This stately building of 1886 was located at Main and Lancaster streets (photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library):

(A spudder is a well-drilling rig or an operator of such a rig.)

(A spudder is a well-drilling rig or an operator of such a rig.)

This nondescript building of the late 1950s is located at 2910 Shotts Street east of Greenwood Cemetery:

What connection could there be between these two buildings? And, more important, what connection could there be between these two buildings and (1) a man born in Scotland in 1842, (2) Fort Worth’s first violent labor dispute in 1886, and (3) a grim first-person account of segregation in the South in the 1950s?

What connection could there be between these two buildings? And, more important, what connection could there be between these two buildings and (1) a man born in Scotland in 1842, (2) Fort Worth’s first violent labor dispute in 1886, and (3) a grim first-person account of segregation in the South in the 1950s?

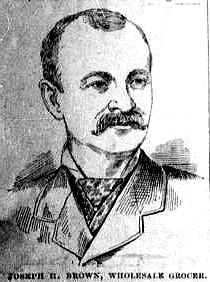

Our first connection is Joseph H. Brown. Brown was born in Dundee, Scotland in 1842. In 1859, at age seventeen, he came to America. In Chicago he worked a few years as a clerk in a cigar and tobacco house. Then he went into business with a partner and later by himself in Kansas City. When his business in Kansas City failed, he moved to Fort Worth in 1872 and opened a small retail grocery store on the courthouse square. In 1872, the Star-Telegram later wrote, “only three rutted wagon roads, impassable in bad weather, connected Fort Worth with the outside world.” Brown’s inventory was hauled to town along those rutted wagon roads by a string of mules.

Our first connection is Joseph H. Brown. Brown was born in Dundee, Scotland in 1842. In 1859, at age seventeen, he came to America. In Chicago he worked a few years as a clerk in a cigar and tobacco house. Then he went into business with a partner and later by himself in Kansas City. When his business in Kansas City failed, he moved to Fort Worth in 1872 and opened a small retail grocery store on the courthouse square. In 1872, the Star-Telegram later wrote, “only three rutted wagon roads, impassable in bad weather, connected Fort Worth with the outside world.” Brown’s inventory was hauled to town along those rutted wagon roads by a string of mules.

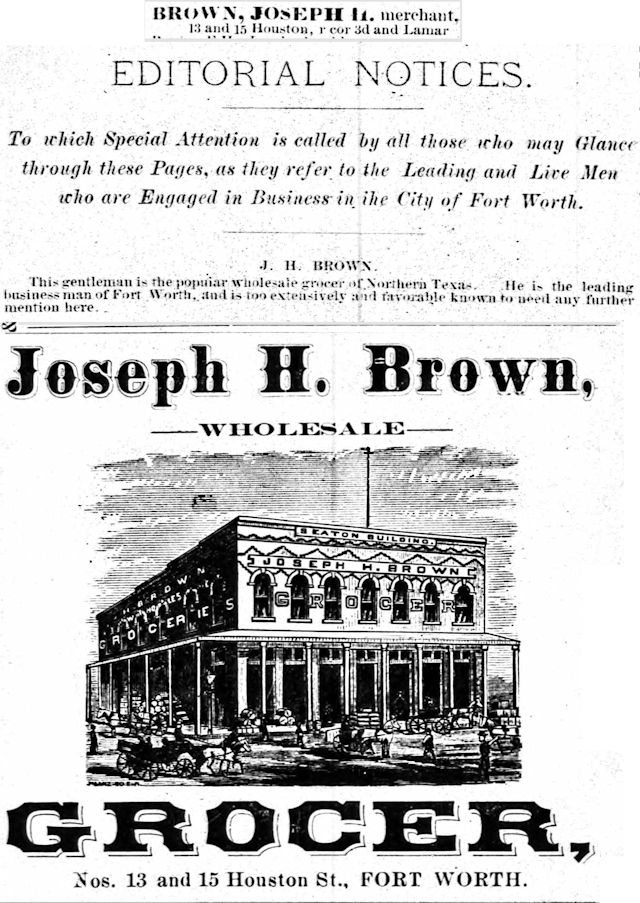

But fast-forward four years. Everything changed in 1876—for Brown and for Fort Worth. Brown, B. B. Paddock would later write, was one of the civic leaders who “contributed of their time and money without stint” to bring the railroad to town. Now Brown did not need to depend on those three rutted wagon roads. With the railroad he could buy groceries in larger quantity and get them delivered faster and more dependably. He began buying groceries by the train carload, receiving a volume discount from both his vendors and the railroad. And he began selling to retail grocers (Fort Worth alone had fifty-four by 1885). Thus, Joseph H. Brown became Fort Worth’s first wholesaler. His sales territory covered most of Texas. Soon he would have annual sales of $1.8 million ($46 million today).

But fast-forward four years. Everything changed in 1876—for Brown and for Fort Worth. Brown, B. B. Paddock would later write, was one of the civic leaders who “contributed of their time and money without stint” to bring the railroad to town. Now Brown did not need to depend on those three rutted wagon roads. With the railroad he could buy groceries in larger quantity and get them delivered faster and more dependably. He began buying groceries by the train carload, receiving a volume discount from both his vendors and the railroad. And he began selling to retail grocers (Fort Worth alone had fifty-four by 1885). Thus, Joseph H. Brown became Fort Worth’s first wholesaler. His sales territory covered most of Texas. Soon he would have annual sales of $1.8 million ($46 million today).

