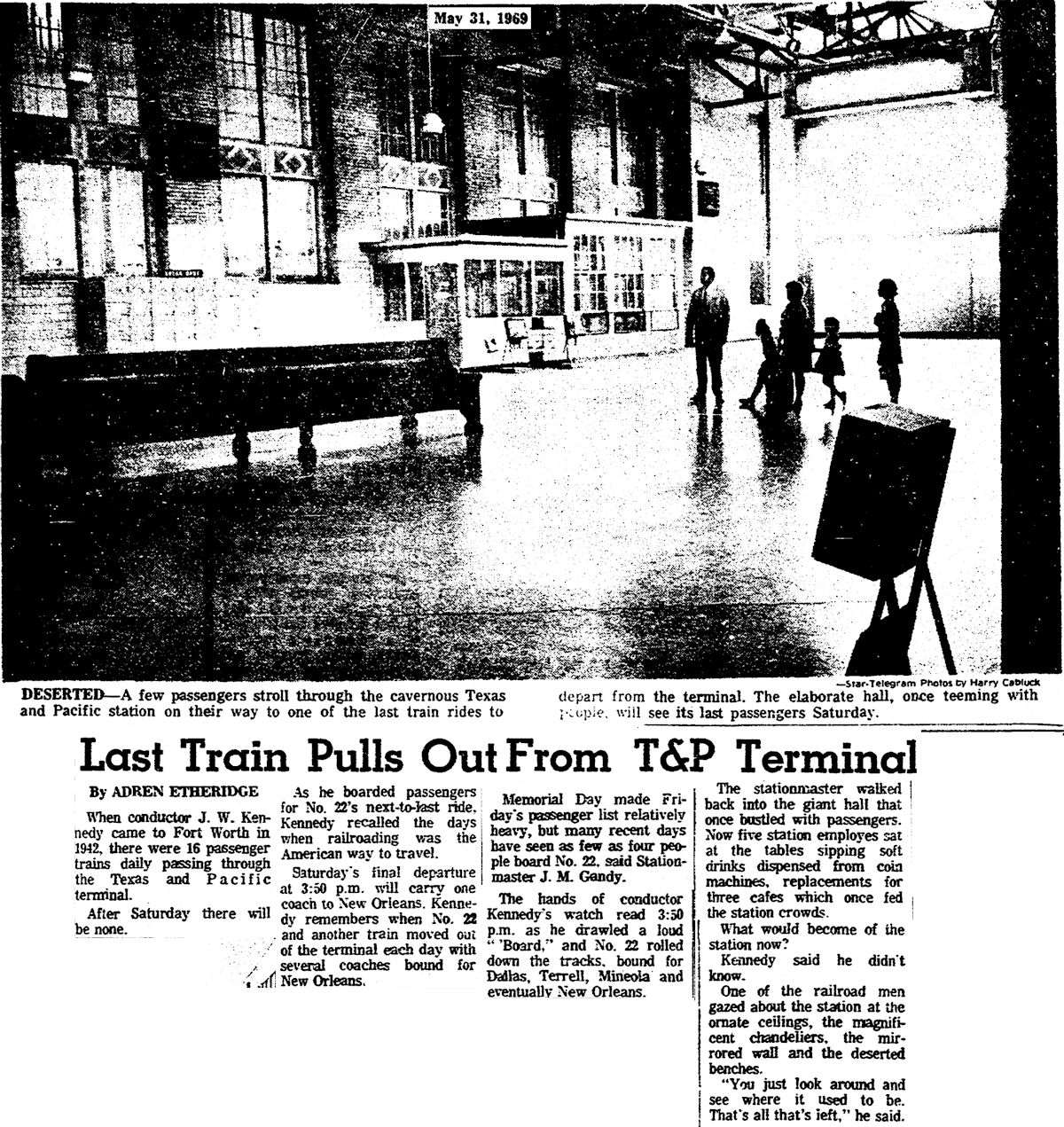

Even the mighty Texas & Pacific, which had given Paddock’s tarantula its first three legs, reached the end of the line. The last T&P passenger train—the Texas Eagle—left the Texas & Pacific terminal in 1969—ninety-three years after the first one arrived.

Even the mighty Texas & Pacific, which had given Paddock’s tarantula its first three legs, reached the end of the line. The last T&P passenger train—the Texas Eagle—left the Texas & Pacific terminal in 1969—ninety-three years after the first one arrived.

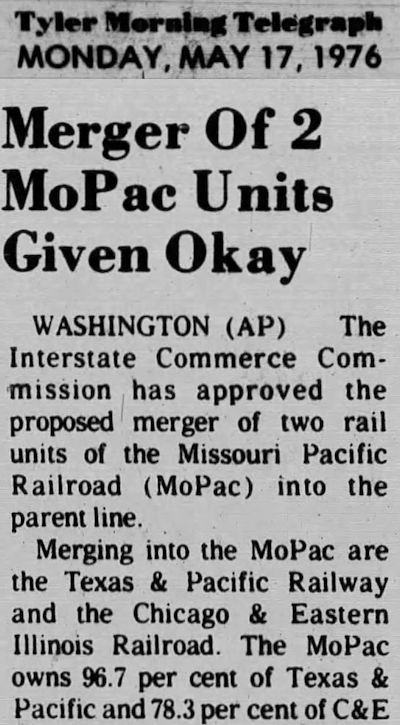

Seven years later Texas & Pacific was consumed in a merger with parent company Missouri Pacific, which in turn soon was consumed by Union Pacific. A century after the Texas & Pacific entered Fort Worth, the T&P brand was gone.

Seven years later Texas & Pacific was consumed in a merger with parent company Missouri Pacific, which in turn soon was consumed by Union Pacific. A century after the Texas & Pacific entered Fort Worth, the T&P brand was gone.

But despite the decline of the industry, Fort Worth continues to be a railroad town with live tracks in all directions. Tower 55 remains one of the busiest rail intersections in the nation. The Union Pacific railroad operates its Davidson yard here. Fort Worth is headquarters of the Fort Worth & Western railroad. Freight rumbles through town on the Union Pacific and the Burlington Northern Santa Fe tracks. Two Amtrak passenger trains arrive daily. Commuter rail lines are the Trinity Railway Express and TEXRail.

The era of the city-builders is past, but after 146 years, B. B. Paddock’s tarantula has shown that indeed it still has legs.

Posts About Trains and Trolleys