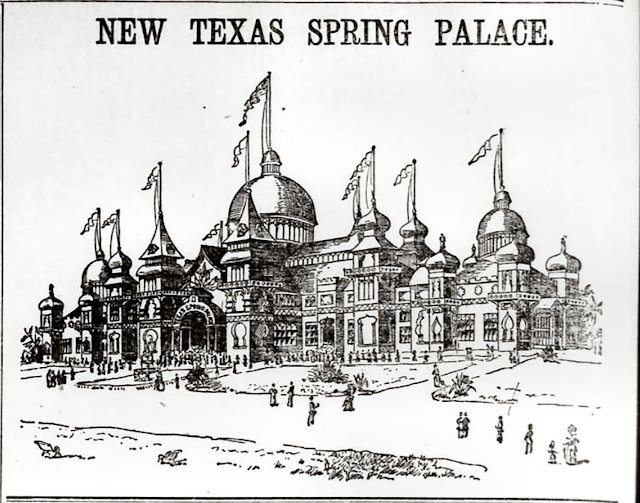

On May 30, 1890 the Texas Spring Palace exhibition (see Part 1) was nearing the end of its second season.

May 31 would be the final day. Seven thousand people, many of them from out of town, filled the palace on the night of May 30.

May 31 would be the final day. Seven thousand people, many of them from out of town, filled the palace on the night of May 30.

The exhibit’s second annual grand ball would be held on the night of May 30. The Gazette on May 29 had given a preview of the ball and had written that “nothing now but the unpropitious elements can hinder a brilliant ball on Friday night.”

The exhibit’s second annual grand ball would be held on the night of May 30. The Gazette on May 29 had given a preview of the ball and had written that “nothing now but the unpropitious elements can hinder a brilliant ball on Friday night.”

And that was fate’s cue.

At 10:25 p.m. Friday, at the conclusion of the regular evening concert, the lower floor of the palace was being cleared for the ball. According to one witness, a boy, perhaps dancing for pocket change from bystanders, stepped on a “parlor match” near the Gold Room on the second floor of the sprawling wooden building. The match head ignited. The flame from the match (“the deadly lucifer,” the Weekly Gazette later called it) ignited dry pampas grass that covered a pillar. In moments the “most beautiful structure ever erected on earth” was a beautiful bonfire. The fire fed at first on the flammable decor—on the dried grasses, moss, leaves, cotton bolls, cornstalks, wheat sheaves, paper, oilcloth, and fabric—and then on the building’s wooden frame. To the element of fire, a structure like the Texas Spring Palace was an all-you-can-eat buffet.

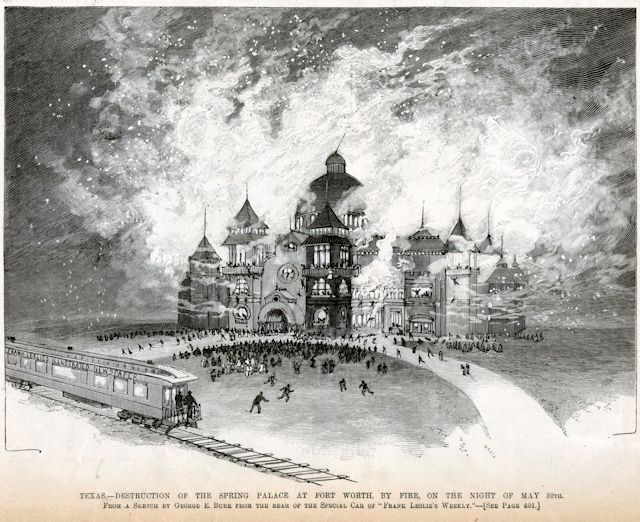

Journalists of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper were touring the South in a special railroad car and happened to be covering the Texas Spring Palace exhibition that night. A Leslie’s artist captured this scene from the railroad car parked on a siding. (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper image from Pete Charlton.)

Journalists of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper were touring the South in a special railroad car and happened to be covering the Texas Spring Palace exhibition that night. A Leslie’s artist captured this scene from the railroad car parked on a siding. (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper image from Pete Charlton.)