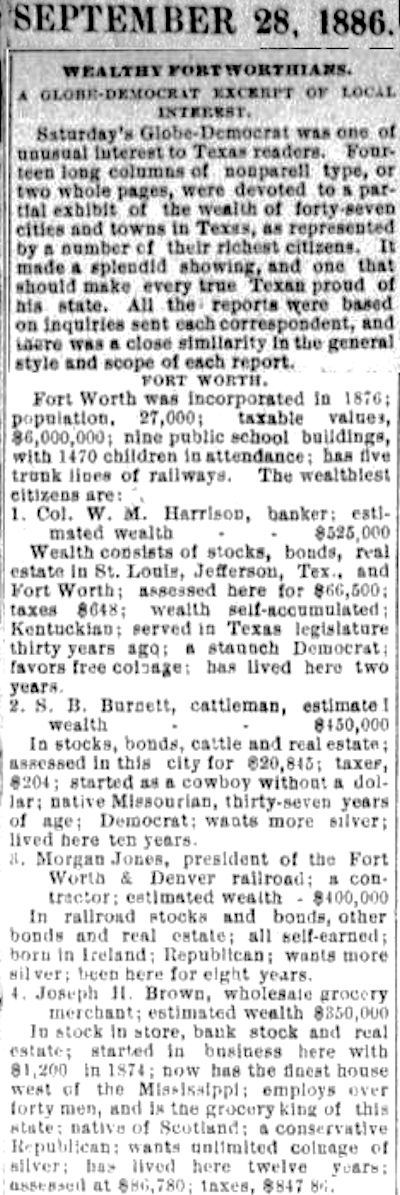

Sales numbers like that by 1886 had made Joseph H. Brown a wealthy man. In fact, when the St. Louis Globe-Democrat listed the richest people in Texas, Brown was ranked fourth in Fort Worth, with “the finest house west of the Mississippi.” The wealth of “the grocery king of the state” was estimated at $350,000 ($9.3 million today). (Fort Worth incorporated in 1873, not 1876, and that population count of 27,000 is a bit high.)

Sales numbers like that by 1886 had made Joseph H. Brown a wealthy man. In fact, when the St. Louis Globe-Democrat listed the richest people in Texas, Brown was ranked fourth in Fort Worth, with “the finest house west of the Mississippi.” The wealth of “the grocery king of the state” was estimated at $350,000 ($9.3 million today). (Fort Worth incorporated in 1873, not 1876, and that population count of 27,000 is a bit high.)

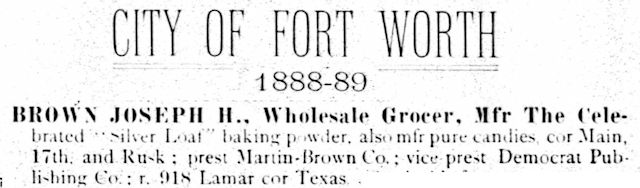

Like many affluent early civic leaders, Brown was diversified. He was a director of the Fort Worth & Rio Grande railroad, a partner in a flour mill, and vice president of the Democrat Publishing Company, publisher of the Fort Worth Gazette.

Like many affluent early civic leaders, Brown was diversified. He was a director of the Fort Worth & Rio Grande railroad, a partner in a flour mill, and vice president of the Democrat Publishing Company, publisher of the Fort Worth Gazette.

He also manufactured (and sold) Silver Loaf baking powder, candies, bluing, extract, and vinegar.

He also manufactured (and sold) Silver Loaf baking powder, candies, bluing, extract, and vinegar.

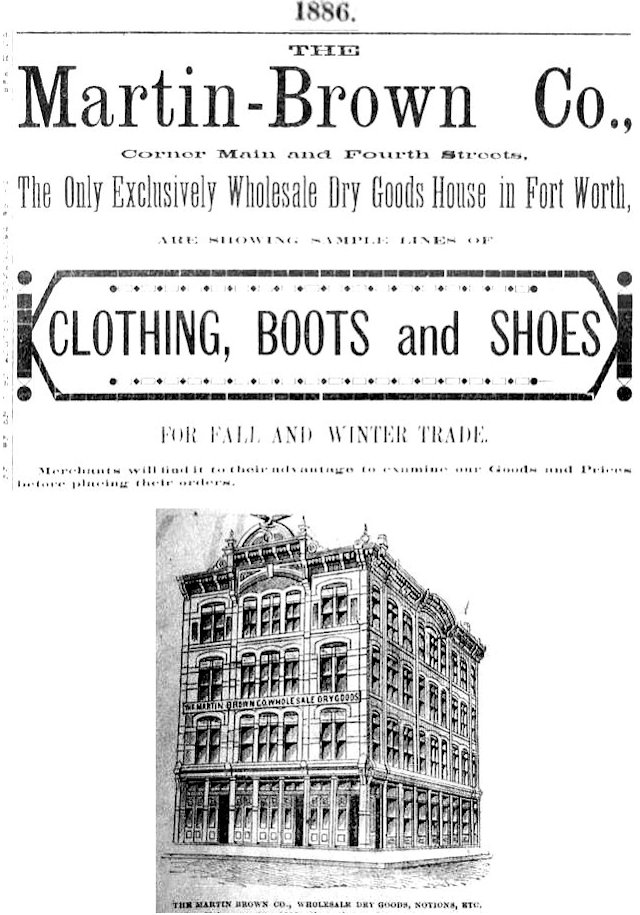

And by 1886 Brown had branched out into wholesale dry goods with Sidney Martin. The Martin-Brown business was located at Main and 4th streets.

And by 1886 Brown had branched out into wholesale dry goods with Sidney Martin. The Martin-Brown business was located at Main and 4th streets.

