I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree.

Poet Joyce Kilmer wrote those leafy lines, whose sentiment no doubt was seconded by Samuel Oscar Blanc, the guy who founded Roto-Rooter.

Today is National Arbor Day. Let us celebrate trees and remind ourselves that sometimes history grows thereon:

For example, this live oak tree on Samuels Avenue bends low to the ground, as if weary. It’s entitled. This is Traders Oak, and it is Fort Worth’s family tree—been here since day one. And even before day one. In fact, Traders Oak probably was already middle aged in 1849 when Henry Clay Daggett (first of the three Daggett brothers to reach Fort Worth) and Archibald Leonard arrived to set up a trading post near the Army’s new fort.

Army regulations prohibited merchants from doing business within one mile of a fort, so the two traders built a log cabin at this big live oak and began Fort Worth’s first business. The location was perfect: soldiers for customers, soldiers for protection.

Native Americans also came to the store to trade pecans, furs, and buffalo hides. The tree became a center of community in those early days. A nearby cold spring provided water. After Tarrant County was created from sprawling Navarro County in 1849, the first county election was held at the tree in 1850. County officials were elected, and voters were asked to select the site of a county seat, which, the state decreed, would be named “Birdville” after Major Jonathan Bird, who had established Bird’s Fort near the Trinity River in 1841 in what is now north Arlington. A settlement ten miles west of Bird’s Fort won the election and became Birdville, the county seat. But in 1856 Fort Worth boosters talked the state legislature into calling a do-over second election for county seat and on election day lured voters to the polls by serving free whiskey. Depending on which historical account you read, Fort Worth won the Birdville-Fort Worth rematch by either seven or thirteen or (hic) twenty-six votes.

Shades of early Cowtown: After the Army vacated its Fort Worth in 1853, another Daggett brother, Ephraim, converted the fort’s stable into a lodging house in the nascent town of Fort Worth. But he soon sold the property to Lawrence Steel, who built on the site a two-story hotel, Steel’s Tavern. The hotel also had a stage coach office. Passengers could buy tickets and wait for the stage in the parlor or the sitting room. The first stage, carrying mail, arrived in July 1856. Today these three live oak, which provided shade first at the fort and then at Steel’s Tavern, shade pedestrians at Belknap and Houston streets. Just a few feet from the tree is a marker commemorating the town’s first school, established by John Peter Smith in 1853 in the “pest hospital” (for communicable diseases) of the abandoned fort.

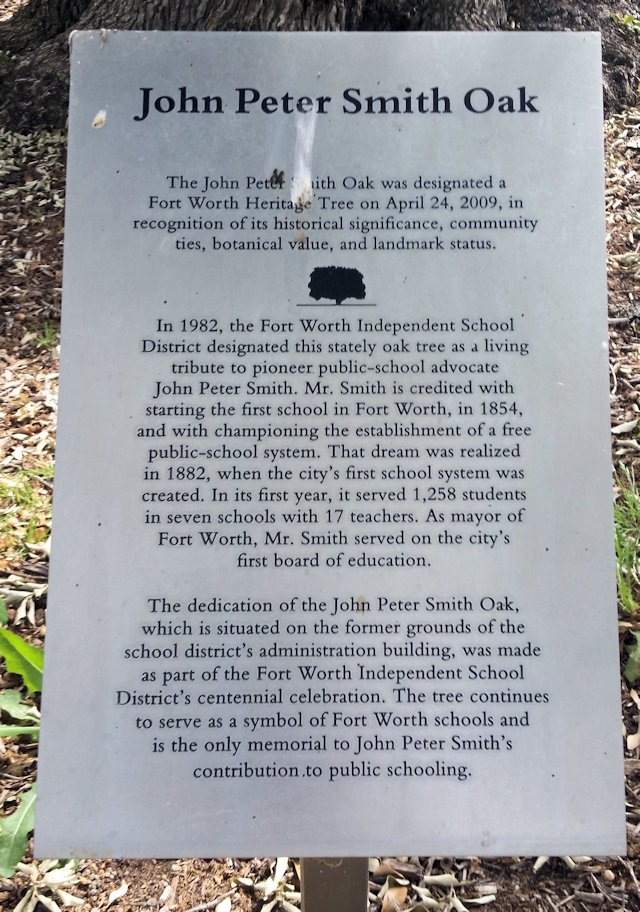

And in a parking lot three hundred feet south of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth stands the John Peter Smith Oak. Why is Smith honored with a tree at that particular location?

