When Ed Terrell first came to town, there was no town. Not even an Army fort. Texas had yet to enter the Union. Ripley Allen Arnold and William Jenkins Worth had yet to fight in the Mexican-American War. And whereas today we hear the drone of traffic, the wail of sirens, and the clatter of construction, in 1841 Ed Terrell heard, according to the 1877 city directory, “the howl of the lone wolf, the shriek of the prowling panther, the neigh of the wild horse, and [the] yell of the wandering savage.”

The brief biography of Terrell in that city directory called him the “Daniel Boone of our community.” Hard to argue with that. Ed Terrell was born in Kentucky early in the nineteenth century. As a young man he traveled across the South, buying and selling livestock and, like so many others, heading ever westward. By 1841 he was in Texas, trading with Native Americans. In November 1843 Terrell and fellow trader John P. Lusk of Arkansas camped at Live Oak Grove, which the 1877 city directory said was one and a half miles southwest of the courthouse. (Others have said the grove was where Traders Oak is today on Samuels Avenue.) The two men intended to open a trading post there. (The just-signed Treaty of Bird’s Fort and the 1844 Treaty of Tehuacana Creek promised the signatory tribes a line of white “trading houses” along the frontier.) Terrell and Lusk set about building a rudimentary store. They chopped down trees to make logs for walls, but to raise the logs they needed help. The nearest help was two white men “on White Rock” in Dallas County, which was only a bit more settled than Tarrant County. Think of that! The nearest help was thirty-five miles away. Make a list of everything Terrell and Rusk did not have. Start with lumber, nails, power tools, bricks, cement, a Home Depot ten minutes away, roads, GPS, AAA, ATMs, road maps, roadside parks, automobiles, Motel 6, Cracker Barrel, Buc-ee’s. etc. That was life on the frontier of north Texas in the 1840s.

Terrell and Lusk set out to fetch the two other white men. As the four men were returning to Live Oak Grove, they were captured by “a wandering band of wild Indians” near where today’s Mount Olivet Cemetery is. To escape their captivity, Terrell promised the chief that Terrell would go fetch some corn from white settlements, which the white traders would give to the captor Native Americans in trade for buffalo robes. The chief said the white men could go fetch corn if they promised to return within four days. To show his sincerity, Terrell shook hands with “as many as showed signs of friendship.” However, some of the Native Americans showed their “nay” vote with “very significant and angry grunts.”

Once freed, the white men promptly skedaddled and lit out for Parts Unknown. In fact, Terrell said he kept up a “brisk double quick” until he reached Bonham!

And it was in Bonham that Terrell met Lucinda Peveler. They were married in 1845.

The 1877 city directory said of Terrell: “As to the corn contract with the Indians, he frankly admits that it has not been fulfilled to this day.”

Reminiscing shortly before his death, Terrell said, “I did not return [to Tarrant County] until 1849, when the troops were stationed here . . . It was either a case of leaving Tarrant County . . . or losing our scalps, and when a man lost his hair in those days he generally lost something else. . . . In those days this country was infested with Indians, and herds of buffalo were all around us. There were more panthers in these parts than I have ever seen before or since; antelopes without number, wild turkeys in every tree—in fact, in those days this was God’s own country.”

By 1849 this area still had only trails, among them the Bird’s Fort, Grape Vine Spring, Eagle Ford, Preston, and Trading House trails. There was even a trail that led to California after the gold rush began.

Some local historians have said these trees at Cooper Street and 11th Avenue in the medical district are the remains of the Live Oak Grove where Terrell and Lusk intended to open their trading post.

Some local historians have said these trees at Cooper Street and 11th Avenue in the medical district are the remains of the Live Oak Grove where Terrell and Lusk intended to open their trading post.

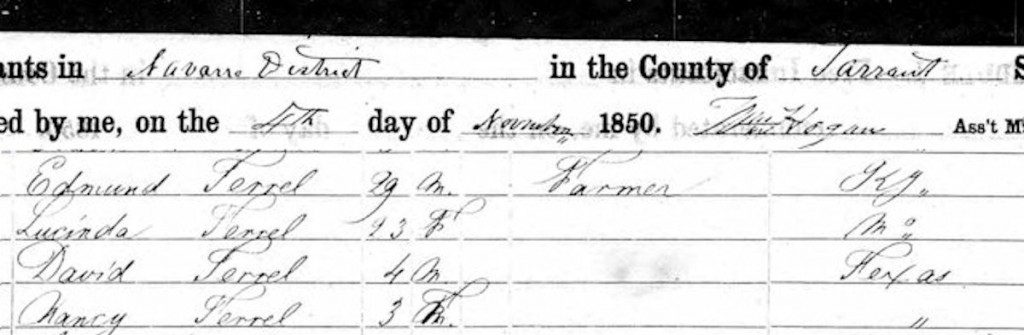

Terrell returned to this area in time to be included in Tarrant County’s first census in 1850. He supplied the fort with beef and corn.

Terrell returned to this area in time to be included in Tarrant County’s first census in 1850. He supplied the fort with beef and corn.