Yes, by 1886 Brown had become the “merchant prince of northwest Texas,” the Sam Walton of his time, buying in volume, underpricing his competition. Paddock in his 1922 history of Texas wrote that Brown’s was the “largest wholesale grocery establishment south of St. Louis.”

Yes, by 1886 Brown had become the “merchant prince of northwest Texas,” the Sam Walton of his time, buying in volume, underpricing his competition. Paddock in his 1922 history of Texas wrote that Brown’s was the “largest wholesale grocery establishment south of St. Louis.”

Brown would advertise two carloads of raisins one week and five carloads of apples the next. Or three thousand bags of coffee. Or lemons or buckwheat flour.

By 1886 Brown was booming. And so was Fort Worth. Cowtown was shaking off the wild and the woolly of its frontier past (even though Cowtown had at least one more gunfight in its future). In fact, by 1886 the Gazette rather grandly referred to Cowtown as “the Chicago of the Southwest”—sixteen years before the packing plants would make such a title more credible. A population of less than one thousand before arrival of the railroad in 1876 was, by 1886, well on its way to Fort Worth’s 1890 census count of 23,076. In 1886, the city directory boasted, Fort Worth had an area of nine square miles. It was served by five trunk-line railroads, had nine miles of streetcar track, seven miles of paved (with stone) streets, twelve miles of water pipe, and ten miles of sewer pipe by which “all offal and refuse substances . . . are discharged into the river a mile below the city.” Fort Worth had 600 telephone subscribers, 116 electric street lamps, 1 opera house, and 18 churches (fourteen white, four “colored”).

But Fort Worth also had growing pains: 1886 was the year Fort Worth, with those five railroads, experienced its first big-city labor trouble when a strike by railroad workers turned violent on April 3 at the Battle of Buttermilk Junction.

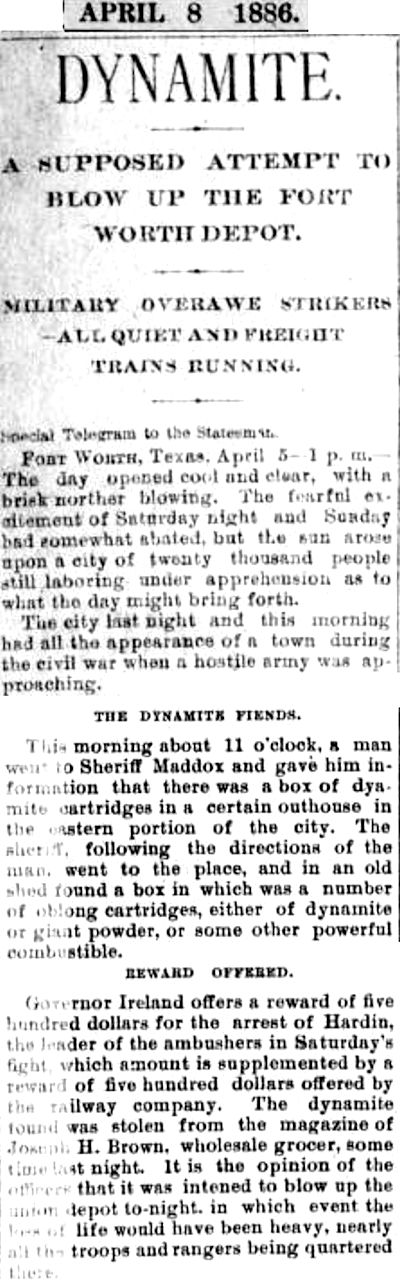

After the Battle of Buttermilk Junction, as the smoke cleared and lawmen searched for ambush leader John R. Hardin, Texas Rangers and state militia patrolled Cowtown. On April 5 a stash of dynamite was found on the east side of downtown. The dynamite had been stolen from the magazine of wholesale grocer Joseph H. Brown. Perhaps a calamity had been averted: Lawmen feared that someone had intended to use the dynamite to blow up the nearby Union Depot, where the Rangers and militia were quartered.

After the Battle of Buttermilk Junction, as the smoke cleared and lawmen searched for ambush leader John R. Hardin, Texas Rangers and state militia patrolled Cowtown. On April 5 a stash of dynamite was found on the east side of downtown. The dynamite had been stolen from the magazine of wholesale grocer Joseph H. Brown. Perhaps a calamity had been averted: Lawmen feared that someone had intended to use the dynamite to blow up the nearby Union Depot, where the Rangers and militia were quartered.

The Union Depot was spared, calm returned to Cowtown, the railroad strike ended, and Fort Worth and Joseph H. Brown’s business resumed their growth. And that brings us to our second connection: By 1886 Brown needed a bigger building for his empire of apples and raisins and coffee beans.

So, he built one. A big one.