And in a parking lot three hundred feet south of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth stands the John Peter Smith Oak. Why is Smith honored with a tree at that particular location?

Because there is much history under the concrete of that museum parking lot. Smith, in addition to starting Fort Worth’s first school, was instrumental in founding the town’s public school system in 1882. And in 1955 that public school system built its administration building just south of that tree.

Because there is much history under the concrete of that museum parking lot. Smith, in addition to starting Fort Worth’s first school, was instrumental in founding the town’s public school system in 1882. And in 1955 that public school system built its administration building just south of that tree.

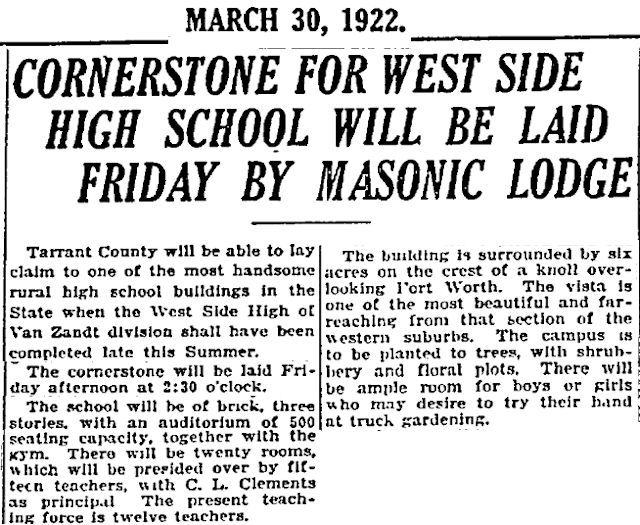

And just east of the John Peter Smith Oak was a building that some remember as Van Zandt Elementary School. (Photo from Billy W. Sills Center for Archives/FWISD.)

But the building, designed by Wiley Clarkson, began life in 1922 as West Side High School (also called “Van Zandt High School”). The school was in the Van Zandt school district (Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt had lived nearby and owned a huge amount of land in that area). But the Van Zandt school district used the building as a high school only briefly because later in 1922 the Fort Worth school district annexed the Van Zandt school district and designated West Side High School as “West Van Zandt Elementary School” (not to be confused with Van Zandt School of the Fifth Ward). The elementary school closed in 1964 because of low enrollment, and the building became an auxiliary of the main FWISD administration building. The Van Zandt building was torn down in 1986, the main administration building in the late 1990s.

But the building, designed by Wiley Clarkson, began life in 1922 as West Side High School (also called “Van Zandt High School”). The school was in the Van Zandt school district (Major Khleber Miller Van Zandt had lived nearby and owned a huge amount of land in that area). But the Van Zandt school district used the building as a high school only briefly because later in 1922 the Fort Worth school district annexed the Van Zandt school district and designated West Side High School as “West Van Zandt Elementary School” (not to be confused with Van Zandt School of the Fifth Ward). The elementary school closed in 1964 because of low enrollment, and the building became an auxiliary of the main FWISD administration building. The Van Zandt building was torn down in 1986, the main administration building in the late 1990s.

Greenwood’s first burial was gold: Captain Charles Turner was one of Colonel Middleton Tate Johnson’s Texas Rangers. In 1849 Turner accompanied Johnson and Major Ripley Arnold as they scouted for a suitable location to establish the U.S. Army’s Fort Worth. Later Turner owned a farm where Greenwood Cemetery (1909) now is. When the Civil War began, the Confederacy required its citizens to exchange their gold for Confederate notes. Turner had a better idea: With the help of a trusted slave, Turner buried his gold—believed to have been thousands of dollars’ worth—under a live oak tree on his farm. After the war Turner dug up the gold and used it to help revive Fort Worth’s struggling economy and to help the city pay debts to creditors in the North. Today the Turner Oak stands in a traffic circle in the cemetery.

The traders took a powder: In 1843 Ed Terrell of Kentucky was one of the first white settlers in what would become Tarrant County. “There were more panthers in these parts than I have ever seen before or since; antelopes without number, wild turkeys in every tree—in fact, in those days this was God’s own country,” Terrell recalled years later. It was also Native American country. In 1844 Terrell and trapper John Lusk, from Arkansas, traded with local Native Americans—beads and trinkets for buffalo robes and other pelts. Planning to build a trading post on the Trinity, the two men selected a site in a live oak grove where Sports Rehab Specialists now stands at Cooper Street and 11th Avenue. They cut down trees and trimmed the logs. But they needed help lifting the logs into place. So, they headed east to fetch two other traders about thirty miles away in Dallas County. But along the way Native Americans captured Terrell and Lusk. After about a year in captivity, the two men tricked the Native Americans: Terrell, who baked biscuits for the Native Americans, told them that he was out of flour and needed to go get more. As the story goes, the Native Americans freed the two men after the two men promised to return.