Even within Tarrant County Terrell gathered no moss. He lived at Birdville a while. The Birdville Historical Society says that in 1850 Terrell “offered his log cabin for an election polling site to choose the new county seat and to elect officers who would succeed the temporary persons appointed the preceding December 1849.”

Even within Tarrant County Terrell gathered no moss. He lived at Birdville a while. The Birdville Historical Society says that in 1850 Terrell “offered his log cabin for an election polling site to choose the new county seat and to elect officers who would succeed the temporary persons appointed the preceding December 1849.”

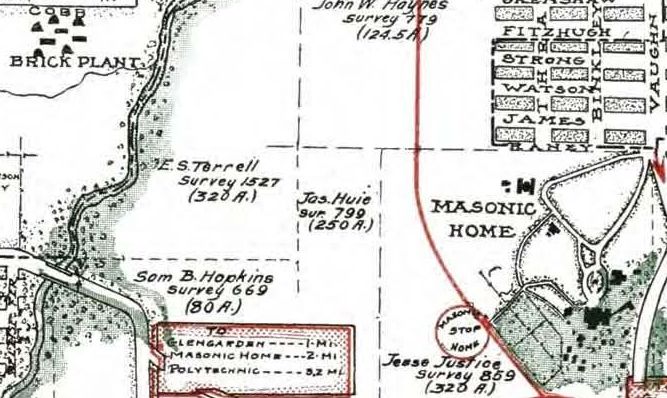

Terrell also farmed on land located between the future sites of the Cobb brothers’ brick plant and the Masonic Home southeast of the courthouse. He lived on land west of the courthouse that would later belong to Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt and become Trinity Park. (Map detail from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

In 1854, the city directory biography said, Terrell began dealing in land, “buying and selling and locating land certificates. . . . he located the grant made by the State of Texas to Elizabeth Crockett, consort of the famous David Crockett.” Elizabeth Crockett was given land grants in at least three counties—Tarrant, Parker, and Hood (where she lived). This detail of an 1895 Tarrant County map shows the E. Crockett survey north of Arlington Heights. Today River Crest Country Club is located on the Crockett survey. Terrell may have been given part of the Crockett survey in payment for locating it. (Map detail from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

In 1854, the city directory biography said, Terrell began dealing in land, “buying and selling and locating land certificates. . . . he located the grant made by the State of Texas to Elizabeth Crockett, consort of the famous David Crockett.” Elizabeth Crockett was given land grants in at least three counties—Tarrant, Parker, and Hood (where she lived). This detail of an 1895 Tarrant County map shows the E. Crockett survey north of Arlington Heights. Today River Crest Country Club is located on the Crockett survey. Terrell may have been given part of the Crockett survey in payment for locating it. (Map detail from Pete Charlton’s “1000+ Lost Antique Maps of Texas & the Southwest on DVD-ROM.”)

About 1856 Terrell bought and began operating the First and Last Chance Saloon in one of the fort’s abandoned log cabins on Weatherford Street near today’s courthouse.

Also in 1856, during the county election to choose (again) between Birdville and Fort Worth for the county seat, Terrell recalled, he and Sam Woody of Wise County brought in residents of Wise and Parker counties to vote for Fort Worth, swinging the election by twenty-six votes. (Woody’s son John recalled that the difference was only seven votes.)

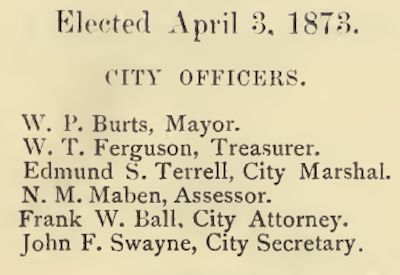

After Fort Worth incorporated in 1873, Terrell was elected the city’s first marshal. Clip is from Revised Ordinances of the City of Fort Worth, Texas.

After Fort Worth incorporated in 1873, Terrell was elected the city’s first marshal. Clip is from Revised Ordinances of the City of Fort Worth, Texas.

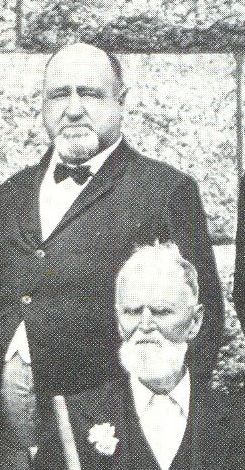

Terrell moved to Young County about 1885. Some years later Fort Worth photographer Charles Swartz took a photo of Fort Worth pioneers. Among them were Ed Terrell (bottom) and his cousin, attorney J. C. Terrell (top).

Terrell moved to Young County about 1885. Some years later Fort Worth photographer Charles Swartz took a photo of Fort Worth pioneers. Among them were Ed Terrell (bottom) and his cousin, attorney J. C. Terrell (top).