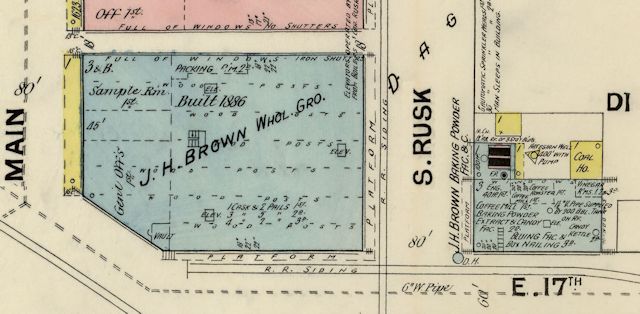

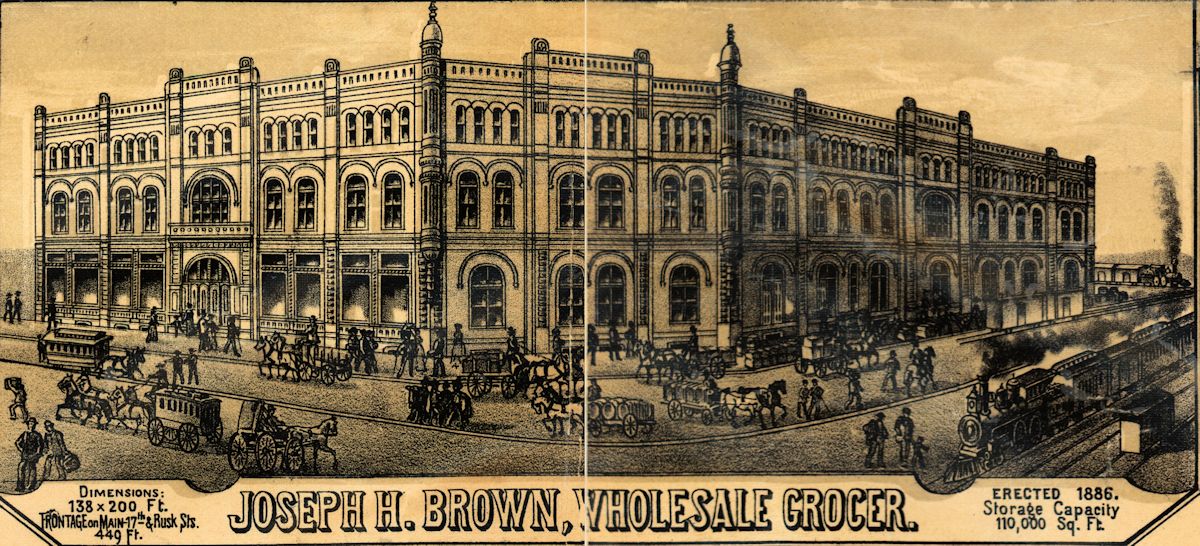

In fact, with three floors and a basement and a footprint of 138 by 200 feet, Brown’s building for years was one of the largest in town. The building stretched from Main Street east to Rusk (Commerce) Street with a south side along East 17th Street. A small factory behind the main building roasted and milled coffee beans and made Silver Loaf baking powder, candies, bluing, extract, and vinegar. Santa Fe and Missouri Pacific railroad sidings on East 17th and Rusk streets allowed Brown to send and receive goods directly. The main building was faced with stone from Palo Pinto and Wise counties, had an elevator, and probably had a wooden, not steel, frame. Cost: $105,000 ($2.7 million today). The Gazette proclaimed that Brown’s building was the “largest and most costly building in north Texas” and predicted that it would for years “remain a monument to his commercial greatness.”

In fact, with three floors and a basement and a footprint of 138 by 200 feet, Brown’s building for years was one of the largest in town. The building stretched from Main Street east to Rusk (Commerce) Street with a south side along East 17th Street. A small factory behind the main building roasted and milled coffee beans and made Silver Loaf baking powder, candies, bluing, extract, and vinegar. Santa Fe and Missouri Pacific railroad sidings on East 17th and Rusk streets allowed Brown to send and receive goods directly. The main building was faced with stone from Palo Pinto and Wise counties, had an elevator, and probably had a wooden, not steel, frame. Cost: $105,000 ($2.7 million today). The Gazette proclaimed that Brown’s building was the “largest and most costly building in north Texas” and predicted that it would for years “remain a monument to his commercial greatness.”