Terrell hightailed it out of Tarrant County and didn’t return until 1849 after the fort was established. He operated the First and Last Chance Saloon in a log cabin near the courthouse and was elected the city’s first marshal in 1873.

Yes, history grows on trees. And sometimes so do bicycles: Years ago Grand Avenue homeowner George Hilton started his bike tree. (Update: The tree is still there, but the bicycles are gone.)

Not to be confused with Steel’s trees are these steel trees. This sculpture by Roxy Paine at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth is entitled Conjoined.

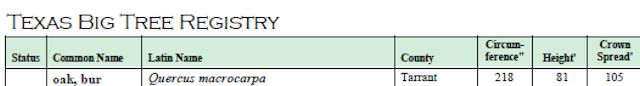

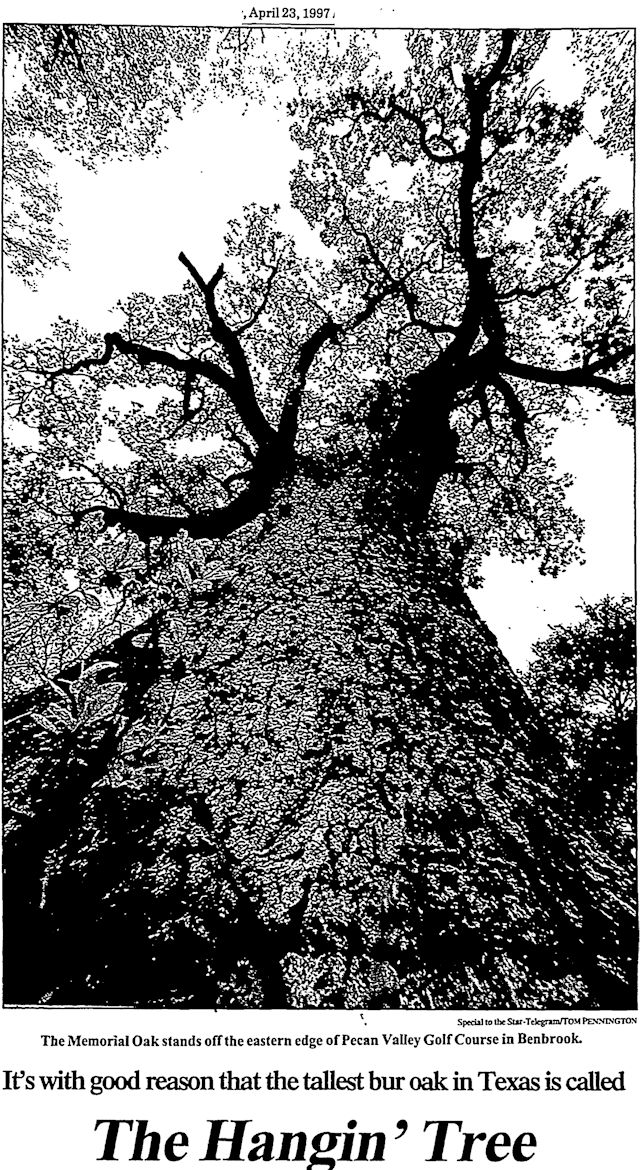

And just for good measure, there’s the Memorial Oak, tucked away near the second fairway of Pecan Valley Golf Course in southwest Fort Worth. It is the Texas state champion bur oak.

And just for good measure, there’s the Memorial Oak, tucked away near the second fairway of Pecan Valley Golf Course in southwest Fort Worth. It is the Texas state champion bur oak.

The Memorial Oak is eighty-one feet high, nineteen feet in circumference (almost six feet in diameter). (You knew that Texas would have an official registry for biggest trees, didn’t you?) The tree is thought to be about four hundred years old. Comanche and Kiowa tribes considered the tree to be sacred and conducted ceremonies under it.

The Memorial Oak is eighty-one feet high, nineteen feet in circumference (almost six feet in diameter). (You knew that Texas would have an official registry for biggest trees, didn’t you?) The tree is thought to be about four hundred years old. Comanche and Kiowa tribes considered the tree to be sacred and conducted ceremonies under it.

But the Memorial Oak holds the record for bur oaks in Texas no thanks to some vandals who in 2011 took an ax to the tree. A scar can be seen above the bicycle.