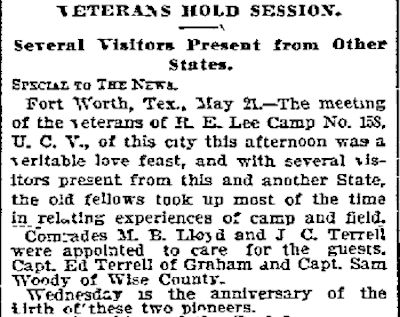

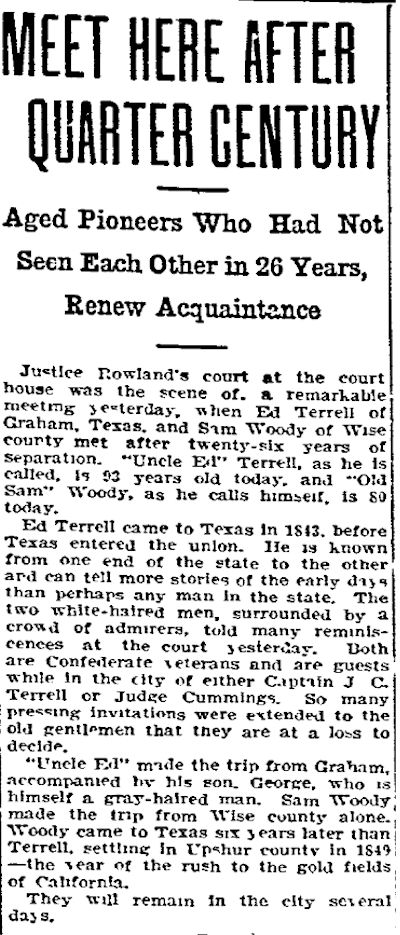

A half-century after the election of 1856, co-conspirators Terrell and Woody were reunited in Fort Worth at the courthouse and at a meeting of the Robert E. Lee Camp, a local Confederate veterans group. Clips are from the May 22 and 24, 1905 Telegram.

A half-century after the election of 1856, co-conspirators Terrell and Woody were reunited in Fort Worth at the courthouse and at a meeting of the Robert E. Lee Camp, a local Confederate veterans group. Clips are from the May 22 and 24, 1905 Telegram.

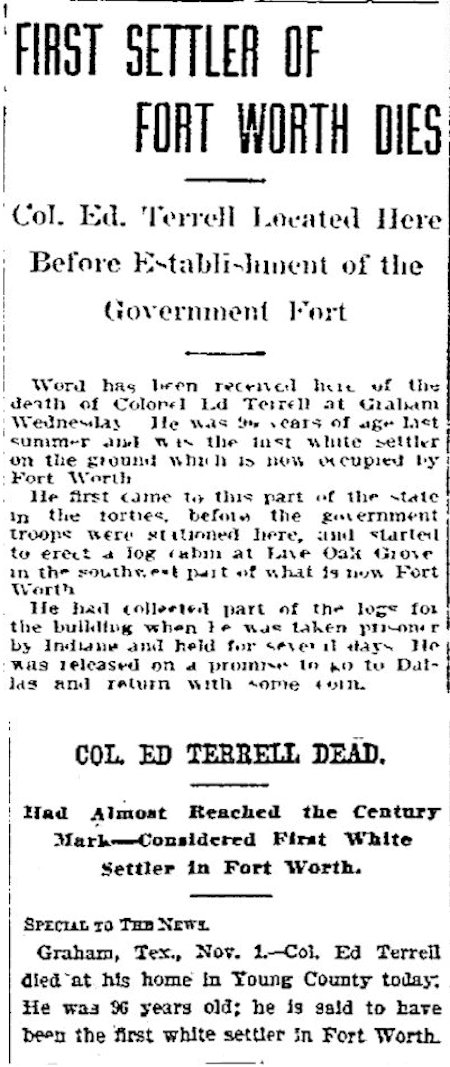

Edmund Stephenson Terrell, who was born early in the nineteenth century and came to Fort Worth before there was a Fort Worth and who lived into the twentieth century long enough to drive in an automobile, died on November 1, 1905. (Clips are from the November 2 Telegram and Dallas Morning News.)

Edmund Stephenson Terrell, who was born early in the nineteenth century and came to Fort Worth before there was a Fort Worth and who lived into the twentieth century long enough to drive in an automobile, died on November 1, 1905. (Clips are from the November 2 Telegram and Dallas Morning News.)

He is buried in True Cemetery in Young County. According to one obituary, Terrell was born in 1809. According to the 1850 census he was born in 1821. According to his tombstone he was born in 1812. (Photo detail from Find A Grave.)

He is buried in True Cemetery in Young County. According to one obituary, Terrell was born in 1809. According to the 1850 census he was born in 1821. According to his tombstone he was born in 1812. (Photo detail from Find A Grave.)

Great work, Mike. I would like to take this opportunity to thank the Comanche nation, the Kiowa, and the southern Cheyenne for letting the white man steal their land. I must insist, however, that the corn payment be made post haste. Chief White Ghost has appointed me to collect. Tell the chiselers to pay up.

Thanks, Running Bear. It’s a great episode, even though no two accounts of it are alike.

Wow!What a story! Love what you are doing and thanks for all the hours and love you put in it!

Thanks, Jo Ann. What a life he had. I like to picture him taking that ride in an automobile in 1905. He probably thought, “Now THIS is what I needed to get to White Rock back in forty-three!”