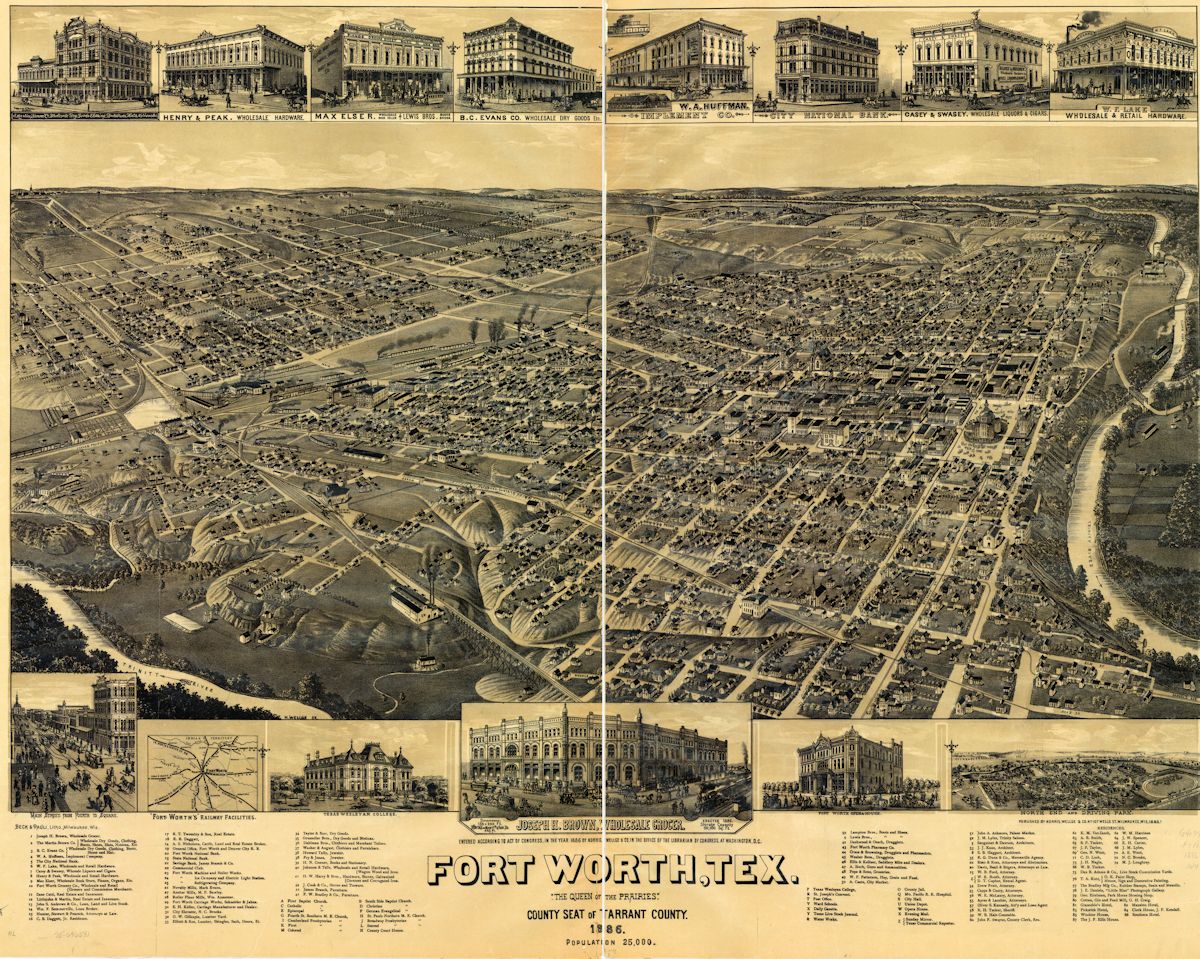

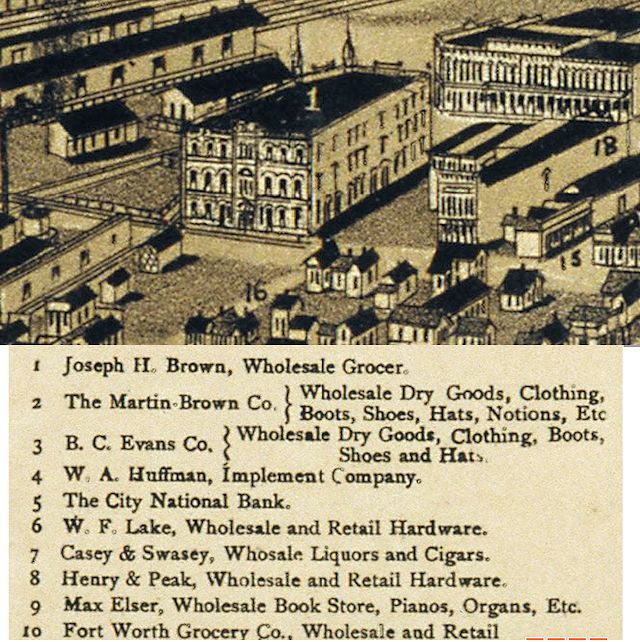

One of the most interesting relics of 1886 Fort Worth is Henry Wellge’s bird’s-eye-view map. (The map is too large and detailed to display well in this space, but Amon Carter Museum has a zoomable version.)

One of the most interesting relics of 1886 Fort Worth is Henry Wellge’s bird’s-eye-view map. (The map is too large and detailed to display well in this space, but Amon Carter Museum has a zoomable version.)

The Wellge map includes, in addition to its aerial perspective of the city, illustrations of some major buildings, such as those of W. A. Huffman, Max Elser, and B. C. Evans, the Opera House, the Driving Park, and Texas Wesleyan College.

But the building most prominently displayed is Brown’s. The illustration is a tableau of life in Fort Worth in 1886: steam locomotives, horse-drawn wagons and streetcars.

But the building most prominently displayed is Brown’s. The illustration is a tableau of life in Fort Worth in 1886: steam locomotives, horse-drawn wagons and streetcars.

I suspect that because the Brown building was new, he paid the mapmaker to have his building (1) prominently displayed and (2) listed first in the legend that identifies buildings shown on the map.

I suspect that because the Brown building was new, he paid the mapmaker to have his building (1) prominently displayed and (2) listed first in the legend that identifies buildings shown on the map.

Fast-forward four years. In 1890 Sidney Martin and Joseph H. Brown built a new home for their dry goods partnership on Main Street at 8th. At six stories it was among Fort Worth’s first “skyscrapers.” (In 1901 Joseph G. Wheat would buy the building, rename it for himself, and add a rooftop garden restaurant. The rooftop restaurant would later be converted into a seventh story for office space. The Wheat Building would be demolished in 1940.)

Fast-forward four years. In 1890 Sidney Martin and Joseph H. Brown built a new home for their dry goods partnership on Main Street at 8th. At six stories it was among Fort Worth’s first “skyscrapers.” (In 1901 Joseph G. Wheat would buy the building, rename it for himself, and add a rooftop garden restaurant. The rooftop restaurant would later be converted into a seventh story for office space. The Wheat Building would be demolished in 1940.)