But the Memorial Oak holds the record for bur oaks in Texas no thanks to some vandals who in 2011 took an ax to the tree. A scar can be seen above the bicycle.

Why is the big oak called the “Memorial Oak”? The Army Corps of Engineers and Texas Forest Service don’t have an answer for that. But at one time the tree had another title: the biggest hanging tree in north Texas. And the tree is said to have earned that title in 1884:

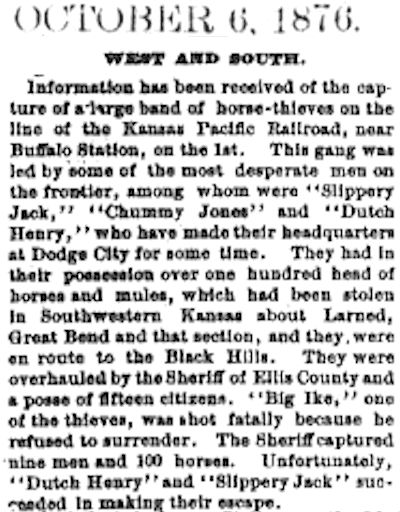

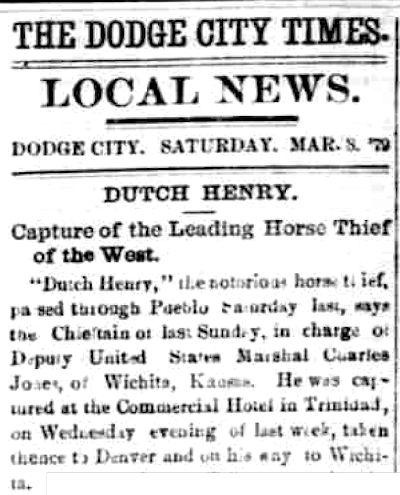

Henry Borne, known as “Dutch Henry,” had briefly served as a scout for General Custer before quitting and turning to stealing horses in Kansas, Texas, New Mexico, Arkansas, and Colorado. Dutch Henry specialized in stealing Native American ponies and government mules. According to one legend, he once sold a sheriff the sheriff’s own stolen horse. He even opened a sales stable in Dodge City, Kansas to sell his stolen property.

Dutch Henry was often captured and just as often escaped. But in 1884 he and two members of his gang were wanted in five states when ranchers southwest of Fort Worth heard that Dutch Henry and colleagues were camped nearby. The ranchers set a trap: They baited a corral with horses and waited in ambush. When the outlaws attempted to steal the corraled horses, the ranchers surprised the outlaws, who were outnumbered four to one. The outlaws threw up their hands in surrender. Sam Owens, one of the ranchers, wrote in 1905: “All our men were hollering for ‘immediate justice.’ A delay for a trial and all that lawyer stuff seemed out of place. . . . We headed down Mary’s Creek toward ‘the Big Daddy of hangin’ trees’—that big old bur oak down south on the Clear Fork. We had quite a chore to throw those three ropes way up to the lowest limb. It was just turning twilight and I got a funny feeling in my stomach as I saw those three silent bodies hangin’ there, swayin’ back and forth in the breeze.”

Dutch Henry was often captured and just as often escaped. But in 1884 he and two members of his gang were wanted in five states when ranchers southwest of Fort Worth heard that Dutch Henry and colleagues were camped nearby. The ranchers set a trap: They baited a corral with horses and waited in ambush. When the outlaws attempted to steal the corraled horses, the ranchers surprised the outlaws, who were outnumbered four to one. The outlaws threw up their hands in surrender. Sam Owens, one of the ranchers, wrote in 1905: “All our men were hollering for ‘immediate justice.’ A delay for a trial and all that lawyer stuff seemed out of place. . . . We headed down Mary’s Creek toward ‘the Big Daddy of hangin’ trees’—that big old bur oak down south on the Clear Fork. We had quite a chore to throw those three ropes way up to the lowest limb. It was just turning twilight and I got a funny feeling in my stomach as I saw those three silent bodies hangin’ there, swayin’ back and forth in the breeze.”

(Another source claims Dutch Henry died of pneumonia in 1921.)

Was this pecan tree in the median of Bellaire Drive South a trail marker tree formed by Native Americans? Some residents of the Overton Woods neighborhood believe so. The website Heritage Trees of Fort Worth, presented by the Forestry Section of Fort Worth Parks and Community Services Department, says: “These nomads would follow large herds of animals and are known to have tied the tops of saplings to the ground in locations near crucial resources and along important routes. As the trees matured, the bend would stay in place and a navigation landmark was created. This pecan points to the nearby Trinity River and is believed to have guided the Native Americans to a reliable water source.” (Thanks to Paul Valentine for the tip.)