Leslie’s wrote that as the ball was about to begin “a boy stepped on a match near the base of a decorated column, and the tiny spark thus created . . . enveloped the entire upper floor in less than a hundred seconds.”

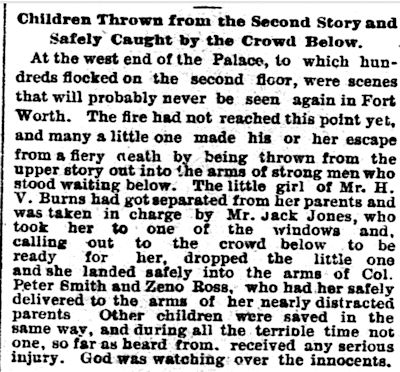

As the alarm of fire spread, evacuation of the first floor was relatively calm. But on the second floor, where the fire began and where stairways were the only route to safety, people panicked. Doors and stairways were clogged with fleeing people. One stairway handrail collapsed, and people fell over the side to the ground floor. As people fled, many of them were burned, of course. But people also were injured as they fell and were trampled in the rush to safety. People who jumped from windows to the ground suffered broken ankles and other injuries upon impact. The luckier ones jumped from windows into the arms of rescuers waiting below.

The Weekly Gazette reported that the last person to leave the flaming building was Texas Spring Palace president B. B. Paddock. As people fled the fire, he stood at the band stand urging calm, like the captain at the bridge of a sinking ship.

The building burned so quickly that firefighters could not save any part of it. The “most beautiful structure ever erected on earth” was a total loss. Dozens of birds and other animals in cages died. Valuable works of art and history on display were destroyed.

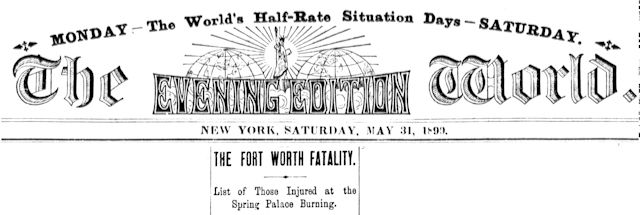

The Daily Gazette’s page 1 story about the fire has been torn from the archived copy of the May 31 newspaper, so we must look elsewhere for next-day coverage. The fire was front-page news in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World . . .

The Daily Gazette’s page 1 story about the fire has been torn from the archived copy of the May 31 newspaper, so we must look elsewhere for next-day coverage. The fire was front-page news in Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World . . .

and in the Galveston Daily News. Galveston in ten years would suffer an immeasurably greater calamity. (As often happened with first reports by newspapers, “Terrible Loss of Life” would prove an exaggeration.) . . .

and in the Galveston Daily News. Galveston in ten years would suffer an immeasurably greater calamity. (As often happened with first reports by newspapers, “Terrible Loss of Life” would prove an exaggeration.) . . .

and in the Dallas Weekly Times Herald, which waxed purple about the “great calamity.”

and in the Dallas Weekly Times Herald, which waxed purple about the “great calamity.”

On June 4 individuals and groups from around the state expressed their sympathy to the exhibition management. The Gazette also reported on the condition of some of the fire victims.

On June 4 individuals and groups from around the state expressed their sympathy to the exhibition management. The Gazette also reported on the condition of some of the fire victims.

On June 4 the Gazette also printed the reaction of newspapers in other cities.

On June 4 the Gazette also printed the reaction of newspapers in other cities.