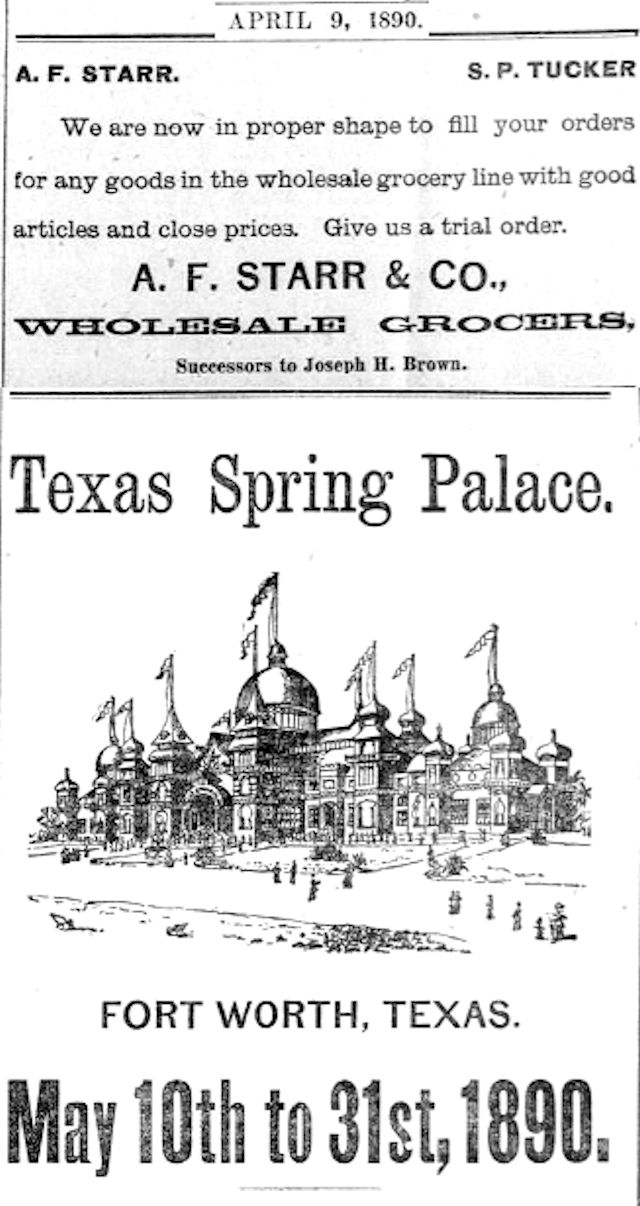

But by 1890 Joseph H. Brown, although only forty-eight years old, was in failing health. His business and 1886 building were taken over by A. F. Starr. (At the time, Fort Worth was preparing for the second season of its Spring Palace exhibition. It would not end well.)

But by 1890 Joseph H. Brown, although only forty-eight years old, was in failing health. His business and 1886 building were taken over by A. F. Starr. (At the time, Fort Worth was preparing for the second season of its Spring Palace exhibition. It would not end well.)

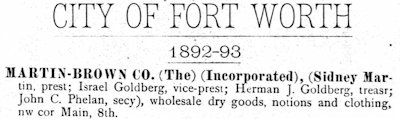

Likewise, Sidney Martin replaced Brown as president of Martin-Brown.

Likewise, Sidney Martin replaced Brown as president of Martin-Brown.

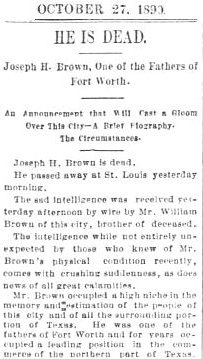

Later that year, just four years after Joseph H. Brown built the “monument to his commercial greatness,” he died. The Gazette eulogized him as “one of the fathers of Fort Worth.”

Later that year, just four years after Joseph H. Brown built the “monument to his commercial greatness,” he died. The Gazette eulogized him as “one of the fathers of Fort Worth.”

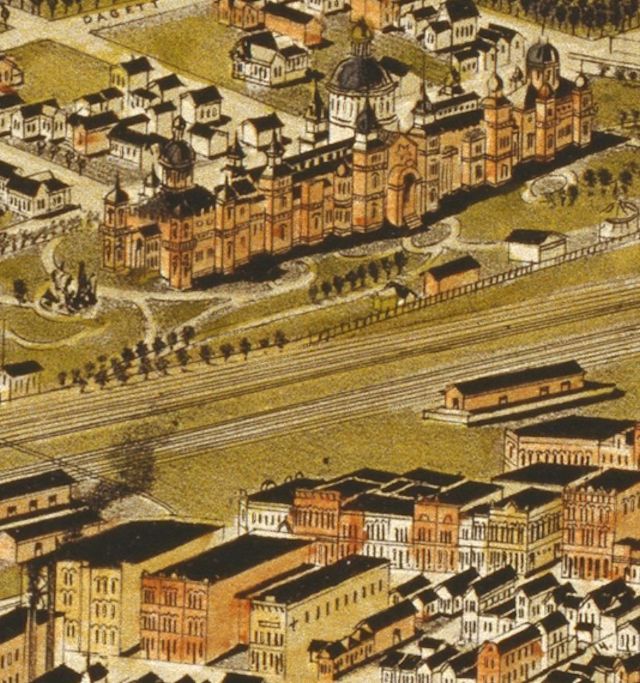

This 1891 bird’s-eye-view map by American Publishing Company shows the Brown building in the lower left. (By 1891 the Spring Palace was a sad anachronism.)

This 1891 bird’s-eye-view map by American Publishing Company shows the Brown building in the lower left. (By 1891 the Spring Palace was a sad anachronism.)

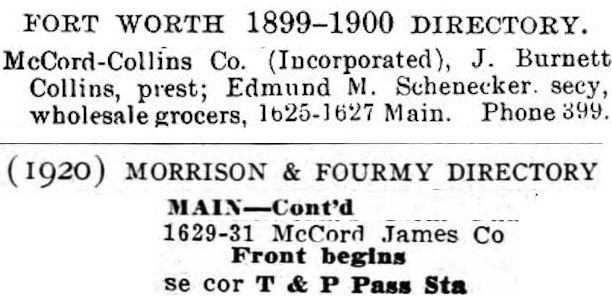

The wholesale grocer McCord-Collins Company took over the Brown building in 1898.