Lastly, let us remember five trees that no longer stand or at least can’t be identified, two with a negative story to tell, three with a positive story to tell:

1. The tree from which William H. Crawford and Anthony Bewley were hanged in 1860.

2. The tree from which Tom Vickery was hanged in 1920 and Fred Rouse was hanged in 1921.

3. The tree planted by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1905 at the Carnegie Public Library. (According to historian Dr. Richard F. Selcer, the tree died, as did a replacement supplied by Roosevelt.)

4. The tree planted planted by the Polytechnic College class of 1906.

5. Finally, let us remember a tree that had high hopes (“high apple pie, in the sky hopes”). For a few years a little tree lived life on its own terms and against great odds on the roof of the eight-story Texas & Pacific freight terminal. Perhaps a passing bird had dropped a seed into a crevasse filled with dirt accumulated over the years. The little tree was barely visible from the ground. Alas, the last time I checked, the tree could not be seen from the street or on a Google satellite view.

I played under that John Peter Smith oak tree. I attended West Van Zandt elementary school 1945-1949. I had started the 1st grade in 1943 at Carrol Peak elementary. That tree was one of many big beautiful trees in our playground that went all the way to Arch Adams street on the West. My family lived behind Montgomery Wards on Wingate street. All of us kids in that sub-division walked to West Van Zandt. Now retired, I was at one time “Charlie Brown” a deejay on WBAP country gold. I live in far north Fort Worth, the so-called Alliance corridor.

I’ve happened upon your site as I was looking for information about Lake Erie. After a few more rabbit holes, I’m wondering if you have anything about the development of the Botanic Garden or Rock Springs Park?

Thank you for visiting the site. Unfortunately the author, Mike Nichols, passed away and we are working on how best to preserve this informative site.

I am familiar with the oak that was part of the Van Zandt elementary school property. I started school there in 1949 from first to sixth grade. We kids lined up just like in the photo and marched into the school to our classrooms. I’m 78 now. But I have another question I’d like to research. Yesterday Richard Selcer wrote in the ST about Riverside and Ray Sharpe, local piano player who had a dancehall called Linda Lou’s. I’d like to know if he’s still alive. I know his one big hit was Linda Lou, and I am not that Linda Lou, but I did work for Al’s Formal Wear owned by Al Sankary, and he tailored the bands tuxedos. Mr. Sankary was married to Yetta Haller who had the tailor business, and she died. He later renamed the business and was very successful. I worked there about 4 years. I’d like you to follow up on this if you are interested.

Edward Ray Sharpe, born in Fort Worth in 1938, apparently is still alive.

The Turner Oak used to be the Greenwood logo before the 4 horses were placed at the entrance of Greenwood and then they became the Greenwood logo!

Mike…its Clara Ruddell (Holmes) from the Tarrant County Historical Commission. We have funding from the Fash Foundation Fort Worth to place a marker at the Steel Tavern Oaks. Marker has been ordered and I expect we will plant it about February of 2020.

Would you like to meet us perhaps at the tree and we could share the marker text with you and keep you in the loop for the dedication.

Thanks for the heads-up, Clara. And congratulations to that grand old tree, which has seen (and survived) so much change in its long life. Do let me know when the marker is up, and I will get a photo to update my post.

Thank you, Mike for the photo of West Van Zandt. I spent the first grade there. We took our class photo on the steps just above the sidewalk. All of those childhood scenes have been lost for years. You’ve succeeded in making this tough old gal a bit weepy eyed.

My first week there I got in trouble for destroying my school supplies. The big fat, flat sided crayons were hard for me to handle so I ripped the paper off all of them and broke them in half. That way I was able to use the sides. My teacher asked me how I would know what color I had with the paper gone. I told her it was ok because I couldn’t read.

Great anecdote about the crayons. Thinking outside the Crayola box. I wish the school district had preserved more of our old schools, my own D. McRae included.

Good work, Mike. I’m surprised any trees survive at all, what with greedy builders wanting to bulldoze anything in the way. Mexicans that hate trees, they will cut a tree in a heartbeat. Monsters hide in them, after all. As for the hanging trees, we can always build a gallows or just use the one in the courthouse. Keep the bike rolling but away from the bike tree.

Thanks, Earl. Takes just a minute to cut one down but a lifetime to grow a new one.

Wow! I had no idea!