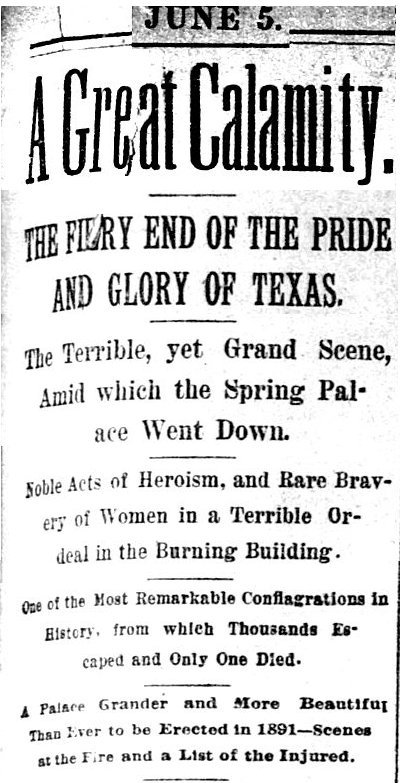

The Weekly Gazette on June 5 devoted a full page to the fire.

The Weekly Gazette on June 5 devoted a full page to the fire.

“The fiery end of the pride and glory of Texas,” the Weekly Gazette proclaimed. It, too, used the phrase “great calamity.”

“The fiery end of the pride and glory of Texas,” the Weekly Gazette proclaimed. It, too, used the phrase “great calamity.”

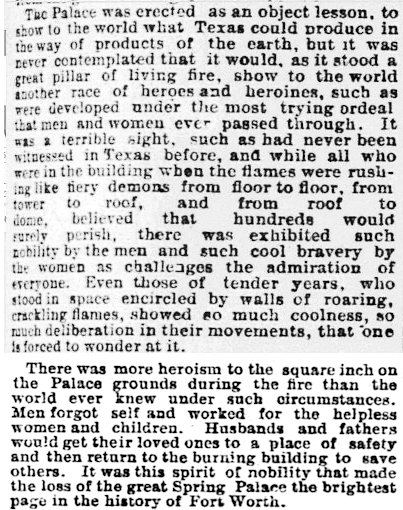

Even in a fire as sudden and all-sweeping as this one, heroes step forward. The Gazette praised “the heroes and heroines” of “the most trying ordeal that men and women ever passed through.”

Even in a fire as sudden and all-sweeping as this one, heroes step forward. The Gazette praised “the heroes and heroines” of “the most trying ordeal that men and women ever passed through.”

The Gazette reported rescues such as this one—involving John Peter Smith. (Come August 4 Smith would replace the disgraced William S. Pendleton as mayor.)

The Gazette reported rescues such as this one—involving John Peter Smith. (Come August 4 Smith would replace the disgraced William S. Pendleton as mayor.)

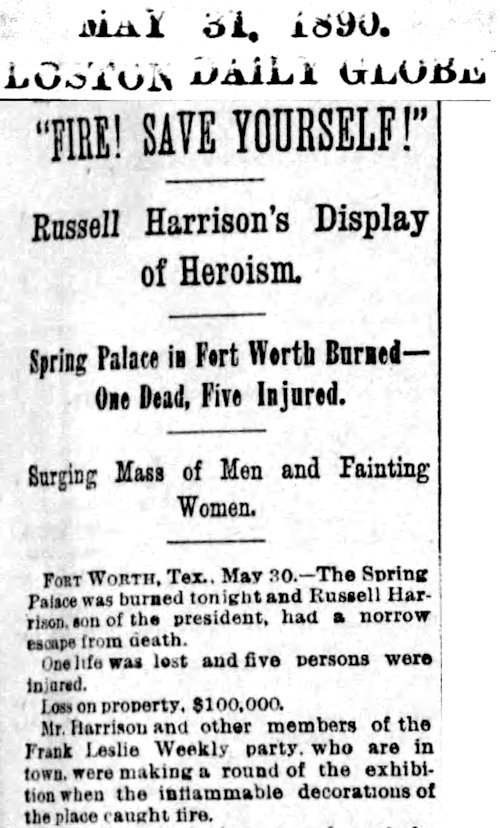

Russell Harrison, son of President Benjamin Harrison, was co-publisher of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. He was touring the exhibition when the fire began. Harrison saw a child who had fallen asleep in a corner of the second floor and tried to ascend a staircase to reach her, but he could not make any headway against the frightened people rushing down the staircase. Instead he turned to the “surging mass of men and fainting women.”