The wholesale grocer McCord-Collins Company took over the Brown building in 1898.

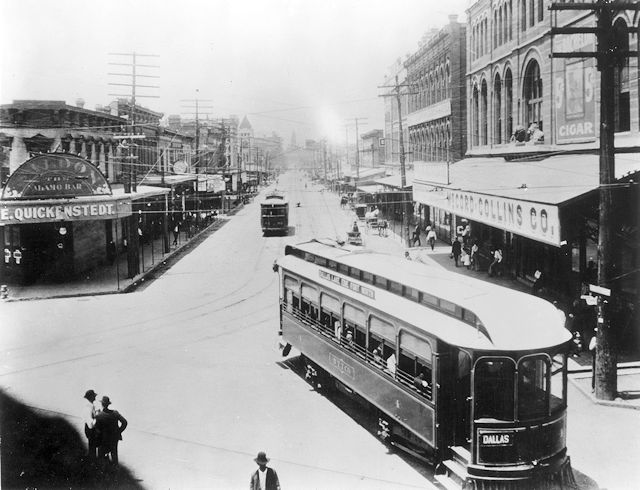

By the twentieth century Main Street was a cobweb of electricity, telephone, streetcar, and interurban wires. In this photo, sometime between 1902 and 1905 an interurban car bound for Dallas passes Brown’s building at Main and Lancaster. Across the street was Ernest Quickenstedt’s Alamo Bar. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

In this 1904 Charles Swartz photo of the Texas & Pacific depot fire, part of the Brown building can be seen to the left of the Al Hayne memorial. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

In this 1904 Charles Swartz photo of the Texas & Pacific depot fire, part of the Brown building can be seen to the left of the Al Hayne memorial. (Photo from University of Texas at Arlington Library.)

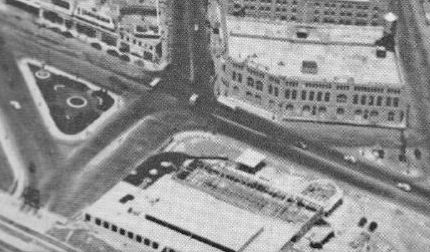

This 1928 aerial photo shows the Brown building and factory, the 1899 Texas & Pacific depot, and the Al Hayne memorial. Just north of the Brown building is the 1925 Monnig warehouse, designed by Sanguinet and Staats. Today the Monnig building is Water Gardens Place. Note the tiny building shaped like a slice of pizza in the triangle formed by Lancaster, Commerce, and East 17th streets.

This 1928 aerial photo shows the Brown building and factory, the 1899 Texas & Pacific depot, and the Al Hayne memorial. Just north of the Brown building is the 1925 Monnig warehouse, designed by Sanguinet and Staats. Today the Monnig building is Water Gardens Place. Note the tiny building shaped like a slice of pizza in the triangle formed by Lancaster, Commerce, and East 17th streets.

In 1928 the next occupant of Brown’s 1886 building became Fort Worth Well Machinery & Supply Company, which had grown out of Fort Worth Machine and Foundry, established about 1902.

In 1928 the next occupant of Brown’s 1886 building became Fort Worth Well Machinery & Supply Company, which had grown out of Fort Worth Machine and Foundry, established about 1902.

By 1940 the depot was gone, and the Brown building had a new neighbor: Frank Kent.

By 1940 the depot was gone, and the Brown building had a new neighbor: Frank Kent.