Russell Harrison, son of President Benjamin Harrison, was co-publisher of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. He was touring the exhibition when the fire began. Harrison saw a child who had fallen asleep in a corner of the second floor and tried to ascend a staircase to reach her, but he could not make any headway against the frightened people rushing down the staircase. Instead he turned to the “surging mass of men and fainting women.”

The Boston Daily Globe wrote: “‘Stand still,’ shouted Harrison. ‘Stay where you are and pass out orderly.’ Mr. Harrison stood his ground, begging the terrified women not to give way and helping to extricate them from the crowding mass . . .”

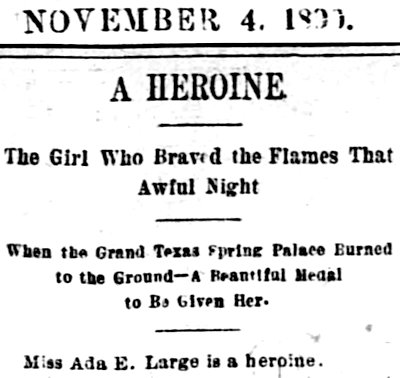

Ada Large, age fifteen, was a volunteer worker at the exhibition. The Gazette wrote: “When the cry of fire rang through the Spring Palace . . . Not selfishly seeking to make secure her own flight, she cast about for any unfortunates who might need succor, and perceiving the numbers of children playing about, set herself to providing their safety. Unceasingly she labored. Not until every living thing had left the palace, not until her own clothing hail been burned and torn to shreds and her skin in places was parched and blistered, could she be induced to leave.”

Ada Large, age fifteen, was a volunteer worker at the exhibition. The Gazette wrote: “When the cry of fire rang through the Spring Palace . . . Not selfishly seeking to make secure her own flight, she cast about for any unfortunates who might need succor, and perceiving the numbers of children playing about, set herself to providing their safety. Unceasingly she labored. Not until every living thing had left the palace, not until her own clothing hail been burned and torn to shreds and her skin in places was parched and blistered, could she be induced to leave.”

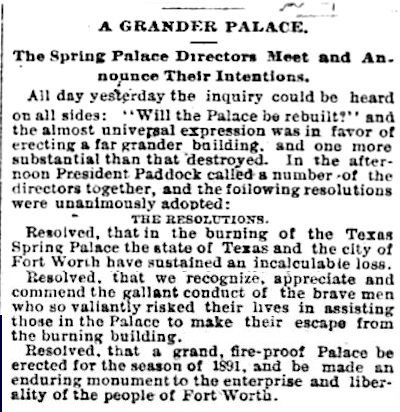

Dazed but undaunted, Texas Spring Palace president Paddock and the directors resolved that Fort Worth would resurrect the Texas Spring Palace—“fire-proof” next time. But factors, including the economic depression of 1893, would prevent that resurrection.

Dazed but undaunted, Texas Spring Palace president Paddock and the directors resolved that Fort Worth would resurrect the Texas Spring Palace—“fire-proof” next time. But factors, including the economic depression of 1893, would prevent that resurrection.

Paddock would later write, “The Spring Palace, which was a credit to the public spirit of the people of Fort Worth, went out in a blaze of glory.”

In that “blaze of glory” several hundred people were injured but only forty-three seriously.

And remarkably only one person died:

Texas Spring Palace (Part 3): “No Truer Hero Ever Died”

Footnote: Seven of Fort Worth’s early fires (four of them on railroad property) occurred in the area between Lancaster Avenue and Hattie Street south of downtown: Spring Palace (1890), 1882 T&P passenger depot (1896), 1899 T&P passenger depot (1904), Fifth Ward school and Missouri Avenue Methodist Church (1904), 1902 T&P freight depot (1908), South Side (1909), Fort Worth High School (1910).

Great report, Mike, as always. The writers of the time were also very good. But we need to dig deeper. Something was afoot. All those destructive fires in a small area. Serial arsonist? The occult? Was there a full moon at each of the major fires? At any rate this would be a great movie.

The area south of Lancaster certainly has had more than its share of fires.