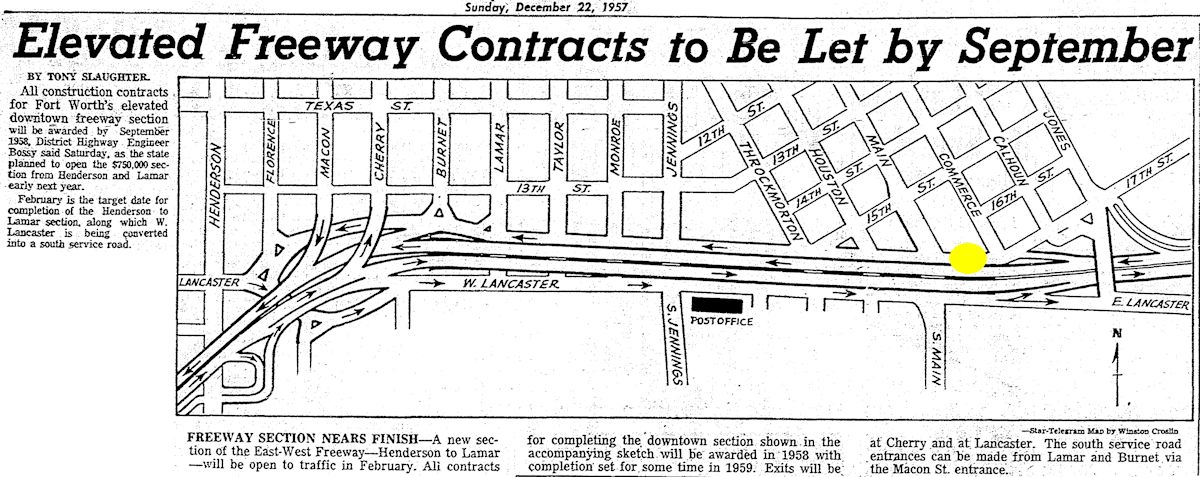

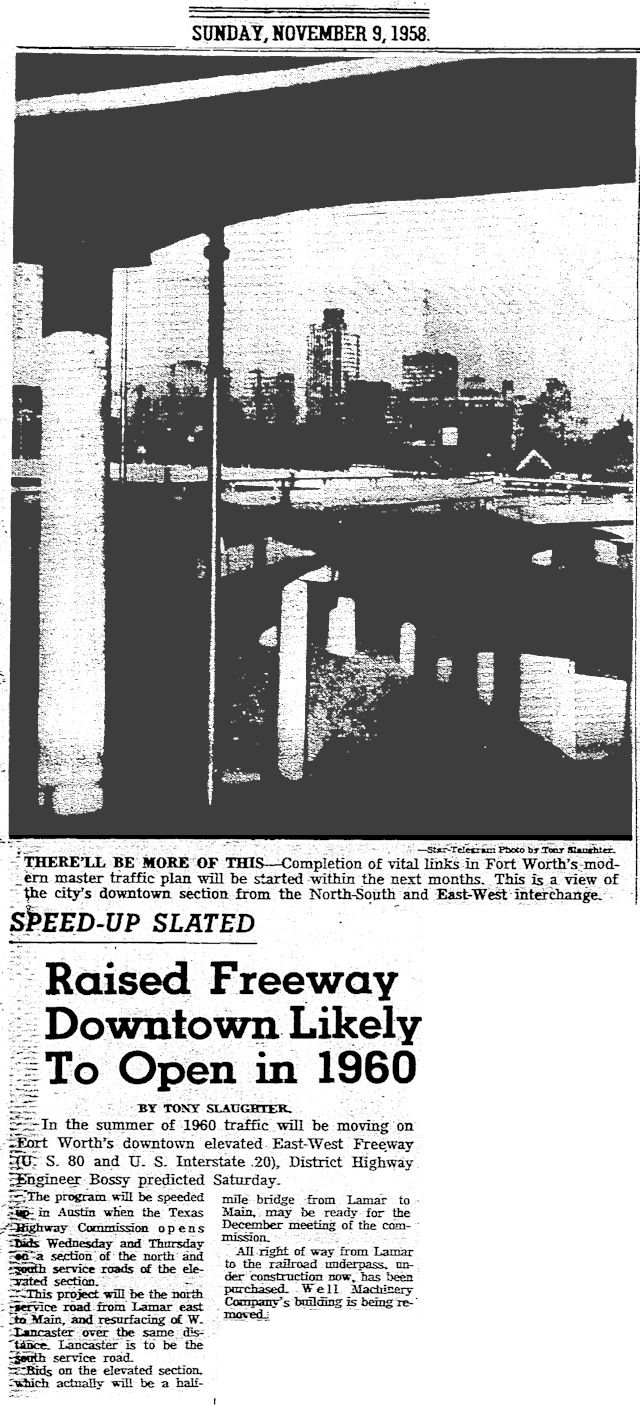

By the late 1950s the Brown building was doomed by an invention that had not existed when the building was new in 1886: the automobile. The East-West Freeway (Interstate 30) was being built through south downtown. Brown’s building would be demolished to make way for the elevated section over Lancaster Avenue.

By the late 1950s the Brown building was doomed by an invention that had not existed when the building was new in 1886: the automobile. The East-West Freeway (Interstate 30) was being built through south downtown. Brown’s building would be demolished to make way for the elevated section over Lancaster Avenue.

After thirty years in the Brown building, Well Machinery & Supply Company held a removal sale and moved to a new location: 2901 Shotts Street.

After thirty years in the Brown building, Well Machinery & Supply Company held a removal sale and moved to a new location: 2901 Shotts Street.

In November 1958 the Star-Telegram reported, with no sense of history, “Well Machinery Company’s building is being removed.”

In November 1958 the Star-Telegram reported, with no sense of history, “Well Machinery Company’s building is being removed.”

Fast-forward five years. In 1963 Well Machinery & Supply Company, final occupant of the building built in 1886 by the man from Dundee, Scotland, was bought by our third connection: George Levitan. Levitan, a white man, also was publisher of Sepia magazine. In 1959 Levitan had encouraged another white man, writer John Howard Griffin of Mansfield, to darken his skin and spend six weeks living as a black man traveling across the segregated South. In 1960 Griffin described his experiences in the serial “Journey into Shame” in Levitan’s Sepia magazine. The account was published as a book entitled Black Like Me.

Fast-forward five years. In 1963 Well Machinery & Supply Company, final occupant of the building built in 1886 by the man from Dundee, Scotland, was bought by our third connection: George Levitan. Levitan, a white man, also was publisher of Sepia magazine. In 1959 Levitan had encouraged another white man, writer John Howard Griffin of Mansfield, to darken his skin and spend six weeks living as a black man traveling across the segregated South. In 1960 Griffin described his experiences in the serial “Journey into Shame” in Levitan’s Sepia magazine. The account was published as a book entitled Black Like Me.

Joseph H. Brown’s building stood just south of today’s Water Gardens Place.

Joseph H. Brown’s building stood just south of today’s Water Gardens Place.

Today the nondescript building at 2901 Shotts Street is owned by the Fort Worth school district.

Although the stately Joseph H. Brown building has been gone sixty years now, the Gazette’s prediction in 1886 was accurate: For seventy-two years Brown’s building stood as “a monument to his commercial greatness” and as a reminder of life in early Fort Worth.

Is there any blood relation, even if distant, between John Burnett Collins and Samuel Burk Burnett?

Anne, so far I have found none. Nothing in J. Burnett’s obit or will to indicate a tie. Both men from Missouri but not especially close geographically. J. Burnett was a graduate of Yale.